Location: Montery Bay, CA

THIS ESSAY IS TAKEN FROM A KEYNOTE given at a WEAD conference in 2001 following 9/11 and updated now, a decade later.

I. AFFIRMING AND RENEWING VALUES

WITHIN OUR WORK AS ARTISTS AND ACTIVISTS it seems even more critical to affirm and renew our values at this time of global disasters and wars and a decade after 9/11. In the wake of the World Trade tragedy we were left with a sense of turmoil, fear, impending destruction, and an earth in chaos. In these ten years since that fateful day we have seen a greater and expanding sense of this turmoil in global wars and displacements, the Katrina floods, two devastating Tsunamis in Asia, earthquakes in Haiti and Chile, and the oil-rig disaster of Deepwater/Horizon. All of this, as well as the continuing effects of global warming, brings us as artists concerned with environmental and cultural health to an even deeper concern and responsibility. We are perhaps at a turning point in which we must evaluate the many complex ways we can move our art in service of our earth.

II. RECLAIMING PRACTICES

AT TIMES LIKE THESE WE MUST RECALL FOR ourselves what draws us to our work, reclaim the feminist and multicultural practices related to our values on the environment.

As artists and activists in the shadow of the millennium we are creating a new art through metaphor, symbolism and complex analysis which links our understanding of both nature and culture in this artistic response.

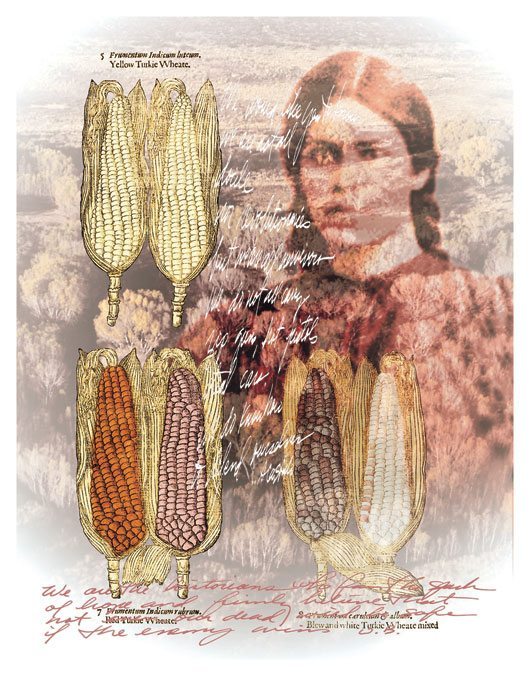

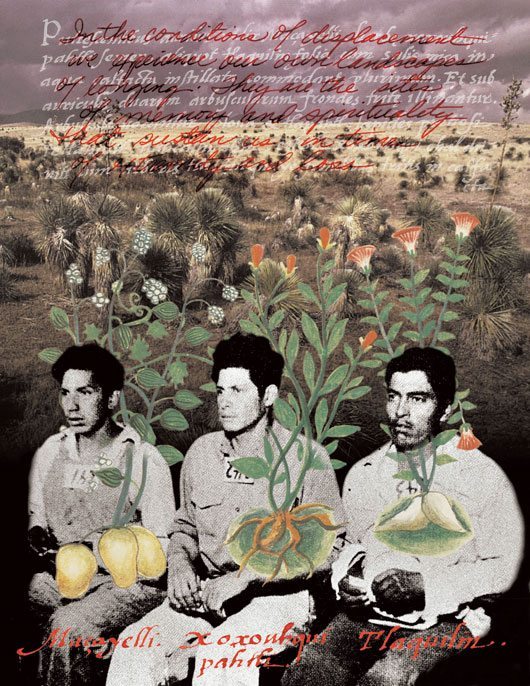

Our struggle for balance begins with our own indigenous history of peoples of the Americas. Even the ancient Mesoamericans knew that our life on this earth was brief – like the spring grass and the flowers we bud, blossom, dry up and blow away. We are living here as the flowers in nature’s cycle.

We are reminded of the poignant words of Chief Seattle in his letter to the Whiteman :

‘What will happen when the buffalo are all slaughtered? The wild horses tamed? What will happen when the secret corners of the forest are heavy with the scent of many men and the view of the ripe hills is blotted by talking wires? Where will the thicket be? Gone! And what is it to say goodbye to the swift pony and the hunt? The end of living and the beginning of survival. When the last Redman has vanished with his wilderness and his memory is only the shadow of a cloud moving across the prairie, will these shores and forests still be there? Will there be any spirit of my people left?’

His words remind us that relations in the world are not just between humans and nature but humans one to another reflects our ecology together on this planet.

The affects of poverty and economics and the vulnerability of our communities are evident when we see toxic dump sites concentrated in communities of color. Artistic collectives like ADOBE LA ( Artists, Designers on the Border Edge of Los Angles) have documented these sites in maps hidden in public art works. We see where families and children suffer the consequences of illnesses, global struggles for clean water and the basic rights of farm workers to safe labor conditions free from pesticides. We must be vigilant against the false polarities of immigration and conservation in an era of dwindling resources.

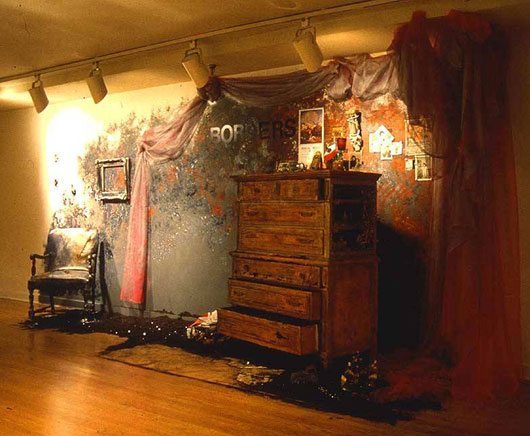

In my own work the landscape is referenced to reveal our histories and our conflicts. My installations for over the last two decades have addressed nature through themes of spirituality, stewardship, and balance. In many of my pieces nature and landscape are metaphors for the balance of life, healing and death in family, and labor narratives.

We must bring to the forefront the practices that enable artists to do social justice work. It is critical that we make linkages between the peril of the earth and the role of the artist and their practices of reflection, analysis, or activism. Our art forms can bring us closer to nature and healing and inspire us to revision the world. Art can also be a tool for understanding the ecological practices needed and the place of artists collaborating in this endeavor.

III. PUBLIC SPACES

ARTISTS SHARE PUBLIC SPACE AND LANDSCAPE in the fullness of both bio-diversity and cultural diversity.

In cities across the country we are involved in the rethinking of public life, a more equitable access to space, and inclusive public art that places the artist at the boundary between the public and the private. In this artistic activism we use both analysis and practice. This has become more clear to me in the years that I worked with my colleagues founding a program of Visual and Public Art at California State University at Monterey Bay in 1997- present.

The university was created out of the old Fort Ord Military Base and offered us a chance to create the 21st campus in the CSU system for a 21st century. It is situated on the Monterey Peninsula near to the affluent cities of Monterey, Carmel and Pacific Grove. Yet the university is all connected to nearby Salinas, Watsonville and Seaside, all communities of color. When I first began developing community contacts in our region for our program I often drove from the university to Salinas traveling down Blanco Road (the white road ) watching from my car window the farm workers bent over the strawberry fields often seven days a week. When I am on Blanco road, the white road, I think about how people live and the economies of space.

Some classes of people live their public lives privately because of gated communities, guards, servants and on-line services. Where other classes of people must live their private lives in public because we have not provided adequate recreational space, affordable housing and healthcare. It is truly a geography of inequity in our region and not unlike the geographies of inequity that mark the world.

The role of the artist in this environment is critical. We are redefining the artist not as lonely hero/genius, but rather as a social architect, as cultural citizen concerned with the communities rights to identity and space, and as a mediator and problem solver at the edges of shifting and permeable borders between the private and the public.

IV. PRACTICING COMMUNITY ART

MANY OF US HAVE BEEN DRAWN TO THE WORK in community in hopes of a creating a transformative practice that is inherently social and spiritual at its core. Nature and landscape bear the signs of our abuse, they stand as a witness to our histories of struggle. The terrain we enter is like our mother earth and many of us have cultivated feminist and multicultural strategies of inclusion in making art with people not simply for people.

These practices form an artistic pedagogy that engages a reciprocal teaching and learning. Our communities bring their funds of knowledge to the collaborative process of design and implementation. If we are truly reciprocal we are making work that affirms the assets our communities and brings a greater understanding across our differences.

As artists our practices bring us into relation with individuals, families, communities, institutions and civic bureaucracies in the development and completion of a project. Often these encounters are difficult and require tenacity, a spirit of collaboration and a passionate resiliency. I am reminded of the case of Patricia Johanson works, Endangered Garden, SF Garter Snake, Butterfly Marsh and Barrier spit, 1988 at the Sunnydale pump station and holding tank for water and sewage plant.

Under the San Francisco art Commission I inherited oversight, as a commissioner, in the late 80’s for Ms. Johanson’s project. Through the ten-year process in which the cultural affairs department bifurcated the sewage plant from the garden we came to understand that the garden had only been used to disguise an unwanted and unpleasant sewage plant. Once it was approved the public art project was separated and lingered and diminished in its scope from the once brilliant ecological vision to a much smaller and little appreciated garden. With the support of project manger Jill Manton Ms. Johanson was able to realize some of the original project but only the artist’s tenacity over a decade brought this project to near completion. This is only one of many stories of bureaucracy and artistic resiliency.

There are so many legendary artists who work also as collaborators and in practices of analysis and activism. Artists like examples like Mel Chin, the Harrisons and Reiko Goto and Tim Collins at 9 Mile Run are but a few. Their practices suggest to us the skills that we must teach to our students so that they can bring together bio diversity and cultural diversity. Our challenge is to prepare younger artists that these two aspects of social justice are not separate but can be brought together.

Many of you have done the work on the ground to transform the communities you live and work in. We are now trying to codify the ways in which we work to pass on these practices to emerging artists who will carry on this work. This legacy is at the heart of what we are trying to do at Visual and Public Art department at California State University at Monterey Bay. This program was originally conceptualized by Judith Baca, Suzanne Lacy, ,Johanna Poethig, Stephanie Johnson and myself. It is a program of studio arts, theory and education models committed to community practice that focuses through skills of :

Research and Analysis,

Self and Identity,

Community,

Collaboration and planning,

Production,

Revision,

Distribution.

Our work is founded on the university’s vision of ethics, social justice, global and environmental responsibility and service. In particular our Service Learning model links service, analysis, compassion, justice and reflection.

We work to integrate these skills as an ongoing set of practices within a critical approach to our relationship to public space. Our spatial theories are driven by work by theorists such as Edward Soja, Michel Dear, Jennifer Wolch and Henry Lefebre.

We know that all space is at all times social, physical, and geographic and that no space is empty when we reach it, the memories of those who walked before us are there.

We know that space can be inclusive or exclusive and that the construction of space is ongoing as a social, spiritual, political and economic practice.

Edward Soja’s theories on social and public space and histories of the disenfranchised have been very critical to understanding the issue of nature and landscape.

‘ We see how space can be made to hide consequences from us, how relations of power and discipline are inscribed into an apparent innocent spatiality of social life, how human geographies became filled with politics and ideology’ [i]

In our age the greatest social public space is the Internet with its global power. Activists around the world give us hope as examples of the interconnectedness of world economies, the natural world, labor, cultural right are brought to bear through the worldwide web.

We are in a time of new models, integrating commitments, practices, values and beliefs. Art is not simply a compassionate and didactic response but a complex layering of issues, metaphors and materiality and spiritual transformation.

We must ask ourselves

- How can we develop the natural environment to foster cultural and social connections?

- How can we strengthen the relationship of landscape to public space?

V. CONCLUSION

ALTHOUGH I SITUATE MYSELF IN THE WORK OF reflection and the spiritual practice toward nature and healing, I see the work of all of the artists who attend to our earth as having a spiritual center. I will end by quoting a passage I wrote in regard to Chicano spirituality in hopes that our global condition now can reveal the spirituality at the heart to our new work for earth.

‘To understand the art work that is inspired by sacred sources it is important to establish the concept of memory. The relationship of memory to history is the connection between the past and the present, the old and the new. For the Chicana/o community there is no absence of memory, rather a memory of absence constructed from the losses endured in the destructive experience of colonialism and its aftermath. This redemptive memory heals the wounds of the past. Memory can be seen as a political strategy in work that reclaims history for the community. In a sense the art making inspired by the remembrances of the dead, the acts of healing and the reflections of the sacred can be seen as a politicizing spirituality.’[ii]

Our work as artists bears the mark of a politicizing spirituality as we hold for our mother earth a redemptive memory in this time of global chaos and loss.

[ii] Amalia Mesa-Bains in ImagenesE Historia/Images and Histories: Chicana Altar-Inspired Art, Ed, By Constance Cortez, Tufts University, 2000,