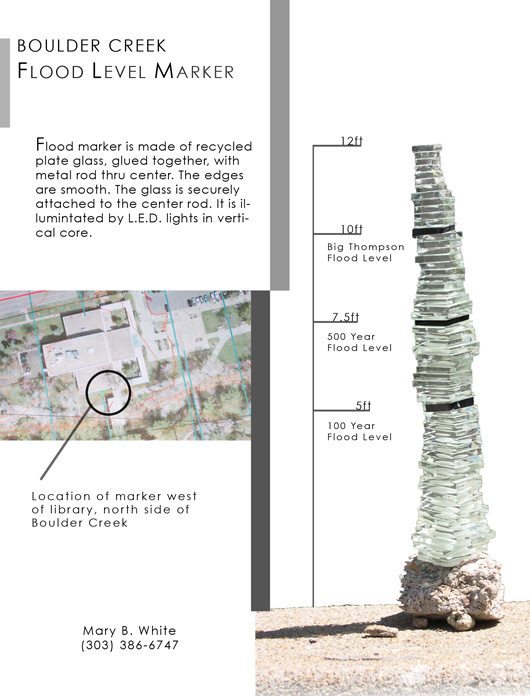

Title: BOULDER CREEK FLOOD LEVEL MARKER PROJECT

INTRODUCTION

GILBERT FOWLER WHITE, CALLED “THE MOST renowned geographer internationally of the twentieth century,’ was my father. The Flood Level Marker public art project described here is a tribute to Gilbert’s conviction that controlling and bending nature to human will is not a workable path towards global sustainability. As early as 1942, he argued in his PhD dissertation, Human Adjustment to Flood, that non-structural flood damage reduction measures should be used if cost and impact compared favorably to structural measures.This Boulder, Colorado Marker is a reminder that there are ways to live in accord with and adjust to nature, not to act as separate forces dominating nature.

The project has been a way for me to collaborate with Gilbert one last time and carry forth his aspirations.

I. THE FLOOD LEVEL MARKER DEDICATION

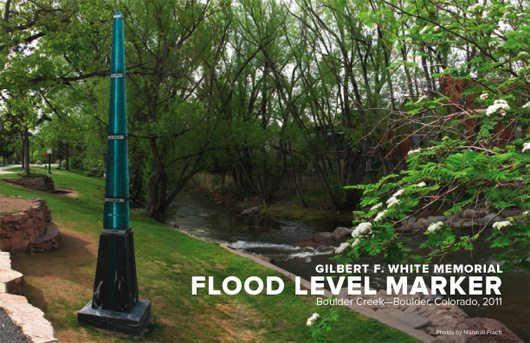

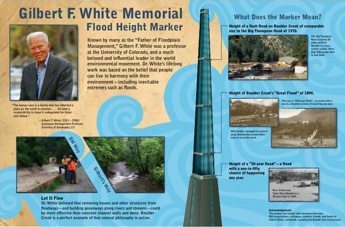

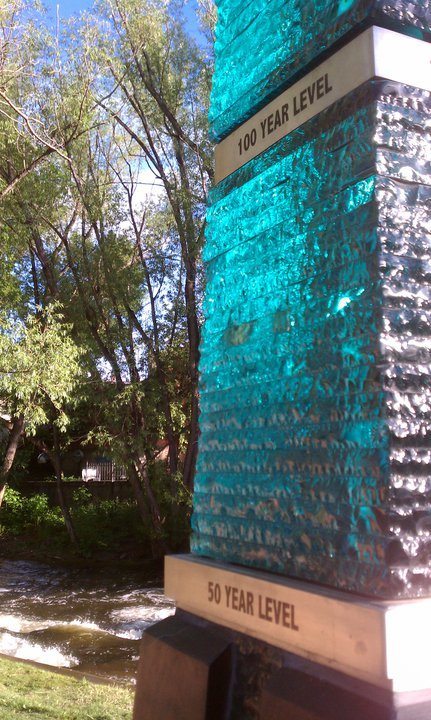

THE RAIN CLEARED AND THE SUN SHIMMERED thru Marker glass on July 17, 2011 when about 120 persons gathered in downtown Boulder CO, in front of the eighteen-foot high Flood Level Marker on the banks of Boulder Creek to celebrate the completion of a six-year project.There, the project committee officially transferred the Marker to the City of Boulder and handed the Mayor a framed copy of the plans, saying, ‘ The Marker is for the Boulder citizens: a living memorial for flood education and awareness’. The committee served Gilbert’s favorite treat–dark chocolate.

DEDICATION CEREMONY: Mayor of Boulder officially receives the Flood Marker for the City from Clancy Philipsborn, photo by Mary White, 2011.

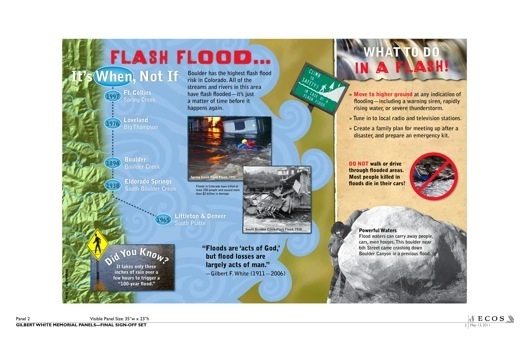

The 50 year, 100 year, 500 year flood levels, and the 1976 Big Thompson flood level (equivalent to about a 1000 year flood level) were clearly visible, dividing the sections of watery float glass. Creek path walkers stopped on our newly constructed ‘pull out’ to join the festivities, look at the marker and read two colorful interpretive signs describing what to do if there is a flood, and Gilbert’s views on water management. The creek’s velocity and volume were unusually high, and muddy waters lapped over the bank, near the Marker base.

An app code allows smart phones to connect to the web site recording the real time velocity of the creek flow . During the celebration, many joined in lively discussion of floods, the Boulder Creek water shed, and the meaning of the 100, 500 and Big Thompson levels.

II. THE SITE: BOULDER, COLORADO

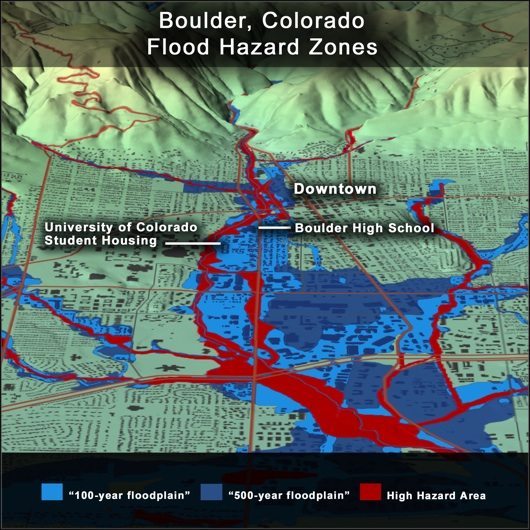

BOULDER HAS A HISTORY OF HIGH RISK FLOODING and more floods are predicted. The City of Boulder is located at the base of Boulder Canyon. Three tributary creeks feed into Boulder Creek just before the waters leaves the mountains and flow thru the central part of Boulder. The extra flow and collapse of Barker Dam at the top of Boulder canyon contribute to a possibility of extreme flooding events. The first recorded photos of documented flood damage on Boulder Creek are from 1894, when a 100-year level flood swept thru the middle of town. Smaller floods occurred in 1914, 1919, 1921, 1938 and 1969. (1)

In 1969, a moderate flood impacted Boulder, causing $5 million in damages, much more monetary loss than before.In 1976, a flood occurred in the Big Thompson Canyon, just north of Boulder Creek, with a record water level equivalent to the predicted 1000-year flood. At least 139 persons died in the flood, and 88 were injured. Seven people were listed missing. The flood destroyed 316 homes, 45 mobile homes and 52 businesses. (4,8,9).

Four to five inches of rainfall in a thunderstorm could cause a fourteen-foot high wall of water that would reach Boulder in 45 minutes.

A devastating flood of the same magnitude as Big Thompson is predicted to hit Boulder. It is more of a matter of ‘when’ than ‘whether’ it will happen. The question is whether or not people will be able to respond quickly enough to get to higher ground. Many public and private buildings and businesses are in harm’s way. The question is how many buildings will be damaged, how many lives lost and how much property damaged. Historical and present choices about what is built in the flood plain effect residents and future generations.

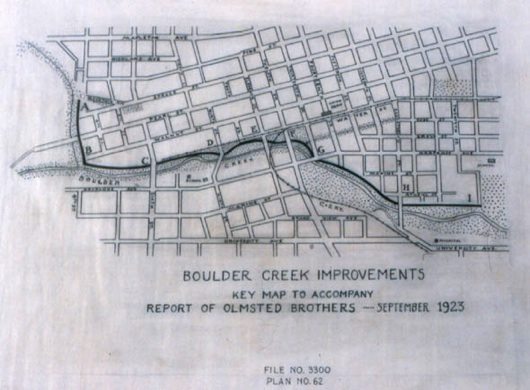

Differences of opinion about structural or non-structural flood mitigation started at the turn of the century in Boulder. Then the creek was a reciprocal for city waste. In 1910, pro-active citizens invited Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., a well-known landscape architect (his father Frederick Law Olmsted designed NYC’s Central Park) to revision the Boulder creek corridor. Olmsted suggested several ways to bring back the creeks as a beautiful part of the community and to move towards a ‘greenways’ orientation.

In 1910, Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. warned the Boulder Civic Improvement Association of the dangers of encroaching upon the floodplain of Boulder Creek (Olmsted 1910). His report described the possible scenario of filling the land near the creek with private uses,

‘…thus restricting the flood channel of the stream and sooner or later causing calamitous floods. This is on its face a plain, straightforward question of hydraulics and municipal common sense. If the people of Boulder only have the sense to take warning by the experience of other towns they will deal with it now, while it can be dealt with cheaply and easily, instead of waiting ’til a catastrophe forces them to remedy their neglect under conditions that will make a solution far more costly and less satisfactory.’ (2)

Olmsted recommended against the construction of a deep, artificial flood channel. Instead he suggested that Boulder Creek be allowed to remain in a small, shallow channel for the ordinary stages of the stream, with occupation of a much broader floodplain during larger storms. Recognizing the need to dedicate the land to a useful purpose, he suggested the plan of ‘keeping open for public use near the heart of the city a simple piece of pretty bottom-land of the very sort that Boulder Creek has been flooding over for countless centuries’ as the cheapest way of handling the flood problem of Boulder Creek (Olmsted, 1910).

If the city had implemented his recommendations in the 1920s, there would be less flood risk now in Boulder. Instead, thru the 1950s, the town continued to add housing and channeling to Boulder Creek.

After another flood, the 1960’s marked the City’s first serious effort in flood control. Initial investigations focused on the then-traditional flood mitigation techniques, such as hard-lining stream channels and using concrete structural facilities to channel stream flow.By chance, Boulder became a site for one of Gilbert’s early flood plain management studies in the mid 1950s, when our family started spending summers in Colorado. It was at that point that Gilbert embarked on a six decade quiet and persistent education of Boulder citizens and policy makers about sustainable growth, using the flood plain for recreational use and building on higher ground. (3)

III. NATIONAL FLOOD PLAIN MANAGEMENT POLICY: GILBERT’S CONTRIBUTION

ROBERT HINSHAW, IN HIS BOOK Living with Nature’s Extremes, the Life of Gilbert Fowler White, describes Gilbert’s career. (Robert met my father in 1951 during Gilbert’s tenure as president of Haverford College.)

Gilbert received many honors in his life but Robert writes that three awarded in 2000 best represent the scope of his work: the National Medal of Science, the U.S. National Academy of Science outstanding citizen-scientist Public Welfare Medal, and the international Water Resources Association Millennium Award.

The following descriptions are taken from the citations accompanying his many awards.

Gilbert White was a Gustavson Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Geography at the University of Colorado at Boulder. He has been called ‘the most renowned geographer internationally of the twentieth century,’ one who ‘personifies the ideal of a natural resources scientist committed to stewardship of our planet.’ ‘He has educated the nation and the world on how to change the ways we manage water resources, mitigate natural hazards, and assess the environment.’ (4)

Throughout his life and many international projects, Gilbert encouraged a global consciousness among scientific communities, public awareness of human accountability for the earth’s environment and international cooperation among policymakers to address environmental problems.Gilbert’s scientific ideas on river management were very controversial for the 1940s. He challenged the national philosophy and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers policy of controlling rivers of the 1930-1970s. From 1933 through 1939, he served as staff secretary on a succession of water and land committees under Nation Resources Planning Board auspices including the Mississippi Valley Committee.

Gilbert became convinced that it was folly to occupy floodplains assumed safe from normal flooding because they were protected by dams and levees. Increased occupancy, he foresaw, would only result in increased losses when extreme flooding overcame these structural barriers.

Perhaps his many varied positions contributed to his outlook. From 1940-42 he worked for the Bureau of the Budget in the Executive Office of the President, providing President Roosevelt with daily environmental and natural resource information. As a convinced pacifist, in 1942 he quit to do relief work in Vichy, France. After WWII ended, he became President of Haverford College and had little time for scientific research. But he kept investigating. In 1950,Gilbert served on the committee preparing the recommendations for A Water Policy for the American People, Report of the President’s Water Policy Commission. (5) The committee took risks when they offered caution to the trend to build levees and channel rivers.

“There is a sobering finality in the construction of a river basin development; and it behooves us to be sure we are right before we go ahead.”

The story Gilbert told me was that in 1955 Margaret Mead came to dinner and said ‘Gilbert, now that you are a school administrator, you will never go back to science’. That night he talked to my mother, he knew he must go back into water resources research, it was too important. He found a position as Chair of the University of Chicago Geography Department , and refocused on water resource policy in 1956, the same year our family discovered Colorado.

IV. LOCAL FLOOD RESEARCH: GILBERT IN BOULDER

CIRCUMSTANCE MADE BOULDER THE SITE for one of Gilbert’s early flood plain management studies. Dad worked on his father’s ranch in Wyoming as a boy and learned a deep love of the natural world. He wanted his three children to experience the same closeness to nature and connection to the land. Spring 1956 he asked his graduate students at University of Chicago Geography Department if anyone knew of a ranch in the west where he might take his family; where he could write and do research during the summers. Jackie Bayer, one of the first women PhD students, suggested a working ranch in Boulder’s Sunshine Canyon. She knew the rancher took his cattle up to the high country during the summers and needed someone to mind the low country ranch and old animals near town July and August. Would we be interested? Thrilled, Dad called the rancher, Leonard Wittemeyer. A rental was arranged quickly. That summer we packed up the Chev station wagon, heading west to the Wittemeyer homestead. Summer 1956, we settled down in the log cabin in Sunshine Canyon to tend the old mare and ancient bull. We explored the mountainous terrain, and Dad started writing.

Gilbert immediately realized the flood risk in Boulder. Boulder Creek was corralled into a cement channel, using structural methods to control the water flow and mitigate flooding.

Many public buildings were in the process of being built on the flood plain, including the library, the police and emergency center, the jail, the high school, and University of Colorado married student housing. It was hard to influence public policy.

He often told students that local action could create national change. Following his own advice, he organized a graduate research project on Boulder Creek to document building and development on the flood plain, and later used his experience to help design the national flood insurance policy.

While the 100-year flood is the standard used for flood insurance, he believed that communities needed to be prepared for a 500 year flood event.

After 14 years of summers in Sunshine Canyon and winters back in Chicago, my parents moved to Colorado in 1970. Gilbert and my mother Ann lead the mid-1970’s effort to develop an open, natural stream corridor along Boulder Creek through the City, as an alternative to a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers vision of a concrete-lined channel. He was thrilled to have the first flood warning signs approved.

Gilbert accepted a position as the Director of the Institute for Behavioral Science at University of Colorado, Boulder. His work took him to many other parts of the world to consult and research on environmental issues and water resources, for instance: The Aswan Dam in Egypt, the Mekong River Delta, and an east Africa domestic water use study. He was interested in the decision making process, about water resources and natures’ extremes. He founded the Natural Hazards Institute at UC. But throughout his life, he never forgot local action encouraging awareness of flood risk on Boulder Creek.

V. COLLABORATIVE CRAFT/ARTS EDUCATION PRACTICE: My BACKGROUND

FLOOD MARKER INSTALLATION CREW: David Butler, Mary White, Christian Mueller, Clancy Philipsborn, 2010. Photo by Charles Harvey.

WHAT IS MY BACKGROUND? MY INNATE SKILLS AND talents guided me into a career as an artist, and I look for ways my skills as a visual artist can contribute to an understanding to environmental science and sustainable development.

Thanks to Dad, I absorbed a comprehensive ‘hands on’ natural resources and water shed management training by age 16. My father often took me on field trips to study the effect of erosion and flooding, even to the Mississippi River delta. Natural resource decision making was the topic of conversation around the dinner table. At least twice a year during my childhood, our family drove across the country in the old Chevy station wagon, surveying flood plains, watersheds, geological formations, carefully inspecting regional topographical maps.

As we approached a known flood plain with many buildings close to the water, Dad would shake his head and exclaim, ‘Would it have caused less suffering and damage if the flood plain were not built on? ‘Why build all those homes, the school and the library on the flood plain’? ‘Would the levee present a false sense of safety? Would the levee hold a 500 year flood?’, ‘Was the dam the best form of flood mitigation for the town?’ When we drove into a city with greenways along the creek, Dad joyfully pulled over to photograph and point out how flood waters could be absorbed by the greenery, unlike concrete channels. .

Home from art school and teaching in the Bay Area, I helped him trim nearby trees for fire mitigation, file and organize papers for his reports on the effects of man made lakes and dams, the UN Lower Mekong River basin study, (a study that he had hoped might have been a way to bring peace in the area) and many other water resources related projects. I listened and learned and have tried to use the knowledge in my art practice.

I received a BFA in Ceramics and Secondary Credential from the California College of the Arts (CCA), Oakland CA, by 1970. I am drawn to art forms that glide between art and craft practice, that evoke many senses: touch, sight, light reflection and transparency, are collaborative in practice and are a hub of interdisciplinary exploration attracting scientists, artists and engineers. I taught high school art and design in inner city Oakland 1971-1979, integrating community projects, for instance signs for the local health food store and twenty local murals.

In 1980-82 I returned to CCA to work on a MFA in Glass/Painting, focusing on images of relationship of humans as part the natural world, not separate from nature. I then ran an independent studio designing and making CA fauna and flora vessels for the Nature Company. From 1986 until retiring in 2005, I was instructor and studio coordinator for the Glass Area in the School of Art and Design, San Jose State University, as well as teaching 2 D design, Community Concepts and Creative Arts Seminars. We organized the SJSU studio as a laboratory to encourage collaborative interdisciplinary projects, bringing in many diverse artists and designers. We brought innovative energy efficiency measures to our studio in the mid 1980s, and my own work moved to only use recycled and repurposed materials. Serving on the Board of WEAD has offered me a way to be very active in bringing more attention to environmental art projects.

I began to teach part time at the Crucible, in Oakland, whose mission is to bring together art, industry and community in an ecologically sustainable way. Our roof has 210 solar panels, we have a vibrant youth and bicycle program.

WATER GATHERING PLACE, collaboration with Andree Singer Thompson, Christina Bertea and Mary White, WEAD Sponsored Bioneers 2010 Installation.

Most of my work has been consciously collaborative; there is a magic and synergy in the gathering of minds in the creative process that can bring richer and more sustaining solutions. When I ‘rewired’ from SJSU in 2005, I hoped to reach a new higher level of collaboration between my art practice and environmental issues.

VI. FLOOD AWARENESS: COLLABORATING WITH GILBERT IN HIS 90’s

IN 2005, I MOVED TO BOULDER TO BE NEARER Dad, age 93. I helped him with his daily correspondence. One day I read him a notice that developers proposed building a new convention center downtown next to Boulder Creek. Gilbert immediately dictated a letter for me to send to all members of the Boulder City Council. He wanted to encourage them not to grant more building permits on the flood plain and to continue to preserve the flood plain surrounding the creek for recreational purposes.

As a sculptor and arts educator I knew the extraordinary power of visceral physical forms and kinesthetic experience vs. documentation by text and charts. I wondered if creating the actual 16-foot height of the historic floodwaters, or the 18-foot predicted level, along informational text about the creek waters and floods, would be an effective contribution to flood education? How could I as an artist work with the scientists and flood research to create an accurate and aesthetically intriguing vehicle for provoking curiosity and alerts about floods? Scientists often have the research and proof, trying to change policy and awareness is the challenge.

I had worked on collaborative projects with Dad in the early 1970. He and my mother were studying domestic water use in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda villages, including water carrying vessels. (6) At the same time Gilbert was active in the revision of the Clean Water Act in 1972. Gilbert and I discussed the issue of public awareness and I made him a series of hand blown water glasses with soft facets in the glass that made the portable water sparkle and reflect in brilliant ways.

Dad gave the glasses to policy makers and activists all over the world. It was a way to highlight the value of a precious resource: drinking water. Over the years we had many ideas for projects related to flood mitigation and water resources, but only a few had materialized. This was a chance for another venture! After mailing the letters I made a small model of a stacked glass flood marker, an 8′ high model scaled down from the proposed 18′ height. I was auditing a green architecture studio class with Julie Herdt at University of Colorado Boulder and was encouraged by the class to pursue the idea. After showing it to the class, I showed it to my father, Marshall Frech, flood filmmaker who was working on a film about Gilbert, and Alan Taylor, who had just retired as the City of Boulder Flood Plain manager. They all thought a physical marker might have a chance of being accepted by the city and were enthusiastic about the idea. We walked down to the creek and looked for suitable sites and made general plans to approach the City, but did not get around to doing so. In the end, this modest, quickly made model of found materials was the seed for the six-year project. Over the years I have marveled how small quick visual forms can bring forth action.

Thru Gilbert, I met Boulderites who understood the flood risk issue and the larger issue of living integrally as a part of natural forces, with sustainability practice, who were passionate about stewarding the precious natural resources of the earth. For instance, he introduced me to painter and arts activist Elizabeth Black, founder to the Boulder Eccentric Gardens project and a leader of the Silver Lake Ditch irrigation group. Over the years, she spent many hours with Gilbert plotting an idea of putting up round markers that indicated the 500-year flood level on residential and business buildings on the flood plain in Boulder. They had no success with manifesting the marker idea, since many building and business owners were adamantly opposed to having the markers on ‘their’ buildings. Elizabeth later helped initiate the Flood Marker project. Everyone who later formed the flood marker committee (with one exception) enjoyed many conversations with Gilbert on Boulder sustainable growth and flood plain management.

The original proposal and model I showed Gilbert in 2005. Notice that the height had to be increased by 6 feet in accordance with the accurate flood levels.

VII. A MEMORIAL: HONORING FLOOD EDUCATION ON BOULDER CREEK

WHEN GILBERT PASSED AWAY AT AGE 94 October 2006, the Boulder City Manager asked Molly Tayer, a City and community facilitator /consultant if she might explore the idea of putting up a plaque on Boulder Creek to commemorate Gilbert. Molly and Gilbert had often met for lunch to discuss local Boulder environmental issues. She respected his long tenure of bringing awareness to Boulder Creek floods.

Molly met with Elizabeth Black. They formed a committee to discuss the commemorative plaque idea and invited David Butler, worked with my mother and father as the Natural Hazards Observer editor at the Natural Hazards Institute. Alan Taylor, who was for many years the Boulder Flood Plain manager, joined the group. Earlier in his career, Alan, with the encouragement of Gilbert, had been able to convince the City to start buying back houses along Boulder Creek that were likely to be flooded and create a mitigation plan for the Boulder High School, dramatically reducing the risk and damage caused by inevitable floods.

I was invited to join the committee and show them the model for the flood marker that I had shown Gilbert, Alan and Marshall, thrilled to be included. All agreed that Gilbert would not want a plaque, but might be supportive of a flood marker that was educational, created curiosity about the creek, water resources, and flood risks, and provoked the viewer to learn more about the natural systems of the creek, water shed, water resources and natural forces in general. Gilbert had often started with local projects that were later taken to national policy.

A flood level marker seemed appropriate because it was a local project in his home town that provoked thought on all water issues and would stimulate conversation on care and protection of natural resources and sustainable development. Elizabeth designed the first fund raising brochure and we set about working with the city departments.

By Dec. 2006, in the spirit of my father’s aspiration that science, particularly geography, should be useful and integrated with society and the humanities, a diverse committee of 17 gathered to guide the project. We shared Gilbert’s aspirations.

VIII. LISTENING AND LEARNING: THE DESIGN AND APPROVAL PROCESS

IT TOOK SIX YEARS FROM THE INITIAL IDEA TO get all the necessary permits and raise enough money to construct the marker.

Gilbert always encouraged lively interdisciplinary study between scientists, practitioners, researchers and policy makers. He wanted to find ‘practical’ applications for his research, on local, national and international levels. He encouraged collaborations, creating a forum for every voice to be heard, and for the decision making process to be carefully and thoughtfully considered as it moved along. Following his Quaker faith, he encouraged ethical and open negotiations, with every dissenting opinion heard and listened to. He knew that policy could not be changed quickly and was willing to attend required meetings and then more meetings and more negotiations, whenever necessary.

We tried to run our project committee with same spirit of consensus decision making and patience Gilbert modeled during his life. The process was different from art projects where one artist receives most of the credit. We each contributed special skills from science to the humanities and aspired to a lateral communication structure.

Everyone on the committee contributed special talents and expertise. Molly Tayer and Alan Taylor volunteered to be the first two project managers and got the project rolling. Clancy Philopsborn, who had written his PhD with Gilbert on the original Boulder Creek flood research, took over as project manager for the final two years of the project. Alan and Clancy made sure the flood levels were accurate. Elizabeth designed our fundraising brouchure that explained the project and Photoshopped the small flood marker models to create the illusion of larger scale. I made models, and many more models as the design evolved after meetings with city departments. Christian Muller was the on site artist, working with me on the design and construction. He built the stone parts, I built the glass. He worked with the engineer and landscape contractors. David Butler was our gracious editor for all the text and helped on every part of the project. Claire Sheridan, Gilbert’s second wife, moved along fundraising and wrote the thank you notes to all the donors, Diane Smith and Kathleen Tierney helped us present the project at the Natural Hazards Workshop. Water engineers Ken and Ruth Wright offered wise fundraising and logistical advice, Oakley Thorne of the Thorne Ecological Institute offered wisdom on wathershed and creek science.

Flood Marker Dedication led by Clancy Philipsborn, Master of Ceremonies, Photo by Mary White, July 2011.

It took about a year to identify and go thru the approval process for a site for the marker. Many of the city’s early concerns regarded a location had to do with the environmental impart on the wetlands along the creek, vandalism and safety, rather than a critique of the idea of a marker. Three sites were suggested to the City. The original design was all glass and City concerns of vandalism and safety quickly encouraged us to design a stone base. Alan designed the first Power point presentation to present to the first of many City department meetings and discussions, photo shopping in the first visualizations of the final marker. In the middle of the process, the City architect suggested several useful revisions that we then made. Alan and Clancy determined the exact height of the 50, 100, 500-year levels. From the very beginning and original design, we consulted with a local water engineer John Arnu, an avid river rafter, on the correct construction and size that would withstand floodwaters. Over the course of the project, I made at least eight different models of the marker and material samples, as each department expressed needs and concerns.

-We made presentations to the Natural Hazards Workshop, the Association for Flood Plain Managers, local FEMA staff, local engineers, City Departments and Boulder Quaker Meeting.

All the sessions turned into stimulating sessions on flood mitigation on the Front Range and water resources. Alan Taylor designed and taylored each presentation for each meeting.

-We contacted Gilberts academic and governmental colleagues with a project proposal.

-I collaborated with National Geological Survey Hydrologist Sheila Murphy on a series of glass graphs of the Boulder Creek flow rate at an exhibition piece in glass exhibition in the Boulder Library in an enclosed walkway that goes over the creek

-Flood film maker Marshall Frech provided a short film on Gilbert we showed at presentations and sent to thank generous funders- On behalf of the Gilbert White Memorial Committee, Randall H. (‘Clancy’) Philipsborn, our Project Chair, applied for and received a Boulder Arts Council project award for a $5000 Major Grant. He is the first Geographer, Flood Plain manager to receive this arts award!

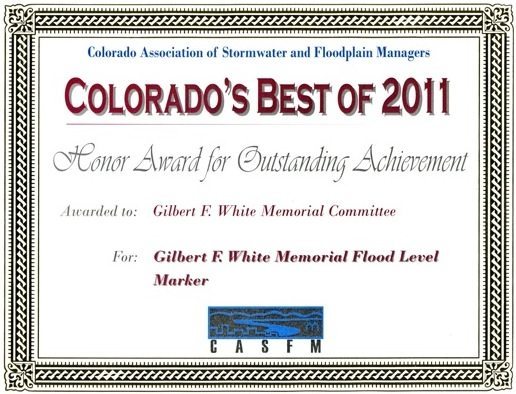

-In July 2009, we went ahead with the Groundbreaking Ceremony even though the final building permits were still not approved,. We sent an e-mail invitation to all floodplain managers in the state of Colorado (200+) to attend the Groundbreaking Ceremony. The invitation was circulated by the Colorado Association for Stormwater and Floodplain Management (CASFM), who became a donor organization for the project.

It took the water resources ‘village’ to raise the flood marker. We were able to pay for the project with over 444 individual and institutional contributions and over 50 in-kind donations. We worked with the Boulder Foundation as our 501c3 umbrella organization to raise over $120,000. While the total estimated cost increased by almost 25% from the original budget, we were able to raise funding sufficient to pay all expenses. Variances between budgeted and actual costs were many and varied, including using a budget developed 2+ years prior to construction with no allowance for increased costs, underestimating the need for additional construction equipment (tractor, scaffold, pumps, broken equipment, filter-bags), unplanned expenses (needing an additional concrete pour, problems with drilling anchoring piers, and underestimated costs (e.g., drilling, permits, signs). We thanked the generous donors with ‘center bore cores’ I drilled out of each piece of glass and inscribed ‘GFW Memorial Core Bores’.

Christian Muller, collaborating artist, tightens the bolt on the 500 year flood section, photo by Charles Harvey.

Four members of the original committee became the volunteer crew for the final construction. Christian was the on site organizer to dig and put in the foundation while I fabricated the glass sections in Oakland, California, working with Dorothy Lenehan of Lenehan Architectural Glass and her colleague Trudy Barnes. We fabricated the 50 year, 100 year, 500 year and Big Thompson levels in Dorothy’s shop and shipped them to Boulder. Trudy Barnes and her husband Chris Pavicich made a fantastic time lapse video that shows the construction process we went thru to make the glass sections. (7) Two months work in three minutes!

I arrived in Boulder in time to help with the foundation preparations and install the marker with Clancy, David and Christian.

At the site, construction staff included a paid (at a significantly discounted rate) construction manager, several dozen workers under our specialty sub-contracts (for excavation, pier-drilling, cement pours, stainless steel fabrication, cutting stone, sandblasting marker levels, etc.) Within our committee, we had a ‘core’ group of 4 volunteers that each spent significant time with project coordination, errands, and actual construction of the monument.

The final design differed only slightly from detailed design drawings. The structure itself was moved a few feet away from the original creek-side location to accommodate underground utilities and pipes and to achieve the proper angle and depth of the anchoring piers drilled as part of the foundation. The overall height of the structure was reduced by 18′ to meet local height codes. We were able to wire the internal LED lights so that they are powered by solar panels on the city council building nearby. One of the internal LED light strands was disabled after construction because it was just too bright. We wanted the structure to be visible at night, but we did not want it to be a nuisance.

IX. MARY MISS CONNECT THE DOTS: 500 YEAR FLOOD

IN 2007, WHEN WE WERE IN THE MIDST OF FUND raising and waiting for City permit approvals, artist Mary Miss was invited to do a project in Boulder as part of the Weather Report: Art and Climate Change exhibition at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, curated by Lucy Lippard. Each artist worked with scientists. Mary decided to work on floods, and worked with Hydrologist Shiela Murphy and Soils engineer Peter Birkland. I was very excited to learn about her project. Her piece would bring more flood awareness to the community. I contacted Mary and was able to help her a little bit on the installation. Mary hung blue dots on trees and buildings at the 500 year flood level. She taped them on Naropa University steps and on the front door of Boulder High School. It was a brilliant temporary project, the kind my father and Elizabeth Black had visualized many years ago. Mary’s project illustrated the difference between a temporary art installation, and a permanent site that is approved and forwarded thru a governmental process. As a temporary project, Mary did not need such approval. When the Boulder High School principal objected to the dots in the middle of the school front door, she was able to tell him it was a temporary art installation, and they would taken down at the end of the show.

Our project had a different process. We knew that Gilbert would have wanted agreement for all actions, with all parties in accord, as the process moved forward moved, ever so slowly, thru specific permits and approvals from the City Parks, Building, City Council, City Architect, City Building. Every detail had to be approved. It was fun and encouraging to see the spontaneous response to the dots and Mary’s beautifully executed idea.

BLUE DOTS PROJECT: blue dots indicating the 500 year flood level, Mary Miss, Boulder High School, photo by Mary White, 2007.

Mary Miss’s project also brought our attention to the use of text. The dots did not have any text. The public entered the gallery to read about the dots meaning. We knew that interpretive signs, in the spirit of the many other educational signs on the creek, would be an integral part of our plan.

X. PUBLIC FLOOD EDUCATION SPACE: AUDIENCE AND INTERPRETIVE SIGNS

THROUGHOUT CONSTRUCTION WE WERE AMAZED at how many people stopped and ask detailed questions regarding the sculpture and the meaning behind it. We were not able to design the interpretive signs until the construction was done. It got to the point where we started developing a ‘handout’ for passersby just to keep constant interruptions to a minimum. We finally printed two temporary project description signs and hung on a near by tree to address most, if not all, of the questions viewers might have.

July 2011 we finished the permanent two interpretive signs. The text was carefully crafted by David and Clancy, and designed by Eco Design, that same group that has designed the many educational signs on the Creek path. We created ‘temporary’ signs (with duplicates, in case they are vandalized) that will last 3-5 years, while the City completes their concurrent work on a master creek-path sign plan.

Creek visitors stop, look at the sparkling glass, then read the signs and look again. The viseral experience of standing by the marker gives a real view of how high the flood levels will be. Hopefully the signs give clear advice: “Climb to higher ground, Do not get into your car!”

During the first year of planning, the City recommended that we construct a ‘pull-off’ adjacent to the main bike-path so that those enjoying the Memorial wouldn’t impede pedestrian and bicycle traffic at one of the paths busiest areas. It proved helpful, as groups of four or five pedestrians stop to read the signs and look at the marker and would have blocked the rapid peddlers on the bike path.

The marker is in the middle of a thriving downtown. We estimate thousands of people, each year, will walk or bike past the Memorial site. Many commuters to UC Boulder, the library and the high school use the creek path, and the museum, restaurants and the farmers market is 50 feet away.

XI. CONCLUSION

IT IS IMPORTANT THAT CREEKS FLOOD. We are the stewards of creeks and their water sources, we are stewards of precious water resources. Choose not to subvert creeks but value and work with them in their cycles.

Gilbert was the real collaborator, in spirit, on the project. His ideas guided and permeated the entire process. Presented with frustrating challenges of the lengthy permitting process, many on the committee would ask, ‘What would Gilbert do now?’ Perhaps his answers are in the following quotes?

Gilbert was asked to contribute to National Public Radio the This I Believe Radio Program in 1951. He describes beliefs that guided his life until his death.

We can be confident that action which is in accord with a few basis beliefs cannot be wrong and can at least testify to the values we will need to cultivate. These are the beliefs that the human race is a family that has inherited a place on earth in common, that its members have an obligation to work toward sharing it so that none is deprived of the elementary needs of life, and that all have a responsibility to leave it undegraded for those who follow.’

Just before he died in 2006, This I Believe contacted him to ask his current beliefs? He added the following.

‘As my Quaker mentor, Rufus Jones said, if one can look for the ‘light’ in every person, even if one disagrees with her or him, then one can find new paths to understanding. And, as many well know, it is one thing to hold certain beliefs, and another thing to consistently put those beliefs into practice, as we work together for the stewardship of the earth and all of its inhabitants.’

We hop to contribute to these beliefs with the flood marker project.

End Notes

(1) http://bcn.boulder.co.us/basin/history/floodhistory1.html

(2) http://www.bouldercolorado.gov/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=4176&Itemid=1616

(3) The Tributary Greenways Program (or Greenways Program) is an outgrowth of the Boulder Creek Corridor Project, a plan for the preservation and development of Boulder Creek, developed in 1984. http://www.bouldercolorado.gov/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=5091&Itemid=1196 & http://www.bouldercolorado.gov/files/Utilities/Greenways/2011/2011_Greenways_Master_Plan_Update_FINAL_6_8_11.pdf

(4) Hinshaw, Robert. E. 2006. Living with Nature’s Extremes: The Life of Gilbert Fowler White. ISBN: 1-55566-388-5. Boulder, Colorado: Johnson Books.

(5) A Water Policy for the American People, Report of the President’s Water Policy Commission. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

(6) White, Gilbert. F. David J. Bradley, Anne U. White. Drawers of Water: Domestic Water Use in East Africa. University of Chicago Press, 1972.

(7) Film about construction of glass part of marker. Film made by Trudy Barnes and Chris Pavicich: http://gallery.me.com/

Photo End Notes

(1) http://www.boulderfloods.org/

(2) Natural Hazards Mitigation Video interview with Mary White by Bill Barton, 2011. http://www.youtube.com/

Special thanks to all Flood Marker Committee members, City of Berkeley staff, Boulder Citizens, Natural Hazards Center, University of Colorado, engineer John Arnu, McGinty Design, Kathy Bradford, Joanne Howard, Robert Hinshaw, Frances Chapin, Will White, Association of Flood Plain Managers, Colorado Association for Storm Drain and Floodplain Managers and all donors.