Location: New Mexico, USA

I. WHEN THE ISSUE IS SURVIVAL

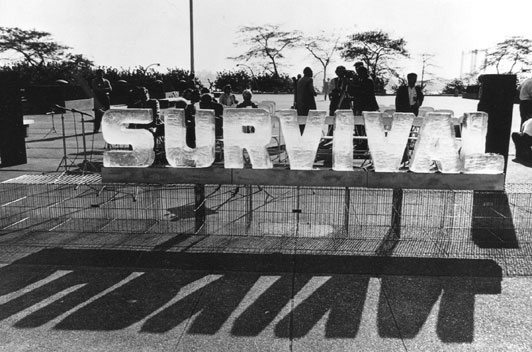

MY INTEREST IN WATER AS AN ESSENTIAL RESOURCE and as a transformational material – from solid to liquid to vapor – has been longstanding. My 1982 United Nations project, titled Waters of the Nations/Messages from the World, was in honor of the United Nations Water Decade to achieve pure water and sanitation throughout the world. The centerpiece of the art project was the temporary installation of an eight-letter word sculpture—a dimensional poem carved of ice—which spelled SURVIVAL. Designed for two related bicoastal United Nations sites the ceremony began with a release of hundreds of racing birds at the United Nations Plaza in San Francisco CA as the opening event of the International Sculpture Conference on August 6, 1982. Four of the messenger birds began a cross-country relay bearing World War II message capsules with microfilmed messages from artists, ambassadors, and scientists of conservation and international peace. They arrived at the United Nations Plaza in New York for a public ceremony on Wednesday, October 20, 1982. The sculptures contained samples of water collected from more than 95 of the then 167 nations of the world, collected with the patronage of UNESCO.

The United Nations certainly did not reach their goal, and now, with more nations, greater populations and greater need, the years 2005 to 2015 have been declared a new UN decade, that of ‘Water for Life,’ with the more modest goals of potable water and adequate sanitation for the world.

Water is a primary issue in New Mexico. Because the Rio Grande river water is essential for the survival of the Las Cruces area and a good part of the state and the region, it was the focus of a two-year research project culminating in an exhibition in the Art Gallery at New Mexico State University. The river was the central image, subject and metaphor. We can live without food for some time but we cannot live without water.

Because of this project I have been introduced to the significant water studies and desalinization programs being conducted at New Mexico State University (NMSU) through the expertise of the Engineering and other departments. My primary collaborator, Phillip King, was the engaging and informed leader of our journeys to the Rio Grande. He is a Professor of Civil Engineering at NMSU and an expert on surface water issues and the hydrology of the Rio Grande, having designed some of its operating systems. To understand the Rio Grande and its significance is to touch on disciplines of history, geology, sociology, national and international treaties, agreements and contracts, engineering, hydrology and particularly issues of ecology and the environment.

II. EVOLVING RIVER

BEING BORN OF WATER AND COMPOSED OF WATER, our own human chemical composition is nearly that of the ocean, of the river. The genesis and history of the river evokes the birth and evolution of our planet earth.

The Rio Grande began many thousands of years ago, in what is now Colorado’s San Luis Valley, as a rocky mountain stream. It was fed by springs at twelve thousand feet, which flowed in a canyon through snowfields and alpine mountain meadows, through forests of aspen, spruce and fir. Its flow is southeast and south one hundred seventy five miles, still southerly, then four hundred and seventy miles across terrain that became New Mexico. Could we have conceived its flow as southeasterly between what became Texas and Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo Leon and Tamaulipas, flowing almost two thousand miles? Once having discovered it did we imagine the river to always be there? And what was it in our history to make us think it was ours to divide and possess?

The stream became a river, wandering, migrating, meandering, braided and sinuous, across an ancient floodplain perhaps four miles wide, for hundreds into thousands of years, leaving sediments, creating oxbows, stopping long enough to generate riparian eco-systems, native cottonwoods, inviting wild migrating birds in its unpredictable path, inviting settlements, grateful for fertile soil until subject to the inevitable floods that could renew or disperse them. Along its banks, over time, was a mixed history of native tribes, scalp hunters, Comanche raiders, Spanish missionaries, Mexican revolutionaries, and even a penal colony.

III. OF TIME AND TERRAIN

IT WAS MILLIONS OF YEARS FOR THIS MIDDLE RIVER, flowing above stretched and plated earth and underlying rifts, to fill the alluvium of gravel, sand and mud, to carry water in the sediment that was buried underground. The river could thus irrigate this rich farming land for pre-Pueblo Indians over one thousand years ago. Over time it irrigated 20,000 acres, and beyond Pueblo settlements, by 1880, up to 125,000 acres for newer settlers. By 1925, with growing population and demand, so depleted was the water, it could cover barely 40,000 acres. With recurring years of drought it is also running as much as 3000 feet below the earth’s crust.

IV. OF BOSQUES AND WILD BIRDS

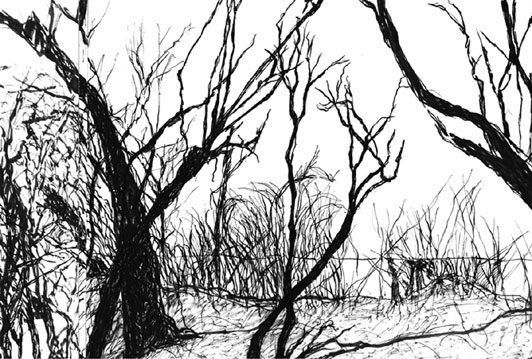

OVER 90% OF FOREST HABITATS AND NATIVE BRUSH have been cleared for agriculture or for housing.. Even along nine short miles of the Rio Grande, in the Wildlife Refuge of the Bosque del Apache, in the New Mexico desert, neo-tropical migrant birds are disappearing with their loss of habitat. The ecosystems and the trees of a pre-dam wandering river are mostly gone.

V. OF DAMS AND DIVERSIONS

TO CONTROL THE WATER, THE RIVER WAS SHAPED to an unnatural straightened flow with the coming of the dams— the Elephant Butte Dam in 1916 was the first of many. At its introduction it was the largest dam built. In the interior, going down and down into the labyrinthine passages, is a fascinating netherworld, the color of heat, power generating, elaborately wired and continuously engineered. As a hydraulic engineer recently said of the Rio Grande, ‘We turn the river on and off.’

How many million years to evolve the wild river? How many centuries to the study of hydrology? How many generations to the control of water? What shall we do when the river runs dry?

VI. OF FIRES AND FLOODS

THE PERIODIC FLOODING OF THE RIVER GERMINATED native cottonwood trees—they require it for their two- or three-week fertile window. The erratic river patterns of the Rio Grande shaped the towering stands of cottonwood bosques. Those that remain, some forty to eighty years old, form a sheltering canopy for plants, wildlife, and waterfowl. The cottonwoods and other native trees were mindlessly displaced by thirsty, invasive, salt-infesting Tamarisk (salt cedar), Russian olive, and Siberian elm to create an early twentieth-century tree war for root water. The salt cedar, fiercely territorial, has been winning. But the battles continue with restorations at the Pueblo of Santa Ana north of Albuquerque, the Bosque de Apache National Wildlife Refuge (1,500 acres restored since 1987), and the one-mile Viejo Trail.

Native populations once lived in harmony with the land, its seasons and the meandering river, even through floods and fires. It is in the intelligence of nature for periodic fires to clear inhibiting underbrush and germinate fire-awaiting seedpods. Cottonwoods benefit from fire clearing whereas, non-native species, as salt cedar, are more vulnerable. In the short term, perhaps for one or two years, fire can enhance the water table for native species and stimulate the growth potential of some native grasses, wildflowers, and shrubs.

Periodic fires, of course, dangerously threaten the myriad housing developments, the shopping centers, and populated areas that have multiplied to co-habit with and inhabit native ecosystems. Fires can devastate the former as they may benefit the latter. It is for current human development that we have fire control. It is for current human protection and water supply that we have flood control.

Four states and two countries share water rights of the Rio Grande. In 1900, 5 million people shared water. It was 42 million by 2005. What shall be the projection for 2010? Or 2020? The population grows and the water recedes. What shall we do when the river runs dry?

VII. OF FIELDS TRIPS AND WATER LESSONS

WITH THE EXCITING PROSPECT OF TWO FIELD TRIPS to the Rio Grande for this project, it was dismaying that, for so much of the journey, on highways, even on the back roads, the river was invisible. We share it by treaty (1904 and 1944) with our neighbor, Mexico, as it forms the borderline with Texas to Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Nuevo Leon. Just as we fulfill our water delivery obligations to Mexico, Mexico must provide a fixed amount of river water to us, a greater challenge in recent times of drought. At the border, between the sister cities of El Paso and Ciudad Juarez, one can see a marker, which shows the meeting point of the states of Mexico, Texas, and New Mexico. From that viewpoint, on a bridge over the river, one could watch a fisherman, wading not quite waist deep in the Mexican waters, catching crawfish with his tumbleweed net. His simple survival strategy and expression of joy at his catch, repeated untold times for generations, belie their context and history: one of hard-bargained treaties both interstate and international— the Rio Grande Compact alone took from 1925 to 1938 between Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas— with some bloody battles over land and water rights, to divide contiguous land, or to provide border control.

In the lower Rio Grande demand for water, over 90 percent is for irrigated agriculture, less than seven percent for public use, and about two percent for commercial use and livestock. An elaborate 105- mile canal system was built primarily between 1938 and 1943 to locally distribute the water.

Water rights have such high value that in New Mexico the land, its surface water, and ground water are separate entities and are sold separately. It is a cautionary tale for an uninformed buyer to purchase a house or building lot without water rights.

VIII. WATER: A HUMAN NEED OR A HUMAN RIGHT?

THERE IS A BASIC QUESTION: “IS WATER A HUMAN RIGHT OR A HUMAN NEED?” The answer affects legislation and social policy. As water is crucial to life, in common sense terms it is a human need. Is it a ‘common good’ as air, also critical to human life (but, to date, unmarketable) or a commodity like orange juice or Coke? The common sense answer is to say, “Yes, a common right.” However, water is a $300 billion international industry (with major European- based companies as Suez, RWE, and Veolia). Nevertheless, about a billion people, primarily in poor countries, are without either a regular supply of water or the infrastructure for its distribution. At United Nations forums on Human Rights—which include religion, personal liberties, and political choice—the issue of water as a human right has been contentious. After a weeklong World Water Forum of 150 countries that met in Istanbul in March 2009, their Ministerial Declaration defined water as a human need rather than a human right, with United States support. Our representative said that to define water as a right would obligate many countries beyond their means. Nevertheless, a counter declaration for water as a human right was presented by twenty countries, which included Cuba, Bangladesh, Chile, Niger, South Africa, and Spain.

Just this past July 2010 the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution recognizing access to clean water and sanitation as a human right by a recorded vote of 122 in favor, none against, but with 41 abstentions. Abstainers included the United States, Great Britain, Japan and Australia. The privatization for profit of water resources and distribution is a source of ongoing development, as well as debate, in developed and developing countries. About 880 million people in the world do not have access to clean water. An estimated 2.5 billion people do not have access to sanitation. About one and a half million children under five years old die each year of water and sanitation-related diseases. How much water does a person need? How do we insure a fair and sustainable supply?

IX. RECLAIMING THE LAND/RESTORING THE RIVER

STEPHEN MEYER, IN HIS ESSAY THE END OF THE WILD, tells us that the extinction rate for 100 million years was several species a year. Now it is more than 3,000 per year—and rising.

Phillip King, who was the engaging and informed leader of our journeys to the Rio Grande, is a Professor of Civil Engineering at NMSU and an expert on surface water issues and the hydrology of the Rio Grande, having designed some of its operating systems. I asked him for a brief answer to the question, ‘What do we do when the river runs dry?’ He said:

It is obviously a complex issue with no simple answer. In historical droughts, such as 1950-78 and 2000-present, we developed groundwater use, which gets through the drought but you do have to ‘pay it back’ in the form of groundwater recharge when the river flow returns. For longer-term shortages, such as those forecasted for our changing climate, it requires a permanent reduction in water use to bring the system back in balance. People have always had to adapt to changing water supplies, and they do so by developing new sources (tough in these parts), changes of use between agriculture and municipal/industrial use (the likely response here), migration, or war. All are painful, and we are seeing examples of all of them right now.

X. OF COLLABORATION

THIS PROJECT AND EXHIBITION COULD NOT HAVE been realized to date without the generous collaboration of Philip King, other members of the NMSU Engineering Department, the expertise of the librarians in the University’s Special Collections Library, the NMSU Art Department and especially the Art Gallery Director, Preston Thayer.

I strongly believe that it is the cross-disciplinary collaboration and research-based nature of such projects that gives them meaning and a potential for generating and encouraging social participation in the critical ecological issues of our time.

I see my role, as a visual artist, to be a translator: to present, in visual form, through images and text, both the context and pertinent details of our threatened environment. Particularly relevant are issues of water, a resource essential to species survival on earth.

Water is life.

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 2, GLOBAL IS PERSONAL

Published December 2010