Location: San Francisco Bay Area, California, USA

Detail, Fence:Wailing Wall, Carol Newborg, collages by AIC participants, rose branches, and fencing, El Camino College Art Gallery, Torrance, 1993.

Editor’s note: All photos are by the artist, unless noted.

Introduction

I am deeply engaged in community arts through both my work in California’s Arts in Corrections Program and my studio art practice. The themes of healing and repair are important to both. Recently, some younger artists asked me how I came to this dual path. At 70, I can look back and see that it has been an adventure, a flowing process of learning from each community with which I worked and creating each body of artwork. The adventure of it all began in the mid-70s and continues to evolve. I’m happy to share my experiences, and I encourage others to explore ways to find their own path. I’m still teaching in the San Quentin prison arts program, and still exploring using my art to process personal and cultural history.

Sentences- For Gary-46 years, Carol Newborg, wire and textiles, 2025.

I. Prologue: Roots of the Work

The roots of this work lie in the values I learned from my activist and suffragette New York grandmother, and my years growing up in the Washington, D.C. area in the mid-1960s to early 70s, when I was involved in local civil rights, women’s rights and anti-Vietnam War protests.

Growing up hearing about my mother’s family’s history in Poland during the Holocaust, and learning about my cousin who was a survivor of Auschwitz, also influenced me. I had heard about concentration camps and seen the images of overcrowded, multi-tiered bunks and spaces of incarceration from an early age, and that may have made the reality of working in a prison less frightening and vaguely familiar.

II. Exploring New Worlds

In 1975, I was a newcomer to California, transferring to the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley) as a junior undergraduate student. I wanted to study both art and psychology. I created an independent major, called “Art as Therapy,” with classes in studio art, art history, social work and psychology. As I continued my studies as a Master’s student, my work-study jobs also became a significant part of my education.

I first worked as an assistant at Creative Growth, which was then a new Oakland studio program for artists with disabilities, founded by Florence and Eli Katz.1 I helped facilitate access to supplies and adaptations for individuals. I saw amazing artwork, unlike any I had ever seen in museums or books. The inventive use of color, design, mark making and writing often felt completely personal and yet universal at the same time. The experience was as exciting as traveling to another country and seeing things through fresh eyes. It was the beginning of one of my mantras that becomes truer to me every year: “Art is for everyone.”

I had another work study position at a local day program for young autistic children who weren’t able to attend public schools. I helped facilitate art projects, and again, I was awed by the children’s creative and unique drawings. I always remember a ‘shoe-car’ that one boy drew; the work could be so inventive. Later, I became an art project leader at Synthesis, a nearby day treatment program for people with managed mental health problems who lived in state-funded board and care homes. Working in that setting, alongside social workers, I gained experience and confidence in setting up studio sessions and facilitating them so that participants felt welcome, comfortable and accepted.

In all three of these community arts positions, witnessing the artwork being created and shared by people I barely knew was a fundamental part of my learning about “art as therapy.” It became clear to me that people could express themselves, share their perceptions and often talk about themselves through their art, all of which can help people grow and gain connection to others and to themselves.

I think my naïveté was an asset at the time. I was working with people with life experiences that were unfamiliar to me, and we were often not from similar backgrounds in terms of education or other opportunities. Perhaps my year of independent travel earlier, when I was 20, was good preparation for adapting to the unfamiliar. Experientially, the most unusual and challenging settings in which I led art groups were two county psychiatric wards and a jail psychiatric unit.

My experiences teaching art in alternate settings not only helped fund my Master’s of Fine Art at UC Berkeley, but also broadened my world and concept of art access. I witnessed art serving a meaningful role for non-verbal, differently-abled and other people facing substantial challenges.

Small Pyramids, Carol Newborg, stoneware, Mills College, Oakland, 1980.

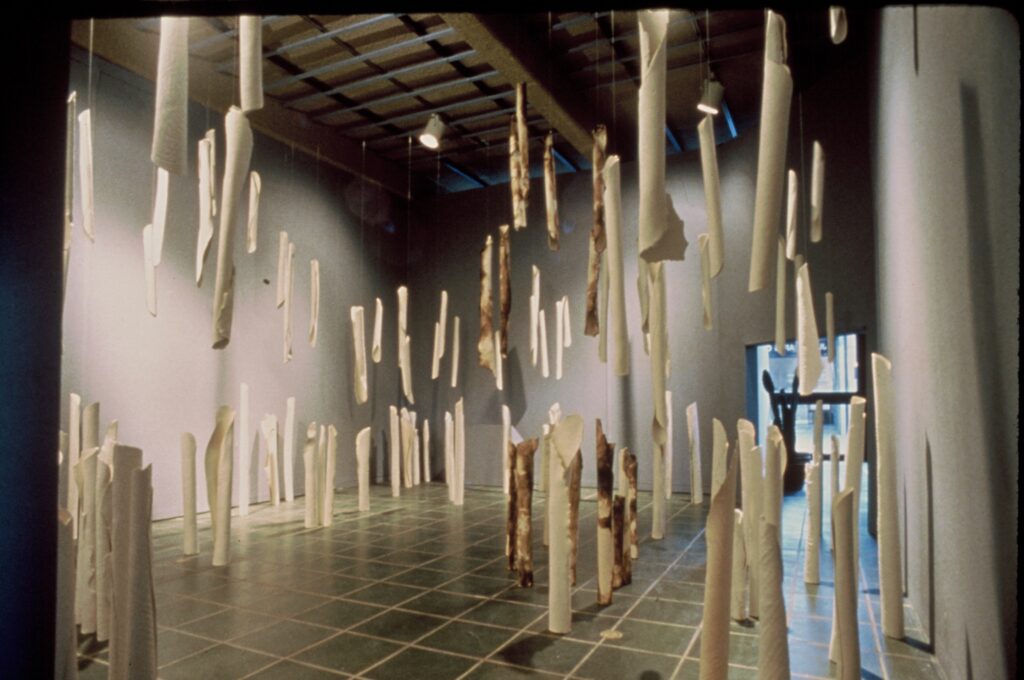

Ceramic Log Sanctuary Ruins, Carol Newborg, stoneware, Worth Ryder Gallery, UC Berkeley, 1980.

While I worked in the community settings, my art classes focused on ceramics with studio access supported by artist and professor, Peter Voulkos.2 He encouraged experimentation with form, a broad range of individual expression and making one’s own clay bodies. I created sets of large-scale, hand-built, similar forms, called “multiples,” which I used to construct my version of sanctuary ruins and other installations. I was intrigued by the logs and boxes and sets of pyramids and other multiple forms I created, and I used them differently for each site.

I practiced in the UC Berkeley studio for a total of six years. The earthy pieces I made were grounding for me and were remembrances of the sanctuaries and ruins I visited in southern Europe before moving to California. The theme of creating sanctuaries became a throughline in my studio practice and facilitation work.

III. Prison Studio as Sanctuary

First Temple Sanctuary, Carol Newborg, ceramic, Skirball Museum, Los Angeles, 1985.

Cave Sanctuary, Carol Newborg, ceramic, Barnsdall Municipal Art Gallery, Los Angeles, 1984.

After moving to Los Angeles in 1982, I continued to create sanctuaries from multiples, but worked with more delicate hand-rolled low-fire clay forms. At the same time, I learned about the new Arts in Corrections (AIC) program in California prisons, and started teaching in a women’s prison, California Rehabilitation Center (CRC).3

AIC was part of the California Department of Corrections (CDC), which supported a full-time artist/facilitator and provided funding for contract artists in multiple disciplines, a studio space and supplies. (The CDC later changed its name to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.) The CDC started funding the program in 1980 in the 12 prisons then in California. The 80s and 90s brought massive prison construction, and the CDC expanded its support to 35 AIC prison programs.

From 1984 to 1987, the California Arts Council awarded me Artists-in-Social Institutions grants, which I used to create and lead a ceramics studio for the women at CRC. We began in an abandoned storage shed, with room for a few tables, two electric wheels and an electric kiln. Two years later, we moved to a much larger space and expanded to other mediums and more teachers. I found meaning in witnessing and being among women working side by side on their clay projects, telling their stories and supporting each other in their struggles with personal growth, incarceration and separation from family and society.

Coil pot class, California Rehabilitation Center, Norco, 1987.

Years later, I realized that creating the prison studio at CRC was a form of creating a sanctuary and was thematically aligned with the sanctuaries I created from clay in my personal art practice. Prison art studios become real sanctuaries for incarcerated artists. There, people can share techniques, supplies and support, while safely exploring the self and their cultural identities through art.

Cultural identity is a vital part of helping people grow and learn to know and express themselves, all of which is part of the rehabilitative process. The isolation of prison, especially from family and community, is a huge part of its punishment, which can be deeply harmful, perpetuating trauma through generations. When someone is in prison, their children and the rest of their family are often harmed by the long separation, which can lead to harmful behaviors being repeated by the next generation. The arts can help with the process of recognizing and acknowledging past harm and trauma, which helps to facilitate rehabilitation.

I continued to work in the prison studios and developed a desire to bring artwork created by the incarcerated—people who are mostly invisible—out to the public. The first exhibit I organized was for a local public library. As AIC grew, each new prison in California built a studio and full-time program into their budget and space. Other AIC art teachers shared my desire to bring the transformative and healing power of this art to the public. As a result, I became an outreach coordinator for AIC, organizing statewide exhibits from 1987 to 1996. During that time, I organized exhibits and events for Los Angeles City Hall; Watts Towers Art Center; Self-Help Graphics & Art; University of California, Riverside; California State University, Pomona; Washington State University; Oakland Museum of California and many others. The public learned about exhibits from press releases, reviews and from other viewers. When possible, we left a notebook for comments at the gallery or site, and those comments would later be shared back in the prison studios.

Creating outside exhibits for the prison artists is an important part of my community arts work. I act as a messenger, like a bird bringing the art over the walls to the public. Then, I return with the public’s support and feedback.

Fence:Wailing Wall, Carol Newborg, collages by AIC participants, fencing, rose petals and desk, Barnsdall Municipal Art Gallery, Los Angeles, 1995.

In personal practice at the time, I developed two Wailing Wall/Fence installations in collaboration with incarcerated artists, which reflected my experience as a witness to their lives. First, I led self-portrait collage workshops in several men’s and women’s prisons, and the participants could opt to share one with the Fence project. I displayed the collages on chain-link fence structures to contrast the diverse individual expression and creativity of the incarcerated artists against the harshness of the metal fence. At both exhibits, I mounted a notebook in which members of the public could share their reactions with the artists. I copied these and brought them back to the prison art studios to share with the participating artists.

IV. Repetition with Variation

In the mid-1990s, I became a mother and moved back to the San Francisco Bay Area. For the next decade, I chose to focus on my children and community arts work outside the prisons. I taught weekly ceramics classes in a county children’s shelter and developed ceramic tile murals with students at local schools. Later, I worked as an artist-in-residence in the Oakland Children’s Hospital program, sharing art projects with children and their families in an isolation ward.

During that time, I reconnected with artists I knew from my school years at UC Berkeley, and I developed my interest in art about the environment. Several artist friends were involved with Women Eco Artists Dialog (WEAD). I joined the organization, which gave me another community of support and shared values.

Ecoart was a growing movement, and the rapid damage to the environment was of great concern to me as a new parent. My access to studio space and time were limited, which influenced the materials I used to explore these ideas in my practice. I began creating multiples of small forms with papier-mâché and mixed media, and using them in temporary wall-based installations. Creating many small pieces was a process of repetition with variations. This was inspired by spending time in nature, seeing that seashells and beach rocks are large groups of individual forms that are similar, but each one is unique.

Rainfall Installation (detail), Carol Newborg, papier-mâché, acrylic, beeswax, copper wire, Kimball Gallery, de Young Museum, San Francisco, 2009. Photo: John White

One set of multiples took the form of drops and focused on themes of water. Another set was based on seeds and pods. Like the Wailing Wall/Fence installations, the environmental work was about healing, raising awareness and creating more hope for the future.

By 2010, I reconnected with Arts in Corrections (AIC) through the William James Association.4 The state had ended AIC funding, and the William James Association was working to restore the program through grants. I was hired as the new arts program manager and was able to support the arts at San Quentin State Prison (now named San Quentin Rehabilitation Center), which had survived the cuts through advocacy and volunteer time from the program instructors.

I have been working at San Quentin steadily since then and leading their weekly open studio. I have continued organizing exhibits of art from the studio, at locations such as Alcatraz Island, San Francisco International Airport, San Francisco Public Library, San Francisco Opera, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts and many others. I love the exhibits and the outside talks and panels that I help organize. However, I am most moved by the sense of community in the San Quentin Art Studio. People help support each other and their art, share techniques and methods, and the common separation between races and cultures in prison is bridged in the studio and other AIC classes. The spirit there is an inspiration, and I am privileged to be a part of the program.

Now, my community arts work has two core components: facilitating access to art and bringing that art to the public.

V. Our Spirits Still Fly Free

Our Spirits Still Fly Free, Carol Newborg, cut paper and monofilament, Oxnard College Gallery, Oxnard, 2014.

Several San Quentin exhibits that I organized in the Bay Area focused on birds. They are a popular subject in prison art because of their beauty and because they symbolize freedom. Wings are also popular as tattoo art among prisoners. Birds are particularly relevant at San Quentin, since it sits on Richardson Bay and many birds fly into the prison yard.

The bird-themed exhibits inspired my piece, Our Spirits Still Fly Free, a flock of cut-paper suspended birds that I installed in different settings. The symbolism hit home when I exhibited at the McNish Gallery at Oxnard College. The gallery is a converted house, and I hung the birds ‘flying’ in front of a set of boarded-over windows, which reminded me of the locked and barred doors and windows of prison.

VI. Applying Some Lessons to Myself

A recent series is influenced by seeing art help people recognize and process their traumas in their own newfound voices in prison arts classes. That’s an essential part of rehabilitation and one of the reasons the arts are invaluable among programs in prisons and should always be supported.

Detail, Flying Souls, Carol Newborg, knitted cotton crochet thread, silk, Abrams Claghorn Gallery, Albany, 2023. Photo by Peter Merts

During the stay-at-home restrictions in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, I had more time than usual in my studio. I found myself reflecting on what little I knew about my mother’s cousin, who had survived Auschwitz. I remembered that he served as a tailor to the families of the Nazi guards. I began thinking about what it might have been like to make clothes for Nazi’s children while the children from our Jewish families and others were killed. I researched Jewish children’s clothing in Poland from that period and created the series Flying Souls as a memorial.

I knitted the forms of shirts and coats and dresses in large, loose stitches, and sewed each one between two layers of silk. These techniques combined to create a gauzy, hazy moiré effect, symbolizing the children’s disappearance.

Reading about and recognizing more fully the reality of my family’s experiences were deepening growth experiences for me. Knitting and then sewing the pieces to the silk were repetitive, calming processes for me.

Sentences, Carol Newborg, wire and textiles, Novato, 2024.

Most recently, I’ve embarked on Sentences, a series about the cruel, overly long sentences handed down by the California courts. I hope to raise awareness of this issue. People who are serving these excessive sentences are not the same people they were when they committed their crimes. Many have spent years, often decades, working to understand their history and their harmful behaviors, with the help of art and other therapeutic programs. They now have much to offer the community on the outside, including insights for younger people who face challenges that are similar to situations these prisoners experienced as youth. Rehabilitation is a vital goal.

In my Sentences series, I wrap many types of cloth, threads and yarns around metal grids and wire forms. My work in prisons has always included learning about many very sad and deeply disturbing stories. Wrapping, winding and interweaving the threads of Sentences is a healing process for me and symbolizes my desire to soften and humanize the bars and cages of prison. The metal grids of Sentences have wire teardrop forms for each year that a person served, based on the classic prison tattoos of a teardrop for each time served.

While one goal of the series is to bring greater awareness of excessive sentencing and the decades of incarceration experienced by so many, I am also creating something to honor the hard years of work, growth and change I have witnessed in the prison art studios.

I am lucky to have found that my love of creating art is made richer by sharing that possibility with others. Expressing myself through art helps me to connect with others, to explore worlds of form, expression and meaning; and sharing that possibility with others makes it more meaningful and my world much larger.

ENDNOTES

- “About,” Creative Growth, accessed September 4, 2025, https://creativegrowth.org/about.

- “Peter Voulkos: Echoes of the Japanese Aesthetic,” American Museum of Ceramic Art, accessed September 4, 2025, https://www.amoca.org/past-exhibitions/peter-voulkos-echoes-of-the-japanese-aesthetic/#:~:text=Voulkos%20led%20the%20charge%20in,for%20sculptural%20works%20of%20art.

- “History,” Arts in Corrections, accessed September 4, 2025, https://artsincorrections.org/history.

- “Home,” William James Association, accessed September 4, 2025, https://williamjamesassociation.org/.