Location: Vashon Island, Washington

[Editor’s Note: Teaching Art as a Subversive Activity: Cultural Democracy Meets Eco-art is the title of a WEAD sponsored ecoart panel for the October 2010 Bioneers ‘visionaries’ Conference in San Rafael, California, (www.bioneers.org). Guest moderator Beverly Naidus has invited an extraordinary group of talented, committed activist artist-educator panelists to dialogue, all drawn from her recently published book, Arts for Change: Teaching Outside the Frame. Here Beverly shares a compilation of excerpts and commentary about her book that examines the role of teaching and art making in the social transformation that is currently occurring.]

Arts for Change was written to expose a complex field, a practice, sometimes called ‘art for social change,’ and to look at how this practice is shared with students. It offers a multifaceted view of an art practice that is not as common as it could be.

It is a practice of many threads each needing encouragement and support so that wary neophytes might find a thread of their own to follow. Some versions are gentler than others, and there is no shaming involved in choosing one strategy versus another.

There are mural makers, songwriters and cartoonists, collaborative groups of puppeteers, dancers and clowns; communities revealing their stories through photo- documentaries, cookbooks, cyber art, tapestries and theater; there’s eco-art, interventionist art, and people doing site-specific, audience-participatory installations; there are poster artists, filmmakers, culture jammers, weavers and community animators.

There is no one way to transform our society into a non-oppressive, egalitarian place, but there is a multitude of ways to meet our human craving for poetry in a socially engaged way.

One of the art practices that has gained increasing momentum in the past few decades has become known as eco-art. Although I started making art about environmental issues early in my art career, I didn’t have a coherent understanding of the interrelationships between the environmental crisis and social problems until I met my husband, Bob Spivey, in 1988. At that time Bob was a student at the Institute for Social Ecology (ISE), pursuing a master’s degree in social ecology. Our pairing precipitated a wellspring of new source material for my art making, and social ecology was one of the major touchstones for my inspiration.

THE EARLY 1990’S

In the early nineties, the ISE, where later we came to teach for many summers, invited me to be a visiting artist during their summer residency program. For those of you who have never heard of the ISE, I recommend visiting their website (www.social-ecology.org). The ISE was founded over thirty years ago and offered summer programs to students until 2004. Both practical and theoretical courses were offered, including eco-technology, sustainable agriculture, social ecology in the Third World, media activism, eco-feminism, and community health. ‘From the antinuclear and ecology movements to the current against pervasive militarism and the bleak side of globalization,’ their Web site reads, ‘the ISE has inspired individuals involved in social change to work toward a humane, ecological, and liberatory society. Join the more than 3,000 students from around the globe, from Liberia to the Philippines, Italy to Iran, Norway to Uruguay, Israel to Ethiopia, the United States to Japan, and many more, who have attended the ISE in order to not only remake themselves but remake society as well.

During that first summer as an artist in residence I was able to witness some of the most inspired alternative pedagogy I had ever seen. It was my first contact with Goddard College’s student-centered learning and the ISE was at that time housed and accredited on Goddard’s campus. Although the ISE is no longer offering their summer program in Vermont, they still sponsor an occasional conference, facilitate a low residency master’s program through Prescott College, and are responsible for spawning alternative institutions such as the one my husband founded, SEEDS: Social Ecology Education and Demonstration School (www.socialecologyvashon.org) I credit the ISE with helping to solidify the greening of my art pedagogy, although not in a simplistic way, such as a purist approach to art materials.

The sense that ‘another future is possible’ was truly cultivated at the ISE summer residency program, and it gave me courage to make more hopeful work as well as engage in more disturbing projects. I began my series about healing body image during my first summer there (One Size Does Not Fit All), and my projects about environmental illness, including Out of Breath and Canary Notes, were nurtured and later exhibited there.

During the decade that I taught at ISE, I had a pool of students who were already very open and aware of environmental issues. When I left to teach art students in Southern California and elsewhere, I would often be astounded by my students’ lack of knowledge about where our food, air, and water comes from. Few of them understood how our information about these basic issues has been so manipulated and hidden that average citizens remain or choose to be ignorant. I do believe that a shift has gradually occurred in many communities. Recent documentary films about aspects of the environmental crisis and other media attention has forced some people out of their denial, as has the growing explosion of cancer, asthma, and other environmental illnesses. Still, knowing that something is wrong, going from despair into action is not easily accomplished.

TEACHING ECOART AT UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON AT TACOMA

In my current Eco-Art classes at University of Washington at Tacoma, some of my students would describe themselves as being environmentally aware. They know that something is wrong, although most don’t know the specifics. They might be avid recyclers, fastidious about buying ‘green’ products, deeply passionate about hiking in the woods, but the root causes of our world’s ecological dilemma are rarely accessible to them, and many don’t really want to dive into the mess head on. It’s not just that the situation seems overwhelming. The idea of actually analyzing how the environmental crisis is tied to broader social issues may not have occurred to them. For the most part, many students come into my classes thinking that they will be taking photographs of landscapes, or, at best, making a public art piece using natural materials. So I have my work cut out for me.

As we go over the syllabus the first day, I give the students a very broad definition of eco-art: art that addresses the ecological crisis by reclaiming, restoring, and remediating damaged environments, and/or informs audiences about the environmental problems we face and how they are intricately connected to social issues, and/or re-envisions a just, ecological future. The forms that circle this genre of art are not restricted in any way; we look at large projects in remote, rural landscapes as well as Web interventions and performance pieces. The materials and tools used in eco-art can include scavenged and recyclable items, or involve technologies that are totally unsustainable (in the ecological sense). While I rarely raise this issue on the first day of class, it is important to note that the road to purism is chock-full of potholes, and may not necessarily be a useful route to take when it comes to social change.

After the brief overview of the field, we begin to explore the terrain of the course via a tactile exercise. First I tell the students that it is important for them to know that our campus is built on a Superfund site. An occasional student is shocked to hear this, and there are many who do not know what a Superfund site is. We might look at a map of such sites, discuss what variety of chemicals might be in the soil below and around the campus buildings, how the toxins might be capped, and what might have caused the original damage to the site. After sitting with that knowledge for a few moments, I tell them that we will do a silent walking meditation through the campus for about fifteen minutes. During that time I want them to observe what they see, hear, smell, and feel on their skin. I ask them to follow their breath as we walk, and talk a little about the benefits of walking meditation, the goal of slowing down, and the intervention that we may cause via our silence and our attentiveness, on a campus where everyone is rushing past each other while talking animatedly into their cell phones.

The campus landscape, located in downtown Tacoma, is an unusual one. The buildings are mostly renovated nineteenth-century industrial buildings and warehouses. The handsome aesthetic, in a style some folks call ‘distressed chic,’ belies what is so quietly amiss underground, as does the well-groomed greenery decorating the spaces between buildings and the sophisticated public art interspersed throughout. In order to escape from the manicured landscape, our path diverges to a now abandoned railroad track behind the library where plants grow untamed (this thin strip of land is still owned by a railroad company). There the students usually stoop to pick up pebbles or twigs, or to smell a wildflower. This ‘crack in the pavement’ offers an invitation to touch that the rest of the landscape does not.

I often feel like the Pied Piper as I guide these students through the campus. When we return to the classroom, I invite them to write about this walk in their journals. I encourage them to reflect about any strange or unexpected feelings and observations that they might have. After they write, they share whatever they choose with the group.

Occasionally a student will be very aware of the temperature, the noise of a construction site nearby, or a smell in the air, some detail that the others may have missed. Sometimes several students will all tune into the same piece of visual or audio information, and they nod, smiling at their shared connection. I then talk about how during the next ten weeks I will be expecting them to take similar walks, solo, in their own neighborhoods or yards.

I require students to do a walking meditation at least once a week and to record their observations in their journals. They can go to a park, the beach, or to an urban site, or walk in their own backyard. They can take a dog, a family member, or a friend, but they need to pay attention to where they are and which of their senses are most engaged. We talk about how unfamiliar the outdoors, particularly the natural world of the woods, the desert, the mountains, and the ocean, are becoming to many of the younger generation who are spending so much of their free time looking at screens. I refer to Richard Louv’s book Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder and students each share accounts of their good and bad experiences outdoors.

WRITING TO COUNTER FEARS & INSPIRE SOCIALLY ENGAGED ART

In part, Arts for Change was written to counter the fear-based attitude that all movements for social change will inevitably result in a totalitarian state. Seeing that there are other possibilities beyond the corrupt model of the Stalinist dictatorship requires a capacity to see and critique the evidence, retrieve other more positive examples, and imagine new ways of community and society self-organizing.

Cultural work can be a significant part of developing fresh approaches to social change. So just as importantly, I wrote my book to confront another attitude that I have encountered numerous times over the years: Art that intends to provoke social change is informed by some dogmatic approach and will ‘beat people over the head’ with its point of view. I have heard this perspective so frequently, especially from artists, that I wanted to look at the roots of this opinion.

What really makes me curious about this moment in history is how so many artists say that they are not fueled by any ideological position in their work. At different points in my book I examine how privilege creates an ideology of ‘not having an ideology.’

Socially engaged art, as my peers and I have experienced it, is created in an expansive place that awakens peoples’ voices, minds and spirits in various ways. As for the clubs beating people over the heads, I am more concerned about the real ones that might hit my compañeros when they demonstrate for peace and equal rights, than ones that might emerge from a sincere heart.

WEAD-SPONSORED PANEL AT BIONEERS OCTOBER 2010

Many socially engaged artists have developed inspiring and innovative approaches to working with students over the past few decades. Social justice and ecological concerns inform these artists and their teaching in different ways. Our Bioneers panel consists of some of these distinguished, veteran practitioners. They have transformed the ways that art is traditionally taught as well as the lives of their students. Many have been influenced by the ideas of cultural democracy: a theory that suggests that the healing of our communities and our world will be enhanced by encouraging everyone—not just those who identify as artists—to access their creative gifts and offer up their stories to the community. Eco-art as it is broadly practiced, encourages sensitivity to our natural world, concern about the environmental crisis, and attention to the social justice issues that both provoke and are the result of that crisis.

Our panelists will offer up many strategies of helping our students find their voices while they make a difference in their communities and develop critical thinking about our world.

MODERATOR

Beverly Naidus, is the author of Arts for Change: Teaching Outside the Frame (New Village Press, 2009). Her book was influenced by her participation in the activist art worlds of New York City and Los Angeles, and decades of teaching at state universities, small liberal arts colleges, and alternative institutions like the Institute for Social Ecology. Her own art has explored a variety of social issues including environmental illness, racism, unemployment, body hate, nuclear war, consumerism and her dreams of an ecologically sustainable and socially just world. Her work has been exhibited internationally in museums, alternative spaces and on the streets. She is currently on the faculty of the University of Washington Tacoma where she has created an interdisciplinary curriculum focused on art for social change. www.artsforchange.org

Beverly Naidus, is the author of Arts for Change: Teaching Outside the Frame (New Village Press, 2009). Her book was influenced by her participation in the activist art worlds of New York City and Los Angeles, and decades of teaching at state universities, small liberal arts colleges, and alternative institutions like the Institute for Social Ecology. Her own art has explored a variety of social issues including environmental illness, racism, unemployment, body hate, nuclear war, consumerism and her dreams of an ecologically sustainable and socially just world. Her work has been exhibited internationally in museums, alternative spaces and on the streets. She is currently on the faculty of the University of Washington Tacoma where she has created an interdisciplinary curriculum focused on art for social change. www.artsforchange.org

PANELISTS

Magdalena Gomez is the Co-founder and Artistic Director of Teatro Vida. A distinguished Nuyorican playwright, poet performer and educator, Ms. Gómez is also a columnist for An African American Point of View. As a jazz poet, she performs with Harvard Arts Medal recipient, Fred Ho. Ms. Gomez’s archives have been selected for inclusion in the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center. This year she received a National Association of Latino Arts and Culture artists grant. Her students are currently working on a project that confronts the issue of bullying among youth. www.teatrovida.com

Stephanie Anne Johnson exhibits her large-scale slide projection installations and mixed media sculptures as a way to preserve and honor the history of Africans in America. She has worked nationally and internationally as a lighting designer in the theater for over three decades. Ms. Johnson is currently the Chair of the Visual and Public Art Department at California State University, Monterey Bay, and a Commissioner for The Civic Arts Commission in Berkeley. Her current research is on public art and the Black public sphere. Her work can be seen on the website: www.lightessencedesign.com

Richard Kamler, artist, educator, curator, and activist has been making socially and environmentally engaged art since 1976. His installations, public art projects, actions & events, audio installations, performances, drawings and sculptures have been exhibited in a range of art and non-art venues around the world. Among the many grants and awards he has received are a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, a California Arts Council Fellowship and a major grant from the George Soros Open Society Institute. He helped develop and is head of the community based art program at San Francisco University. www.richardkamler.org

Deborah Brandt has struggled for four decades to integrate her artist, activist and academic selves. From engagement in U.S. civil rights, anti-war, and women’s movements to teaching participatory photo-story production in revolutionary Nicaragua, from organizing multi-section workshops of activists in diasporic Toronto to teaching in the Faculty of Environmental Studies at York University, she has developed a practice that integrates food research and activism, popular education and community arts. Her ten books include Tangled Routes: Women, Work and Globalization on the Tomato Trail, and Wild Fire: Art as Activism (editor).

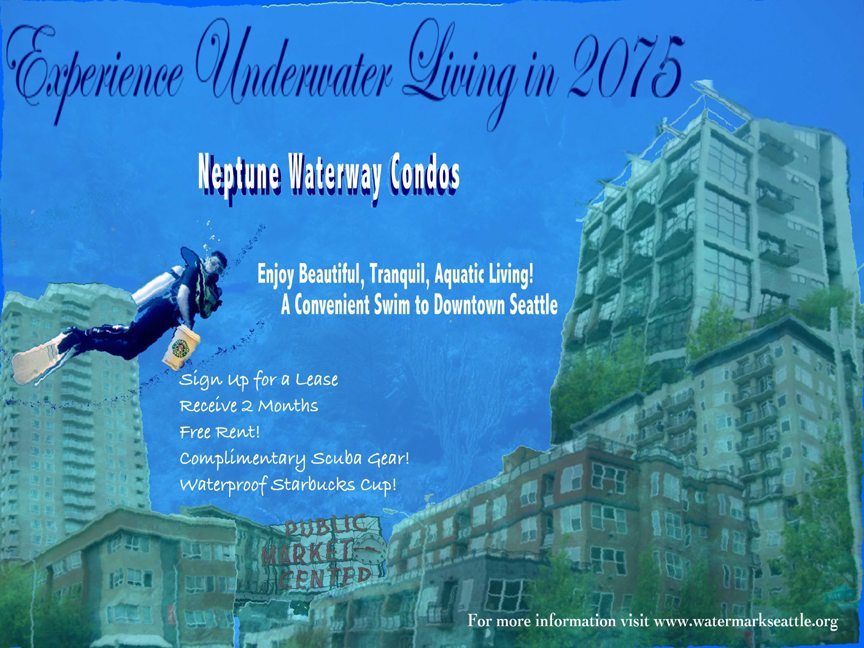

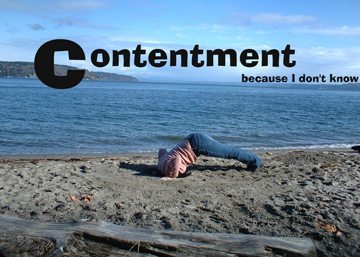

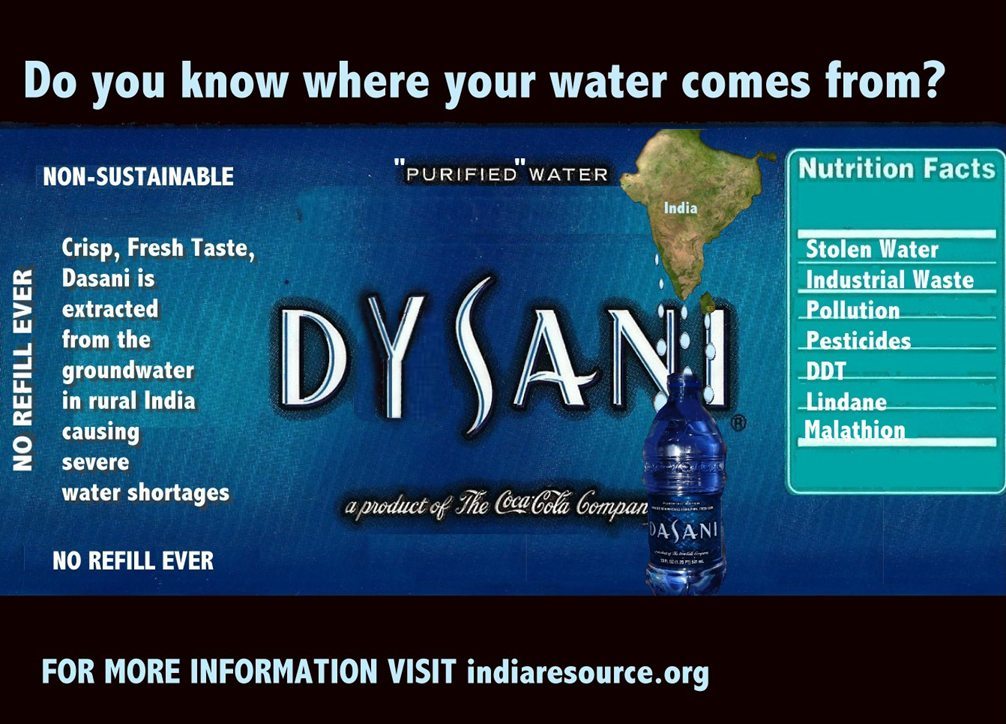

Images, from the top down.

1. Cover art by Beverly Naidus for her book, Arts For Change: Teaching Outside the Frame.

Art work by Beverly Naidus’ students, University of Washington at Tacoma:

2. “Cultural Jam”, Young; 3. “Contentment”, Cindy; 4. “Cadmium Garden”; 5. “Gasoline Bird House”; 6. “Dysani”.

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 1, CREATING CONNECTIONS

Published August 2010