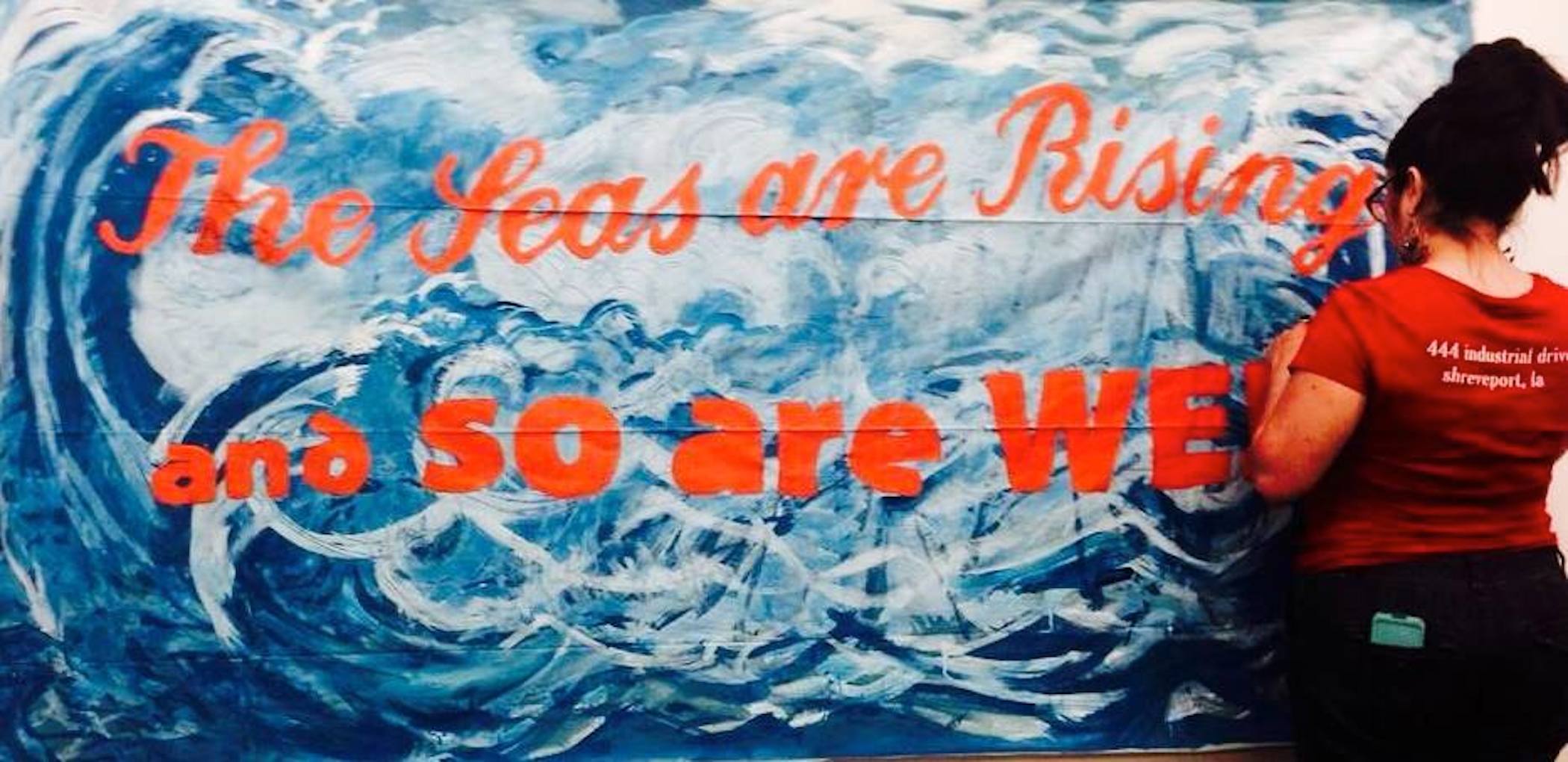

THE SEAS ARE RISING, banner painted for for the Southwest Workers’ Union, Alice Canestaro-Garcia (Pájara), 2015.

Pájara writes ‘I painted the background (the ocean). I was VERY honored that this banner was used at the entrance of the large general assembly tent in historic Congo Square, New Orleans. We gathered for the Southern Movement Assembly which coincided with K10, the 10th Anniversary of the Katrina Hurricane disaster.’

I. INTRODUCTION: STUDYING THE CULTURAL POETICS OF ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

‘RESEARCH, THEN, …IS the road traveled, the image on a wall painting, the impromptu conversation with an elder about an herb that soothes a sore throat. It is reading between the lines of the anthropologist’s interpretation.’ -CherrÃe Moraga1

‘Feminist Visual Poetics of Environmental and Climate Justice’ presents environmental justice artwork from my book-in-process that has a place in an emergent interdisciplinary field that T.V. Reed names ‘Environmental Justice Cultural Studies, part of ecocriticism and eco-feminism.“2

This field also belongs to ‘environmental humanities,’ where, like in much humanities research, study of feminisms’ roles is largely neglected. Greta Gaard, Joni Adamson, and many others (myself included), have conducted related studies of literature, but less research (to my knowledge) focuses on visual art-forms. In presenting visual work, I synthesize critical analysis from public, conceptual, digital and media art theorists as well as from social protest art analysis, public art histories, such as Toward a People’s Art: The Contemporary Mural Movement by Eva Cockcroft, JP Weber, & J Cockcroft3 and iconographies of urban art such as Susan A. Philips Wallbangin’: Graffiti and Gangs in L.A.4. Originating in the interdisciplinary expression of particular ethnic groups, my work shares an approach with Engaged Resistance: American Indian Art, Literature, and Film from Alcatraz to the NMAI by Dean Rader.5

My study utilizes visual concepts such as Rasquachismo from Chicana/o art (Amalia Mesa-Bain and Tomás Ybarra-Frausto) and draws on sustainability concepts such as ‘high performance buildings’ (David Orr), strategies from critical theorists of literature (Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak,) and film (Ella Shohat; Michelle Wallace) visual sociology, anthropology, and women’s resistance studies (Vandana Shiva and Barbara Harlow), particularly in the context of ethnic and third world studies (an area of interdisciplinary coursework and research from my Comparative Literature PhD program). Analysis from postcolonial, feminist/womanist/mujerista theorists offers layered contextual readings based on social identity, place, protest, intersectionalities and the roles of activist aesthetics in transformative images. While I won’t have space to go into most of these aspects in this essay, I mention these names and ideas as recommendations for readers to follow per their own interests.

This essay offers a sampling of the visual artwork presented in Cultural Poetics of Environmental Justice: Blueprints for Climate Justice from Chicanas and Women in India–my interdisciplinary study of a broad spectrum of what I call ‘cultural poetics’–novels to poster art, poetry to murals and other wall art, blogs to brochure and poster graphics, testimonio to philosophy to installation, conceptual, performance and digital arts. This expressive material promotes environmental justice and–I am convinced–is particularly relevant to promoting justice and wellbeing in the wake of climate change. ‘Environmental justice’ is the antithesis of ‘environmental racism’ identified quantitatively by sociological studies and named by activists during protests against toxic invasions when civil rights veterans recognized a déjà vu of earlier racism in the opposition they faced. The environmental justice movement grew strong in the 1980s, but the concept of maintaining environmental justice identifies an older phenomenon that plays a role in the wellbeing, indeed the ‘common good’ of humanity, and of earth, herself.

As a doctoral student in the 1990s, I was introduced to the movement by compañeros involved with cultural expression upholding ‘environmental justice’ in activism and/or scholarship. This discourse exposed ways that environmental racism links to both social domination and environmental degradation. In the 21st Century, artists, activists, and authors, and environmental and social justice and human rights organizations have produced planetary mandates for sustainability that preserve equitable life quality across cultural borders and for future generations in the face of global warming. My book shares wisdom gleaned from the poetics of communities facing environment ills. It shows how strategizing to address climate justice– devising honest, effective and equitable approaches to global warming trends may benefit from previous environmental and social justice work and expressive, artistic/cultural process.

II. VISUAL POETICS OF ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

STAFFORD DUMP MURAL, (left side) Del Rio, TX, (across the Rio Grande/Bravo from Ciudad Acuña, Coahuila); photographed by Women & Gender Studies students, 1999.

CULTURAL POETICS… EXAMINES ICONS and images countering environmental racism and promoting environmental justice through re-presenting self and community, thereby shedding new light on feminist theories of organizing, social identity and structural dominations, and speaking to social identity representations vis-Ã -vis climate chaos. Artwork created by those compelled to expression by environmentally-related disenfranchisement presents cultural mezclas and negotiates border landscapes of ancient and avant-garde activism. Visual artwork takes shape in multiple genres and venues eco-justice art has been screened on UFW and PODER T-shirts, in Indie films at San Antonio’s Cinefestival and the Rio Grande Valley’s CineSol, and in films in production from Bhopal, Madya Pradesh, India to California’s urban gardens and documenting border walls and pesticide plants in the Rio Grande Valley in Texas: examples include The Garden. and Bhopal 84.

Artwork appears on postcards and posters from Bhopal, and in murals in both rural and urban communities. Artists produce images of environmental racism and community resistance showing alliance with environmental justice organizations. Such work includes Marsha Gomez’s sculptural Madre del Mundo series and Ester Hernández’s screen-print satire of the Sun Made Raisin Maiden this time a “Sun Mad” calavera -on-pesticides; a related 2008 print ‘Sun Raid’ takes on U.S. deportations.

In the early 1990s, trans-media performance art included Belinda Acosta’s “Objects in Mirror Are Closer than they Appear,” and “FALSIES and the new way to reclaim information about your/my/our body” and The Corporate Cook’ by Tammy Melody Gómez. As digital art, spoken word and multi-media art proliferated with the proliferation in information technology, issues of environmental and climate justice have been frequently undertaken in new media, but, sadly, for our environmental health, the early pieces remain salient. Tammy Melody Gómez’s current projects can be seen here:

http://blackearthinstitute.org/?staff=tammy-gomez, http://www.hatchfund.org/user/tammygomez.

My study transcends boundaries between what is made to be ‘art’ and what is made to be ‘movement praxis’ and what is a hybrid of the two. A stunning example of the mezcla or mixture is Liliana Wilson’s drawing rendered as an announcement of the Foundation for a Compassionate Society’s program on nuclear exposure and breast cancer.

Liliana Wilson’s drawing for the Breast Cancer and Nuclear Radiation portion of the Breast Cancer and the Environment Conference, Austin, TX, February 19, 1994.

While my essay draws heavily upon street/protest-related artwork and academics that supports that work, the purview of environmental justice poetics extends beyond reaction and includes innovative, proactive stances and the melding of ancient and newfangled wisdoms. Wherever environmental justice visual expression is rendered, that place beckons. Poetry/Art of Witness is important. Recycled and repurposed arts and slow arts and food and food justice movements function as transformative shifts away from devastating effects of all-consuming consumerism and the greed for profit–blinded from other motives that feeds it. My critical work is informed by my own creative process, and visual and poetic work. Environmental art/ installation and performance art is important to me, partly because these are art-forms I engage extensively, as an artist, myself.

Students in my writing, literature and culture, and environmental studies courses have studied the overlapping issues of environmental and climate justice as well. Their assignments ask them to offer primary research and grassroots solutions, often from their own communities, and their projects have contributed to reshaping their universities and civic spaces, and to the work I am sharing. In my classes, we define parameters of study by considering whether and how the ‘Principles of Environmental Justice‘ address the issues we take on). Following these Principles would go a long way toward developing more sustainability on the planet.

STAFFORD DUMP MURAL, (right side) Del Rio, TX, photographed by Women & Gender Studies students, 1999.

In this bordertown mural, women and men, side by side, protest against a waste dump slotted for West Texas. Aspects of “nature” in this mural, locate its bi-national site on the Texas-Coahuila border. Study of the environmental justice poetics of Sierra Blanca, a nuclear waste dump also proposed for a small predominantly Hispanic, West Texas town close to the Mexico border demonstrates that the most successful cultural work against nuclear dumping in this region has been bi-national.

III. FEMINISMS IN THE IMAGE-MAKING

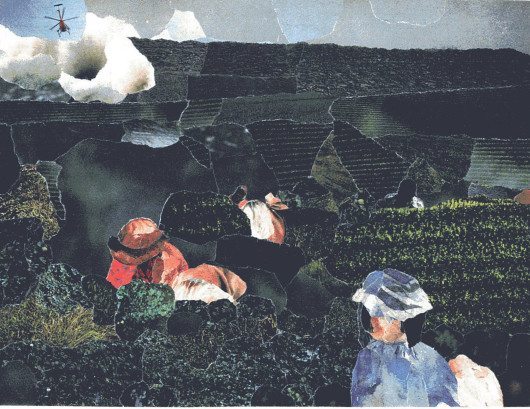

CAROL ANDREAS WAS A FEMINIST sociologist, artist and activist working on multiple fronts throughout her life, who, in her retirement, created torn paper collages to commemorate places and experiences, and to protest injustices. She printed these as notecards, thereby making her art more widely accessible. Here, in league with farmworker unions, she depicts farmworkers working the fields, while a crop duster spraying pesticides approaches, seemingly disregarding them as well as the environment he is contaminating. Andreas’ scholarly work includes the first Women’s Studies textbook, books on women’s luchas (struggles) in Chile and Peru, and a book on the meatpacking industry’s human rights and environmental justice toll.

You can’t really separate issues of ecology from feminism or from human rights or from development, or from issues of ethnic and cultural diversity. – Vandana Shiva6

Focusing on ‘women’s work,’ balances the centering of male-generated work that remains the norm in much of academia and the arts/culture. Feminism extends beyond the defining scope though, as intersectional oppressions on one hand, and the nexus of common interests, on another, link women across boundaries. Social identity, histories, healing strategies, regionalism, language, and the breaking of the western/male binaries between culture and nature tweak conventional interpretations. Guerilla and revolutionary art, artistic commons, community and public art-forms, deliberate, artistic process unencumbered by profit-motives, all contribute distinct facets to this body of work. Feminist interpretations, significant to new fields of digital and movement arts in relation to social change push the envelope on visual media interpretation and criticism, opening public spheres and charting the theoretical groundwork and aesthetics that orient distinctive, new directions taken by work executed under the rubric of environmental justice. Artistic process from a justice standpoint encourages values-in-common honed by groups and artists across the generations and the planet. These ideas all serve a body of work engaged in environmental and climate justice creative expression, and are in line with feminisms articulated worldwide.

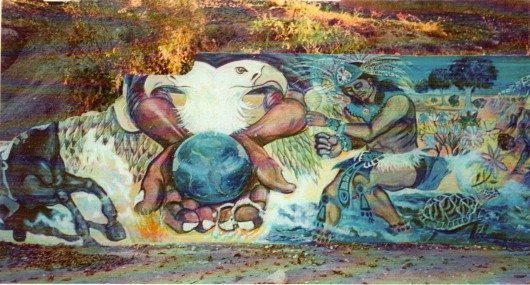

‘Barrio Jungle’ Community Mural Blessing and murals depicting 500 Years of Resistance from Eugene Oregon and El Dia de Agua from northeastern México.

My feminist definition of ‘cultural poetics’ follows interdisciplinary usage to signify the symbolic, aesthetically-considered expression of transformative action that voices a problem, analyzes and addresses it, and proposes a societal change. This poetics generates the foundational concepts and principles of environmental justice around which my study is organized. Overall, feminist, visual texts are informed by experience, and garner both aesthetic and conceptual considerations. Environmental justice is an organizing principle by which essentialist subject positions are deepened through images of differing facets of experience, perspective, belief and expression. The poetics promote synthesis of planetary concerns that can negotiate boundaries and even encourage alliances between marginalized and privileged communities and between academically-empowered and societally-disenfranchised activists and artists.

Aztlán’s herons in the BARRIO JUNGLE mural on San Antonio’s West Side. The woman who conceived and named the mural wanted to paint a ‘beautiful jungle’ of flora and fauna for her neighborhood that was derogatorily called a jungle; such recuperative naming is frequent in environmental justice poetics. Painted by San Anto Cultural Arts, late 1990’s.

IV. IMAGES PROMOTING WOMEN’S ACTIVISM

CHIPKO MOVEMENT MURAL, Kalahandi District, Odisha, India, Development Agency for Poors & Tribal Awakening artists, photographed by Dwight Platt, July, 1994.

…decolonizing ourselves (our communities and bodies) is inherently connected to the decolonization of nature. –Devon Peña7

LIKE TEXAS BORDER COMMUNITIES, Orissan (now Odia) Adavasi communities are among the poorest in their respective countries and yet are suffering at the hands of wealthy, extractive industries, while holding to their own rich, cultural traditions of both immigrant and indigenous cultures. Both regions have also produced environmental justice poetics, such as this Odia mural of women using their embrace and the traditional sacred, protective thread to protect the forests from men with hatchets who have probably been hired by an outside contractor to cut the trees. This mural supports the Chipko Movement, which originated as an anti-deforestation movement in Northern India’s Himalayan foothills and spread, partially through such expressive culture, to other parts of South Asia. This mural’s placement in the east coast state of Orissa, (now Odisha) on the wall of a tribal development and services office in a rural district shows the translatability of environmental justice struggles especially when some cultural symbols remain constant. The tying of a sacred thread around the trees is Hindu symbolism from a protective ritual–performed by daughters who tie a sacred thread around their brothers’ wrists–that has been used in political vigils to save trees. Poetry, song and folktales have been adapted to spread the message, as well.

In much Chicana imagery, too, the woman’s protective role comes out in the mother’s impulse to protect family and environment, especially her children. As Chicana sociologist Mary Pardo has argued, women’s roles in the domestic sphere of family have been transferred to the public sphere of community, as these Latinas work to protect their neighborhoods from environmental intrusion. To see their emblem featuring a mother and child here Mothers of East Los Angeles, San Isabel (MADRES).

They then found their voice, moving on to environmental justice issues–opposing oil pipelines, and using their success to engage with and shape what would now, likely be called “sustainability”: water conservation through hiring youth to install low-water-usage toilets. They preceded Van Jones in connecting environmental and economic success for low income/ communities of color in urban California.

Madres, one branch of Mothers of East L.A. (MELA), the original group, is still active. A recent news article presenting their story quotes one member: Martha Molina-Aviles’ takeaway is that ‘we must take our future into our own hands, to take ownership of our homes against errors that have no boundaries.”8

These words speak to activists most everywhere, and the specifics of the MELA and later Las Madres activism–as they evolved from reaction to issues of community invasion to act upon community and city improvement–is relevant elsewhere, as well. For example, they appear in the film Cadillac Desert9 discussing their experience encouraging conservation and preservation of Mono Lake, which speaks to current South Texas water struggles, though no such Tejana activist group, exists, per se. From MADRES’ engagement in conservation, they saw the folly of piping more water in and destroying rural water tables. They continue field trips to Mono Lake so city youth see the relationships and make environmental connections beyond their homes. MADRES bridges urban-rural and ecological-cultural concerns in their assessments and expressive culture, their stands on water piping issues, and in their corresponding actions, even as they hold to their identity as mothers.

V. MISREPRESENTATIONS REVEALED

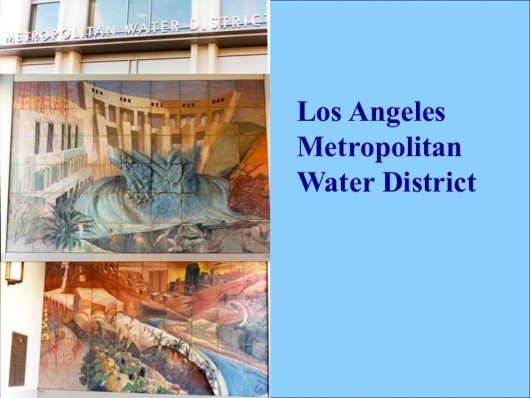

LAS MADRES’ FEMINIST OBSERVATIONS reveal a very different perspective than what is subtly portrayed in the LA Metropolitan Water District’s ceramic relief mural. The vegetable garden portrayed in the foreground is exactly what was lost for the rural communities where L.A. water was piped out.

Metropolitan Water District Bldg. Ceramic Relief Mural, Los Angeles, CA photographed by Kamala Platt, 2001.

Such ironic misrepresentations by government when they are not looking out for the best interest of their constituencies and/or by industry bent on maximization of profits abound; sometimes, environmental justice poetics counters or co-opts these images. As researchers looking for visual evidence of borderland, ecological and social justice poetics, my colleague and I were in Monterrey, Nuevo Leon traffic and industrial smog when we spotted the following billboard advertising eye drops to use against air contamination; the politicized irony of the blue eyes representing ‘purity’ in an area where European-based colonization represents both past and present struggles was not lost on us. Environmental and climate justice poetics counters such perversions with various artistic strategies of expression and argumentation.

Contaminación billboard, Monterrey, Nuevo León, México, October, 1998, Photographed by Irasema Coronado.

VI. WORKING THE EARTH, TOXINS AND T-SHIRTS

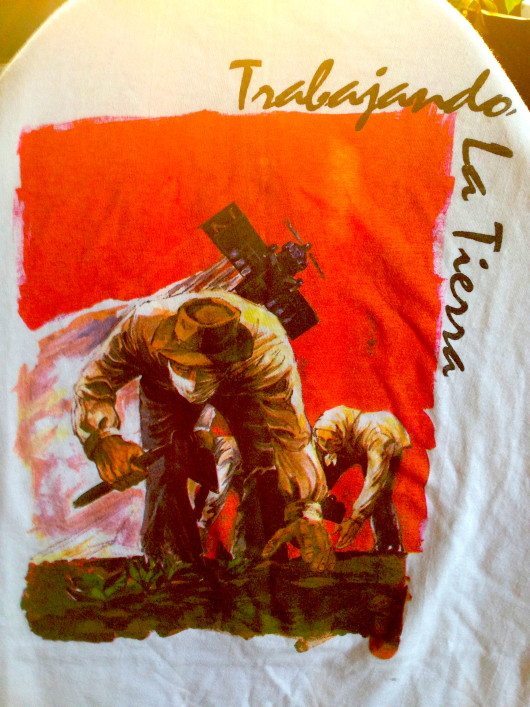

Like in Andreas’ collage in the painted image on the Trabajando La Tierra T-shirt workers are disregarded by the crop duster spraying overhead. The red of the sky possibly represents both the blood spilt under such toxic conditions, but also perhaps the red of communal workers struggle–worker’s rights

IN WINTER 1993-94, THE AUSTIN TEXAS-based environmental justice organization People Organized in Defense of the Earth and her Resources (PODER) produced a T-shirt that proclaims, “As people of color, we must redefine environmental issues as social and economic justice issues, and collectively set our own agenda to address these concerns as basic human rights.” In creating this shirt PODER transposed a part of its mission statement into an expressive form of popular culture and created a means of transmitting a message of social transformation across classes and generational and ethnic boundaries

PODER’s T-shirt suggests that at the crux of “environmental justice” is the act–initiated by people of color in the U.S.–of expressively revising definitions. As the popular form of dissemination of this social message marks distinct complexities at turn of the century, so the message issues in a burgeoning demand for social revision of power from grassroots communities of color. Thus, at the nexus of environmental and social justice concerns is the reworking of social institutions and relationships; this process is, by definition, transformative in its praxis and its theory. And it is a process that leaves in its wake, expressive culture sculpted by the context and conveyor, as well as the content.

The front of the PODER mission statement T-shirt sports a globe, suggesting that the planet is at stake in their struggle as is the universal importance of promoting environmental justice–and now climate justice. Artwork on T-shirts is an important means of communicating environmental justice messages. On the front of another PODER T-shirt from the 1990s is a black and white photograph of three young children from Govalle, the East Austin neighborhood that contained an oil tank farm with facilities belonging to several oil companies that expanded in the midst of schools and homes. The shirt reads simply “Save the Children Close the Toxic Tank Farm.” The tank farm t-shirt’s message “save the children” reminiscent of MELA/MADRES maternal concern is common in Chican@ ecojustice poetics, suggesting that one of the most consistent concerns for these environmental justice practitioners is an ecologically healthy environment for the upcoming generation. For further views (including poetics discussed above) of PODER, check out these resources PODER: People Organized in Defense of the Earth and her Resources and the video Poder.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ziOISV3uZ-I

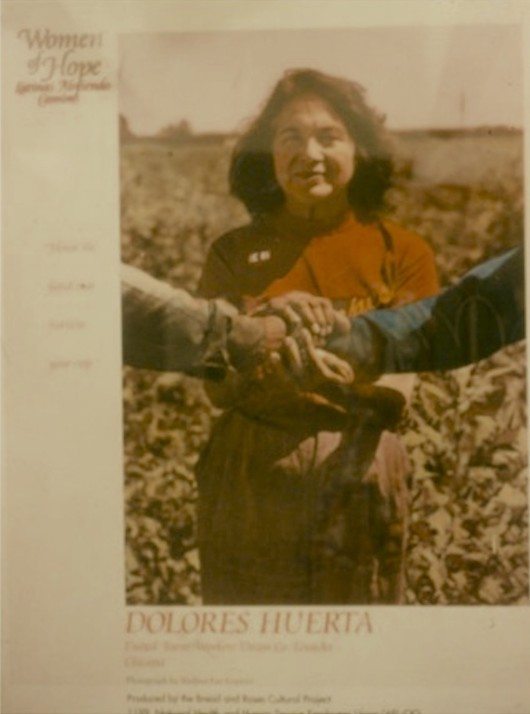

While never having received the monumental status of her United Farm Worker (UFW) union co-founder Cesar Chavez (a fact begging an extensive gender analysis) Dolores Huerta, long time United Farm Workers vice president, is now a familiar name in progressive circles. She has become a female icon of the movement and is demonstrated eloquently in Carmen Moreno’s “Corrido de Dolores Huerta #39” recorded on Los Lobos’ Si Se Puede! (1976); the song connects Huerta’s identity as a woman to her successful contribution to la causa.” In subsequent decades, Huerta has maintained and even expanded her activism, even currently, as an octogenarian.

In the mid 1990s, her photo appeared on a marquee poster in the New York subway system, among twelve Latinas pictured on the Bread and Roses Cultural Project Inc.’s Latina Women of Hope series. Like women in the Narmada and Bhopal demonstrations (as well as Black women in 2015 such as Sandra Bland involved with Black Lives Matter), Dolores Huerta has suffered at the hands of the police. In fact, the police beating of Dolores Huerta in San Francisco was one of the 1988 events which brought “growing visibility to the United Farm Workers’ grape boycott in protest against pesticide poisoning” 10 in response to which, Cherríe Moraga wrote the play Heroes and Saints. The other events that influenced the play’s inception were Cesar Chavez’ 36-day fast, to stop growers’ pesticide ab/use and the “cancer cluster” in McFarland, California.

Of all the issues generating cultural poetics, the largest body of visual work I’ve looked at comes from the survivors of the Union Carbide Co.’s Bhopal Pesticide plant gas explosion in December of 1984. Thirty years later, people continue to suffer, protest, and express their rage–in visual, audible and written discourse–at the environmental injustices dealt by both company and government. For exposure to the history of the continuing debacle of Union Carbide Corporation and government and other bureaucracies in Bhopal, through the expressive culture, see the International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal as well as the links mentioned above. The cover photo of Surviving Bhopal: Dancing Bodies, Written Texts, and Oral Testimonials of Industrial Disaster… by Suroopa Mukherjee, portrays a group of women with placards in a protest march. The book, like the cover, stands out from much of the Bhopal discourse in that it focuses on women’s oral histories of their experience during and following the UCC gas release.11 Foundational to these struggles, unacknowledged women’s contributions can be recovered when we look to visual poetics.

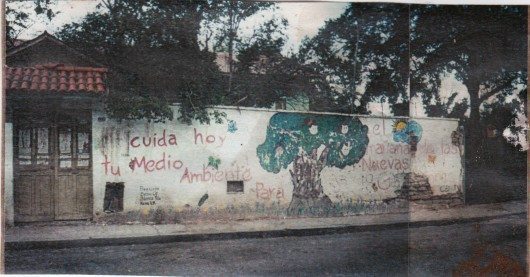

VII. CONCLUSIONS: WE ARE RISING

THIS MURAL ON THE MEXICAN side of the borderlands advocates caring for the environment today for the sake of new generations. In our late 1990s cross border research in south Texas and northeastern México, we found more environmental concern being nurtured among children, often by women school teachers, on the Mexican side of the border than on the US side. As suffering from environmental disaster and unequal protection passes down from generation to generation in places like Bhopal, MP and Mission, Texas, and as global warming-related crises and calamities increase, often in areas already hit by environmental injustices, visual reminders of our responsibilities across the planet and across the generations may be among the harbingers of a necessary and welcome shift in consciousness among upcoming generations in league with environmental justice artists of all ages.

Koiobori In conjunction with a street corner installation, Pájara created, March 2013, as part of San Antonio’s International Women’s Day March.

Pájara wrote: ‘Koinobori (carp-shaped wind socks) have become a symbol of the end of Japanese nuclear power that Energia Mia [My Energy: SA-based group against proliferating nuclear energy] has adopted in solidarity to send the same message to our local utilities…Two years after the nuclear plant meltdowns at Fukushima Daiichi, Japan, March 11, 2011 (our time), Japanese women are demanding that all nuclear power plants be closed. The nuclear disaster is still unfolding, and tens of thousands of people have permanently lost their homes, businesses and land because of it.

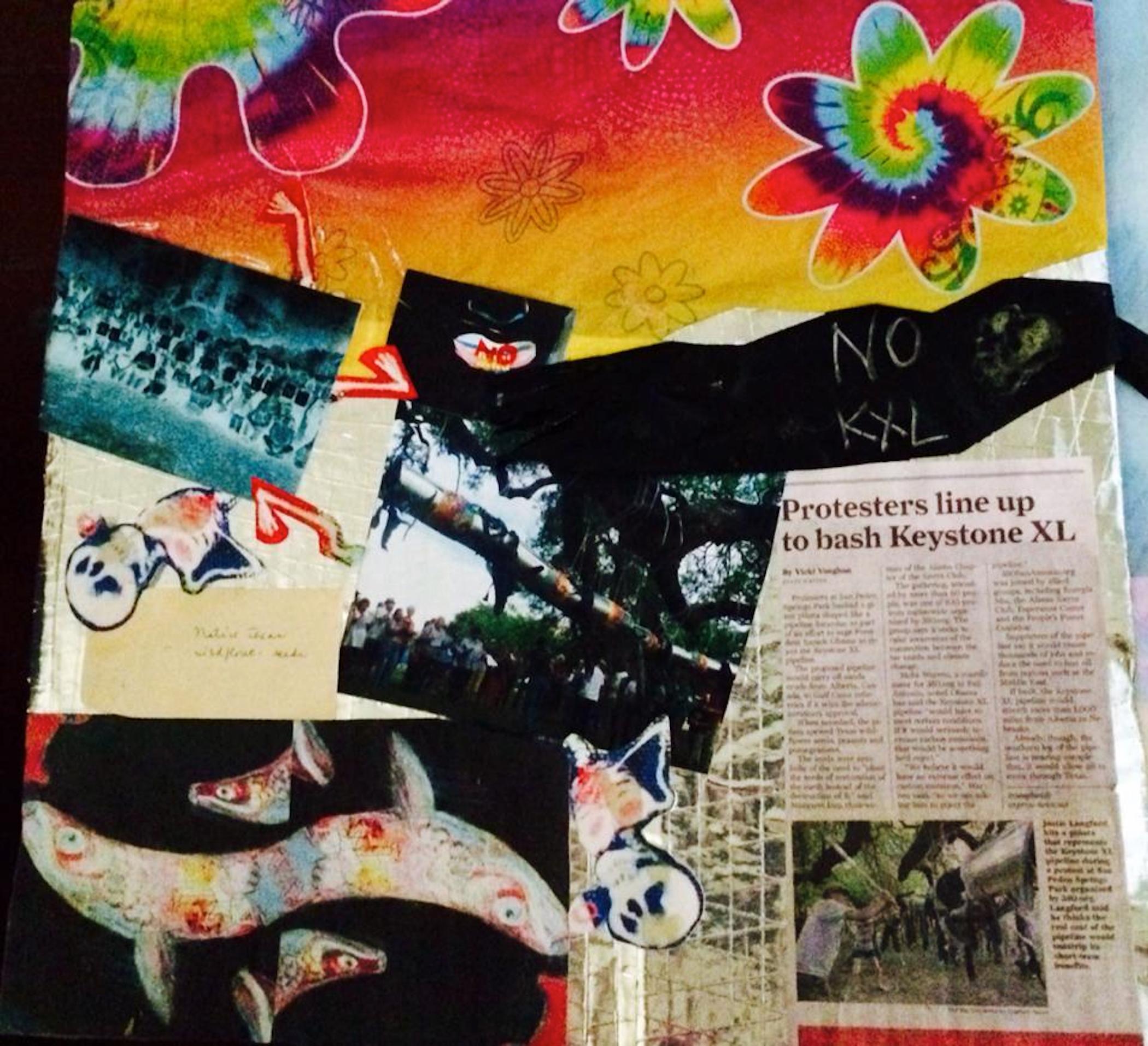

Pájara’s collage was exhibited in HOT!, an exhibit, panel, readings, anthology and film series in San Antonio, TX in 2014; this section includes an image of her Keystone Pipeline Piñata, hung for 350.org demonstration in San Pedro Park.

Other works can be seen here.

The final images, like the first banner, are from Pájara; they stand in for a mezcla of visual, written and performance work, predominantly by women in San Antonio, TX, that engage environmental and climate justice issues–from the cradle to grave aspects of nuclear energy that threaten Indigenous and other communities to fossil fuel extraction that surrounds and impacts the city in multiple ways, to struggles over water, land and other resources, to gentrification, to genetic modification of corn, a plant that traditionally feeds our souls as well as bodies, and shapes our stories and our legacies. This work is found in gallery and street corner installations and performances, on walls, between the covers of books, in digital image, and more. We are indeed rising.

END NOTES

1 A Xicana Codex of Changing Consciousness: Writings, 2000-2010 (Duke University Press, Durham & London, 2011) p. 206.

2 See The Art of Protest: Culture and Activism from the Civil Rights Movement to the Streets of Seattle, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, 2005 Chapter Eight p 218-239.

3 Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1977, 1998

4 Chicago & London: The University of Chicago, 1999

5 Engaged Resistance: American Indian Art, Literature, and Film from Alcatraz to the NMAI by Dean Rader, Austin TX: UT Press, 2011.

6 India Progressive Action Group Newsletter

7 Chicano Culture, Ecology, Politics: Subversive Kin. Tucson, AZ: Univ. of Ariz. Press, 1998. 13.

8 Stephen A. Nuñoz, ‘Politics Starts Locally: The Legacy of The ‘Mothers of East L.A.’ Nightly News With Lester Holt, News Hispanic Heritage Month, September 25, 2014

9 Cadillac Desert: Water and the Transformation of Nature (Part 4),1997

10 Moraga, Cherríe. Heroes and Saints & Other Plays. Albuquerque, NM: West End Press, 1994. 89.

11 Suroopa Mukherjee, Surviving Bhopal: Dancing Bodies, Written Texts, and Oral Testimonials of Industrial Disaster (NY, NY: Palgrave MacMillan, 2010). See https://books.google.com/books?id=KGoIBgAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.