Location: California

I. CREATING A PRISON STUDIO

IN 1984 I ENTERED THE WORLD OF A WOMAN’S prison- as an art teacher. The first class I taught was drawing and that first night 23 women inmates showed up and sat at card tables set up in a hallway of California Rehabilitation Center, in Norco, east of

Los Angeles. I wanted to start with drawing a room, since I thought that creating an

imaginary personal space might be inviting. To set up the single-point perspective,

I asked everyone to start from the upper left corner of the page. I looked around

and counted- 2 women started at the upper left. Shortly after that, I found out how

common learning disabilities are among inmates. Later I realized that was only

one of many reasons that women inmates have had trouble fitting into school and

the rest of society; about 80% of women inmates also have a history as victims

of physical and/or sexual abuse. They are mostly very low income and a large

majority have 2 or more children and are single. Over 60% of women inmates are in

for drug or other non-violent property crimes.

I learned a lot from that first class, and learned more as I went on to three years

of a California Arts Council Artists-in-Social-Institutions grant, with support from

Arts-in-Corrections, a program of the California Department of Corrections and

Rehabilitation (CDCR) from 1980-2010. In 1980, each of the 6 prisons in the state

hired an artist/facilitator, who worked to supervise art, music, theater and other

classes. Until 2003, each new prison was built with a studio and practice rooms, and

each had an artist/facilitator.

California Rehabilitation Center (CRC) was an extremely incongruous prison site. It

opened in 1929 as a luxury resort hotel and it featured a marble dance floor in the

ballroom, carvings, tile murals, hand-painted ceilings, an Olympic-sized swimming

pool and mineral baths, and was supposedly patronized by Al Capone and other

famous criminals. The depression ended its life as a hotel and it later became a Navy

hospital. It passed to the state as the site for CRC in 1963. Since that time, California

has gone on to build all of their new prisons, now numbering 33, rather than adapt

other buildings.

Due to its history as a rehabilitation center, the CRC administration was supportive

of the new Arts-in-Corrections (AIC) program, which started in 1980. I was given

a small storage shed, and help clearing the old furniture, books, and racoons out

of it so that I could have 2 tables, a kiln and shelves and offer classes for up to 12

inmates at a time. The program was successful, and the following year I was given a

much larger space, the old Navy morgue, which became the studio for many years to

follow.

II. EARLY PROJECTS– INDIVIDUAL AND COLLABORATIVE

THROUGHOUT THE RESIDENCY, I WAS ABLE TO INVITE guest artists for short-term

workshops. Developing self-esteem and self-awareness is fundamental to personal

growth, which is an ultimate goal of any arts program with disadvantaged

individuals, so many of the projects focused on self-portraiture, both literal and

figurative. Although the use of cameras is heavily restricted in California prisons

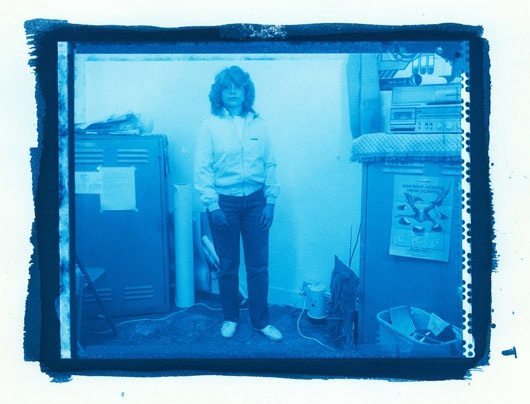

now, there were many exciting AIC photo projects in the 80’s and 90’s. In 1987, a

New York photographer with a grant from Polaroid, Robert Solywoda, came for

a series of workshops. The women used the viewfinder of the 4×5 camera and

envisioned how they would pose and what they wanted to include in the frame

for their self-portrait. They later worked with the negatives to create their own

cyanotypes in the sun. The inmates kept their prints and the B&W polaroids, and

Solywoda later created 5 editions of the 11 images. They were originally exhibited

at Self-Help Graphics in East LA, and collected by the AIC central office and Polaroid

Corporation.

On that first night of teaching drawing inside, I learned that it was important to

always teach by demonstration, rather than by verbal description alone. And my

original instinct that creating an imaginary personal space was a good project

proved true. My grant was focused on ceramics and we worked with making

miniatures of rooms, buildings and scenes, such as a beach scene from one woman’s

native Mexico or a small kitchen or bedroom from home, using slab construction.

Some wonderful miniature interior pieces came through a project taught by

an assistant to Nader Khalili, an innovative architect who supported Arts-in-

Corrections. His assistant, Debra Denker, taught the women how to create vaulted

domes from miniature ceramic bricks they cut out of terra cotta. The walls of their

buildings were slabs, and the rooms and buildings they made varied from small

houses to a multi-chambered round building created by a former madam.

Many of the women gave their artwork to their children. It served as a very

important link to family, and one that was happily free from prison references.

Maintaining ties to family and community are some of the most important factors in

successfully staying out of prison upon release.

Other successful projects used mixed media for assemblage boxes with self-

portraiture as a theme; work by Betty Saar and others was presented as examples.

Again, the small, private enclosed space formed a safe ‘world’ for the inmates,

whose lack of privacy is extreme. Those pieces led to an exhibit at Cal Poly Pomona

in 1989-‘Altars, Icons and Altered Images.’ Arts-in-Corrections supported work

going to the outside as community service, so that some programs created murals

which went to facilities such as hospitals, DMVs, schools and other public venues.

The artist/facilitators had mural crews which they were able to train in drawing,

painting and mural skills. Exhibitions also helped create a positive bridge between

the public, and the inmates, 90% of whom parole and return to our communities.

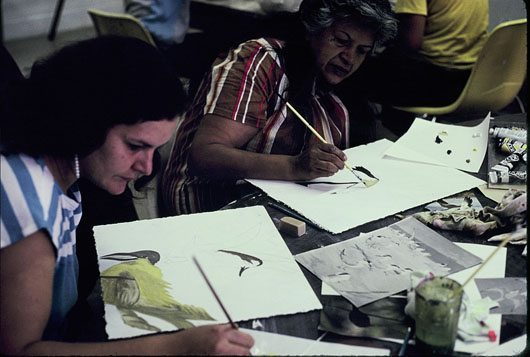

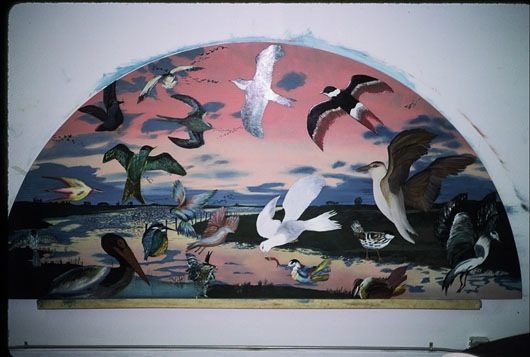

A mural created for an alcove above a CRC doorway worked well as a group project.

It was led by Tom Skelly, the artist/facilitator from the nearby California Institution

for Men (CIM). The women and he chose the theme; he painted the background

while the women painted the birds from pictures and learned to use a simple

palette, with guidance as needed.

One of the richest experiences I found inside was the studio atmosphere of quiet

talk, openness, storytelling and humor shared by a group of women working

together on their art projects. It is a rare and wonderful function of arts programs

inside, where the normal racial and other divisions that separate people and define

prison are ignored in the common experience of learning and creating. While

my individual practice as an artist involved creating more abstract sanctuary

installations during the 80s and 90s, I realized later that the studio I created at CRC

was a true sanctuary.

III. QUILTING– SOLACE AND OUTREACH

MARGOT STRAND JENSEN, A NATIONALLY EXHIBITING TEXTILE artist, worked as a full-time artist/facilitator at Northern California Women’s Facility (NCWF), Stockton, from

1990-95. Her professional background gave her a range of techniques she was able

to apply to the seemingly foreign and unfamiliar prison studio she encountered

when first hired by Arts-in-Corrections and was only given 2 days of a normal

weeklong orientation. As Margot said, she ‘was the biggest fish you’d ever seen on

the yard.’ Her new studio wasn’t set up for textiles, and her budget didn’t come

through for 6 months, so Margot had no fabric, thread or sewing machines. She was

surprised when she started to see the inmates in colorful muumuus and flipflops,

but she soon realized that the AIC studio was near the area where the old muumuus

and other used fabric supplies were tossed and she was able to pad the tables with

old blankets and use old muumuus for their first quilts. Margot taught her students

that the use of old cloth was part of the tradition of American quilting, which used old cuffs and other discarded pieces. The first project for her students was hand- stamping patterns on fabric with found objects, since piecing quilt patterns required more time and experience and was challenging with the higher levels of dyslexia among the inmates. They used flyswatters, feathers, painted leaves and old utensils to create their first pieces with fabric paint Margot had bought. The groups of women learned by making small quilts, which they treasured as projects to work on back in their cells, and which they used to decorate their spaces and give to their families.

The stitching for the quilt work was solace to them in their cells, and one of her

students in her 40’s said ‘This is the first thing I’ve finished in my life.’ The process

of learning a new art form and succeeding at it is part of the success of AIC; the

increase in self esteem can help inmates realize they have value and potential to

learn other ways to behave and support themselves upon their release.

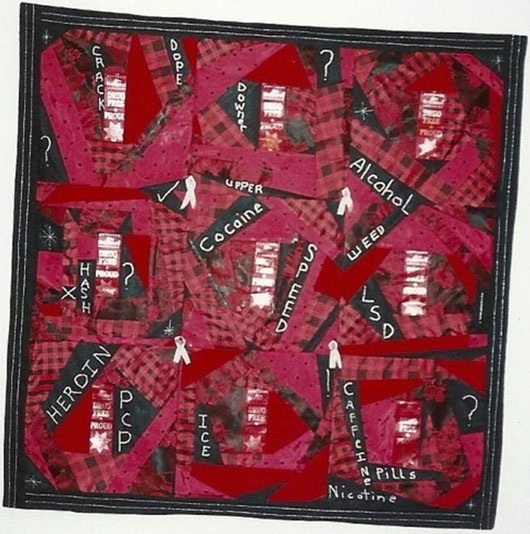

After she was assigned two inmate-clerks and was able to buy sewing machines, she

proposed that they create narrative quilts as a way to give back to the community.

Then they worked in groups on these larger pieces that were intended to go to

social service agencies, libraries, city halls, clinics and other community venues. The

women chose themes that they thought they could help teach others on the outside,

and worked in small groups creating the quilts. Two quilts pictured below included

red ribbons Margot was able to get from Sacramento when they were left over from

a school drug education program. These quilts focused on an anti-drug theme.

The quilts were displayed in a national exhibit, ‘New Directions- Quilts for the

21st Century’ at the Lesher Gallery of the Bedford Center in Walnut Creek in 1994.

Margot and her students ultimately created about 30 quilts and had them framed

and ready to donate to the community, but Margot became very ill from repeated

unannounced pesticide spraying in the studio and education area, and was never

able to return to work. A few of the quilts were at one time in Sacramento offices,

and the location of the others is unknown.

IV. PRINTMAKING AND BOOK-MAKING

THE STUDIO AT CALIFORNIA INSTITUTION FOR WOMEN (CIW) had a press, brought in

by the original artist/facilitator, Kim Kaufman. Many books and portfolios were

produced there with teachers Beth Thielen, Jonde Northcutt, Nick Capaci and others.

Fortunately, an edition of many of these are part of UCLA’s Prison Arts Archiving

Project. Some of the smaller artwork from throughout the state prison studios and

much documentation about the program has been archived permanently for study

and to serve as a model for other programs. (1)

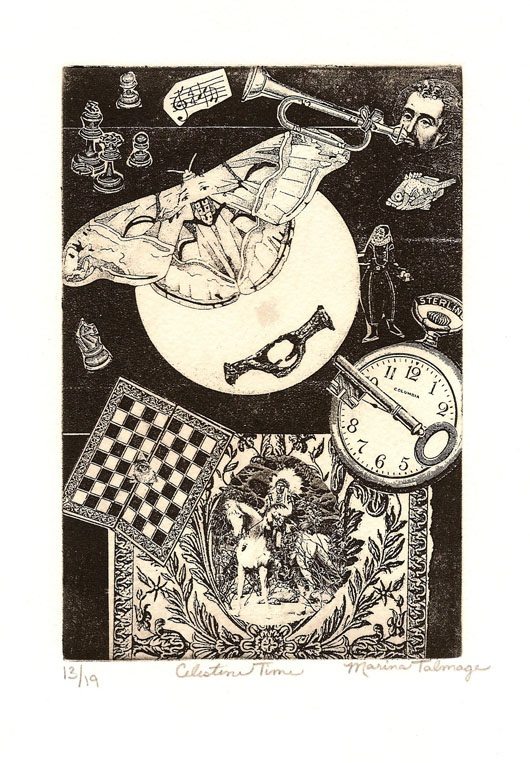

Jonde Northcutt and Nick Capaci co-led a number of workshops, teaching

intaglio and collograph printmaking, among other techniques. They brought in

photographic and other collage elements; the women also drew and contributed

their own imagery and wrote poetry for some of the editions, and a number of

wonderful works were produced.

Beth Thielen is a multi-media artist who created many technically accomplished

and beautiful pieces with women at CRC and CIW and men in many facilities,

focusing on hand-made books. One fine example is the Tower Book, which involved

printmaking, writing, and book-making in a collaboration between the women of

CRC and the men of San Quentin. The Tower Book can be displayed open or closed,

and can also be mounted on a tall freestanding base.

Beth Thielen wrote: ‘My primary interest has been to provide art classes to women

in prison. By using the ‘craft’ of book arts, I’ve been able to draw into the program

many women who might not otherwise investigate art. Through private funding, I

purchase the best materials I can find: Canapetta Linen book cloth from Italy, Irish

linen threads, archival glues, French printmaking paper… the value of the materials

reflects the value I place in my students. I bring the best to encourage the best from

them and they never fail me. Its amazing how simple and true this formula is. Works

from my classes are in collections at the Getty Museum of Art and The Library of

Congress to name a few. The purpose of the work is to give my inmate students

the proper ‘dress’ to attend the ball with. That they may become part of the

conversation about incarceration when a more enlightened perception is possible. ‘

V. ARTS-IN-CORRECTIONS: PAST SUCCESS AND FUTURE HOPE

WHEN I LOOK AT ARTWORK FROM A VARIETY of prison programs nationally, I am

frequently impressed by different elements- the honesty or the emotion or the

highly skilled style of traditional or indigenous prison imagery (tattoo art, fantasy

art, etc.) The work from California’s AIC is sometimes different because the primary

mission of Arts-in-Corrections was to ‘provide inmates with diverse opportunities

to perfect their artistic skills and personal vision through workshops taught by

professional artists who exemplified the fine arts model of quality, discipline and

inspiration.’ There is a somewhat more academic influence from AIC, and although

change and growth are indeed AIC and therapeutic goals, the program is not

modeled on an art therapy program.

AIC was the subject of several studies. One showed that inmates who participated

in the program had 75% fewer behavior problems, thus avoiding ‘write-ups’,

which cost the state money for staff time. Another study showed that inmates

who participated in AIC on a regular basis had a 27% lower recidivism (or return-

to-prison) rate, thus saving the state large amounts of money and improving the

quality of life for those inmates and their families and communities. (2) California’s

overall recidivism rate is around 70%, one of the highest in the nation.

Arts-in-Corrections was ended by the CDCR in 2010 due to budgetary reasons and

the few programs that continue in California today with local grants and support

are focused at San Quentin, New Folsom, and Lancaster, to my knowledge. Alma

Robinson, Executive Director of California Lawyers for the Arts, is leading an

effort to find grants funding and ultimately government support for arts programs

for the prisons and the county facilities, which are expected to begin receiving

more inmates as California tries to reduce the number of inmates in its severely

overcrowded prisons. (3)

With the efforts to relieve overcrowding in California prisons, and the knowledge

that programs such as AIC can help reduce recidivism, it seems that some of the

precious limited resources should be used for art programs in prisons and county

jails, with the humane, cost-lowering and positive long-term consequences in mind.

Footnotes:

(1) UCLA’s Southern Regional Library Facility,

‘Arts-in-Corrections Records, 1977-2010: Record Series 721’, Will be available

online later this Fall.

(2) www.williamjamesassociation.org

(3) www.calawyersforthearts.org

Other articles of interest:

Phyllis Kornfeld, ‘Digging for gold: Finding goodness, autonomy and great art.’

http://www.corrections.com/news/article/19177

http://buildingcommunitythroughthearts.wordpress.com/2011/05/07/mending-

hope-stitching-compassion/