Open to WEAD listing artists and members, these portfolios showcase artists whose work reflects diverse approaches to environmental and social justice art.

ARTISTS

Mary Apikos

Christina Bertea

Katherine Boland

Emily Van Engel

Grace Grothaus

Deborah Kennedy

Isabella La Rocca Gonzalez

Fern Shaffer

MARY APIKOS

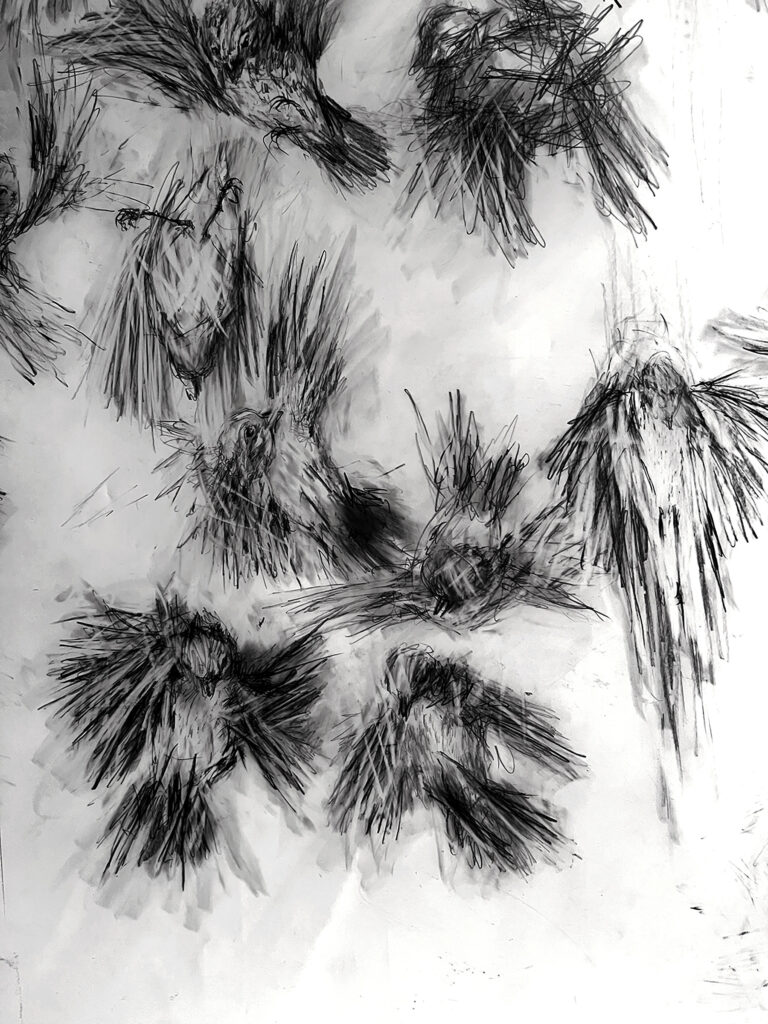

4 x5 feet Graphite and eraser on translucent film, 2021.

Collection of the artist.

4 x5 feet Graphite and eraser on translucent film, 2021.

Collection of the artist.

In Crashing Birds Murmuration #1, I flip the magic of a murmuration into an image that speaks to what happens when innocence is changed by trauma. The piece is simultaneously allegorical and also prescient as bird strikes are exponentially increasing at airports and in cities with skyscrapers. This moment of change – the strike – becomes the moment of impact. I wanted to capture that truth and how it’s different for each bird — some are stunned, some hurt, and some anticipate the collision and right themselves just in time. Some birds fly in ignorance of the window; some never fly in the same direction as others. I don’t draw the glass pane; the viewer can imagine its presence or not. I wanted to explore the physicality of this kind of looking at the world, not just its fatal consequences.

CHRISTINA BERTEA

Savaged: glass cone, rubber bird, feathers, vacuum hose, fabric. 2023

In the 1960’s/70’s, scientists at the National Research Council of Canada proved that bird feathers are receptors for RF radiation. Birds collapsed within seconds when exposed to strong RF fields, but not if they were first de-feathered. Scientists observed: “Even if only their tail feathers were exposed they would scream, defecate, and try to escape”.

This piece visualizes feathers being vacuum-plucked from a live bird–it is intended to disturb!

Because: Volumes of research exist proving biological effects from ElectroMagnetic Frequencies but the FCC considers only thermal effects, resulting in inadequte safety limits. Corporations rolling out 5G (except where prevented by public outcry) are already advertising 10G. They will not stop ($).

But —what are we doing to life on earth

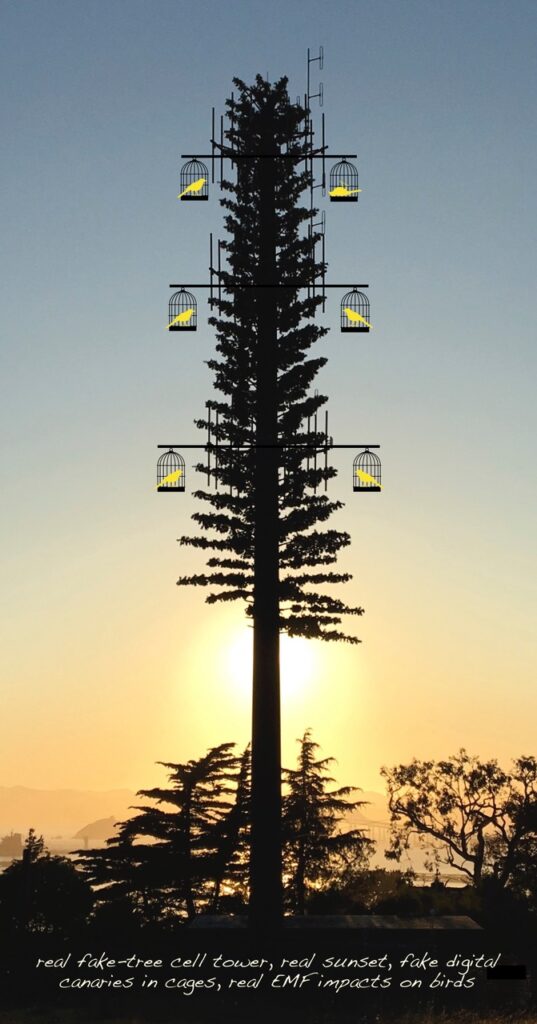

Altered photo of a Point Richmond, CA fake-tree cell tower, with handwritten notes, 2023

Early-warning-system canaries might not be the only sacrifice to our God of Tech. Already many humans are experiencing electromagnetic hypersensitivity, making life unbearable in a world soaked in wifi, radar, radio frequencies—and 5G is slated to blast every single corner of the planet. There will literally be no place to hide. What if plants and animals cannot abide?

Could our precious cell phones and wireless technology be contributing to the loss, since 1970, of 30% of North American birds? In Europe, many thousands of nesting seabirds were observed to drop dead (like “sitting ducks”) when new cell towers aimed at their wildlife “refuge” were activated. The Precautionary Principle would advise us to leave some areas of earth free of EMF pollution—every properly designed experiment needs a control!

KATHERINE BOLAND

Wood stain, liming solution, acrylic, pokerwork, scorching on inscribed timber panels. 20’x20′

I made this work in the wake of the 2019/20 Australian bushfires which decimated my region on the eastern seaboard of the country and in which an estimated 3 billion native animals perished. Abstracted flora, created with fire itself, float above a charred landscape, a tribute to the resilience of the Australian bushland after fire.

The Australian Prime Minister gifted a painting from my Fire Flowers Series to President Biden on his recent visit to The White House. I only hope that the Prime Minister used the painting as an opportunity to speak to the US President about tackling the climate crisis.

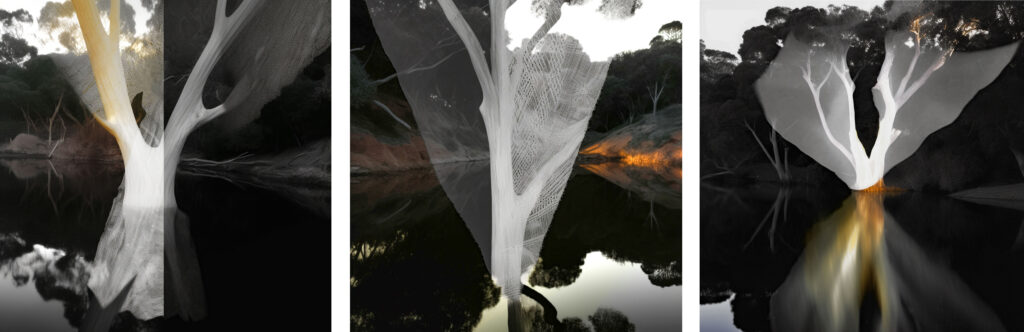

Plastic can be found everywhere on the planet. It’s estimated that up to 13 million metric tons of plastic ends up in the ocean each year and microplastic particles have even been found in human blood and lungs. This work, a blend of my own still life and landscape photographs with artificial intelligence, speaks to the intersection between nature and technology and the devastating impact of human activity on the environment.

Ghostly eucalyptus trees enveloped in sheets of clear plastic struggle to survive in a denatured landscape, serving to remind us of the urgent need to protect the natural world for future generations.

Ghost Gum Triptych recently won the Sustainability Category in the prestigious Australian art prize, The National Capital Art Prize.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CxK_bLwrc8W/

EMILY VAN ENGEL

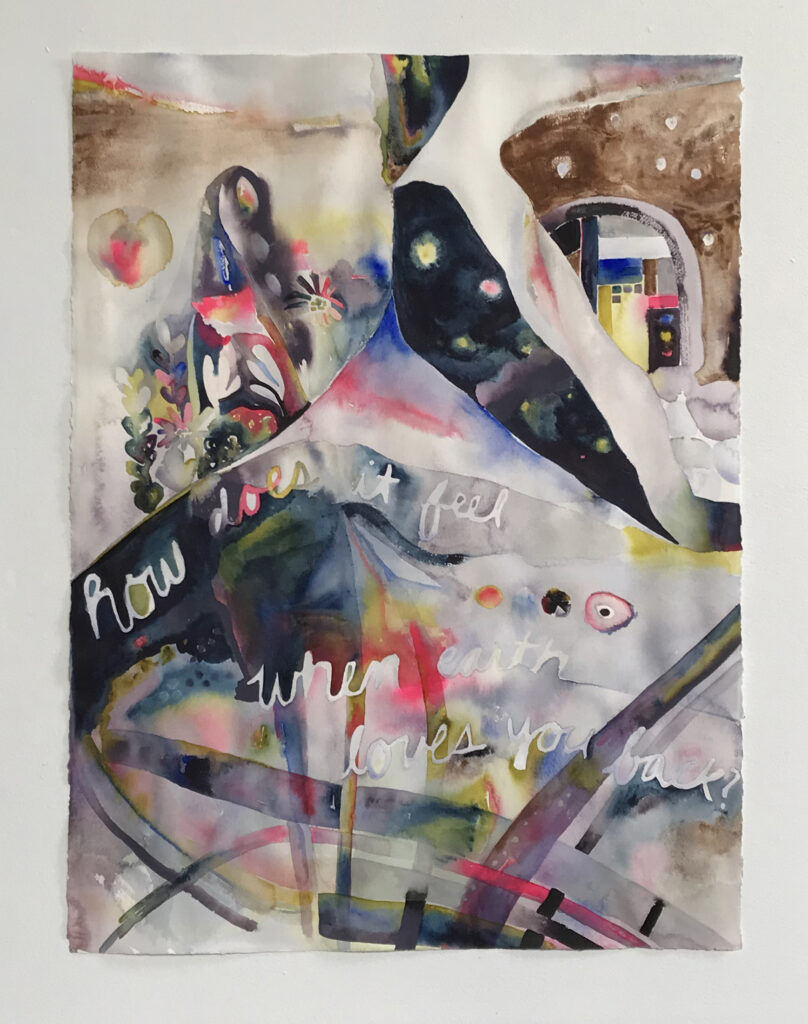

The current and looming impacts of the climate crisis have left so many of us anxious or depressed about the future. However, my art investigates what it could look or feel like to heal our ecological crises. I explore my hope through color, text and shape in my abstract watercolor painting. The palette is based on colors that correspond to how I aspire to feel about various aspects of living in society, including health, democracy, housing, ecological practices, and more. The phrase “another way is possible” adds specificity and conveys what I imagine and wish for ourselves and Earth. Formal elements that evoke threads and weaving nod to intersectionality and strengthening. Reaching for what it feels like to have a healed relationship with Earth is a way that I hope to offer an emotionally safe space for conversations about healing our ecological crises.

One of my goals with my artwork is to inspire change in imagination, perception and values around the climate crisis and our relationship with Earth. My intent with this piece is to move away from the shame that many of us feel when considering ecological crises, and instead to invite us to feel the unconditional love in our relationship with Earth as a starting point for healing. I chose the palette intentionally, as each color corresponds to how I aspire to feel about various aspects of living in society. In some areas I weave the colors of my palette together as a metaphor for the ways that what the colors represent – environment, health, racial justice, housing, and democracy – intersect and strengthen each other. I also include earthly imagery in the piece and work with watercolor as a further connection to Earth.

GRACE GROTHAUS

Sun Eaters uses custom electronics to visualize biodata as light. Here a grove of trees at the Toronto Botanical Garden are equipped with branches I created to enable people to both see and feel a tree’s “heartbeat”. The installation shows the electrical patterns unique to each tree, a constantly shifting combination of internal factors including a tree’s overall health, daily metabolic processes, and state of hydration. Their pulsing rhythms are also influenced heavily by external environmental cues such as time of day, season, and the lunar cycle.

At several touch stations visitors can hold the branches, which contain sensors that pick up the bioelectric rhythms of each tree. This installation aims to create opportunities for empathy across species and a means of seeing trees as unique individuals, similar to how we see ourselves and each other.

DEBORAH KENNEDY

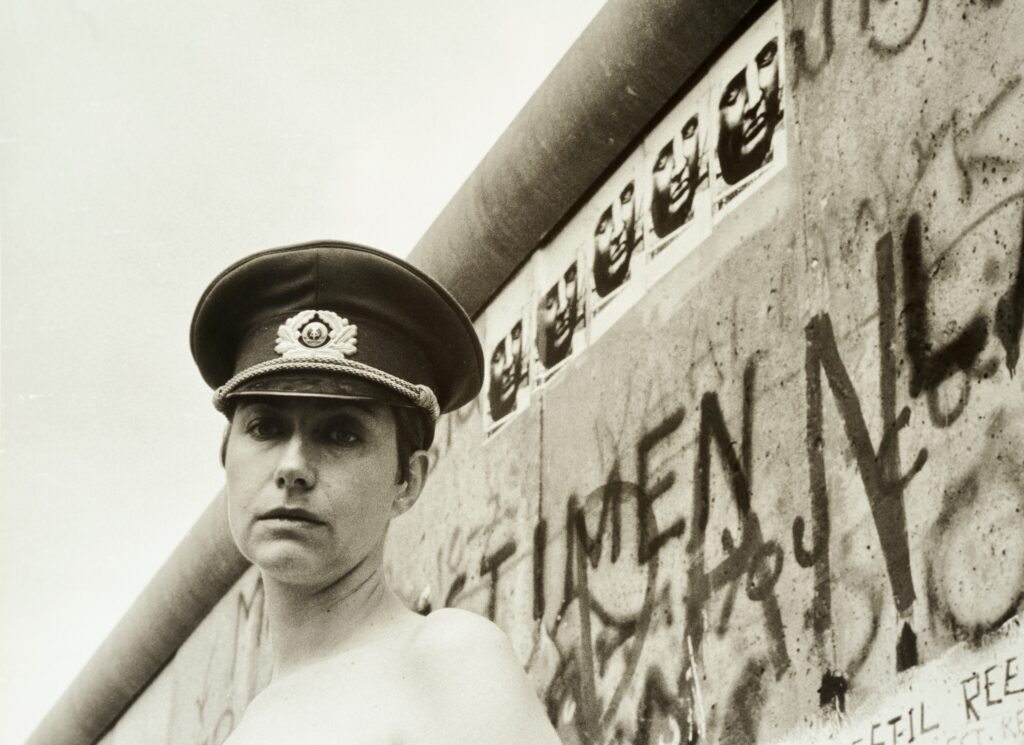

In 1989 I created the last series of large-scale installations on the surface of the Berlin Wall before Die Wende, including The Writing on the Wall, Hair/Haar, and Liberty Gate. While developing these artworks I also produced a series of photographs. One of these photographs, Walls Within: Berlin Wall, East Germany, was presented in The Billboard Creative: 2021. It is a self-portrait: I stand before the Wall with images of the Statue of Liberty’s face above me. These images were part of my attempt to install the artwork Liberty Gate. During these first efforts, the British military police seized my passport and threatened to confiscate it if I proceeded. I was able to finish Liberty Gate in the American sector of East Berlin where art and protest activities were tolerated. The completed artwork suggested an opening or gate in the Wall and featured images of the Statue of Liberty.

In my self-portrait, Walls Within: Berlin Wall, East Germany, I am wearing an East German military cap. This action was inspired by words an East German man shared with me: “Break down the enemy picture.” My bare shoulders suggest the vulnerability of the individual before the unrestrained power of a military police state.

The Berlin Wall fell six months later, astonishing the world. Soon after I reached home in 1990, the United States began building a wall on the border with Mexico. Today in 2023, our southern border is the site of a violent and shameful humanitarian crisis. Often migrants reaching the southern border are not only fleeing political danger but are also climate-change refugees, escaping homelands destroyed by droughts and severe storms. Our wall is also an environmental crisis, destroying native species and sacred sites. When will we stop building walls and recognize our intimate connections and responsibilities?

ISABELLA LA ROCCA GONZALEZ

Several years ago, for the first time in my adult life, I moved to a home where I could grow a garden. I’ve filled my garden with native plants. Native plants are beautiful, biodiverse, and resilient. Watering, herbicides, pesticides, and fertilizers are unnecessary. Natives are super beneficial to the local ecology, including beleaguered pollinators and wildlife.

A native plant garden is a political act. The homes in the area where I live, and in much of the U.S., are surrounded by lawns that consist of invasive grasses. They require watering, fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides. Pollinators and wildlife are treated as pests. Lawns are a colonialist practice that has decimated the polycultural ecosystem that existed in the precolonial Americas and is directly connected to the ethnocide of Indigenous people.

These images are based on photographs of native plants in my garden and of lawns on the road where I walk.

FERN SHAFFER

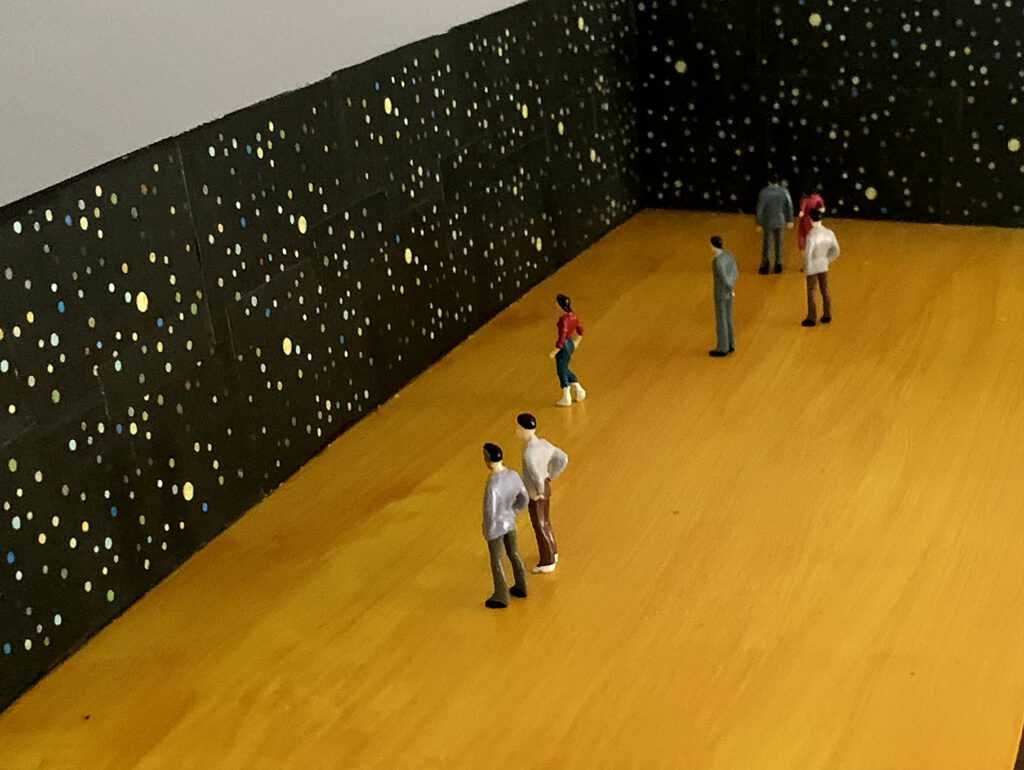

“1000 Moons” is about t/Time. It is about 80 years of my own lifetime and also about an infinitesimal moment of Time in the endurance of our planet. 80 years doesn’t even register in the eternity of the Moon’s cycle around our planet. However, this dual view of time, as a personal encounter, and Time as an eternal cycle are not the same thing. At this moment because of our global climate crisis and escalating political upheavals we have collapsed t/Time.

How long do we have left? How many generations will survive? How can our planet regenerate itself? Will there be enough t/Time? Began in 2020 at the onset of the pandemic and completed in 2023. This piece is painted in acrylics on individual black canvas of various sizes. When installed it can fill a 2000 square foot space.