In This Issue

-

Jourdan Imani Keith ● Your Body

-

Jackie Brookner ● Valuing Dirt + Water

-

Stacy Levy ● Working Earthworks

-

Daniela Corvillon ● Wastewater In Cuba

-

Linda Weintraub ● Tragedy of Wild Waters

-

Chris Drury ● Heart of Reeds

-

Betsy Damon ● 25 Years On Water

-

Basia Irland ● The Ecology Of Reverence

-

Suzon Fuks ● Waterwheel, Women & Collaboration

-

Susan Leibovitz Steinman ● DIRTY WATER

BETSY DAMON: 25 YEARS ON WATER

EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION

This issue proudly honors BETSY DAMON, a first-generation feminist performance artist and influential environmental art role model. From China to Pittsburg, she has made significant contributions to the art and understanding of remediating water for three+ decades. Sharing expertise, she founded the “Keepers of the Waters”—an artist-run nonprofit that helps other artists and communities create their own local water saving projects.

Water is a human right. Water is an earth right. Water is the right to life.

Water ripples, splashes, soothes, tumbles, sings, meanders, caresses, pounds and thunders. Water is perhaps the most aggressive creative force on earth. It is the foundation of life.

I. Â KNOWING WATER

MY ART PRACTICE HAS BEEN one of evolving consciousness about myself and the role of art. For nearly 30 years, water has been at the heart of this practice. During the Feminist movement in the early 70’s I began performing and leading workshops, creating an art practice to empower others and myself. My adventures with water began after a US cross-country trip in 1984, where I saw many dry riverbeds. These riverbeds revealed to me the dried bones of the earth, beautiful and disturbing. This inspired the project “A Memory of Clean Water.” I cast 250 feet of the Castle Creek riverbed in Utah using hand-made paper. It was during this project, late in the day, as the stars appeared unhampered by nearby urban areas that I noticed that the patterns of the stars in the Milky Way had an uncanny similarity to the patterns in the dry riverbed.  I thought, everything is patterned by water and I know nothing of water.

The next day I learned that the waters in this sparsely settled valley were polluted from mining and agricultural run off. I resolved to learn about water. Ever since, I have become increasingly involved with those H2O molecules, the most flexible, creative, and resilient molecule.

My initial research into water led me to information about chemical additives and degradation of water quality. But, I wanted to know about water beyond simplified and technical knowledge. It occurred to me that those who lived close to the land, such as the indigenous people of the Americas, might have a broader understanding of water. Through research I discovered that very little knowledge still existed in the United States, as these oral histories had not been recorded. However I found a few water sites that were important to the indigenous people. Some areas such as the Havasupi falls in New Mexico and the Blue Hole in San Antonio, Texas were honored and protected until just recently. Sites such as the headwaters of the Sacramento River on Mt. Shasta continue to be protected.

I went to China in 1991 to visit my son who was there as a college student. Through serendipity, I met a biologist in Chengdu who had just completed research on a water site called the God Water. He found that the water helped to heal digestive problems and reduce tumors. Resolved to visit the God Water, I attained a grant in 1993 to return to China. The God Water was the source of health for a large Tibetan community. When I drank the water I felt the cells in my body open and drink in this water. Ah, so this is ‘Living’ water, I thought and kept drinking.  My guides said there were other water sources, some that were good for your heart and others for your kidneys.

At that time a water bottling company was sourcing from the God Water to sell a ‘health’ water. This endeavor failed, the water lost its medicinal value in plastic bottles and glass bottles were to heavy to transport. It was in this moment I realized that when bottled water is sold, consumers don’t know where the water comes from, what happens at the bottling site, or who else may depend on that water source. The water site is not protected from overuse and abuse.

Soon after being at the God Water, I attended the first environmental conference in Chengdu, Sichuan Province, China, put on by Chinese organizations. Attendees included engineers along with Qigong masters. This event led to me working on several projects in China, including large-scale public performance events about water quality that included Chinese and Tibetan artists. It also led to something I never imagined and what seemed impossible–an invitation to design a living water garden.

II. Â THE LIVING WATER GARDEN

THE LIVING GARDEN CAME FROM the question of how to teach people how nature cleans water.  I understood that putting water in pipes was not a solution for our infrastructures. In the 1990s, I spent time in Minnesota where I started Keepers of the Waters at the H. Humphrey Institute for public policy. Keepers of the Waters is a nonprofit organization for environmental education and remediation of water sources. In Minnesota, water was under duress. Forty percent of the 10,000 lakes had degraded water quality from farm run-off, chemicals from golf courses and other urban development. The riverbanks were being hardscaped as flooding solutions. The Mississippi River repeatedly flooded St. Paul. In a series of workshops I introduced the idea of art, science and citizen collaborations, however, it was impossible to get much traction on a project addressing water quality in a state that wanted to keep up the illusion of having clean water.

In traditional Chinese culture, water quality is inextricably linked to health, and the idea of living water was unquestioned. The Living Water Garden, built in the city of Chengdu, was the first inner city ecological park in the world with water as its theme. The 5.9-acre (2.4 ha) public park is located on the Fu and Nan rivers. Each day, 200 cubic meters of polluted river water move through a seven stage natural treatment system of various wetlands and emerge clean enough to drink. Though this amount of water is not enough to affect the river water quality as a whole, it serves as an effective demonstration project that would have lasting influence. The park also includes an environmental education center, several water features (including flow forms), and a refuge for wildlife. The entire park itself is designed to be in the shape of a fish, a symbol of regeneration in Chinese culture.

The Living Water Garden influenced many planners and designers and it laid the pathway for the vast natural water treatment in the Olympic Park in Beijing built in 2008. The team, who worked on the Living Water Garden, has gone on to do sustainability work in the surrounding areas. It is important in my work to not take complete ownership of a project. Everyone who worked on The Living Water Garden was encouraged to take ownership.  From the beginning to the end it was a collaboration.

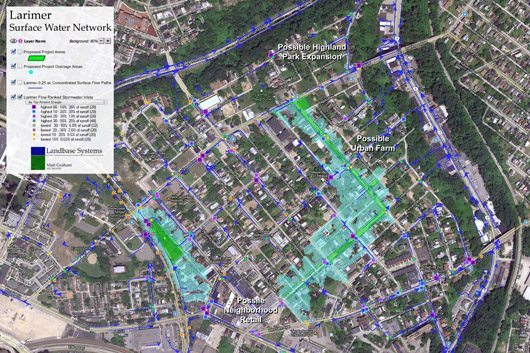

III. Â LIVING WATERS OF LARIMER: Â A FRESH INFRASTRUCTURE

Today, I am working in Pittsburgh PA with the Larimer community, on Living Waters of Larimer: A Fresh Infrastructure. It places rainwater as the foundation of a community’s redevelopment and frames the vital importance of local control over basic resources, empowering citizens to imagine what is possible.

The Larimer neighborhood reflects the plight of the environment and people under the pressure of industrialization in Pittsburgh. Larimer is situated on a plateau, surrounded by two rivers that have been buried by urban development. Washington Boulevard was built on one of these rivers and is a site of regular flooding that has caused both property damage and loss of life. As for the citizens of Larimer, it is a predominately black neighborhood that has suffered decades of disinvestment as Pittsburgh’s economy shifted away from steel.

I asked eco artist Bob Bingham, a professor at the nearby Carnegie Mellon University, to collaborate with me in Larimer. I sought out grassroots groups in the area. I reached out to community organizations. I spent time walking and talking with people in the neighborhood. I talked to local businesses. I found myself with the Larimer Green Team and the Kingsley Association, two community groups that are working to keep the identity and dignity of their community.  I  asked what they imagined for their community, what they wanted to happen there.

When I first came to Larimer I didn’t come to solve their housing or economic problems. I was there to think about their water infrastructure. However I realized that these problems are not distinct. Current urban planning thinks about storm water as waste, hence the problem of storm water/wastewater overflow that you see in many cities in the US. If we put water as the foundation of planning and design, we change the paradigm. Storm water, or rather rainwater, would no longer be waste; it would be a resource. Nearly 80 million gallons of rainwater fall on the Larimer Plateau each year. This water seeps into the ground, flows along the roads, overflows the sewer systems. It is treated as waste, and in this role, it over runs and ruins Pittsburgh’s antiquated water infrastructure.

Eighty million gallons of water could be considered an asset. It is a chance for people to live off their own footprint, a chance to have access to a resource without charge. Larimer can be a model of water self-sufficiency.

My role has been to gain community participation, to share knowledge about rainwater infrastructures, methods, and technologies. I connected with the leaders of the Green Team and the Kingsley Association.  These individuals saw the opportunity that rainwater provided. They took these ideas farther and asked how can this rainwater be used to fuel businesses, jobs, and community projects. This brainstorming has created plans for self-sustaining urban gardens, orchards, medicinal gardens, papermaking businesses, hydroponics, and water features in playgrounds and fountains. These endeavors will be visible public displays of water’s flexibility. Rainwater as a resource provides a flexible and resilient foundation for future development.

I try to be honest about the role I play. I am a white woman who is not from Pittsburgh. My level of involvement and understanding of the community has its limitations. I made it my role to give information, to open the possibilities to what can be done. I bring in local experts, and search out people who are interested in organizing and contributing to such a project. I was witness as the Larimer community stood up to politics and greed. I stood behind their leadership. Living Waters of Larimer is not my project; it is the community’s project. The first workshop we held in Larimer, four people participated. Six months later, we had over 40 people attend  We are headed to doing a comprehensive infrastructure plan, with as many people from the community involved in its conception and design as possible. We will face many challenges, as we will be questioning the old water infrastructures. Yet, even if 50% of the plan is implemented, it will be 50% more than any other neighborhood in Pittsburgh.

IV. Â RESOURCES: Â SAVING LIVING SYSTEMS

IN 2007 I OBTAINED THE RESOURCES TO explore the sacred water sites in the Eastern Himalayas. I have since then researched over 40 sites, and discovered that the Tibetans there have a living culture around water. Many of these water sites are the headwaters to rivers in the lowlands of China. I am collaborating with a Tibetan media artist, Zaxi Lhacuo in the project “ReSources: Saving Living Systems.” Together we have documented many of these sacred water sites as well as the rituals and stories that surround these areas.

The Tibetans have an intimate knowledge of their surrounding springs and water sources. Finding these sacred water sites was rarely easy. They often required days of traveling over unpaved roads, hiking, and riding by horseback up mountainsides and through valleys.

These sacred water sites are woven into the local culture with origin stories and explanatory narratives for use and care of the sites. For example, I visited a seep called the Butter Water, at the base of a forest where mushrooms and herbs proliferate. Butter Water references yak butter, a special addition to tea that is served to any visitor. In the story of the Butter Water, a starving slave woman is walking with her three-year-old son. She stops from weakness, unable to go on. Her son says that she should drink the water. She says to not be stupid, that it will not help. Yet, she drinks the water anyway and gains enough strength to walk to her next master.  Her son became a Bhudda and a monastery was built in the valley.

Locals know which sources have medicinal properties, which waters can heal your kidneys or your heart. In some villages knowledgeable doctors will prescribe water from particular springs to cure illness. The monasteries in this region are founded on such medicinal sites.

Another water site has painted red symbols on a large rock at the base of a mountain.   This red sign warns people not to graze their cattle near the waters or chop down any trees on the mountain. Other springs warn people not to bathe on threat of they and their family getting arthritis. During the Cultural Revolution, one monastery had lost all their waters when a nearby forest was harvested. The head monk chuckled when I asked him what brought back the waters. They had replanted  the trees. These stories and precautions represent a whole-system understanding of the impacts of human interference. To restrict or pollute these waters through quotidian actions such as bathing or grazing cattle will upset a balanced system that is essential for the environment and therefore the people to thrive.

During this research, my travel partners and I stayed in villages and in monasteries in the Eastern Himalayas. We talked with local leaders and discuss often late into the night the environmental challenges the villages faced. Extensive damming of rivers and nearby urban development causes water shortages in these villages where water used to run freely. These villages have to adapt to the new water conditions if they are to continue to thrive. Until recent times, the Tibetans recycled almost everything and had no knowledge that plastic caused pollution. This traditional culture has to make adaptations, such as collecting rainwater and finding ways to recycle their wastewater.

Documenting these sacred water sites was one step towards learning about a real water culture. This water culture is disappearing. When it is gone, what can we replace it with? Is there a replacement for that protection? If there is no replacement, what is in store?

We are in a struggle to save life on earth in the face of human greed. The destruction of our water systems is now familiar news. Rivers are constricted, dammed too much and diverted too often. The rivers are being used as  waste systems. Water has become a commodity to box and bottle. Linear thinking and planning has created infrastructures that are inflexible and unsustainable. We need to find an alternative relationship with our waters. We need to develop a water consciousness that will allow us to built infrastructures that work with water and provide sustainability in the face of inevitable change.