Location: Navajo Nation // Prescott and Flagstaff, Arizona.

I. DANGEROUS BOUNDARIES

MINNIE CHASING HER SHEEP AND GOATS. Photograph/ Wheat paste poster, building. jetsonorama (1)

UNLIKE MANY IN OUR beleaguered time, I have the privilege of spending whole days outside – I don’t take this opportunity for joy lightly, and thus have paid special attention to the smaller birds. One Sunday, at 7000 feet, in a fir forest that I’m sure many would not associate with Arizona, I gratefully received the gift of seeing a pair of Olive Warblers. They appeared suddenly in the light of approaching evening; his feathered hood an eye popping cadmium orange, hers a more subdued yellow green – each sporting a diminutive bandit mask and a double row of sprightly white wing bars. Together they foraged at the outermost branch tips 50 feet above us, then twirled lightly and in a couple of strong wingbeats disappeared beyond my perception.

There is nothing like a migrating bird to remind you that distance is surmountable. We see the Olive Warbler at the northern edge of its range; it breeds up here in the mountains of the American Southwest, but is a year-round resident of the highland spine that extends the length of Mexico. An insect eater during our well documented insect apocalypse, it is vulnerable to pesticide use on both sides of the border. If you study the range maps in a bird field guide, the idea of political boundaries – those self-importantly drawn delineations – becomes both absurd and dangerous.

And what about the human boundaries that keep us justifying and accepting all sorts of prejudices, brutalities, and unjust policies?

II. BITTER ROOTS

DAVONA BLACKHORSE Speaking with the author near Dook’o’oosÅ‚ÃÃd, the Diné sacred mountain of the West, known in English as the San Francisco Peaks. Klee Benally. (2)

‘Historical trauma is not just a buzz word. Intergenerational trauma is not just a buzz word. It’s a real thing and it can destroy you.’ Davona Blackhorse.

Davona Blackhorse is sitting under a Ponderosa pine with Dook’o’oosÅ‚ÃÃd, the sacred mountain of the West just over her shoulder. But her stories flow to the north and east across the wide miles of Dinétah, to her grandmother’s Hogan on Big Mountain where her umbilical cord is buried.

These are stories of art and resilience, of trauma and nature and healing. I will share some of them here, but first I need to begin at a different beginning.

In the summer of 1864, just as the fruit was ripening, a captain in Kit Carson’s army cut down 4100 peach trees in Canyon de Chelly, a last stronghold of the Diné. It was one more brutalization in a wide ranging scorched earth campaign; Carson’s men destroyed fields, torched houses, slaughtered livestock, ruined water sources, and smashed every pot or vessel that could carry food.

Throughout 1864 and 1865 the American army marched nearly 9000 desperate, starving, traumatized people hundreds of miles from their homeland – the place between sacred mountains where healing ceremonies of generations affirmed the way of balance and beauty. In the internment camp at Bosque Redondo, they faced famine, illness, and terrible thirst; soldiers raped women in exchange for rations. They shot men who tried to protect their wives and daughters. Syphilis raged. One in four incarcerated Diné did not survive. It was all a strategy – force Indians to adopt White American values. And the other motivation: Carson’s military commander was certain that there must be gold somewhere out there on that land.

In 1868 those who did survive walked the hundreds of miles back home. In the face of intense pressure to move yet further east to Oklahoma Territory, elected men and strong women leaders stood firm on going back to the land they loved. The 20 pages of signed concessions included sending children to U.S. schools, allowing a railroad through their land, and an agreement that the authority of the United States would thenceforth limit tribal sovereignty. But the people could return.

Then in 1934 the Indian Reorganization act further eroded tribal autonomy across the U.S. by supplanting indigenous forms of government with tribal councils. All contract negotiations for mineral and timber leases, water rights, and land transfers required approval of the BIA representative. On the Navajo Nation, the process started earlier. In 1923, a council of elders refused most oil and gas lease proposals. They were summarily removed and replaced with government-selected, lease-friendly individuals.

Thus is ushered in the era of resource colonialism on the Navajo Nation. The American government, acting as agent of private industry, enacts agreement after agreement to systematically strip those materials valuable to industrialized culture – and what it considers the wealth of Dinétah: the oil, the coal, the uranium.

In the 1960s Peabody Western Coal Company executed lease agreements with the Navajo and Hopi tribal governments that permitted the extraction of an average of 14 million tons of coal per year. They wanted access to an additional estimated 20 billion tons of coal beneath the Joint Use Area – land held in common by the two tribes. Study, if you will, the decades-long legal machinations. But this is what finally happened: together two coal mines on Black Mesa (Big Mountain) ended up as one of the largest strip mining operations in the United States. Every year for 34 years, it consumed 1.3 billion gallons of pristine ground water from the Navajo Aquifer for coal slurry transportation.

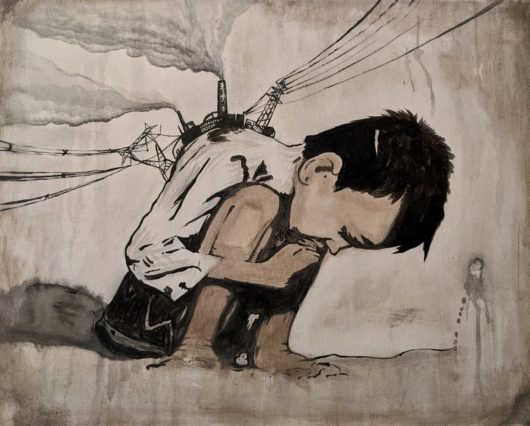

CONSUME, Acrylic on Canvas, 20′ x 16′. Klee Benally (3)

This also happened: the federal government instigated a program to remove about 100 Hopi people and 10,000 to 30,000 Navajos from their homes. And at the same time, established a building freeze on 1.5 million acres of Navajo land so that fixing roofs, or repairing corrals, restoring water systems, building schools or roads became criminal acts. Under the associated livestock reduction, families with a traditional pastoral economy faced terrible hardship – mired in the impossibly stacked odds of resistance, arrest, anxiety, and hunger; all on top of illness from a sorrow-colored curtain in the once crystalline air.

As part of his work documenting the stories of Navajo elders and advocating for cultural literacy in his community, Malcolm Benally went up to Big Mountain to create an oral history of what people were experiencing. Roberta Blackgoat described life after coal mining began, ‘It is smog on the horizons. Her breath, her warmth, is polluted now and she is angry when Navajos talk of their sickness. The coal dust in winter blows in to blanket the land like a fog down the canyons. It is very painful to the lungs when you catch a cold. The symptoms go away slowly when dry coal dust blows in from strip mining.’

Davona describes waves of terrible worry, rooted in fear for the traditional reciprocal relationship with a nourishing earth, ‘Big Mountain is important to most of my family because that is where all our umbilical cords are buried, in our sheep corral there. So my grandma would always tell us – you always have to return back to your home and this is your mother. So I think when the coal mining happened, it changed our way of thinking, like, ‘Wow, what will happen to this sheep corral where our umbilical cords are buried? What’s going to happen to our cornfield?’ All of a sudden everyone had this sense of fear . The grazing permit person is coming! And we started living more in fear. And then they put the fence, the boundary, the relocation fence through our cornfield and then it went through behind our house. They put the fence there so now it’s like we can’t even go across.’

III. URANIUM MINING, SLOW-MOTION CATASTROPHE

FEVER FOR URANIUM – Yellow Dirt – opened a new era of environmental racism that played out with tragic consequences. It ignited in 1944 as the United States Government developed bombs that would obliterate Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Through 1986, mines on Navajo land supplied nearly 30 million tons of uranium to feed a voracious Cold War appetite. There are still over 520 abandoned mines on Navajo Nation – some within sight of communities – thousands more on its borders. In this land where the phrase ‘Water is Life’ is no remote platitude, the Environmental Protection Agency has closed 22 wells due to radioactive contamination.

LAND NEAR CAMERON ARIZONA, Photograph. Dana Oswald (4)

Health effects on the people? Ongoing lung cancer from breathing radioactive particles, bone cancer, impaired kidney function, breast cancer, auto immune diseases. Uranium measurements in the urine of some babies born in Navajo country actually increase during the first year of life.

Roberta Blackgoat told Malcolm Benally, ‘The coal they strip mine is the Earth’s liver. The earth’s internal organs are dug up. Mother earth must sit down. The uranium they dug up for energy was her lungs. Her heart and her organs are dug up because of greed.’

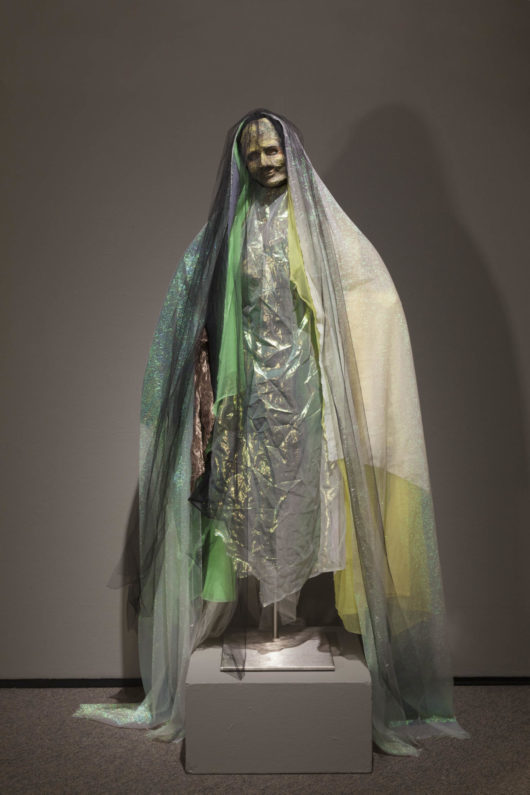

RADON DAUGHTER, Mask and Textiles, 36′ x 20′ x 70′. Pash Galbavy (5)

IV. GIVING FORM TO SILENCE

And there was a silence in the dust as it hung in the air inside the mines and in the mills.

And a silence in the cool water the miners drank as it dripped down the sandstone walls of the shafts.

And there was a silence by the scientists and the medical teams who monitored the miners,

And for economic reasons, there was a silence by the Navajo political leaders

And the winds continue to blow across the land and the summer rains continue to wash the uranium laden dust, collecting in the watering holes used for thirsty sheep – flesh into food – and in the flora used for medicinal herbs and dyes for wool blankets.

It is invisible. It has no odor. It is silent. It enters bodies as they breathe the air, as they drink the water, as they eat the mutton, as they sleep on the sheepskins in their hogans.

And what is the responsibility of the artist? To give form to this silence, to become visual storytellers to the silent history of a people, their trauma, their hope.

–Shawn Skabelund,Curatorial Statement, Hope and Trauma in a Poisoned Land, exhibition at the Coconino Center for the Arts, Flagstaff, Arizona (Sponsored by the Flagstaff Arts Council and the National Endowment for the Arts).

While an undergraduate at Northern Arizona University in Flagstaff, Davona got to talking with one of her professors, Ann Collier, about how, in Navajo culture, the weaving arts bring healing. They consulted with curator and installation artist, Shawn Skabelund and together planned a series of workshops for artists exploring the effects of uranium mining on Navajo land and people.

Hope & Trauma in a Poisoned Land was a partnership between the Cameron Chapter House of the Navajo Nation, the Flagstaff Arts Council, University of New Mexico Community Environmental Health Program, and Northern Arizona University. For four days, artists walked on the landscape where uranium mining and contamination occurred and listened and shared stories of life where the yellow dirt and the silence had damaged so many.

As a young girl riding in a hot car across the wide landscape of cinder cones and distant mesas, Viki Blackgoat was amazed to pull off at a shimmering water hole. ‘After some uncertainty about directions to the water tank,’ she remembers, ‘we pulled up to a large pile of earth that encircled a deep hole. I looked back on the lowest part of the lip. I could see that there was an earthen ramp leading to a pool of water. The water was still partly in shadow. But the portion that received light was an odd green hue, yet clear. The light lazily played on its surface. I felt strangely fearful without reason. Guys were soon dashing and jumping into the pool, waving, splashing, swimming. Shouts of delight, laughter, and calls for me to join in the fun bounced off the walls. Instead, I sat in the driver’s seat where there was some shade and relief from the desert heat. Years later I realized that the tank we visited had one day been a catchment or a holding tank for a uranium processing operation. There was no fencing, no signage, nothing to warn of risk or danger.’

Davona describes the miners.

‘I had a photo and there was a bunch of men in there and they were looking very healthy, young and smiling and they were miners and that was what our men looked like. They were very honorable, they were very traditional and even though that wasn’t really our way of living, they were going to go into those mines and they were going to provide for their families and there was a lot of loyalty there and a lot of dedication to family. And now a lot of our men are wounded by this. There is a generation that has been lost of strong leaders that would teach our cultural teachings and teach our young men how to be warriors.’

These men averaged cumulative radiation exposures that were about forty-four times higher than the levels at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. There was no information provided and no protection offered.

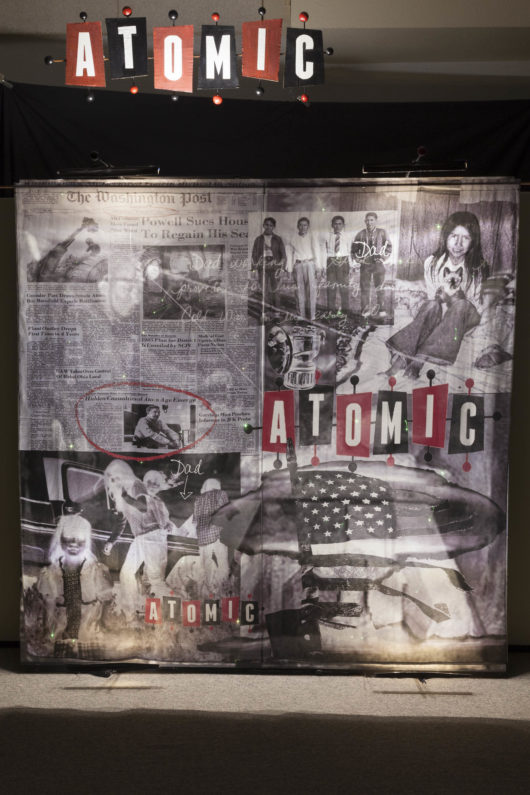

Chip Thomas is a physician at a clinic on the Navajo Nation. He asked a co-worker whose father worked in a 60’s era uranium mine and died of a uranium related cancer if she would share memorabilia from those days. She provided photographs and shared stories of her dad. Her mother also died of a uranium related cancer and her older brother also suffers from a uranium related cancer. Chips’ installation in the Hope and Trauma exhibit, Atomic (r) Age is both poignant homage and indictment.

ATOMIC (R)AGE, Installation at Coconino Center for the Arts, Hope and Trauma in a Poisoned Land. 99′ x 21′ x 98′ jetsonorama (6)

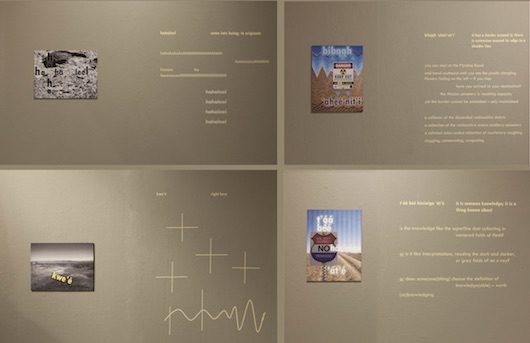

As a poet and multimedia artist, Esther Belin’s four panel piece relates the experience of an indigenous person living in a beloved and poisoned homeland.

LOSS OF SPHINCTER. Photographic Prints and Poems, Four prints, 21′ x 16′ each, installation at Coconino Center for the Arts, Hope and Trauma in a Poisoned Land, Esther Belin. (7)

Venaya Yazzie is an indigenous artist, poet, photographer, and cultural educator. Her teaching focuses particularly on perpetuating the ways of the tribal matriarchy. For Summoning Hózhó, Perpetuating Beautyway, Slaying Monsters, she placed the matrilineal tools that bring beauty and balance; a loom, a woven rug – together with elements that evoke costs of nuclear pollution.

SUMMONING HÓZHÓ, PERPETUATING BEAUTYWAY, SLAYING MONSTERS, 64’x 34′ x 55′. Venaya Yazzie (8)

For my installation I decided to use dust masks, the absolute minimum protection that could have been offered to the miners – but wasn’t. Yellow Dirt Testimony, a Promise in Many Parts, was an 18-foot mushroom cloud constructed from dust masks sent to me by over 300 people from Hawaii to Florida. Responding to information I sent, they decorated the masks with heartfelt expressions and made the commitment to not let something like this happen again.

YELLOW DIRT TESTIMONY: A PROMISE IN MANY PARTS, gallery view. Installation at Coconino Center for the Arts, Hope and Trauma in a Poisoned Land. Edie Dillon (9)

V. BITTER FRUIT

BY LATE APRIL OF 2020, the Navajo Nation had the third highest Covid-19 rate in the United States. The contributing realities – lack of running water and electricity, hunger, high rates of covid-worsening conditions like diabetes, immune disorders, compromised lung function, and obesity – are often reported without context. The dominant culture’s response to poverty and illness is typically a lather of pity. But pity depends on belief in separation. An other – too often seen as a victim, or worse, creator, of their circumstances – is undergoing misfortune. The self-fulfilling cycle of ‘poverty porn’ props up the systems that caused problems in the first place.

Electrical lines run all across the flowing landscape of Dinétah, but the power goes to Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Phoenix.

Before the strip mines and slurry line, artesian springs rose from the Navajo Aquifer like a blessing. Now families on Black Mesa haul 50 gallon tanks to public, taxed wells and must wait hours in line in the drier seasons.

For 40 years, the Navajo Generating Station’s three smokestacks fouled the sparkling desert air, spewing tons of carbon dioxide, carcinogens, and neurotoxins over the land. An April 2020 Harvard study established a link between particulates released by power plants and significant increase in the death rate from Covid-19.

NÃÅCH’I, AIR; IINÃ, LIFE; KÉYAH, EARTH; TÓ, WATER, Photographic prints, 10′ x 14′ each. Amy Martin (10)

The Diné Policy Institute studied the Navajo food desert, concluding that the ‘current food system contributes to the epidemic levels of nutritionally-related diseases and disintegration of DineÌ lifeways and K’eÌ (the ancient system of kinship observed between DineÌ people and all living things in existence.) But, as activist and artists Klee Benally observes, ‘Until colonization, and the systemic destruction of indigenous lifeways, Dinétah wasn’t a food desert.’

At Big Mountain when Davona was a child,

We started to realize that a lot of what the land was giving us was our wealth. It was providing a way of life for us and when that was taken away we started depending more on foods from the store, from the grocery store. Processed food, commodity foods, things that would last. We didn’t have access to our cornfield anymore and that’s where we got our antioxidants. And when you replace that with a can of peaches that has preservatives and all these other toxins in there. So it’s hard to heal when you are dealing with all this toxic stress. It starts a wear and tear on your body.

VI. MANY WAYS TO LIVE DOWNWIND

WHITE PEOPLE LIVING IN TOWNS near nuclear tests are often described as ‘Downwinders.’ There are other ways to end up downwind; the cancers from exposure while mining, the uranium polluted water that children swim in, the dust that blows across homes from abandoned mines. But an emotional and spiritual ‘downwind’ metastasizes illness in the soul if we block our natural sense of kinship and accept as normal the brutal harm we do to the earth and her peoples. Roberta Blackgoat, speaking from Big Mountain, said, ‘The people say the uranium can dry up your heart.’

Uranium mining is no longer allowed on the Navajo Nation. But there are new mines proposed around its edges. Of particular concern is the Pinyon Plain Mine (formerly Canyon Uranium Mine) just 10 miles south of Grand Canyon, near sacred Red Mesa. The material from this mine would be hauled over the Navajo Nation on Federal highways over which the locals have no jurisdiction.

VII. SUMMONING HÓZHÓ

‘In life we’re all trying to find balance. We’re all trying to balance ourselves.’ Davona Blackhorse

So how do we find our way back to kinship, and beauty, and balance? As Covid-19 swept across the Navajo and Hopi nations like the hot winds of June, groups formed throughout the area to coordinate emergency relief. Klee Benally, organizing Covid-19 response through KinÅ‚ani Mutual Aid, points out that ‘more than 30 groups are coordinating emergency relief in various forms of direct actions throughout our communities. We are not victims, but survivors,’ he says, ‘who continue to resist and fight for Mother Earth and our future generations.‘

Unlike charity, mutual aid operates without the hierarchical leadership or philanthropic funding that feeds most nonprofits. Rather than fixing symptoms, it is aimed at the illnesses within our society’s core structures. The motivation arises from a belief that we’re all in this together; that solidarity and reciprocity, rather than self-interested competition are the essential driving forces of evolution.

Klee Benally describes mutual aid this way: ‘Basically any time individuals and groups in our communities have taken direct action and supported others, not for their own self-interests but out of love for their people, this is what we call ‘mutual aid.” He adds that mutual aid, rooted in K’eÌ, ‘does not exclude our non-human relatives or the land. On Dinétah, this looks like a small crew coordinating their relatives or friends to chop wood and distribute to elders. It looks like traditional medicine herbal clinics or sexual health supply distribution. It looks like community water hauling efforts or large scale supply runs to ensure elders have enough to make it through harsh winters.’

GREEN ROOM AT DAWN. Photographs, wheat paste posters, building, corn plant. jetsonorama (11)

The Diné Policy Institute recommended, ‘revitalizing traditional food knowledge through the reestablishment of a self-sufficient food system for the Diné people.’ Mutual aid also looks like people organizing to save heirloom seeds and share knowledge of wild edible and medicinal plants.

After the devastating loss of the grandmother who raised her, Venaya Yazzie co-curated an exhibit, ‘Resilient Matriarchy: Indigenous Women’s Art in Community,’ hosted by Open Doors Arts in Action, a project of the Episcopal Church of the Epiphany in Flagstaff. ‘I think for a lot of these artists,’ she says, ‘they’re just reaching back to their roots of who they are as Indigenous women from their tribes that they’re coming from and saying, ‘Even though this hard stuff’s going on, we’ll still endure and we’ll still continue what we do. I just hope other people will see that and then say, ‘Well, in my own life, how can I continue and keep trying to stay healthy and have my community healthy, have my family healthy?’ And really looking at art as a way of healing, a mechanism.’ To help grow resilience on the Navajo Nation, the exhibit linked to organizations working with indigenous women and communities.

BIZHI’BA TREKKING THROUGH ANCESTRAL GRIEF, OFFERING MIGRATION AS HEALING lV.Digital Photograph. Venaya Yazzie (12)

VIII. IMPERFECT KARMA

IT BECAME OBVIOUS THAT the best use for Yellow Dirt Testimony: A Promise in Many Parts was to disassemble it and (re) repurpose the masks.

Each mask needed elastic or ties reattached. I sought help and, again, the response was hands-on, and heart felt: a friend from childhood sent 200 yards of elastic, another stayed up to 3 am sewing on ties. My daughter’s first grade teacher met me at my porch to drop off finished masks, 50 and a hundred at a time.

Some of the thousands of lightly painted masks (re)repurposed from YELLOW DIRT TESTIMONY, A PROMISE IN MANY PARTS. Thomas Fleischner. (13)

The end of the story for this sculpture is, sadly, fitting. My brother called it “Imperfect Karma.” And it is that, but it is also the logical and tragic conclusion of decades-long enforcement of the perceived boundaries between people that have allowed one group of people to treat another as expendable.

The gestures of help to transform the masks first into art and then back into usable protection may seem small, but cumulatively they are significant, arising from a feeling of kinship and connection. A virus, like radiation, knows no boundaries. But all the people helping also refused to accept the old separations.

Within the week of delivering the first thousand masks to Flagstaff, my son and his girlfriend drove to Poston, Arizona, site of the concentration camp where 17,000 people of Japanese descent were incarcerated during World War ll. It was a pilgrimage of sorts for her; her maternal grandfather was imprisoned there. They brought a mask from the sculpture decorated with paper cranes folded in Japan and carried to Arizona by Hibakusha, survivors of the bombing of Hiroshima, to commemorate connections over time and space with the sorrow of Navajo uranium mining widows. Our boundaries can seem recalcitrant and solid but in reality they are as illusory and permeable as we choose. The connections between us are as real as the flight line from one mountaintop to another.

In Viki Blackgoat’s garden, far in time and space from the ghoulish green swimming hole, you can almost believe that the world will be ok. Here at the edge of the pines in the shadow of the sacred peaks, we offer a word of hope with each scoop of compost. We water the tiny cabbage and kale by hand. Clear, good, nourishing water for each slender set of roots.

VIKI BLACKGOAT WATERING, Edie Dillon. (14)

Davona Blackhorse speaks with determination of her own path of healing. How she traverses between memories of days speaking to the wind at the Big Mountain sheep camp and negotiating the vicissitudes of a PhD committee, and why. ‘For me one of the main reasons I wanted to take the route I did was because it wasn’t always so easy for me dealing with trauma. And understanding how debilitating that is. And the best way of healing is to do the work that I’m doing, is to help others.

Davona reflects on the Hope and Trauma in a Poisoned Land exhibit’s value,

And that’s what Hope and Trauma was, too, was to show the community that we were going to advocate for them – that we were going to do this project – that we weren’t going to do a ‘study’ on them, we were going to make space for them to tell their stories and turn that into a visual, into art – something that’s healing. When you see the world through a traumatized lens it distorts the way you see things. So being able to see that hope and that spiritual part of it in another light, it was healing. The system is set up to teach one way of thinking and one mindset and one history where we honor our colonizers, where we honor the people who perpetuated violence against us and then we’ve lost who our heroes were, who our warriors were and we are honoring the wrong people.

Art breaks the silences, erases separation. It is a language that crosses the boundaries we otherwise might accept. Artists help us see the realities of our dilemma, challenge accepted ways of thinking, provide vocabularies for healing, and create the vision for our shared future. All of our future: the five fingered ones and the four leggeds, and the ones that fly.

I am imagining that at this moment somewhere high over the Sonoran desert a small bird with a tiny bandit mask is winging his determined way over a 27 foot steel barrier. His belly is full of Mexican bugs and he will alight at evening on a springing branch tip. He’ll send a song across the fir-scented air and a sweetheart dressed in yellow will answer. I hold the vision of a time when humans will treat distance with his same resolute disregard. We will have realized that the separations that allowed us to believe one people or one place less valuable than another were constructed from old ideas and passing illusions – a peculiar line someone once thought was important, like a border drawn in fading ink on an antique map, insignificant and forgotten, far below our high and winging dreams.

A version of this article was published in the Natural History Institute Real Ground Journal in May, 2020.

PHOTO CREDITS

- Minnie Chasing Her Sheep and Goats. Photograph/ Wheat paste poster, building. ‘I’ve heard from members of the community that they feel a sense of pride when they see the images and appreciate that the images give people passing through the area (located in a tourist area between Monument Valley and the Grand Canyon), a sense of who is there. One of my motivations for placing images along the roadside is to reflect some of the beauty of the community back to them.’ Chip Thomas

- Davona Blackhorse speaking with the author near Dook’o’oosÅ‚ÃÃd, the Diné sacred mountain of the West, known in English as the San Francisco Peaks. Klee Benally.

- Consume, Acrylic on Canvas, 20′ x 16′. Klee Benally.

- Land Near Cameron, Arizona. The beauty of the landscape belies the menace of the more than 100 abandoned uranium mines (AUMs) in this area. There are 525 abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo Nation (Dinétah). Dana Oswald.

- Radon Daughter, Mask and Textiles, 36′ x 20′ x 70′ Installation at Coconino Center for the Arts, Hope and Trauma in a Poisoned Land. Pash uses masks to animate inner parts of the psyche that are reflected in the larger world stage. In her artist statement Pash explains, ‘Radon is a toxic, tasteless, colorless, and odorless gaseous byproduct of uranium decay. ‘Radon Daughters’ stick to dust particles and other surfaces. During mining, they are disturbed and float freely in the air. Ultimately, they can cause lung cancer, tumors and other health problems . In the past, radioactive tailings were also often used in the fill on which homes, schools and other structures were built.’ Pash Galbavy. Photo by Tom Alexander, courtesy Flagstaff Arts Council.

- Atomic (r)Age, Installation at Coconino Center for the Arts, Hope and Trauma in a Poisoned Land. 99′ x 21′ x 98′ ‘I chose to work with a translucent fabric to emphasize the penetrative, see-through nature of radioactive material and to place the viewer in the perspective of a radon daughter. The see-through material also references the ephemeral, fragile, and transient nature of our life experience at a time when the new Secretary of Energy (under President Trump) seeks to ‘make nuclear cool again’ in a new atomic age.’ Chip Thomas. Photo by Tom Alexander, courtesy Flagstaff Arts Council.

- Loss of Sphincter. Photographic Prints and Poems. Four prints, 21′ x 16′ each. Installation at Coconino Center for the Arts, Hope and Trauma in a Poisoned Land. Esther Belin. Photographs by Tom Alexander, courtesy Flagstaff Arts Council.

- Summoning Hózhó, Perpetuating Beautyway, Slaying Monsters, Installation at Coconino Center for the Arts, Hope and Trauma in a Poisoned Land. 64’x 34′ x 55′. ‘The deemed contamination zones in the Cameron, Arizona community are sacred sites, but for the reason that human ‘five-fingered earth-dwellers’ still survive and exist and offer corn pollen; they pray in this zone.’ Venaya Yazzie. Photograph by Tom Alexander, courtesy Flagstaff Arts Council.

- Yellow Dirt Testimony: A Promise in Many Parts, gallery view. Coconino Center for the Arts. Edie Dillon. Photograph by Tom Alexander, courtesy Flagstaff Arts Council.

- NÃÅ‚ch’I, Air; Iiná, Life; Kéyah, Earth; Tó, Water. ‘The contamination has permeated elements of everyday life that we as humans need to ensure survival The contamination is invisible to the eye, but insidious and embedded in landscapes and life.’ Amy Martin. Photographic prints, 10′ x 14′ each.

- Green Room at Dawn. Photographs, wheat paste posters, building, corn plant. jetsonorama

- Bizhi’ba Trekking through Ancestral Grief, Offering Migration as Healing lV. Digital Photograph. ‘All of this art that these women are bringing to the table is helping us to heal from past traumas,’ Yazzie said. ‘I hope that that will reverberate and help viewers who look at this work and really understand that there is some ceremonial act we all recognize. Some ritualistic tradition that we’re working through.’ Venaya Yazzie.

- Some of the thousands of lightly painted masks (re)repurposed from Yellow Dirt Testimony, A Promise in Many Parts. Thomas Fleischner.

- Viki Blackgoat Watering, Edie Dillon.

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 12, TAKING ACTION

Published October 2021