In This Issue

-

Jacki Apple ● Leslie Labowitz: Sprout Actions

-

Evgenia Emets ● Eternal Forest

-

Robyn Woolston ● Notes From The Precipice

-

Edie Dillon ● Art & Healing On

Sacred Land -

Zea Morvitz ● Mary Eubank

Artist, Community Nonprofit Gallerist -

Lauren Elder ● Disappearing Hardwoods

-

Mierle Laderman Ukeles ● Touch Sanitation

-

Mary Jo Aagerstoun ● ​​Eco Art and Black Americans’ Relationships to the Land

-

Teresa Camozzi ● Climate Change Dressed In A Fire Gown

-

Ria Vanden Eynde ● Feminist Activist Painting

-

Susan Leibovitz Steinman ● Taking Action

TOUCH SANITATION

A NYC citywide performance

EDITOR’S INTRODUCTION

Mierle Laderman Ukeles is a pioneering feminist ecoartist. First a successful painter, she switched to environmental performance art in the 1970’s after the birth of her first child.

She intuited that upon becoming a mother she simultaneously became undervalued and a private maintenance worker, cleaning up diapers and other disposable paraphernalia associated with raising children. With purpose and chutzpah, she introduced herself to the higher management of the NYC Sanitation Department and in 1978 became the unsalaried, self-appointed official artist in residence there. The rest is history. But first comes the beginning. In her own words, here is Mierle’s “origin story.” By listening to others, valuing their labor and viewpoints, seeking to “repair the earthly world” (In Hebrew called “ tikkun olam”) she contributed to the cultural drift of her time toward social and ecological justice. She remains a stellar role model for artists seeking to change their practice into one that supports environmental health.

Suzi Gablik wrote: “Touch Sanitation was Ukele’s first attempt to communicate as an artist with the workers, to overcome barriers and open the way to understanding–to bring awareness and caring into her actions by listening….For many artists now, this means letting previously excluded groups speak directly of their own experience.” (Mapping the Terrain, New Genre Public Art, pp 82-83, Suzanne Lacy editor, Bay Press, 1995)

TOUCH SANITATION

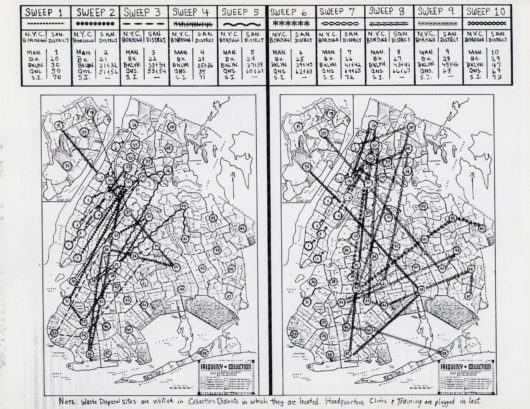

Sweep 7, Staten Island 2 photo: Deborah Freedman © Mierle Laderman Ukeles Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

IT WAS A VERY strange time in the mid 1970’s. New York City, in the thick of a terrible fiscal crisis, seemed to be coming apart. The Daily News headline echoed President Ford’s blaring out: “FORD TO CITY: DROP DEAD.”

Sweep 3, Manhattan 3 photo: Robin Holland © Mierle Laderman Ukeles Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

After 1.5 years of research listening to and learning from NYC sanitation workers – and finding out where my garbage goes after it leaves my apartment in the Bronx, I begin the performance ritual. Sanitation Commissioner Norman Steisel had accepted this, my first in a series of proposals for me with DSNY from 1977. He sent a memo to his Executive Committee indicating his strong support and directed them to help me across the board and give me access to all Sanitation facilities. They agreed to provide a city car with a driver every day of the performance. I had arrived in the major leagues of the world of maintenance. I was in heaven.

Artist’s Letter of Invitation Sent to Every Sanitation Worker with Performance Itinerary for 10 Sweeps in All 59 Districts in New York City, 1979 printed brochure, 4 pages © Mierle Laderman Ukeles Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

I will make 10 circling “Sweeps” around NYC. I refuse to experience through sampling – the abstract way a social scientist comes to know something. Only if I immerse myself in Sanitation’s wholeness can this art become real. I will float through the entire system’s everyday reality: to face all the workers, to travel to every Sanitation facility in NYC: garages, “section” offices, lunch and locker rooms, mechanical sweeper garages, snow operations, repair shops, borough commands, incinerators (at that time), landfills, Headquarters. The whole system.

I desire to make art—utterly public art injected into the city’s bloodstream—everywhere.

I design this itinerary with chiefs from Operations; we piggyback it on the DSNY’s system of 59 sanitation districts in all five boroughs: Manhattan, Bronx, Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island. Several chiefs know all the streets in the city. Great urban experts, they know where everyone is – scary — they have to in order to find and pick up everyone’s garbage, all the litter, all the snow.

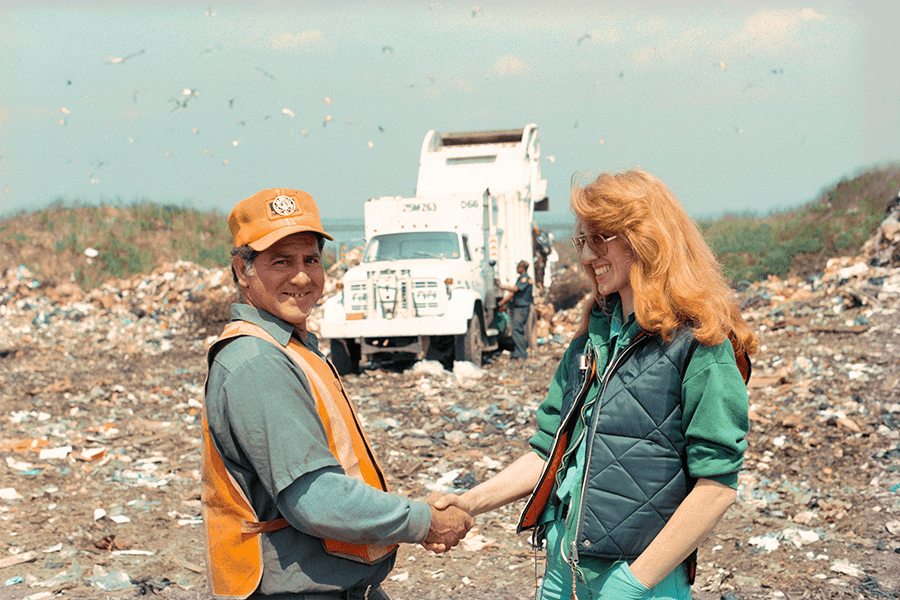

May 15, 1980 Sweep 10, Queens District 14 photo: Vincent Russo © Mierle Laderman Ukeles Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

I will face each of 8,500 sanitation workers personally at work, shake hands with each person, and say, “Thank you for keeping NYC alive.”

Before I begin, a 4-page Touch Sanitation Brochure that I wrote and designed (10,000 copies funded and published by Avon) is distributed to every sanitation worker in every DSNY facility in NYC.

It includes my letter to each sanman (all men then), personally inviting each person to participate in the performance if he wishes; the planned Itinerary for all 10 “Sweeps” to all 59 districts, along with short letters of support from the commissioner and the sanitation workers’ and officers’ unions.

Every day I go out, a telex is sent from Headquarters in Lower Manhattan to every sanitation location citywide with instructions to post it on the bulletin board and to read it at rollcall. It says which section and district I will be in, so people all over town can track my journey for as long as it takes. I write the texts for the telex and submit it to the telex office at Headquarters. Getting on the telex system embeds the art in the system’s daily work tactics — like central command moving an army around – how many trucks go here, how many sweepers are transferred there, day by day. And also now — the live art.

March 24, 1980 Sweep 7, Staten Island 2 photo: Deborah Freedman © Mierle Laderman Ukeles Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

I begin on July 24, 1979. I was utterly determined and certain of the logic of this artwork, and yet so scared! I spend at least an 8-hour, often a 16-hour shift, modelling my performance art time on the 8-hour work shift, making increasingly fiery speeches at roll call. I hear bad things from many sanmen– how they are treated, and how they are not seen by the public even though they work in public. With 65 % of their equipment down and no maintenance budget because of the fiscal crisis, the more fiery my speeches became: “I’m not here to watch you, to study you, to judge you, I am here to be with you, all the shifts. To walk out the whole city with you. To thank you.” Then I walk out some of the thousands of curb miles with the sanmen.

I have almost no budget except in-kind from DSNY. I often carry a little Sony recorder over my shoulder. I ask permission to turn it on. I record more than 100 hours of tapes, mostly while we are walking behind the truck, talking.

Sometimes a photographer joins us. I was lucky enough to have seven different photographers accompany me during the performance. Because I got a $3,000 artist grant from the NEA (alas, no longer available), I was able to hire a two-person video crew who shot seven full days spread throughout the performance. The National Enquirer wrote about this artwork, starting with the headline: “Artist Wastes Thousands of Your Tax Dollars Shaking Hands With Garbagemen!” However, a substantial amount of other media developed about the performance, some of it serious, much of it positive, or at least curious about how weird this was, the rest snarky. The fact that a heavy duty, big-muscle — “the Strongest” — City agency as they called themselves, was OK participating in this, was shocking. Sanman couldn’t believe it when I insisted that a reporter listen to the workers. It was these workers, their daily efforts, that were the subject of this art, and how utterly dependent we are on them. To get the story, the reporter or TV crew had to spend the whole day with us, not zip in and out. Then the sanmen read about what they themselves had said and done in the same newspapers that previously only criticized them.

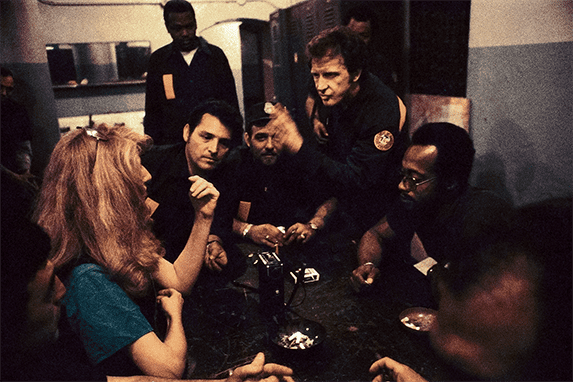

We eat together, sometimes on the curb because many restaurants won’t serve sanmen inside, often in miserable section stations. Much of the time, I listen.

The performance continues to all the city’s sites of degraded land: seven active landfills still operating during the time of the performance with very low operating budgets and little public interest. This was before broad federal environmental regulations.

Out on the streets, and in and out of the transfer stations early and late, and the deep pits and furnaces of the incinerators, it is risky and possibly dangerous. As Robert Smithson would call it, this expedition / exploration is a “taboo situation.” It is also thrilling.

It was the day after Thanksgiving. We’re in a neighborhood in the Bronx where there are very few metal garbage cans (it was before plastic bags). Garbage had been put out in paper bags. Pouring rain. The soaked bags gave way as the sanmen picked them up. Turkey bones and rice, and more rice and bones, were spilling all over the sidewalk. Wet streams were pouring down the back of my dumb rain gear. Another bag collapsed and another bag opening, smearing everything all over. Endless. Impossible. I started to cry. “What are you crying about?” they asked. They laughed. “We’ve been doing this for years!!” I laughed too – they were so amazing — and kept crying.

Sweep 7, Staten Island 2 photo: Deborah Freedman © Mierle Laderman Ukeles Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

Every day, I face strangers. Often, they are shouting. This is scary. There is fury and fear in the garages and locker rooms. We are in the thick of the terrible NYC fiscal crisis. The City’s workforce – with the smell of bankruptcy in the air — is being reduced by 60,000 jobs! Sanmen, in exchange for picking up your garbage, had bought into the American dream of long-term security via deep mortgage obligations. People are afraid that they will lose their jobs. And their homes. Then what? There is also a big move, especially among university academics and the Daily News, to sell the Sanitation Department to the private carter industry.

I’m coming from 10 years of making art about our culture of “invisibilizing” and disrespecting maintenance workers. I am fueled by my own personal fury – as a mother maintenance worker – at how maintenance workers – both woman as The Destined- though-uninvited-maintainer of the interior personal home+children, and sanitation workers – keepers of the exterior city-as-home, are not seen, not heard, no language, not honored, dumped outside the culture. That’s it! We are joined in anger.

I am trying to create a grand coalition; a service workers’ coalition: those inside with those outside. That’s most of the people in the world. I’m talking about a world revolution. Time to rupture this whole twinned ancient ridiculous bubble!

Sweep 10, Manhattan 11 photo: Deborah Freedman © Mierle Laderman Ukeles Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

I meet a sanitation worker. I see deep in his eyes what I have come to call “The Gates of Acceptance.” I see him looking at me, and then I see his gates opening up. He has decided what the hell, I will trust her. I will tell her what it does to me inside when people think we are part of the garbage.

Despite the shouting, the tension, the stomach-turning waves of fear, the unburdening telling of shame, yet buoyed by their sheer duration-strength, I feel at home. Revolutions aren’t so quiet. And the sanman, as he tells me things, fully intends for me to pass this along to the outside as an artwork.

This gets complicated. It’s 6 a.m. roll call again. I’m in Staten Island. “Do you know why everyone hates us?” many ask me. “Why?” “They think we’re their mother! They think we’re their maid.” O! As if it were obvious. If they were women, would it be ok to hate them? Would it? Who were they telling this to? Surely, this feminist artwork, aiming to build the ultimate inside-outside coalition, needs more work.

Along the way, another part of the performance grew. I called it “Follow In Your Footsteps,” as in imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. I don’t pick up the garbage. I copy their moves on the street as they pick up the garbage, to discover their secrets of balance, so the heavy bag doesn’t wreck your back. I copy their big gestures sweeping the streets. I also do this to place myself physically, without explanation, in their same position of public exposure, with the audience watching, often criticizing, but often hidden behind the curtain, behind the venetian blind. I need to learn the work physically through the body, not with words. I also like it because it often cracks them up. A dance develops at any moment. We’re dancing in the street. This is the beginning of what turned into seven different “Work Ballets” in different cities and countries that I have co-created with workers all over the world from 1983 through 2012.

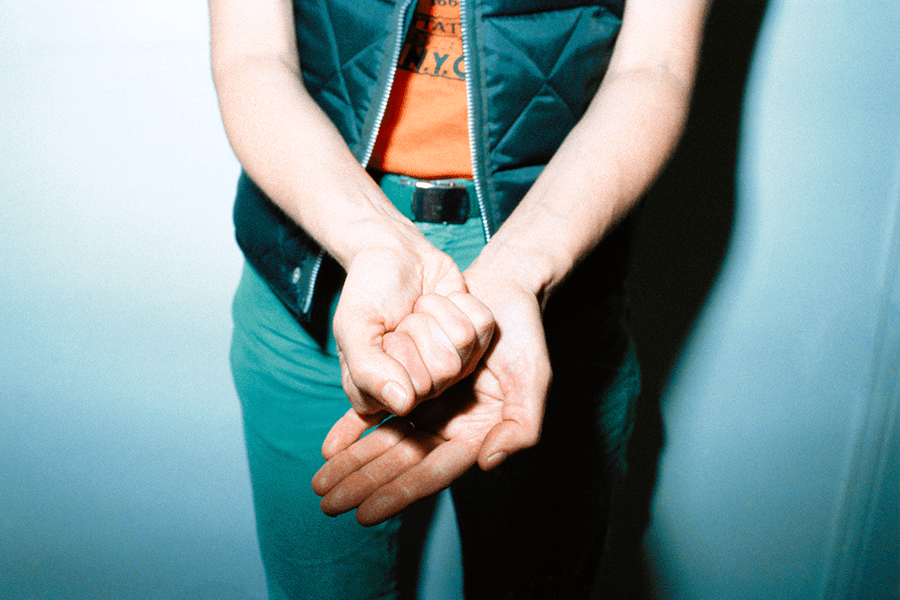

Sweep 10, Manhattan 11 photo: Deborah Freedman © Mierle Laderman Ukeles Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

Leaving at 5 a.m., doing the night shift, is hard on my own family. My 7-year-old son comes home from school, catching hell from his friends. He asks me: “Are there many garbage artists like you?” I asked him the other day – he’s almost 49 now – how he responded to the kid who said: “Your mother’s a garbage artist.” He told me: “I didn’t say anything; I slugged him.”

Every day, I send out a telex saying where I will be to TOUCH SANITATION, so people all over town can know how far I’ve come. It’s 3 a.m., ten months after I started. I arrive at a dank little godforsaken section office in the Bronx. As I walk in the dark to the rusty closed steel door entrance with a tiny, gridded window, I ask myself – I’m so tired – “What are you doing this for?” Then I go in, and the foreman shows me the telex: “I’ve been tracking you all year.” I had said I’m going to do this, and they have been mapping me doing it all over the city.

I don’t run away. I keep coming back, just like they do. That’s what binds us. That is our power.

November 20, 1979 Sweep 4, end of day in Artist’s office, DSNY photo: Tobi Kahn © Mierle Laderman Ukeles Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

I thought the performance itself would take three months. It ends up taking eleven months. I conclude the performance on June 26, 1980, in the same district in Lower Manhattan where I began.

A human being always has the freedom to say “No”.

But a human being also has the freedom to say “Yes”.

Open your hand!

November 20, 1979 Sweep 4, end of day in Artist’s office, DSNY photo: Tobi Kahn © Mierle Laderman Ukeles Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

The art is to create a dis-mapping of the formal city and to create a re-mapping of the entire living city, from its breathing underbelly up. The all-ness of it….only via the ineffable individuality of each worker, with everyone, with whom we are utterly dependent, now inside the picture.

This is the beginning of democratic public culture.

– Mierle Laderman Ukeles , September 2021

Landfill (location and date unknown) photo: Deborah Freedman © Mierle Laderman Ukeles Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

PHOTO CREDITS

Mierle Laderman Ukeles Touch Sanitation Performance, 1979-80 July 24, 1979-June 26, 1980. Citywide performance with 8,500 Sanitation workers across all fifty-nine New York City Sanitation districts. © Mierle Laderman Ukeles Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 12, TAKING ACTION

Published October 2021