Location: Perquin, El Salvador, & Cocorná , Colombia

DURING THE LAST TWO DECADES I HAVE CREATED and facilitated community-based art projects in countries affected by wars, violence and state terror. The participants of these collaborative and communal projects are civilians who suffered violations of human rights, survivors of massacres, survivors of torture and survivors of sexual violence during armed conflicts.

PERQUIN, EL SALVADOR:

SURVIVORS OF EL MOZOTE MASSACRE

I. PROJECT ORIGIN

AS PART OF THE PEACE ACCORDS SIGNED IN 1992 ending twelve years of civil war in El Salvador, the United Nations Truth Commission nominated the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (AFAT) to perform exhumations of the massacre at El Mozote, Morazán. According to Rufina Amaya Márquez, the sole survivor of the massacre, the Salvadoran army murdered more than 1,000 civilians on December 11, 1981.

My job was to accompany AFAT to create the archeological maps that record the location and finding of human remains, associated objects, and the presence of ballistic evidence.

After three months of investigation, the allegation of mass murder against civilian population was confirmed. Inside a small building known as “The Convent, Site #1” (one of a total of nine archeological sites marked within the hamlet) AFAT was able to identify the presence of 143 individual remains. One hundred thirty six were children under the age of twelve, with an average age of six years. Many were infants.

When my assignment as consultant/artist at the investigation of the massacre at El Mozote concluded, I went to Perquin, a village of 5,000 inhabitants located four km north from where El Mozote once existed.

Perquin is in the most northeastern area of El Salvador. Like most communities in Morazán, Perquin had been hugely impacted by the war. The majority of existing houses were uninhabitable. They had been bombarded and severely shot through.

I looked around amazed at the effects of destruction. I was surrounded with evidence of pain contained on the wounded walls.

They were Walls of Pain.

“How,” I wondered, “could they ever turn into Walls of Hope?”

II. THE PERQUIN SCHOOL OF ART & OPEN STUDIO

THE SCHOOL OF ART AND OPEN STUDIO OF PERQUIN was created in response to the question: “How could bringing art into the life of a community contribute to the healing and social stability of that community ?

Searching for answers, I examined the intersection of politics, ethics and aesthetics; searched for memories, and tried to incorporate genocide as a tangible reality of the country’s recent past and present life.

III. THE PERQUIN MODEL– WALLS OF HOPE

THE SCHOOL OF ART AND OPEN STUDIO of Perquin/Walls of Hope is an international art and human rights project of education, diplomacy building and community development. Four Salvadoran artists/teachers direct the school: America Argentina Vaquerano, Claudia Verenice Flores Escolero, Rosa del Carmen Argueta, and Amilcar Varela. They work in collaboration with me– Claudia Bernardi, artist and educator from Argentina.

Walls of Hope bridges art and community-based projects beyond El Salvador. The Perquin Model is a blue print of art projects that can be duplicated in other communities. It has been introduced successfully in many regions of El Salvador (Arambala, Segundo Montes, Cacaopera, Torola); as well as in Canada (Toronto); in Guatemala (Huhuetenango, Rabinal, Cobán, Panzos and Guatemala City); and most recently, in Colombia (Cocorná, Antioquia).

The Perquin Model:

- A community based project that engages children, youth and adults in the creation of art that serves as a component of community building.

- A project created with the understanding that there has been trauma, violence and prejudice inflicted on the participants through political duress, state terror, wars and armed conflicts.

- The participants decide on the theme and narration of each piece with the intention to create a visual testimony that represents their recent history.

- A collaborative art project that expands from creativity towards diplomacy, judicial concerns, and the demand for respect for social and human rights

COCORNA, COLOMBIA, 2009:

ART WITH THE ASSOCIATION OF VICTIMS OF VIOLENCE

A nosotros nos han hecho tanto dano/

They have done so much harm to us.

Doña Carlina

AVVIC–ASOCIACION DE VICTIMAS DE LA VIOLENCIA (Association of Victims of Violence) of Cocorná brought together more than 50 locals–youth, children and adults. They are all survivors of violence, imposed poverty, and displacement. We would meet them and learn from their strong desire to rebuild their communities and witness their remarkable organizing skills.

This new collaborative and community based art project with AVVIC was designed to record the Colombian civilian voices who, for more than four decades, have suffered the effect of an armed conflict. The Colombian army, the guerrilla forces FARC and ELN, the paramilitary and the drug traffickers have tormented and terrorized the civilian population in the area.

I. Our work in Cocorná

WE PAINTED TWO COMMUNITY-BASED and collaborative murals:

- One located at the Casa de la Cultura (Cultural Communal House), created mostly with adults and the elderly, although some children and youth joined, too.

- Another created at the Educational Institute of Cocorná by youth ages 11 to 17. All the participating youth had been directly affected by violence. Children’s parents were murdered– victims of land mines or war violence such as abductions and sexual violence.

Claudia Verenice Flores Escolero, Rosa del Carmen Argueta, and I worked with community survivors of displacement, massacres and unmanned land mines (minas anti-persona). The participants of all ages were committed to sharing their personal and communal stories as part of their journey towards demanding justice.

II. Mural: ‘Solo la Mitad de MÃ’/ ‘Only Half of Myself’, painted at Casa de la Cultura/Cultural House.

CHILDREN, YOUTH, ADULTS, AND THE ELDERLY, all survivors of violence, created this first mural between August 1-7, 2009. As always, creation of the mural was preceded by workshops in which victims shared their personal histories. This helped establish a common base among participants, allowing them to discover pertinent subject matter that was accepted by everyone in the process. This step is fundamental in designing the main ideas that would become the theme of the mural.

Claudia Verenice Flores Escolero, Rosa del Carmen Argueta, and I, the artists/teachers of the School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin, grew accustomed to witnessing narrations of violence while creating murals in El Salvador and in Guatemala. However, we were unprepared to learn about the constant violence inflicted on the civilian population in the region of Antioquia for over four decades. Disappearances, killings, murders, massacres and displacement happen constantly. They happen today. Unlike El Salvador and Guatemala where fragile yet determined Peace Accords were signed in the 90’s, the Colombian military, guerilla movements (FARC and ELN), paramilitary and drug traffickers are still out of control, creating constant tension and real danger to civilians.

The drawings that the participants created are visual indictments. They talked about what they had lost, what they had seen, and what they do not wish to see happen again. This was the first time that children, youth and adults worked in constant collaboration. They showed a remarkable inter-generational understanding and had a comfortable way of working together. The children had a voice and place equal to the youth and adults.

We applied large fields of abstract colors on the wall to diminish any possible shyness about working on such a large surface. It should be remarked that no shyness was ever reported or seen in this group! Everyone was ready and eager to paint at all times.

We marked the most important directions of composition. The mural participants started transporting their ideas and selected drawings to the wall. The mural started taking shape within the architectural columns framing the Culture House wall.

Luz Dary, a 36-year old mother of five, grandmother of one, proposed to paint herself in the mural as “half of herself.” She shared with the group that her father disappeared when she was a baby. She never knew him nor met any of her father’s relatives. She grew up with deep longing for him causing uncertainty about who she really was. Added to this, she had lost homes, family members and most of her meager possessions.

‘The war robbed me of half of myself,’ said Luz Dary. In the very middle of the mural there is a woman who has only half of herself. The other half is wrapped in a deep dark green shadow. Dary painted the half woman extending her hand to a Virgin Mary, who is less Saint and more Woman because the Virgin Mary had also lost a son by violence. This Virgin Mary has a hand amputated as result of an unmanned land mine.

Inside the painted shape created by these two women, the viewer sees this scene:

A mother bird comes to feed her baby birds in a nest. The mother bird gets shot, falls to the ground in agony and is taken by the Red Cross in an ambulance. The baby birds are left alone and unprotected. A rabbit is taken to jail in another segment of the same central area of the mural.

These vignettes were painted by Maria Doris, mother of Carlos (17), Christian (12), Maria Camila (10) and Laura Valentina (8). When Laura Valentina was 8 months old, Maria Doris’s husband, Arturo, went to a nearby village to buy few things he needed for farming. He never returned.

A few months ago, the Judicial Court of Medellin, contacted Maria Doris to let her know that a mass grave had been found accidentally and that the remains of one of the buried victims appeared to be that of her “disappeared’ husband. His ID card was found within the clothing. DNA testing is pending to further prove that the skeleton found, among ten others, is that of Arturo’s.

Andrea and Eladio who are in their late 60’s had 21 children in their loving 50 year marriage. Only five daughters are still alive today and they are displaced living far away from their parents. All other sons and daughters died young, were killed, abducted or disappeared. None of them ever had any contact with the guerrilla or the army. Poor farmers Andrea and Eladio not only lost their sons and daughters, they also lost their land. When they were displaced they were forced to live on the coast for few years. When they returned to Antioquia nothing of theirs was still standing. Nothing had survived.

In the mural’s conflict area there are people rendered with missing limbs. This is a reminder of the imminent threat posed by land mines placed in rural areas. Unlike other war torn countries where I worked as an artist or as a human rights advocate, Colombia has had few national or international efforts made to detonate or neutralize land mines. Thus, the danger is constant and recurrent. Community members record reports of mines exploding, and the injuries produced in order to warn the people of dangerous areas around Cocorná.

The project artists shared the memory of horses coming to town with corpses of men, women and children. Most victims showed signs of torture and abuse. They lamented that they did not know who was responsible for the deaths since the army, the guerrilla, the paramilitary or the drug-traffickers could have originated this level of violence. Survivors remembered that even the horses would collapse from grief after they had delivered the dead to their families

Most of the mural participants had been displaced–told to leave everything they ever had, their homes, animals and crops within an hour. If they did not obey, they and their families could be executed.

On the left side of the mural, a campesino carries the weight of his heart on his

back.

While this image was being painted the participants shared personal stories of displacement. In a few cases, displaced people returned to their homes after many months to find them robbed, infrequently still standing, the cattle taken, the crops burnt and the land poisoned, they believe, with an unknown strong chemical.

Don Fabio told me he was surprised that the violent forces wanted to kill even the earth. As campesinos they had learned how the earth talks, and how ‘she,’ la Tierra, can sing and produce enough for everyone to be fed. Fabio asked, “Why would anyone want to kill the land?”

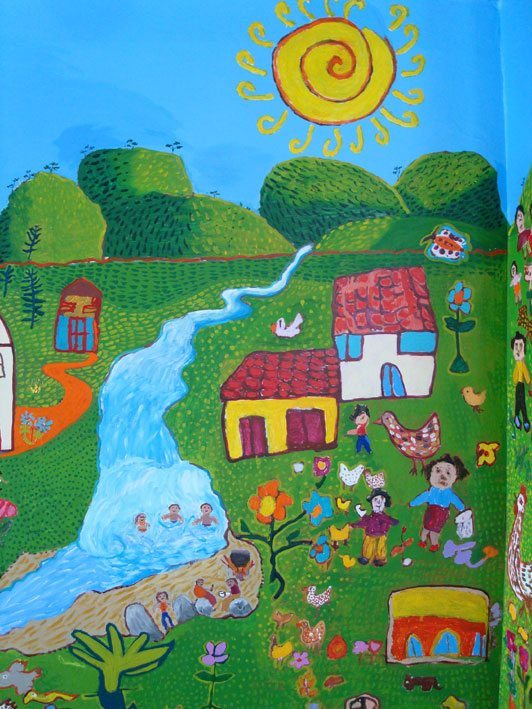

In this mural, the moon travels to the sun becoming one full day, and life is splendorous beneath the open sky. There is a serpentine river born in the mountains that becomes a waterfall where people gather happily, bathing, while others prepare food by a camp fire. Cristina painted this scene saying that it is a common custom for families and friends to meet by the river and eat sancocho, a thick soup of meat, yucca and potatoes.

All these stories appear in the mural in bright. beautiful colors that render the magnificent landscape of the area. They painted mountains and a local church as a reminder that they had not forgotten God, although sometimes they fear that God may have forgotten them.

Father Jorge Julio, MejÃa MejÃa came to Cocorná on August 12, 2009. It was wonderful to finally meet him, and with the participants of the mural, share the subject matter and how it came about. The artists eagerly showed Jorge where each had painted.

Doña Carlina told us: ‘They have done so much harm to us. You have brought us a lot of happiness with the painting and by listening to our stories.”

III. Mural: Las Dos Caras de Nuestra Realidad (The Two Faces of Our Reality) at the Educational Institute of Cocorná

THE FIRST MEETING WITH THE PARTICIPATING youth was focused, intense and revealing.

All had been directly impacted by violence. Their mothers or fathers, or in some cases both, had been killed in recent years. The youth had suffered forced relocation.

After drawings and discussions, the mural’s subject was selected. This group of 35 young men and women, ages 11 to 17, would soon make a visual statement of their personal and communal histories on a wall in one of the school’s main areas.

The mural features two portraits facing one another, with the middle area anchored by an ancient one-eyed indigenous wise Shaman. The Shaman is rooted in the earth that contains the knowledge of ancestors that the youth fear their generation has lost. The cyclopean character looks within for wisdom. He looks to the past and to possible ways to achieve Peace and to distribute a sense of Justice.

The right side of the mural depicts a profile of a fox-like animal crying while it sees the destruction of life– the death of the environment, the pollution of waters with garbage, dead animals and weapons that travel a dirty river. A land mine explodes at the river bank while an over-sized marijuana leaf represents the risks and fears that the youth face from drug trafficking and drug wars in Colombia. The mural shows a young man, addicted to drugs, unable to come out of the loop of addiction, crime and danger.

While creating this mural the participating youth spent a lot of time talking to us and among themselves about the upcoming proposition of a new law that would de-penalize the selling and consuming of small amounts of marijuana and cocaine as a way to weaken the drug trafficking (narcotráfico) economy.

The youth evaluated the ramifications of this possible new legislation, trying to imagine the risks involved. They were concerned, scared and confused about the few options they seem to have. They expressed a sense of hopelessness while addressing that the only strong economy in Colombia is the one generated in drug trafficking. If they do not consume drugs, they still fear that they may be forced to sell them.

On the left side of the mural, a young woman’s profile frames a sunny and open landscape where there is farming. There are mountains and an unpolluted river runs from left to right, bringing life and prosperity. People of all ages and backgrounds enjoy a possible state in which the lack of conflict is a not a dream but a reality.

This mural was painted August 8-13, 2009. On Friday, August 14, we held a special workshop on color and techniques.

The youth involved in the last mural and many adults from the first mural were so moved and happy with the outcome of their work that they proposed they would continue painting murals after our departure.

We left Cocorná and Colombia on August 15 with the promise to return and with the renewed conviction that art makes a significant difference in the life of communities that have suffered violence, state terror and wars.

We witnessed firsthand the beneficial impact of these Walls of Hope. Creative communal activity was restorative not only for the victims of human rights’ violations, but also for the public who, in time, will begin to comprehend these victims’ histories through their personal narrations in the language of visual arts.

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 2, GLOBAL IS PERSONAL

Published December 2010