‘Dear Ms. Pineda,

Thank you for writing your fearsome, enlightening book DEVIL’S TANGO.

We here in the states and the people of Japan and the whole world are fortunate that you responded to your dying friend’s request.’

TURNING 80

Turning 80 this fall represents turning over a new leaf in my writing life. Until recently, I have been recognized—if I have been recognized at all—as a writer of fiction, and as a theater-maker before that. My path took a sudden left turn in 2009 when I bought a plane ticket back East to spend ten days interviewing Jean Blum, a Holocaust survivor and activist who had helped undocumented people caught in the U.S.Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) dragnet, in the County Jail in Patterson, New Jersey.

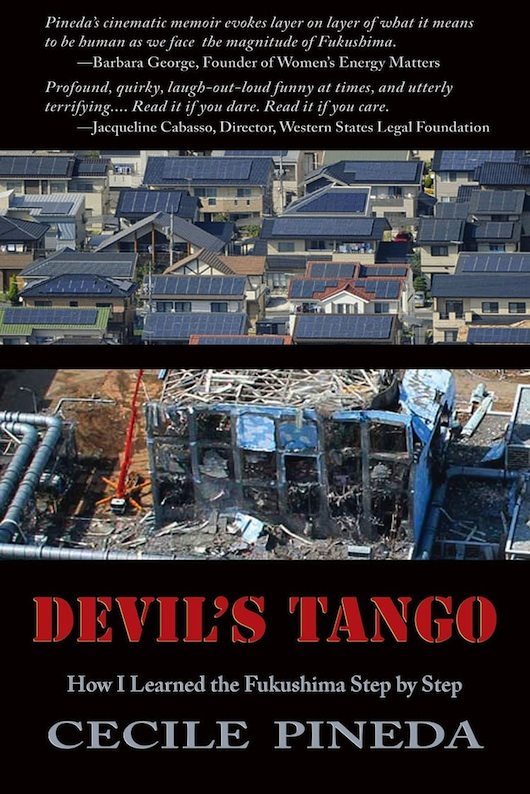

The fruits of my labors stretched to 32 pages, and when no major daily would carry it, eventually it found its way to publication in La Bloga where it is still archived. It was a good non-fiction apprenticeship for Devil’s Tango: How I learned the Fukushima Step by Step, published by Wings Press, San Antonio, on the one-year anniversary of the still unfolding Fukushima-Daiichi nuclear catastrophe on March 11, 2011. It joins a perhaps unusual category of books—books written by invitation. I did not intend to write Devil’s Tango. The concatenation of events: a dying friend’s request to me, and 13 days following his death, the explosions and meltdowns at Fukushima were the precipitating circumstances that gave birth to Devil’s Tango.

Below, three sections, numbers 2, 1 and a preface follow in reverse, perhaps perverse, order:

2. EMERGENCY

My neighbor is dying. Once he was on the bus to Mississippi, off to join the Mississippi Summer. He marched with Martin Luther King, Jr.

‘Give me a hug,’ he says to me shortly after learning his prognosis.

‘I need a hug, too,’ I tell him and I hold him tight.

He alternates between moments of great lucidity and hours of night terrors where his scrambled brain allows him at last to collapse into a chair facing the wall, waiting for a reprieve he hopes the dawn will bring. He knows he is dying. He has little time left.

‘This is an emergency,’ he tells me, his still blue eyes wide with terror. ‘Call the police.’

He’s too terrified to remain inside his apartment. Outside along the hallway I line up chairs where I sit with him. After some hours of negotiation, it’s clear nothing will do but to call the police. They arrive at 2 am. They ask the usual questions: do you know where you are? who you are? The deep philosophic questions we depend on our finest to formulate.

Judging from the name on her badge, one of these officers is a Latina. ‘El señor esta muriendo,’ I whisper. At once the tone changes. The questions yield to appropriate negotiations. The cops promise my neighbor that, come morning, his daughter will return to comfort him.

He summons me for a visit one last time. His eyes are shining. He sits enthroned in his chair in his bathrobe and underwear.

‘This is an adventure! I’m going to write a book,’ he announces, slapping determined hands on his lap. ‘Here’s how it starts:’ He gives a sentence or two. ‘That’s Chapter One. Will you edit what I write?’

‘Now,’ he says to me, ‘now you, Ceil’—he always calls me Ceil—’you always have things to say about life on the planet; you need to write a book, The Book of Living and Dying. Will you do that?’ He waits, all expectation. I’ve just come to the end of a five-year project but how can I thwart such compelling faith?

‘Warren,’ I say, ‘I don’t know if I can do it, or if I will do it, but if I can do it, and I do do it, I promise I’ll dedicate it to you.’

He smiles the smile of a mollified child. ‘Ceil,’ he says, ‘this is fascinating!’ He means death. Dying is fascinating. ‘Don’t you want to live long enough to see how it all comes out?’

‘Dying takes a long time,’ I tell him, laughing. He has the grace to laugh with me. We are children playing with the red ball of death. We toss it back and forth. ‘I’m going to write about it,’ he says. ‘I starts like this ‘

He lies in his old man’s bed. More and more he sleeps. Someone comes in to nurse his last hours, to turn him over in the sleep from which he will never awake. Once he marched alongside our great prophet, Martin Luther King, Jr. It ends like this.

Thirteen days later the reactors at Fukushima will explode, scattering deadly fallout over the entire planet. You know what this means. You know the fall-out plume will soon blanket the northern hemisphere. You know it will contaminate the food chain, on land, and on the sea. You know it will taint the soil, and the water, and the air you breathe. You know from now on, it will taint everything you drink and everything you eat.

1. HABITABLE ZONES

We picked out planets that are just the right size—between the size of Earth or twice that—and all are within the ‘habitable zones’ of their stars, at distances where there’s the best chance for liquid water—and possibly life—to exist.

— Dan Wertheimer, space sciences lab astrophysicist

There is no place more wonderful than this. There is no place more marvelous than here.

— Milarepa

Starry night. All along the horizon, telescopes rotate, staring at the night sky: the Atacama Desert, where the skies are transparent like no other place on earth, free of the pollution of city lights, and of temperate zone moisture.

The human race is looking for planets. Hungry for planets in our own image, in the image of Gaia, of Earth. Planets near enough yet far enough from their distant suns not to burn up, not to freeze. Planets which show signs of water in their atmospheres. Planets that revolve around the maybe 50 billion stars in the local galaxy, in the neighborhood we call the Milky Way, and in the narrowest possible tranche of it, 1,235 planets have been sighted that correspond to such spacial parameters, and of those 1,235, 86 stand out, 86 which answer within reasonable limits to those conditions: sufficiently distant from their suns (but not too distant) to entertain the possibility of water.

Imagine 86 watery planets, each with its own orders of life: its own set of one-celled organisms, of invertebrates, of phyla inherited from a primordial past, of the first cone-bearing trees, of the first flower bearing plants, of mammals, of insects, of trees, and shrubs and flowers. Imagine 86 planets with their own hereditary, evolutionary lines culminating or perhaps on the way to culminating in sentient, intelligent beings with appendages to hold tools, to compose music, to create dance, with tongues to bend around the syllables of languages structured entirely other than any Earthlings can begin imagining. Eighty-six planets with their own dynasties of composers, choreographers, writers, poets, singers of songs. Take all the sounds of all the languages of 86 planets, and all the sounds of all the music of 86 planets, meld them together, imagine the chorus. Now turn down the volume to a whisper: the whisper of the sounds made by the sentient beings of 86 planets. That is only 1/600,000,000th of the sounds of all the neighborhood galaxy’s planets, and, of the universe’s, a fraction so unfathomable human cognition cannot imagine it.

But this one, this Earth, this Gaia is the one you have. This one, and only this one. Its rocks, its fossils, palimpsests of times more ancient than time, its petroglyphs of a mankind more ancient than language, more ancient than writing. Its horsetails and ginkos, survivors of an unfairytale age of dragons, of cone bearers, of spore bearers, of molds, of microorganisms, of nematodes, of annelids, of the lowliest of beings without which none of our living, none of our songs, or our musics, or our dances, or our writings or our tongues could ever have been possible.

This Gaia is all you have.

* * *

Devil’s Tango did not teach me to dance. It started with a total car wreck from which I escaped unscathed except for a bloody nose and a deviated septum. I didn’t want the wreckage to remind me: I couldn’t get it towed to the junkyard fast enough. It ended with a broken ankle on New Year’s Eve, 2011. You may ask was I boozing, cutting too many quicksteps, but I hate to disappoint. I was hiking. I “let go” after 9 months of feverish work learning the TANGO’s 130 steps. I was NOT PAYING ATTENTION.

It’s not easy for you, or me, or anyone to PAY ATTENTION to the consequences of the nuclear energy cycle. Why? Because you can’t see radiation. And you can’t tell if your cancer happened because ten years earlier you were in a place it would have been better for you not to be. You can’t tell if your stillbirth happened because your tiny fetus couldn’t live in an irradiated world. And you can’t tell if the child born to you 10, 25, 50 years ago, and who is a “different” child, affected by autism, or attention deficit disorder (ADD), or any number of unidentified syndrome complexes, was born different because the air was contaminated from ‘testing,’ or because the milk that year was tainted from fallout.

You can’t see fallout, you can’t tell when you’re eating strontium by the spoonful. It’s invisible; you can’t see it, feel it, touch it, hear it; you can taste it only sometimes—when the fallout is particularly dense as a metallic taste in your mouth, which any number of people reported this past year in places as far apart as Seattle and Arizona. In a world that enshrines surfaces, the industry thinks invisibility is a sure bet you won’t ever find out.

To say that corporate enterprise has abrogated your right to ask questions, to raise objections, or to expose malfeasance tells only half the story. Corporations are not people. We are people, and until we learn to protest en masse, until we make it impossible for corporations to continue stripping the planet, they will hijack our earth, and make all living things expendable.

That means you. That means us.

Writing this book taught me that I was every bit as asleep as anyone else. It woke me up. I hope that in reading it, you will want to join me, in the streets, in your town hall, in your council chambers, at your local reactor’s gate, and wherever like-minded people bent on defending the left-over tatters of our planet meet. Abbie Hoffman once wrote:

‘Democracy is not something you believe in or hang your hat on, but something you do. You participate. If you stop doing it, democracy stumbles and falls. If you participate, the future is yours.’

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 5, ATOMIC LEGACY ART

Published August 2012