Introduction to The Crochet Coral Reef

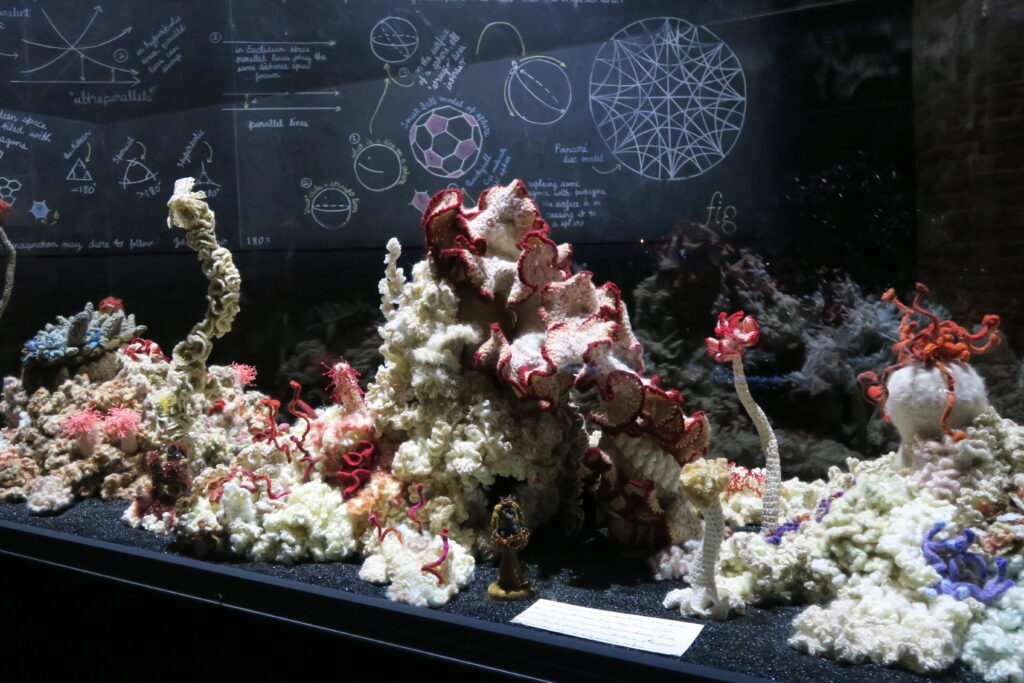

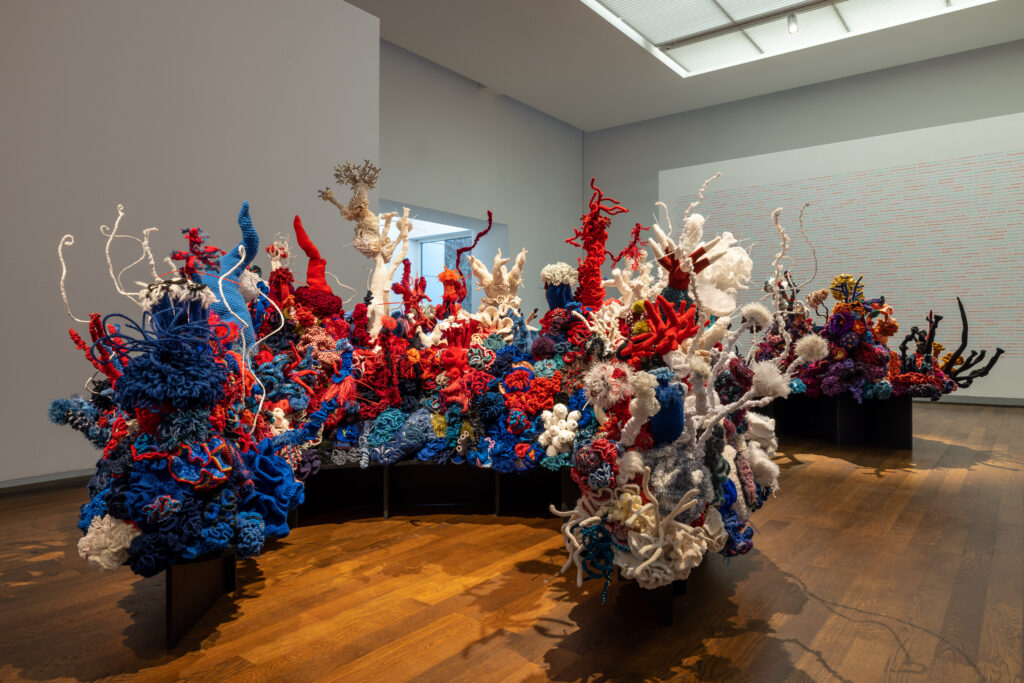

A project by Christine Wertheim & Margaret Wertheim of the Institute For Figuring, the Crochet Coral Reef is an artwork responding to climate change and also a global community-based exercise in applied mathematics and evolutionary theory

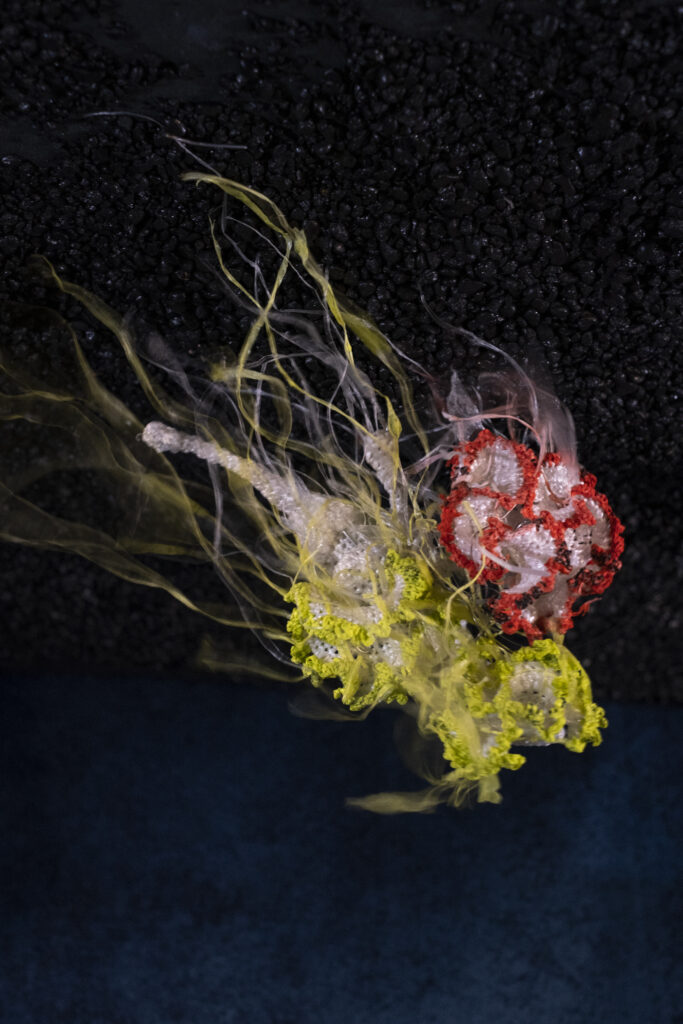

At a time when living reefs are dying from heat exhaustion and our oceans are awash in plastic, the Crochet Coral Reef offers a tender impassioned response. This is a crafty retort to climate change, a one-stitch-at-a-time meditation on the Anthropocene.

Like the organic creatures they emulate, these handmade sculptures take time to make – time that is condensed in the millions of stitches on display, time that is running out for earthly critters including humans and cnidarians. Time forms a framework for the project, for as CO2 accumulates in our atmosphere time is increasingly in short supply and what we choose to spend time on is a reflection of our values.

The Crochet Coral Reef project is a condensation of human labor – particularly female labor – hundreds of thousands of hours of stitching quietly performed.

These artworks reflect the history of handicrafts traditionally done as a means of necessity but now being embraced by the art world as a way of claiming – or rather reclaiming – the aesthetic power of ‘fancywork.’ For of course, handicrafts have always been aesthetic tools rich in symbolism and expressive possibility, and ‘ladies’ doing their embroideries have long been artists, even if they are rarely acknowledged as such.

These crochet reefs are time-laden rejoinders to a culture of doom, quietly asserting, in what Donna Haraway has called this “time of response-ability,” a message of hope. What can we humans do when we work together, not ignoring ecological problems but also not capitulating to fantasies that rescue is around the corner from some sudden technological solution.

These reefs are militantly un-tech. There are no microchips or bit-streams involved. And yet there is technology there, for the crochet hook and its myriad cousins – knitting needles and fishing net hooks among them – are some of humanity’s oldest, most critical technes. By insisting on the value of the hand-made, the Crochet Coral Reef project makes a claim about history and the importance of material labor to prospects for human survival. (See Crochet Codes and Crafty DNA)

And just as living reefs are created by the efforts of billions of tiny coral polyps working together, so the Crochet Coral Reef is constructed by communities, thousands of people working together.

Every crafter who contributes to the project is free to create new species of crochet reef organisms by changing the pattern of stitches or working with novel materials. Over time, a Darwinian landscape of wooly possibility has been brought into being. What started from simple seeds is now an ever-evolving, artifactual, hand-made ‘tree of life.’

Core Collection

There is Core Collection of crocheted reefs created by Christine and Margaret Wertheim that travels to museums and galleries around the world. This collection has been shown internationally, including at the the 2019 Venice Biennale, Andy Warhol Museum (Pittsburgh), Hayward Gallery (London), Museum of Arts and Design (New York), Science Gallery (Dublin), and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History (Washington D.C.) Designed, fabricated, and mostly crocheted by the Wertheims, these sculptures also incorporate exquisite pieces from a curated selection of globally dispersed crafters known as the Core Reef Contributors.

Satellite Reefs

The second aspect of the project is the Satellite Reef program. Here, the Wertheims work with communities around the world to enable citizens to crochet their own local reefs. As of 2024, 52 Satellite Reefs have been constructed: in Chicago, New York, London, Melbourne, Ireland, Latvia, Finland, Germany, the UAE, and elsewhere. More than 25,000 people have participated in creating these citizen-generated art+science installations.

Crochet Codes and a Crafty DNA by Margaret Wertheim

In the Information Age we have been taught to think of coding as a symbolic apparatus aimed at the disembodied mind. However, female crafters have been deploying codes for centuries. As a technology, crochet precedes computing in its use of codes and algorithmic processes to generate programmed outcomes. Indeed, crafts such as crochet, knitting, basketry, and weaving were the original digital technologies – technes created by digits – and it is one of the ironies of the computer age that the ‘digital’ has come to connote disembodiment and divorce from the material domain when the term was derived from our hands. History records this linkage in the punch cards used for early computers that elaborated on a system developed to automate looms. In crafts we continue to witness the power of visual codes and the ability to read, enact, transform, and engage with information via our corporeal beings.

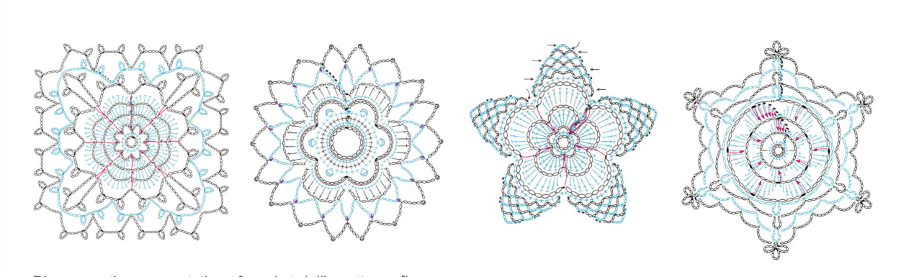

Crochet doilie patterns like the ones below, with their diatom-like graphics, are examples of a spatialized code a crafter can read through her eyes. Each mark or string of symbols represents a set of stitches to be performed, making these images visual algorithms. Beginning at the center and following the code described by gradually spiraling out, the crocheter performs the recipe it describes with her fingers, using yarn as a medium to bring the instructions into material form as a piece of fiber art.

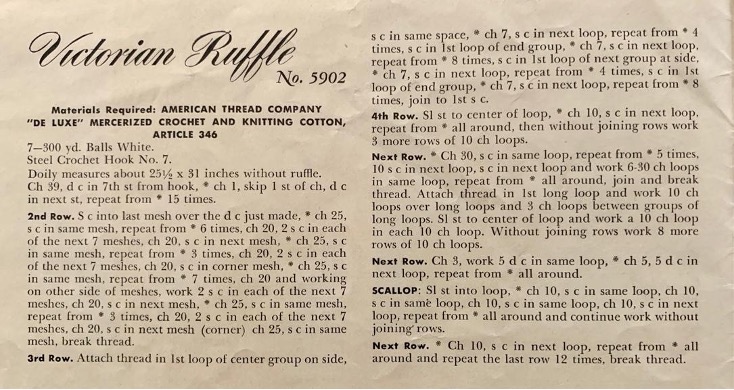

A crafty cryptology is manifest here, for each of these diagrams is an icon conveying structural information about a form to be fabricated in thread. Crochet actually encompasses two distinct kinds of code. In addition to the visual one, is an alphabetic code with each stitch type described by groups of letters – ‘ch’ for ‘chain,’ ‘sc’ for ‘single crochet,’ ‘dc’ for ‘double crochet,’ and so on. This dialect of the digits is another way of representing patterns, as in the image below detailing the pattern for a ruffled doilie.

Alphabetic crochet patterns like this are a craft equivalent of computer programs. Both employ a coded lexicon to indicate specific steps, and both utilize ‘subroutines,’ small programs-within-programs that get called on as repeats. (Such subroutines are indicated in the pattern above by the ‘*’ symbol.) Yet for all the power of alphabetic patterns, the graphic variety has added virtues. In the pattern here, it’s hard to imagine the object being created until it emerges in your hands – who but an expert crafter would recognize the remarkable form in the next image as the result of this code?

With a diagrammatic pattern one knows from the start the configuration it will produce, for the visual graphology presents a one-to-one correspondence with the structural components of the form. Consider the pattern below for a star-shaped doilie. Here, loops represent chains and struts represent single, double, triple, and half-crochet stitches. One grasps from the image the holistic nature of the form being modeled in a way an alphabetic pattern cannot convey.

The science of chemistry, also akin to crochet, has an alphabetic and a graphic mode for describing the structures of molecules and their chemical interactions. Although crochet and chemistry might at first appear very distant subjects – one affiliated with home and hearth, the other evoking antiseptic ‘scientific’ spaces – both activities can be denoted by almost parallel modes of representation, making crochet patterns a near-perfect analog for the language of chemical forms.

A feature shared by chemistry and crochet and by their respective notations is that although all complex arrangements are composed from a finite set of primitives – atoms or stitches – in both realms, clusters of these elements appear again and again as larger stable structures. These units often acquire names of their own. Chemistry has its aromatic rings, its hydroxyl groups, and so on. In crochet, popcorns, piquots, bullions, and bobbles are motifs found in patterns for doilies, edgings, blankets and wedding gowns.

This phenomenon of atomic-clustering also underpins the language or code of DNA. Where digital computers operate on a binary code, DNA’s code is quaternary – so, also, DNA letters group into clusters, this time of three each, called codons. Strings of codons spell out the messages for building the proteins living things are made of. However, if this code was always perfectly reproduced stasis would settle on the Earth, locking life into a groove with no new formations. The virtue of DNA lies in its propensity for imperfect reproduction. When cells holding DNA replicate, malfunctions can occur: here or there a letter is changed. Perhaps one is deleted, or something new gets added in. Such ‘mistakes’ are among the driving factors of evolution, as deviations at the molecular level cause mutations in the physiology of organisms leading to diversity, and ultimately to the taxonomic variety Ernst Haeckel called the “tree of life” – an evocative if controversial phrase. Life, then, is poised at the boundary of continuity and change.

This is where the Crochet Coral Reef recapitulates life on Earth, for we crochet reefers also begin with simple seeds that gradually evolve via deviations into more complex forms. Everyone who comes to the project starts with the kernal of a basic algorithm that generates a perfect ‘hyperbolic’ shape, very much like the ruffled doilie of Figure 3. Crochet ‘n’ stitches, increase one stitch; repeat ad infinitum, is our starting recipe; and by following this process the crafter creates a mathematically accurate hyperbolic surface. Yet these forms – precise, even, symmetrical – are the antithesis of living things, for life is never perfect in the Platonist sense and living things are never quite regular. A move into ‘imperfection’ also sparks the Reef project to ‘life’ hefting it from the domain of geometric precision into a kind of fiberized organicism. Having learned the basic hyperbolic technique, each crafter is free to inject their own deviations; to add to the code, or change it here and there, as occurs in the evolution of living things. We, too, queer the code. ‘Iterate, deviate, innovate’ has been the motto of the project. What is it you can imagine that no one else has done before? Thus, each maker can invent new branches on a crochet ‘tree of life.’ As Earthly organisms accrete variations, so our crochet reef community has accreted a library of pattern formations, bringing into being a wooly taxonomy of crochet coral ‘species.’ Working with codes, we reefers together craft ever-more diverse string figures, generating a simulacrum of both life and evolution that results in a visionary, yarn-based ecology.

Essay excerpted from Value and Transformation of Corals, Museum Frieder Burda, a catalog for the exhibition Margaret and Christine Werthem: Wert und Wandel der Korallen.

Making the Baden-Baden Satellite Reef: A Parallel Universe of Creative Female Energy

By Christine and Margaret Wertheim

From all over Germany packages came flooding through the mail: small ones, large ones, finely wrapped parcels elegantly hand-addressed, and lumpy bundles bursting with life even before they were opened. Inside them all were crocheted corals crafted in every conceivable color, and from a vast array of materials including heavy-gauge hand-spun wool, fine mercerized cottons, synthetic yarns, cut-up plastic bags, and many other fibers both shop-bought and home-improvised. Over six months in late 2021, nearly 40,000 of these crafted creatures found their way to Museum Frieder Burda by hitherto-unimagined migratory paths that brought them from the local region of Baden-Baden; from the cities of Berlin, Frankfurt, Hamburg and Koln; and from tiny villages at the edge of the North Sea and deep within the Black Forest. Some arrived from Switzerland, the Netherlands, Austria, France, Italy, finally from all over Europe, even from Bulgaria, and also from overseas, the USA, Canada and Australia!

This crafty outpouring was the raw material from which the Baden-Baden Satellite Reef was to be constructed, this now-vast archipelago of wooly coral islands displayed in the upper gallery of the museum, and on a giant ‘coral wall’ that evokes both the long history of sewing and quilting bees traditionally performed by women in their homes, and newer histories of monumental fiber sculpture by professional artists such as Faith Ringgold, Sheila Hicks, Nick Cave, Mike Kelley, and Joana Vasconcelos.

More than 4000 people – most of them women – contributed corals for this latest addition to the growing constellation of Satellite Reefs around the world, a globe-enwrapping set of sibling installations that together constitutes one of the largest, most enduring community art happenings ever. During the past 16 years, 50 such reefs have spawned from the original seed of the Crochet Coral Reef we started in our Los Angeles living room in 2005. Emulating the process by which living reefs send out spawn to precipitate the growth of new reefs elsewhere, so our Crochet Reef spawns novel iterations in museums and galleries made by local crafters who come together in collective acts of making to build their own versions of a reef.

If one can trace a biological metaphor here in the mechanism by which crochet reefs replicate, there is also a more metaphysical story to be told, for the Crochet Coral Reef project has opened a kind of portal for channeling creative female energy. When we started our first reef, Christine and I imagined a few dozen crafters might join us in this quixotic entangling of crochet, mathematics, marine biology and environmental reflection. Yet we seem to have generated a wormhole to a vast universe of female craft potential that has to go somewhere. Pouring through the transom has come an exponentiating number of corals, exceeding even our wildest dreams. Over 2000 at the Hayward Gallery in London (2009); 4000 at the Smithsonian in Washington D.C. (2010); 5000 at the Helsinki Biennial (2020/21); now 40,000 in Baden-Baden. We yearn to call the pluripotent zone from which these wonders emerge the Crochetcene, and hail it as a valuable wellspring for future art-production. Indeed, other community craft projects have already been inspired by the methodologies we’ve developed for collective Reef making, including the ‘5000 Poppies’ project in Australia, which ultimately resulted in over 100,000 knitted and crocheted poppies as a tribute to soldiers who died in World War I.

Photo © Institute For Figuring

Community art-making requires not just imagination and skill and many nimble hands, but also what we may call ‘technologies of collaboration.’ As feminist science studies scholar Donna Haraway notes, “nothing makes itself,” and to make collaborative works on a vast scale requires a ‘backstage’ managerial infrastructure and framework to support and sustain the aesthetic work being generated for display. In this sense, making a Satellite Reef is akin to putting on a play. Just as a theatrical performance begins with a script that is given local flavor through the specificities of casting, set-design, costuming, lighting and cultural-setting, so each Satellite Reef is a local enactment of a ‘script’ that lays out a general plan of action to be implemented in each different cultural setting through choices about community outreach, display techniques, reef architecture, color groupings, and so on. Will a local reef extend over low pedestals, or creep up the walls? Will it be arranged by hues – a red section, a blue section, and so on – or by mixing pallets, as was done so well in Helsinki. Each reef becomes an opportunity for a local team to become directors of their own production, thereby inviting citizens to the curatorial table, a place generally reserved in the artworld for a select elite.

For the Baden-Baden installation, Christine travelled early on in the process to work with local ‘reefers’ and museum preparators to help conceive and design the staging as a series of low-slung islands featuring conical protrusions, ‘coral trees’, deep fissures and poles on which are showcased spectacular corals. But so many corals continued to pour in from the Crochetcene zone, and the islands filled faster than they could be built. What to do with the extravagant excess? A plan was conceived to have them fill a wall in the museum using the mass of additional corals as a kind of ‘paint’ to render a gigantic conceptual image of wooly magnitude. This monumental work, made possible by the energies of more than 4000 mainly female ‘reefers’, is also a testimony to the unceasing potential residing in the script of the Crochet Coral Reef project. What might different communities achieve with this collaborative technology? As in nature, there is no end to the possibilities for creative surprise.

Christine and Margaret would like to thank the core curatorial team who helped to develop these woolly masterpieces: Kathrin Dorfner, Martina Schulz, Christina Humpert, Charlotte Reiter, Susan Reiss and Silke Habich as well as the entire team of the Museum’s art workshop and twenty seamstresses. In addition, our admiration goes out to all the thousands of people who contributed corals and the immensity of your work.

This essay is excerpted from the book Value and Transformation of Corals, Museum Frieder Burda (2022), the catalog for an exhibition of the same name.

If you would like to buy Christine and Margaret Wertheim: Value and Transformation of Corals please go to www.artbook.com/9783868326888.html