Location: Leuven, Belgium

I. WHICH FEMINISM

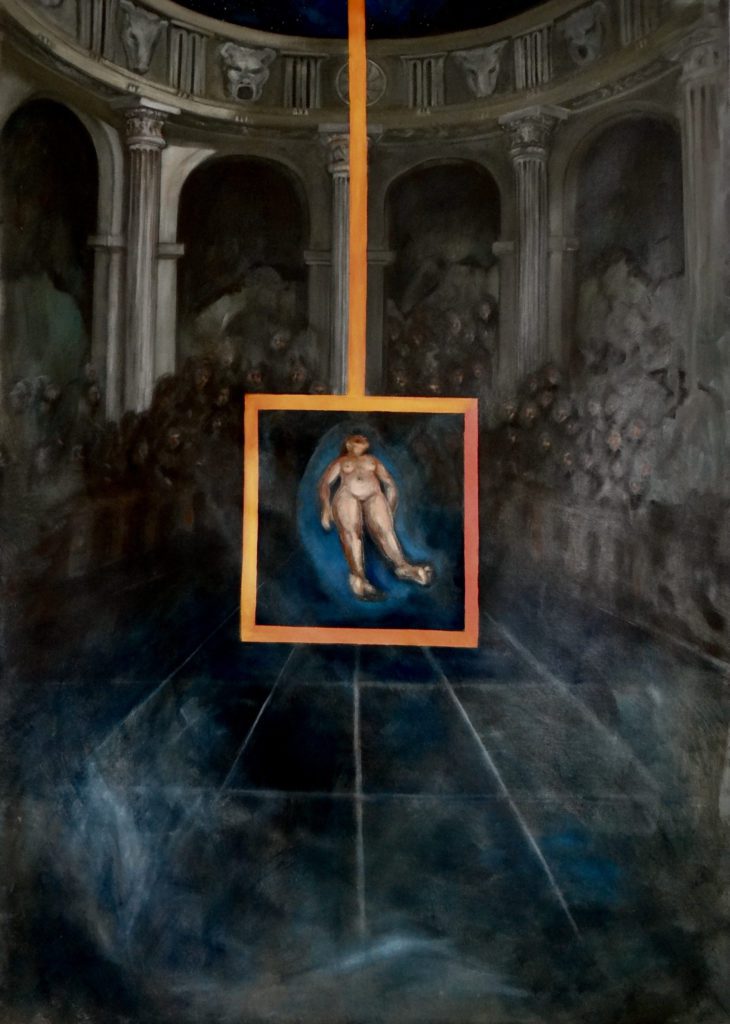

ANDREAS VESALIUS TEACHING THE ANATOMY OF WOMEN, oil on canvas, 35 by 41″, 2020.

IN ART AND FEMINISM, Peggy Phelan defines feminism as the conviction that gender has been, and continues to be, a fundamental category for the organisation of culture, the pattern of that organisation favouring men over women (1). In a talk held at A.I.R. recently (2), Mira Schor adds how new ways of looking at gender, non binary issues are overlaying some of the older problems contested in feminism that still exist today. She sees her work as committing to a civilisational move towards the equality of women, the freedom of women to participate in culture, which seems to be coming and going in culture, a rise of oppression in some countries, a liberation in others. I also follow Griselda Pollock when she argues in Vision and Difference (3): ‘the producer (artist) is formed by the social, economic and ideological conditions of her life; she belongs to certain communities, has particular interests and competences, speaks to and with specifiable groups within large groupings. The work is in part determined by that social locus of production which is quite different from conventional fantasies about the universal voice and visionary powers of genius to transcend the concrete differences in social life. Equally the work addresses not abstract categories – women, the people, the elite or whatever – but a socially produced and placed viewer who must mobilise her own social knowledges and competences or recognise where they do not match with those anticipated by the producer. Instead of confronting a work with the question, ‘What does it mean?’, we might be forced to ask ‘What knowledges do I need to have in order to share in the productivity of this work?’ This becomes crucial for feminist interventions because their difference lies precisely in negating the knowledges and ideologies which are dominant and have become normalised as the common senses about art and artists, about women and societies.’

As a woman in Europe, I strongly believe in women’s rights as human rights. I reject cultural relativism as condoning a status quo, freeing us from making an ethical judgment on certain situations, from taking a stand within the tension between what is and what should be. The way women are objectified angers me, wherever it happens, the way women are reduced to their bodies, denied agency in more or less subtle ways, denied or impeded freedom of movement in the public sphere, threatened with sexual violence, denied opportunities, denied visibility and voice. For me, ideally, feminism is a movement for equal rights in all spheres of life and should be a mutual concern to men and women alike.

As such a feminist activist artist, I source my work from the news media coverage of societal phenomena, policies and systems; such as religion, capitalism and globalism that cause unjust, discriminatory and violent consequences, and then visually process this information from a personal, feminist viewpoint. That is, I’m interested in matters of ethical consequence with respect to health, science, law and leadership in both public and private lives of women. My paintings function as a social commentary from a feminist angle, visually raging for gender equality.

A painting usually starts with a moment of anger and frustration about women experiencing discrimination, sexism, violence which I then channel using a figurative vocabulary into a visual social critique. The painting/image takes shape in my mind simultaneously as I do research for which I turn to literature on social justice, women’s studies in anthropology, gender studies, UN Women annual reports and feminist art theory, a method I also used during my MA of Applied Ethics. Other artists also inspire my practice. For instance, to mention only a few, Nancy Spero (Torture of Women), Leon Golub (Raw Nerve), Ana Mendieta (Silueta Series and Untitled-Rape), Philip Guston (Riding Around). To me, these artists bear witness, in the sense that their work sheds light on phenomena that impact people’s lives unjustly, or violently.

II. #OBJECT! AN ARTISTIC PLAY ON WORDS WITH RESPECT TO THE PORTRAYAL OF WOMEN

I BEGAN TO THINK about the OBJECT! (4) series when our newspaper published a photo about a bombing of Aleppo. A woman ran into the street through a dust cloud grabbing two children, one in each hand. She held an orange coloured blanket that looked very much like a blanket we used to have at our house when I was a child. One of the kids was crying as his mom feverishly dragged him along, his feet not touching the ground, his face bloody. The woman had blood on her face and dust covering her black coat. Her kids’ brightly coloured clothes were an alarming contrast to the cloud of greyish dust; so vibrant and alive. I wondered where they were running, how or even if they would find shelter. Would the mother be able to find food for her kids? What had she left behind? Women in conflict zones rarely get their stories told, yet they are the ones who suffer the greatest impact, experience the most traumas and must find a way to carry on. They usually have no say in the politics of conflict, but must deal with its consequences. They are the ones who muster the most resilience and find the courage to even keep their family going. Those were my thoughts while observing the photograph. I did not want to stay a ‘quiet’ observer and even if I didn’t know the personal story of this particular woman or the outcome, I wanted to make her visible. So, I started painting the OBJECT! works.

The paintings are a counterpart of the way important political events and wars have been painted throughout history to honour and glorify the victors, and male heads of state. Francois Gerard’s painting ‘The Battle of Austerlitz,’ about Napoleon’s feats, and Jacques Louis David’s painting ‘Consecration of the Emperor Napoleon I and Coronation of the Empress Josephine,’ are two works that are exemplary of this long held tradition in art. The canvases are enormous in scale, filled with active battle scenes and soldiers with the emperor overseeing the battlefield. Eugene Delacroix’s ‘Liberty Leading The People,’ regales a bare breasted (!) woman who personifies freedom as she storms forward with the national (!) flag in hand. Believing that the personal is indeed political, I began portraying real women around the globe whose stories are discarded as insignificant. Anthropologic research shows that women in many societies were viewed as prestige goods, ‘prestige,’ because they were/are bearers of life and ‘goods,’ because as a commodity, they could be ‘deployed’ to increase the group’s prestige. It explains why men secure control over the women in a group in patriarchic cultures. Feminist studies in anthropology have focused on the conditions perpetuating the low status of women, across cultures.

My process of working begins with the collection of newspaper clippings and online articles about women’s status in societies around the world. I reflect on how they are portrayed, how they are written or talked about, and how they present themselves if they are allowed independent agency in the public sphere. The result is a personal commentary on these stories; I portray these women and I use the word ‘personal,’ since I cannot deny my own context while doing this work.

The OBJECT! series thus evolved into poster-like paintings of women and girls. Inspired by images and stories found on the web and in written media, these paintings portray ‘real’ women as they are living everyday sexism, inequality, gender-based violence. The title ‘OBJECT!’ is a word play, confronting the media images of women we are bombarded with in Europe or the US, suggesting women must be sexual in order to even be seen. Music and film industry often objectify women in images that are manipulated and reduce them to only their physical bodies. Some of the paintings, conceived as political posters/pamphlets were available online for download to use in the public space all over the world (Posters for Progressives). I also designed a set of postcards from the paintings that I sent out to feminist institutions, clandestinely placed in library books and postcard displays in museum shops I visited for people to find.

Here are some images of the series:

GIRL WITH A BLUE BURQA, Oil on paper, 14,5 by 15′, 2015.

This piece addresses the veiling of women in Afghanistan under the Taliban as a way of hiding them from and denying them agency in the public sphere.

FACE TO FACE, diptych, oil on canvas, 2 panels, each 40 by 53′, 2018.

This painting addresses the EU refugee crisis and how the EU fails to come up with a workable and human solution to address asylum and migration. The painting is a plea for a gendered approach of refugee policies, as displaced and refugee women are more vulnerable along their flight. About the image: it is based on media coverage of how the Italian police and carabinieri detained refugees and migrants around Milan Central Station (May 2018), using police dogs. The image of a fiercely barking dog at the detained refugees and migrants was very confronting to me and I decided to use that as an element in my piece.

III. FEMINISM AND THE BODY

MY MOST RECENT BODY of work, The Anatomy Lesson (5), is a reflection on the way art and science approach the female body and in particular the gender bias in biomedical science. During the lockdowns, I created a series of paintings inspired by sixteenth-century Andreas Vesalius’ anatomy textbook ‘De humani corporis fabrica libri septem’ (6). The works address the incomplete way women’s bodies historically were approached in science, due to traditional beliefs, preconceptions or stereotyping, often serving to legitimise women’s ‘inferior’ social status, leaving women vulnerable in health issues.

While working with this sixteenth-century textbook during the Belgian lockdown, following daily updates on the corona virus spreading around the world, this body of work, paintings of human bodies, was actually timely and relevant, as it points to our corporeal vulnerability. The research that is being set up into why women’s immune system seems to be more effective in fighting the virus than men’s shows the importance of gendered research and thankfully we’ve come a long way since Vesalius.

During my research, I found that in a sixteenth century anatomy book instead of a vagina, only a missing triangle remained from the illustration of a semi dissected woman’s torso (7). In Vesalius’ time, sixteenth-century Christian society, female genitalia were considered taboo. Female flesh was associated with sin and naked women depicted as satan’s servants. Before that, women’s genitalia were thought of as lesser versions of the male organs, turned inside out. The body of work aims to visually bring all those aspects together, addressing that some biases in research methods stretch out over time and compromise the research environment even today, as science journalist Angela Saini (8) describes in her book ‘Inferior.’ This is not only bad for gender equality, or the place of women in science, it’s bad for science and for the understanding of human life itself.’

Here are some of the paintings of the series:

THE ANATOMY LESSON TRIPTYCH, panel 1, oil on canvas, 41 by 59′, 2020.

The first triptych panel is a further development of ‘Pre Existing Condition,’ an #OBJECT! painting about the 2017 controversial Trump Care Bill, aimed at stripping away women’s fundamental rights to control their own bodies and economic futures. The painting turns out to be relevant worldwide today. Just recently, Turkey withdrew from the Istanbul Convention, that was set up to protect women, to prevent, prosecute and eliminate domestic violence. In Europe, abortion rights are frighteningly at stake in some member states. In Poland women protest the new abortion law, nearing a total abortion ban. In Belgium, the revision of the abortion law was dragged into the 2020 federal government formation talks.

PRE EXISTING CONDITION, oil on canvas, 180 by 105 cm (70,9 by 41′), 2020.

The monochromatic diptych, equally titled ‘Pre Existing Condition,’ also organically grew from that first painting and expresses that same idea, as if I’m hammering on the same nail over and over, refusing to let women’s rights infringement issues to ‘drop into the blind spot of culture’ – as Olivia Laing words it in an interview about her book ‘Funny Weather, Art in an Emergency.’ (9)

IV. CHOREOGRAPHY OF PROTEST

IN MY NEXT PROJECT, I will develop a body of work about women’s protest movements, which I would like to approach from a choreographic standpoint, as developed by Susan Leigh Foster (10) in ‘Choreographies of Protest’. My aim is to pictorially express how bodies in protest move and react to each other. I will source my work from historical and current material, such as the Trojan women, the French Revolution Poissardes, the Polish women protesting the new abortion laws, the women’s march, ni una menos in Mexico. Also pictorially, through composition, referring to how in Renaissance painting, time is suggested and simultaneous events depicted, I will explore ways to connect them to the day-to-day experience of women here and now in my context. For inspiration, I’m looking at the political paintings by Leon Golub, Vincent Desiderio, Alice Neel, Cecily Brown. I want to find an answer through the process of painting to questions of composition of such a painting. In particular how the shapes, values and colours can support the narrative and incorporate the time lapses in the dynamic of women’s protests, trying to make the paintings more painterly and yet no less activist than the illustration style I used in my #OBJECT! series.

Here are some draft images I use to start the composition with:

CHOREOGRAPHY OF PROTEST, draft painting based on 19th century asylum photos of hysteria in women, a Valeska Gert Performance and an etching by Francisco Goya in The Disasters of War. Oil on paper, 8 by 12″, 2021.

CHOREOGRAPHY OF PROTEST, draft painting for The Women’s March. Oil on canvas, 23 by 31″, 2021.

V. FEMINIST ACTIVIST PAINTING

MY THINKING ABOUT ART’S functioning in society is consistent with that of authors like Olivia Laing, Siri Hustvedt (11) and philosopher Martha Nussbaum (12). Laing is adamant about the political, activist role art can play in people’s lives. For her, it has to do with art’s capability to conjure feeling. She argues that artworks that take you deeply into the reality of another person’s life are offering itself to the viewer’s empathic capabilities. Laing thus believes in art as a creative, active and generous cultural force through which thinking happens and through which social justice can happen, making art essential to civilisation. Her idea of a ‘reparative reading’ of a work of art resonates with me. At the core of the reparative lies the motivation to make something that ‘gives’ to somebody else that you don’t know and that you might never meet. In other words it can offer compassion, a reasoning Martha Nussbaum expands for literature in that reading, through imagination, can open up our empathic, compassionate capabilities. I agree with these thinkers that art has the potential, as a (latent) emancipating, empathic force to touch people, to open the viewer’s world to other people’s experiences, their suffering, their issues, their reality. And maybe this may lead to other ways of being in the world with each other. I believe it can make us reflect differently on the way things are. These times, bombarded as we are by the news, the social media, images, reports of violence, wars, pandemic etc, it is easy to become numb, to look away, to feel impotent, unable to resist. Art can take the role to help us question the status quo, channel, process, point to blind spots. Maybe this has to do with a ‘viewing space in which time is stilled,’ in which the viewer looks at a painting, a quiet space outside of the turmoil and rushing real time media, as a force to create a different frame of mind.

ENDNOTES

(1) Phelan, Peggy. Survey in Reckitt, Helena. Art and Feminism. London ; New York, NY : Phaidon, 2001.

(2) Mira Schor, Collaboration and Feminism. In Susan Bee, Feminism and Collaboration, Session 3, of [A.I.R. + BATURU] Feminist Art Digital Program. February 8, 2021.

(3) Pollock, Griselda. Vision & Difference – Femininity, Feminism and the Histories of Art. London/New York: Routledge, 1990.

(4) The #OBJECT! works are archived on rveobject.tumblr.com

(5) The Anatomy Lesson works are archived in a viewing room on my site riavandeneynde.studio

(6) Vesalius, Andreas. De humani corporis fabrica libri septem. Basel, 1543.

(7) The book was on display at St. John’s College at Cambridge University, Under The Knife At St John’s: A Medical History Of Disease And Dissection, 25th. March 2017.

(8) Saini, Angela. Inferior. Fourth Estate (May 30, 2017).

(9) Laing, Olivia. Funny Weather, Art in an Emergency. W. W. Norton & Company; 1st edition (May 12, 2020). Interview at the 2020 Edinburgh International Book Festival Online.

(10) Foster, Susan Leigh. Choreographies of Protest, Theatre Journal, Vol. 55, No. 3, Dance (Oct., 2003), pp. 395-412 (18 pages), The Johns Hopkins University Press.

(11) Hustvedt, Siri. Living, Thinking, Looking. Hodder And Stoughton Ltd.; Trade Paperback editie (14 februari 2013) and also A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women. Hodder And Stoughton Ltd.; 1st edition (July 13, 2017).

(12) Nussbaum, Martha. Poetic Justice. The literary Imagination and Public Life. Ballantine Books; 1st edition (April 30, 1997).

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 12, TAKING ACTION

Published October 2021