Location: Vancouver, Canada

I. FRAMING THE PRACTICE

When discussing Canadian works on and about the land I find it valuable to bring forward the special cultural context in which these works arise. Even if an artist does not choose to consciously engage place histories in their work, these infiltrate the work in any case, since we and the work we make can only be where we are. Whether they are bioremedial, Social Sculpture, ephemeral, or image-based, all Ecoart works are about and in places, and human relations within these places. Hence, the ‘voice’ of the place is in the work, whether foregrounded or not.

I would argue that most of contemporary Canadian Ecoart works emerge from, consciously engage with, or are informed by what I will call a culturally ambivalent relationship with place, with the land, and with the indigenous cultures of this place. Many works arise from a desire to understand what a sensitive relationship to these lands and this place might be. This is largely because the dominant culture here is that of settler, which is composed of myriad other cultures, an ever-changing mix where everyone is encouraged to bring their cultural practices along.

This settler culture sits rather uneasily on a many-storied land of other cultural histories that reach back thousands of years. And because Canada remained a colony until the mid 20th century, there has always been a kind of subterranean knowledge here within the dominant culture that ‘home’ is elsewhere. The Quebecois longed for France and French culture; the early Scots and Irish settlers built a culture around a longing for home, even as they cleared the land, logged, mined and sent the best away – sent it ‘home’. In the west, the recent flood of East Asian immigrants still call Hong Kong ‘home’.

Our very presence in this place is still based on the ‘extraction of resources’, on taking apart the land. And since the structures built upon colonial power and empire form the very basis of culture and economy, the lands and waters of this place remain, in practice, primarily ‘resource’, rather than home. Home is relationship, home is belonging – and it is difficult to fully enter into that relationship, to belong, when one is living in a resource, or on the lands of indigenous peoples never surrendered to the Crown. There are no ‘commons’ for Canadian settler culture – there is Crown land and there is Indian land.

There is often a particular feeling or sensibility about Canadian artworks about nature and the land, a kind of deep longing, wistfulness partnered with a strong love of place – like the longing for a forbidden love. We are perhaps still looking for how we can really love this place as our home, and how we can be permitted to do so. In this sense the Canadian experience is a microcosm of the experience of Western culture’s relationship with our environing world. In an accelerated frenzy, the forests are falling around us, the seas emptying. We long to feel ourselves one with the world, belonging, and yet can we hope to be embraced, thinking and acting as we do – we, who are so very complicit in the destruction of home places? If so, what is the sacrifice required and are we ready to make it?

II. PRACTICE — WORKS & ARTIST

While relationship to Place and the land has always figured large in Canadian writing, visual and sound art, ecoart works seem to appear here framed within the context of a broader arts practice, as a single event or short-term research focus, rather than being a basis for an artist’s overall practice. My intention in this section is to visit the diversity of the practice via some specific artists, works and projects. These range from the more traditional visual arts to Social Sculpture works seldom recognised as art. Artist and project websites are listed at the end of this essay

There is a great deal of interesting Canadian photographic work and this ranges from the internationally known Edward Burtynsky’s documenting of industrial practices and ship-breaking, to Nancy Bleck‘s studies of individual ancient cedar trees and documentation of process and projects – for example her Dreaming Forward series with the Squamish Nation.

Photography can be a powerful medium. Burtynsky up front declares his work to be seductive and in this lays a great part of its power to engage rather than allow distance and disconnection. The images draw us right into scenarios, real places and acts in which we are complicit, and in doing so we are faced with the choice to feel guilt, or to choose the responsibility of relationship. Detachment is no longer an option, since the connection through the image has already taken us past that point – we might squirm in our awareness of complicity, but we cannot rest in denial.

Bleck’s Cedar People series presents ancient trees to us as individuals, as they are for the local Coast Salish people. She documents their natural and unnatural demise – the first through Becoming Tumulth, and the latter through showing the results of the clear-cut logging that rages through the old growth forest. She reveals this in the context of the relationship of the Coast Salish to the forest in works like Breach of Protocol and Kahkalhil, Wild Woman of the woods, eating her children.

Amir Ali Alibhai, now Executive Director of the Vancouver based Alliance for Arts & Culture, cites Bleck’s definition of tumulth in his discussions of her work:

It takes 3000 years to make tumulth, the sacred paint that comes from the life- blood of the cedar tree. 1500 for the tree to grow to maturity, and another 1500 years for it to return back to the Earth from where it came. The paint is used for spiritual protection. Source: Alibhai, Amir. Cross Cultural Collaboration and Community Art Practice: an autobiographical examination (2002) https://circle.ubc/bitstream/handle/2429/11212/ubc 2001-002.pdf

Sandra Semchuk’swork has long been about place relations and settler culture, and our ability to be present with the land as community. Her long-time collaboration with her late husband, Rock Cree writer and media artist James Nicholas, explored cultural stories of difference, belonging and community. Among their many works, they collaborated on the symposium and publication Land, Relationship and Community.

Sandra’s video work Bear – In the Absence of Acceptance, asks us what it means to place ourselves outside ‘nature’, and she challenges us to ‘ask ourselves how we come to know wild beings that are around us – and how we come to know ourselves as wild beings’. Sandra’s sense of collaboration in her work is broad, and she named the young female grizzly as well as ‘bear man’ Charlie Russell as collaborators in the making of Bear.

Newfoundland artist Pam Hall also speaks about our relationship to place, the land and the seas in her visual art works. One such project was Just Fish. In 1997, Hall was invited to participate in an interdisciplinary research project examining ethical approaches to the fisheries crisis on Canada’s Atlantic and Pacific coasts. Working with scholars from across the disciplines, participating in discussion groups with stakeholders in Newfoundland and British Columbia, the artist spent three years listening, learning, and stretching her involvement with practicing fishers.

Other Canadian artists working with the human relationship to the natural world include Québecoise artist Dominique Laquerre, Vancouver based Nicole Dextras, and Diana Lynn Thompson on Saltspring Island.

It is impossible to think about Ecoart in Canada without Boreal Art/Nature coming immediately to mind. In their own words: “Boréal Art/Nature, an artistrun centre based in the Laurentian mountains in Quebec, has developed an artistic process based on the urgency to understand and reestablish the relationship between art and nature. Through its activities, Boréal has developed two complementary contexts: nomadic art/nature expeditions in Canada and around the world, generally involving ten to fifteen artists of diverse origins, in expeditions ranging from two to four weeks; and artists’ residencies at the 100acre Art/Nature Centre in the Upper Laurentians in Québec, bringing small groups of two to five artists together, for a period of approximately three weeks, around themes which highlight particular and universal aspects of the nature/culture relationship. Both the expeditions and residencies are the occasion for privileged intercultural and interdisciplinary exchanges, and offer a context for an artistic process that favours creative research, inquiry and risktaking. The results of these activities are presented by means of publications, videos, electronic documents, exhibitions, performances, lectures and workshops.”

For twenty-five years the members of Boréal Art Nature pursued this unique project and vision, until their funding was cut in 2008 and the centre dissolved thereafter. Sadly, the website documenting their work is also gone. A 2005 artist exchange with the Welsh collective ointment – Les Marcheurs des Bois : Walkers of the Woods – is documented here: http://www.ointment.org.uk/marcheur/

Jeane Fabb, a founding member of Boréal has a website which highlights her site-specific practice, including her longtime project Wilderness Women in Black.

Another Canadian artist practicing ephemeral art – much of it performative – with, on and about the land is a young artist based in Vancouver, Charisse Baker. The Red Thread was a series of performances both on the land and in more formal garden and performance spaces. It began in icy winter and traversed the seasons.

In traditions and cultures around the world, a red thread, rope, or string, is a metaphor for connection and love. It’s the red string of fate in China, connecting lovers. In Hinduism it’s tied while resighting Sanskrit mantras. Japan, Tibet, North American First Nations, and Judaism, all have similar metaphors. (Carl) Jung said this was rooted in our memory of being connected to our mother by a ‘red cord’. Sometimes the thread is tied between objects or people. Sometimes it’s worn around the wrist or neck and involved in ceremony. Source: http://charissebaker.com/the_red_thread/index.

Both above images: Charise Baker, “The Red Thread”. photocredit: Yvonne Chew.

It seems that in Canada bioremedial works and a significant percentage of land art projects are undertaken by landscape architects, some of whom are artists as well.

Kelty Myoshi MacKinnon is a landscape architect and artist who has worked on

projects that cross over into Social Sculpture. One example of this would be her proposal to design throughways for coyotes and other non-human urban residents when planning changes within cities and parks.

Indeed, much Ecoart in Canada seems to be not so much about bioremediation as it is about preservation, adaptation, and finding another way of being in the world. Remediation projects seem primarily to be small and local, such as community artist Carmen Rosen’s project to mobilize her neighborhood to clean up Still Creek and its ravine near her home. Carmen and Still Moon Arts now create ritual performance and community celebration in the now cleaned up Still Creek ravine habitat.

The great strength of Canadian Ecoart practice seems to lie in the areas of community practices and conservation/activism – and in what can be more broadly described as Social Sculpture practice.

An early example of this involving collaboration among diverse groups and disciplines was the SongBird project, based in Vancouver. Between 1998 and 2002 I acted as Founding Creative Director for the project, which brought together artists, scientists, landscape architects, community groups, local businesses and government agencies in community forums, performances, school projects, habitat building and awareness events and more. Named after songbirds, whose presence is an indicator of ecosystem stability, the project aimed to build community and awareness of nature within the city and the city within nature.

Another important example from the same time period isUtsam/Witness, which was a ten-year collaboration initiated by artist Nancy Bleck (see above), with mountaineer John Clarke, the Squamish Nation (Coast Salish) and the Roundhouse Arts and Community Centre in Vancouver.

Witness began as a project to stop the clearcut logging of pristine old growth forests in nearby mountain watersheds by International Forest products, a mutinational corporation based in New Zealand. The logging was taking place in traditional Squamish nation lands that had never been ceded to the Crown – an area known to the Crown as TFL (tree farm licence) 38 – while the Squamish people had been silenced in the courts. Other action was needed. A seemingly simple plan of visitor weekend camping trips throughout the summer, coupled with the traditional Squamish ceremony of Witness was the strategy taken. Weekend camping trips took visitors to the heart of the forest, both pristine and already cleared. Visitors took on-site workshops in art practices, learned about traditional plants in the forest and, most importantly, witnessed what was taking place – something usually hidden from public view and awareness.

In 2001, in response to the threatened logging of 1000 year old trees in culturally sensitive areas, the Squamish called upon witnesses to fulfil their role in another part of the ritual, that of texwaya7ni7m, a verification ceremony. Hundreds of witness letters were written on behalf of the Squamish Nation and the old growth forests. These were formally delivered to Interfor by Chiefs and Elders in full regalia. It was the beginning of the end of Interfor cutting in TFL 38, as they agreed to a stay of (logging) roadbuilding while the Squamish developed their own landuse plan for the area. It seemed that the subversive activist ritual of Uts’am/Witness had achieved what years of confrontational protest had not.

Beth Carruthers, Rite Action [2006]

Some of Nancy Bleck’s photo work documenting the Utsam/Witness project can be found on her website in the projects Utsam/Witness & Dreaming Forward and Cedar People.

SongBird, Witness and projects like them remain important since they have left lasting legacies of change, impacting communities, lands, habitat and practices. They also remain important examples of what Social Sculpture aims to do, and as templates, or guides, for future practices.

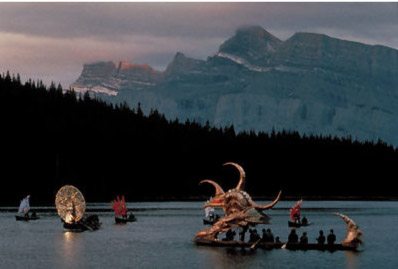

The most recent art and environment project in Canada of which I am aware is the Stanley Park Environmental Art project (SPEA) in Vancouver. Stanley Park is a much beloved 1,000 acre park in Vancouver. A forested peninsula surrounded by sea, it is a refuge for animals both four legged and two legged. When the hurricane force winter storms of 2006 devastated the park, there was outcry from around the world. The storm precipitated two things. The first was a decision by the Park Board to henceforth treat the park as a forest ecosystem, with a goal of supporting the integrity of this ecosystem above conventional park uses. The second was a decision by Jil Weaving, head of arts and culture for the park Board, to create an open call for a juried series of artworks to be installed in the park as a response to the storms and the role of the park in the lives of the people.

The SPEA project is very interesting and I know of no other project quite like it. Unlike traditional sculpture parks, or art in public spaces, these works were created to express relationship with the land, waters, vegetation and creatures of the park habitat. The SPEA project breaks the barriers between nature and culture, insisting that we, and the city itself, are both.

The rules for the artists were that all materials used must be found within the park ecosystem. All materials must break down over time, acted upon by the climate, the creatures – the community that is the park ecosystem. This foregrounds the role of the place itself in the life of the work – the place becomes an active collaborator in the works. Importantly, this is demonstrated continuously to the community as the works change over time.

First, a series of ephemeral works were installed in the park. These were followed by a series of semi-permanent works. The six artists chosen for this project were from both settler and First Nations cultures. They are John Hemsworth, Peter von Tiesenhausen,Shirely Wiebe, Tania Willard, Davide Pan, T’Uy’Tanat Cease Wyss.

There is much to say about this project, and you can find out more by checking the project website (in the list at the end of this essay) and by reading my essay commissioned for the project (available for download from my website). A Flikr photostream is here: http://www.flickr.com/photos/speap/

Often overlooked in consideration of Ecoart practices are theatre, audio, dance, media and film arts. There is rich work here also. In Canada, the work ofR. Murray Schaefer has formed the basis of innovative performative and audio works with environment. To this day, sound artists such as Hildegard Westerkamp (Acoustic Ecology) cite his ongoing influence. In the mid-20Th century he created The World Soundscape Project, dedicated to the study of the relationships between people and their acoustic environment. His And Wolf Shall Inherit the Moon has been described as ‘a curious, hybrid form of theatre, ritual, music, dance – and camping.

Other Canadian sound artists working with environment include composer and musician Lisa Walker who works with interspecies communication, specifically with whale around the north Pacific coast. Leah Hokanson’s Lulu Performing Arts Society on Gabriola Island inaugurated in 2008 The Elements – a Festival of Nature in Performance, one of the most captivating parts of which may have been a work by Andreas Kahre and Darren Copeland in collaboration with a lot of local fish, titled Fish On Air. Underwater microphones placed in the bays around the island captured the sounds of everyday life in the local sea community and broadcast it over local radio channels. Audio can be downloaded from their website.

Osmose and Ephemere are immersive environments, created to explore questions of ecology and engagement by Canadian Char Davies, who is also a principal of the company Softimage. They do not directly engage with land, but with relationships between body and earth, or world. There are a great many works of new media

available for exploration, although I will not do so here. And although both Osmose and Ephemére are not recent works, they continue to be widely discussed.

The plays of Métis playwright Marie Clements are remarkable for their seamless understanding of the world as animate and participatory. Woman become sturgeon, trees speak. This sensibility of the world as an interconnectedness of life comes through even the toughest material. Experiencing her plays performed is to enter into such a world.

The photographs and collaborative dance films of Daniel Conrad on the islands of Haida Gwai reveal also this interconnectedness of being. They foreground the integrity of a place so far untouched by corporate industry, with which we strive to commune. They also remind us of the integrity with this place of the Haida people, who have lived in these islands continuously for some 5,000 years.

The indigenous cultures of the west coast have a rich cultural tradition of what we call art practice. The works that emerge from a culture such as that of the Haida speak about relationship with place and the other peoples – not all of whom are human – with whom the Haida inhabit their home. A few years ago an exhibition of 200 years of Haida art at the Vancouver Art Gallery – Raven Travelling – revealed this rich cultural heritage to the general community. On leaving the exhibition, one found this statement written on the wall of the gallery.

Everything is connected to everything else. These lands and waters have made us who we are, we are deeply interconnected. With the great privilege of this land comes great responsibility. If we fail to care for it, we will lose all that has been born of it.

The art represents this sacred relationship and the centuries of history embedded within it. If the land and the water go uncared for, this art is rendered meaningless to future generations and we will all have suffered an unimaginable loss. Source: Vancouver Art Gallery (2006) Raven Traveling: Two Centuries of Haida Art. exhibition catalogue. Vancouver/Toronto: Douglas MacIntyre.

To watch for

Stay tuned for happenings with ongoing projects and the growth of some large-scale still fledgling projects. One is that of musician David Maggs, an Eastcoast musician known for his work on a project titled Earth To Human. His goal is to create a Centre for the Arts and Ecology in his native Newfoundland. To date, he as secured the land in a greenbelt, along with a heritage church building, and the blessing and support of Canada’s premiere scientist and environmental activist, Dr. David Suzuki.

On the other coast, the relatively new Centre for Arts, Ecology and Agriculture at Foxglove Farm on Saltspring Island offers residential programs. On the same island is based Caffyn Kelley’s Islands Institute, which hosts the online community Art of Engagement. Free to join and participate.

On the prairies, initiated by Rose De Clerck-Floate, a local scientist, the brand new Southern Alberta Science and Art Collective plans to bring scientists and artists together for collaborative projects aimed at tackling some of the considerable environmental issues in Alberta (home of the tar sands, the second largest repository of recoverable oil on the planet after Saudi Arabia).

It seems that although I have been focusing on women practitioners in this overview that the bulk of practitioners in Ecoart are in fact women. It is important also to note that this has not been an exhaustive overview of Ecoart and related practices in Canada, but I think it may be a good start. I want to thank Susan Leibovitz Steinman for asking me to write something on the practice of Ecoart in Canada, which I think remains relatively unknown.

Beth Carruthers www.bethcarruthers.com

Artist and project websites (in no particular order)

Jeane Fabb http://jeanefabb.webgraf.ca

Charisse Baker http://www.charissebaker.com/

Diana Lynn Thompson http://www.dianathompson.net/

SongBird and the Society for Arts & Ecology in Practice www.songbirdproject.ca

Nancy Bleck http://nancybleck.com

Pam Hall http://www.pamhall.ca/about_the_artist/

Dominique Laquerre http://www.dominiquelaquerre.com/

Nicole Dextras http://www.nicoledextras.com

Marten Berkman http://www.martenberkman.com/about/

Some of Haruko Okano’s work http://naturalmanufactured.org/Okano.htm

Carmen Rosen’s Still Moon Arts http://stillmoon.org/

Utsam/Witness archive www.utsam-witness.ca

Islands Institute – Art of Engagement http://islandsinstitute.ning.com/

Southern Alberta Science and Art Collective

http://scienceandartcollective.wordpress.com/

Centre for Arts, Ecology and Agriculture at Foxglove Farm

http://www.foxglovefarmbc.ca/programs/about-the-centre

Stanley Park Environmental Arts http://vancouver.ca/parks/arts/spea/index.htm

Marie Clements http://www.marieclements.ca/

Lulu Performing Arts and The Elements Festival

http://www.luluperformingarts.ca/

Les Marcheurs des Bois : Walkers of the Woods

http://www.ointment.org.uk/marcheur/

Char Davies http://www.immersence.com/

Notes

Copies of Land, Relationship and Community can be found here:

http://www.presentationhousegall.com/bookstore/?item=96

ii Source: Pam Hall’s website http://www.pamhall.ca/about_the_artist

Iii More writing on SongBird can be found in the essay Praxis, which can be downloaded from the ‘writings’ section of my website www.bethcarruthers.com and at the archived SongBird website

Iv Source: Personal conversation with Nancy Bleck, 2001

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 1, CREATING CONNECTIONS

Published August 2010