Location: Vancouver, Canada

I. FINDING HOME

IN THE FIRST PART OF THIS TWO PART EXPLORATION OF Ecological Art in Canada, I gave an overview of the context in which much of such art is practiced, and explored some works and practices. In this second part, I have chosen to expand on the central idea of relationship to the land, relationship with place as informing the work. First, however, I want to expand on the context in which these works arise.

As I explained in that previous essay, the work we make arises from where we are. The Canada we have today is a country in which the colonial practices of resource extraction and development still take precedence. Canada officially ceased being a colony of Great Britain in 1847, but remained under the governance of Britain as the Dominion of Canada until the Canada Act of 1982.

Why this seemingly unrelated bit of history is important to this essay about ecological art is that the government of Canada, rather than writing new laws governing industry and land use, simply adopted those already in place under the imperial system. And one can readily understand why. People had built their empires under these laws and wished to maintain and grow these. Such laws to this day make it very easy for corporations and industry to access pristine habitats for resource extraction, since the original intention of the colonizing of the land – as I mentioned in the previous essay – was to take the best from the lands and waters and either send it ‘home’, or export it for gain.

Industrial uses of land and waters continue to take precedence over all other uses, and ride roughshod over the interests of the indigenous First Nations peoples. In Canada, land ownership is based on British Common Law, which means that private land ownership is not in fact land ownership – it is in fact the granting of rights by the Crown to use the surface of the land. (Real estate, or ‘real’ property, consists of buildings, etc on that land.) The Crown (the province) owns the mineral rights in perpetuity. Should industry find oil, gas, or other minerals, these can be exploited regardless of the desires of the general population and those of the owners of surface use rights (titular owners) should the government so decide. This means that provincial governments (the Crown) are in effect the landlords of industry, whose practices historically filled government coffers via taxes and leases.

Canadian philosopher George Grant in a 1969 essay observed that the only history for settler culture in North America is that of subjugation, particularly since settlers have no pre_industrial history in this place to connect them with the land. He reasons that lacking this sense of ourselves beginning with the land, of our wellbeing and identity tied to the health of the land itself, we can have no deep sense of belonging. In Grant’s words, ‘That conquering relationship to place left its mark within us. There can be nothing immemorial for us except the landscape as object.’i

Within Canada’s settler culture this unease has created a continual questioning of both our identity and what I will call place relations – the nature of the relationship one has with a place, and the role of the other-than human world in that relationship.

In a sense then, we are ghosts on the land here, longing for belonging. Iconic Canadian writer and literary critic Robert Frye took Grant’s comments further, saying we are, ‘… Cartesian ghosts, caught in the machine we have assumed nature to be.’ii In short, we have trouble behaving as if we belong to this place, and the systems put in place and embedded over time do not nurture belonging. We are doubly disconnected. Not only are we unsettled by being a settler culture, roots still drinking deep from exploitation and the belief that home is elsewhere, we are, as members of a great Western tradition, Cartesian ghosts, divorced from being a part of the land and of a nature external and alien to the human.

Artist Sandra Semchuk asked the question: ‘How do we, living here in Canada, having come from elsewhere, connect strongly with where we are? Because unless we can have that kind of connection, how can we be committed to where we are?’iii

And in the now famous words of U.S. writer and early environmentalist Aldo Leopold, ‘We can be ethical only in relation with that which we can see, feel, understand, love, or otherwise have faith in.’ iv

Several artists in Canada embody the intention of Semchuk’s question and Leopold’s statement in their practice, seeking to develop and foreground these aspects of place relations, while at the same time striving to discover their own sense of relationship with, and belonging to, the land. Such practices, I believe, also hold the promise within them of engendering the same sensibilities in the community at large. Given the story of Canada, it is not surprising that artists here should undertake such a quest – a quest and enquiry that seem particularly urgent, given the current state of human-world relations. In fact, in striving to move away from the legacy of that ‘conquering relationship to place’, I believe that the works of many of Canada’s artists offer a particular perspective, as we have lived so long and so intimately with these questions, coexisting with an awareness of an uncertainty of our place in relation to our immediate environing world.

II. MARLENE CREATES

THE INTERCONNECTED QUESTIONING OF IDENTITY AND place relations has for decades been at the core of the work of Marlene Creates, who has long been known for her works exploring place, memory and transience. The tracing of the memories, the narratives, of oneself, or a community, on and with the land is a kind of seeking to understand connection, and how connection comes to be, through an attentive engagement and a mapping process that is often composed of images. Seeing the images, we become witness and participant.

The tension might hold within it the split between longing and belonging. It is easy to take this at face value, to equate it, quite correctly, with the obvious split between a colonizing settler culture and the land. But there is something more going on here. In commenting upon her work and process in 1988 Creates expressed the belief, “That there needs to be a reconnection between what is experienced as culture and what is experienced as nature.’v She is concerned with her interactions with the agency of the nonhuman and the traces of that interaction; with where they meet, blend, and where there is distance between them.

Her works are collaborative with land, grasses, trees and water. In Sleeping Places, Newfoundland (1982) a series of photographs documents the traces of Creates’ body on the land, in the long grasses where she slept on a walking tour. Her most recent work is a deep collaborative interchange with the six-acre piece of land where she now lives, coming to know it ever more intimately through the process of being with, listening, walking. She speaks of coming to know individual trees, of the ever-increasing depth of relationship between self and place. Recent and ongoing work Larch, Spruce, Fir, Birch, Hand, Blast Hole Pond Road, is a series of photographs of the hand of the artist resting on different trees, where the sameness of the hand reveals the individuality of the trees. The gesture demonstrates acknowledgment of both difference and relationship.

III. PETER VON TIESENHAUSEN

ONE OF CANADA’S MOST WELL KNOWN ARTISTS, Peter von Tiesenhausen lives and works primarily on the family spread – a large farm in North Western Alberta inherited from his parents, and far from the nearest city. This farm sits squarely on top of one of the biggest deposits of natural gas in Alberta, known as the ‘deep basin’. Prior to beginning his practice as an artist, he made his living running heavy machinery, working in the oilfields, taking out the forests. He has seen first hand, and participated in, the destruction that the industry brings.

Since pursuing his art practice on the family land, von Tiesenhausen remarks on the number of times he’s been visited by oil and gas executives, wanting to write him a check for accessing the gas under the land. The province of Alberta owns the oil and gas beneath the surface, and can at any time allow extraction – so long as von Tiesenhausen is compensated. His response has been to copyright the land itself as an ongoing artwork. While this does not grant him any additional rights to the land, it does up the cost to oil and gas companies of doing business. In his own words, ‘Now instead of maybe $200 a year for crop losses, we’d have to be paid for maybe $600,000 or more in artistic property disturbance.’vi To date this keeps the oil and gas companies at bay, since they want to neither pay the price, nor bring the practice of land and livelihood copyright to the attention of the greater public through a court challenge.

I feel comfortable calling this a form of activist art, but it is not overt confrontation, rather it is taking a stand, out of love, and care for the land itself, for its own sake. As such, it resonates with other actions and projects undertaken by artists in Canada, such as the Ut’saam/Witness Project I wrote of in the first part of this series. As I wrote then, much environmental art practice in Canada is about finding ways to preserve the lands and waters, to keep industry at bay and to safeguard habitats in perpetuity.

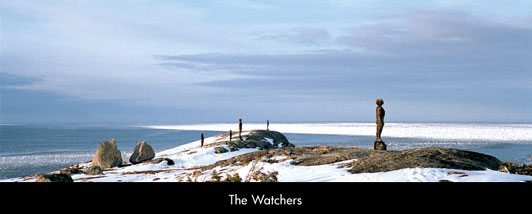

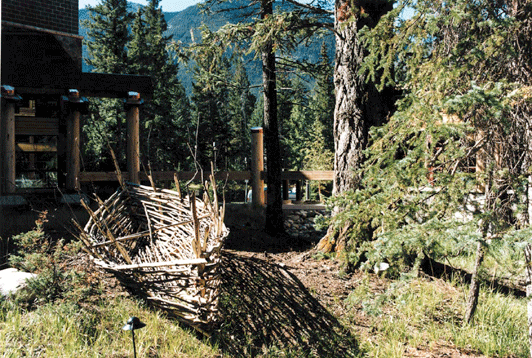

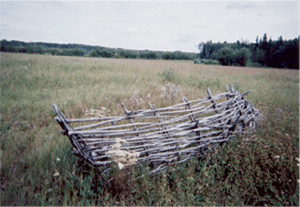

About his landworks von Tiesenhausen is remarkably silent. What he does readily speak about is the magic and beauty of the land, of the venerable trees, and his respect for both. In his work, his interest is in letting the place speak to him, and in letting the environment ‘have a say’. He often arrives to do a work not knowing what he will do. It is about listening. And this is how he approached the commission from the Vancouver Park Board to create an ephemeral and a semi-permanent work for one thousand acre Stanley Park as a part of the Stanley Park Environmental Art Project. In fact, the semi-permanent site work is called Listen – an acknowledgment of process and the voice of the place itself in the work, as well as a reminder to all who visit.

Von Tiesenhausen says he does not want to tell people what to think, he wants people to experience, to see anew, to recognize that the lands and waters where we live are full of magic, meaning and story – and to experience a healthy awe, as we should, in the face of this.

IV. DEER CROSSING THE ART FARM

SITUATED ON A FIVE ACRE PROPERTY ON BRITISH Columbia’s Sunshine Coast is a recent addition to the small list of Canada’s organizations that work with art, community and environment. Deer Crossing the Art Farm has just completed its third summer of programming. It offers residencies, workshops in arts and sustainable building, and also an annual two-day festival, Synchronicity, which focuses on collaboration among disciplines and on community building. Workshop focuses include cob building, water systems, and composting toilets. They also host the Art Farm Hub, which, in their own words ‘provides artfarmers with a physical gathering space at their disposal through the art farm season for reflection, dialogue and collaboration in the name of change. Along with a gathering space, the hub also doubles as a laboratory (art farm lab), a physical space for artfarmers to explore and develop their own experimental work and ideas.’vii

Works also invite collaboration with the land. The first of these on the site is the Laurel Spiral. The Spiral is connected to an ambitious long-term vision for the project, a large part of which is that it be ‘a place of encounters with nature, with the inner self, and with others’. (The website has a wonderful nine-page PDF plan of this vision available and I encourage viewing it. It is linked from this page: http:// www.deercrossingtheartfarm.org/node/353 )

Another part of this vision is the development of performance works that actively collaborate with the land, which are grounded in the land. An interesting aspect is the desire to tour performances in such a way as to include the local bioregion wherever the work is performed. When this is ready to go, I look forward to seeing how the voice of place will speak through the work as it travels.

In a conversation with co-founder Chad Herschler I asked about their motto – ‘Art + Nature = Transformation’ – and about the Art Farm. Chad explained that it is the belief of the Art Farm group that the experience of being on the land, with the other than human world, is transformative in itself; that a reflexive inner space is created through this contact which can lead to revelation, however subtle. It is also their observation that art can have a similar effect, and that when one puts the two together this is enhanced. The goal is that time spent in the natural creative space of environment, along with the intended creative space of art – both subtly dialogic – will lead to better, more attentive and caring human-world relations. It is certainly the case that Herschler has seen significant transformation come about in people who spend time with the land, mindfully, which observation resonates with the beliefs and practices of Ecopsychology.

They are also mindful of the history of the land that is the physical home of Deer Crossing the Art Farm. It is an experienced five acres, in that it has to date been commercially logged three times. It lies within traditional Squamish territory and the community at the Art Farm is working to develop a rapport and hopefully future collaboration with the Squamish people. Stay tuned.

V. CONCLUDING COMMENTS

THIS IS FAR FROM AN EXHAUSTIVE EXPLORATION of artists, works and projects, intentions and ideas within and above art and ecology in Canada. Because of length, I chose in this second essay to expand on ideas brought forward in the first and to focus on in a bit more depth on specific artists and one project.

These share a common intention, and demonstrate an eagerness to invite the land to speak and to attend, listen, to its voice. Place itself is acknowledged as an active collaborator, and by extension, such acknowledgment foregrounds the awareness that place always informs us, is always here with us and within us.

This acknowledgment also brings awareness that identity involves more than simply human cultures – names and stories – laid upon a place, upon the lands and waters. It reveals that identity arises from the place itself, from the subtle interchange over time between human intention and the land. It is collaborative and it is dialogic. It is a subtle activism of the heart, standing firm against ‘that conquering relationship’.

Please do visit the sites below.

Marlene Creates http://www.marlenecreates.ca/

Peter von Tiesenhausen http://www.tiesenhausen.net/

Deer Crossing the Art Farm http://deercrossingtheartfarm.org/

Notes

i Grant, George (1969) In Defense of North America, p.17

ii Frye, Northrop (1977) ‘Haunted by Lack of Ghosts: Some Patterns in the Imagery of Canadian Poetry’ in The Canadian Imagination, p. 28

iii Semchuk, Sandra, from her talk given at the SongBird project’s 1999 Living City Forum in Vancouver Canada

iv Leopold, Aldo (1966) A Sand County Almanac – Part IV, ‘The Land Ethic’

v Marlene Creates in her comments on her 1989 work The Distance Between Two Points is Measured in Memory source: http://www.marlenecreates.ca/works/1988distance.html Accessed September 6th 2010

vi Peter von Tiesenhausen as quoted by Gordon Jaremko in the Edmonton Journal, ‘Opposition to Drilling Elevated to an Art form’ Published 2-27-2006

vii Source: http://www.deercrossingtheartfarm.org/node/353 Accessed Sept. 6th 2010

All images were sourced from the about artist/project websites

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 2, GLOBAL IS PERSONAL

Published December 2010