INTRODUCTION

TEN YEARS AFTER CHERNOBYL, IN 1996, reports by NGOs on the aftermath of the disaster were prepared for TV and other media, but the only data released was from the IAEA (International Atomic Energy Agency) together with WHO (World Health Organization)—a report stating that the fifteen firemen who became heroes had died. At this time we showed a video by Russian scientists, it was during our exhibition Reflexion Chernobyl, and it estimated that about one million ‘Rem deaths’ resulted directly from this disaster. Only last year, with the Fukushima meltdown, did these reports of Chernobyl appear in the media. The revelations may have contributed to Germany’s sudden decision to phase out nuclear power.

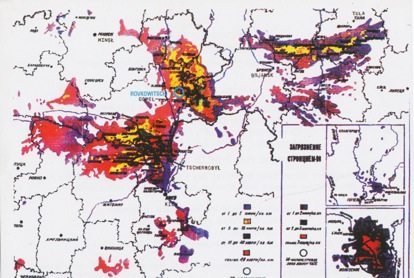

The Chernobyl cloud, composed of plutonium and carbon dust, blew from Ukraine in the direction of Moscow. It was artificially rained down by the Russians in the rural area of Belarus, when people were celebrating their traditional May 1st festivities in 1986. Therefore 70% of the fallout came down in Belarus.

I. ART EXPEDITION TO THE CHERNOBYL ZONE

Map of the Chernobyl Zone with the hot spots of radiation, Humanitarian Association Minsk Archive, 1995.

WHEN TWO ARTISTS FROM MINSK VISITED me at my studio in North Germany in 1995 I saw the map of the Chernobyl Zone and this graphic was very touching: its extension in Europe, the fact that there was much fallout in the hot spots of Belarus at the border to Ukraine, and that the hot spots spread over Germany was frightening. One cannot hear it, one cannot smell it, one cannot see it, but one can feel it in the missing landscape, a lost home, a lost garden, a lost school a lost friend a lost child. This was my impression when I visited the Chernobyl Zone the same year in 1995, together with an artist friend from Sweden. Going there we were accompanied by the secret agency. We found out about this later.

My friend told me that the samples of jam from Lulea at the border of Russia were contaminated before Chernobyl, due to nuclear atomic tests and storage of used fuel rods in the fifties.

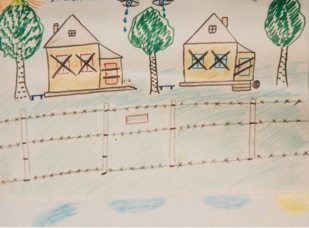

In the Chernobyl Zone in Belarus, where I returned one year later with six other artists, we learned that the people in the village of Rowkowitschi that we visited originally believed they were in the evacuation zone 130 km from the nuclear plant in Pripjat. Later they found out that they lived in the middle of a hot spot. The people there had no legal right to leave the area and join the evacuation quarter of Minsk, an area in which they had built these typical eastern prefabricated buildings, made with concrete slabs, looking more like stacked cartons, stashing contaminated people of a lost landscape— their homes and basis of existence. People, especially children from Rowkowitschi, were dreaming of the evacuation quarter of Minsk as a better place to live, but the children of the nuclear ghetto of Minsk, dreamed of their typical Russian wooden—now empty and gutted—houses with their overgrown gardens. They learned that their empty houses were impossible to burn down because it would concentrate the radioactive contamination even more.

During our artistic expedition—a social and art intervention—we were somehow lucky to be there in winter, and with my Geiger counter it was obvious that the snow was covering the contamination (over 200 mSv) from the ground. But when we were hosted by the families in Rowkowitschi we learned about their permanent problem of contaminated food. In the collapsed infrastructure the people continued to eat homemade bottled mushrooms, potatoes, onions, tomatoes, local bacon and birch sap. When exposed to their food my Geiger counter was dancing. Their universal remedy against radiation is pure alcohol – vodka. They dispute whether the high rate of birth defects comes more from alcohol or from the contamination.

The most efficient human care, which is still organized by the association for The Children of Chernobyl in the EU, is frequented by a constant exchange of families, especially on holidays outside the Zone. A few weeks per year children are offered healing from the ingestion of radioactive food. This work has become increasingly more difficult because of the political isolation of Belarus. The oppressive totalitarian regime was opposed to humanitarian aid. The local NGOs finally had to flee from Belarus and work in exile. But recently the actions of the atomic global legacy on the ‘wall of silence,’ for which Irena Gruschewaja, president of the association of the children of Chernobyl Minsk became an icon, have brought results. They cover the reactor with concrete, wash away contaminated earth and cover again with tar, wash the houses and cars, keep children inside the houses 12 hours a day for several years, and serve alcohol and sauna as a therapy to wash out potential plutonium from the body. The atomic chair has also been introduced, in which the inhabitants can measure their own contamination.

II. ART REACTIONS AND INTERVENTIONS

WHEN I CAME HOME I NEEDED TO PROCEED with my impressions. I painted a kind of map with the colors of that map showing the hot spots as an abstraction. I covered these five paintings with lead and engraved all the information that I gathered from the people I met at in the Zone. I framed these five paintings in a cross shaped heavy metal construction. I colored them the typical blue of the churches and the iron graves of the Soviet culture in Belarus. The entire form then was again filled with concrete. The art piece could only be transported with a tractor. In my neighborhood it became a symbol, a warning sign of landscape but at the same time a memorial to a missing human ecotope.

Just now the EU is paying an enormous amount of money to recover the protective coat of the buried reactor, because it has already burst from the constant radiation. The landscape in contrast became kind of a utopia of wild life again; even now it is used to supply wood for the lumber market. The missing landscape now comes back to us probably fuming in our smokestacks.

Viewing the surroundings of the school in 1996, which became our art intervention basement for one week, we saw the washed out earth and dismal atmosphere of a half filled classroom, with a teacher and his outdated teaching material. In the few days that we were there it was not easy to find artists from Belarus who had the courage to travel in the contaminated Zone. We did find Vladimir Gontscharuk, a very peaceful Russian soul, who was calmly packing his feelings about the situation into poetic paintings, and who was reflecting our actions with several very deep philosophical interpretations like: ‘If the ship of our civilization is the Titanic, then we leave the Noah´s Arc to our children.’

III. ARTISTS FROM AROUND THE WORLD HELP THE PEOPLE OF CHERNOBYL

BOUDEWIJN PAYENS FROM THE NETHERLANDS is an artist with a high capacity of floating into situations and creating unsuspected and spontaneous collaborative performances. He also works as a coach.

He built a boat that encompassed the scholars of Rowkowitschi and snow. It became a depth symbol of the intervention. Payens said:

The inhabitants of the area need to internalize a metaphoric resistance. They need to resist with the continuity of their culture. As artists we could not stimulate help but commiseration.

Since the first publication of the Chernobyl accident, Elvira Reith, a German artist from Cologne, carried out her annual performance in front of the Cathedrals in Cologne and Paris with a robe and a mask: ‘ Sallying may-green in a landscape, a nature, which has lost its innocence.’ She had a very personal reason to address the accident, she, like many other women who had given birth to a handicapped child. With her collaborative and curative power our project found several follow-up presentations in TV and Radio.

The Indonesian artist and political curator Jay Koh joined our action with an inner need to find out the real experience of the inhabitants, especially ten-year old children, who have been born with birth defects. In the interviews that he made with the people about memories and wishes, the respondents were asked to wear a red sleeping bag. ‘In their answers they mourned the loss of friends and relatives either because they moved out of the area or died.’

Peter Sebastian Lange has been an anti-nuclear demonstrator since his youth. An artist and a farmer, he lives a double role, and does not like to mix up art with politics. However, when the congress Ten Years After Chernobyl excluded some of the speakers on our art interaction in Minsk, he changed his mind. His contribution became the most political one of our art interaction. His contribution to our project, called The World Newspaper Rowkowitschi, had the inhabitants of the town fax their thoughts to us for publication on the internet.

At first, they were hesitant to participate, but the on-line model we smuggled in gave them more privacy. Later the artist founded the first Internet Cafe in the evacuation quarter of Minsk, which was confiscated shortly afterwards.

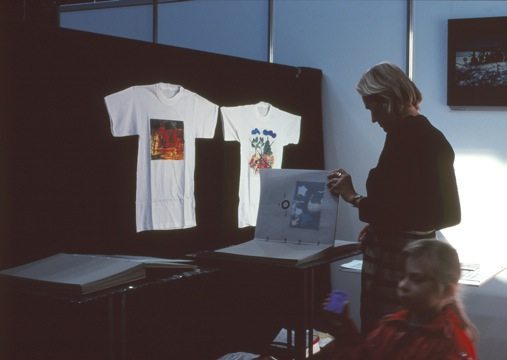

My own contributions during this three year period were continually rejected in both Germany and Belarus, and I had to learn to overcome governmental blockades. The Children´s T-Shirt edition with remarkable motifs about their lost homes served as a permanent memory tool, sold by the NGOs. Organized follow up exhibitions and film events about the reality around Chernobyl included other artists like the photographer Johann-Peter Eickhorst, who accompanied us in our travels.

We finally produced a small book, Reflexion Tschernobyl. It provides a remarkable list of demonstrations about Chernobyl, which exploded first in the West and later increased in Belarus after 1992 when demonstrations in the West were becoming infrequent.

IV. FUKUSHIMA

IN OCTOBER 2011 I VISITED SOUTH KOREA, which believes itself to be far from the atomic spots from Japan. In an exhibition in Daejeon I saw a video contribution by Ichimura Misako – a desperate happening in which the artist was digging in the sealed ground of Tokyo City, expressing the pain of the hopeless action to break the pavement—suffering sweating, crying in the empty street in the yellow light of the night until finally she could remove a single paving block. She continued digging with the lonely pain and suffering as a personal protest of the hidden reality of Fukushima’s nuclear accident. The contrast between the indifference of the atomic authority and the emotion of artistic contemplation on the atomic legacy cannot be more extreme.

V. SOCIAL LAND ART

WITH THE WORK THAT WE DID IN BELARUS and with my colleagues and I arrived at the term ‘social land art.” It means that one considers the earth including the anthropological and ecological memory of land, we use this to reflect on our own existence and act for a viable future. This kind of art is dealing with a delicate responsibility to find the right moment and intensity to be balanced between propinquity to deep concerns of the people in the location and the ability to step back and analyze the situation. The NGO network of The Children of Chernobyl also became a channel for humanity after Fukushima. Art cannot be stronger than this resistance movement. Art can visualize the analogy of the denial that cannot be more obvious in the comparison of the coherences after Chernobyl and after Fukushima.

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 5, ATOMIC LEGACY ART

Published August 2012