Location: Portland, Oregon

ARTIST’S NOTE: Essay is adapted from my artist’s book Castor and Sapient, 2020, for Science Stories online exhibition, University of Puget Sound. Collaborating scientist Peter Wimberger.

DETAIL, Castor and Sapient, 2021

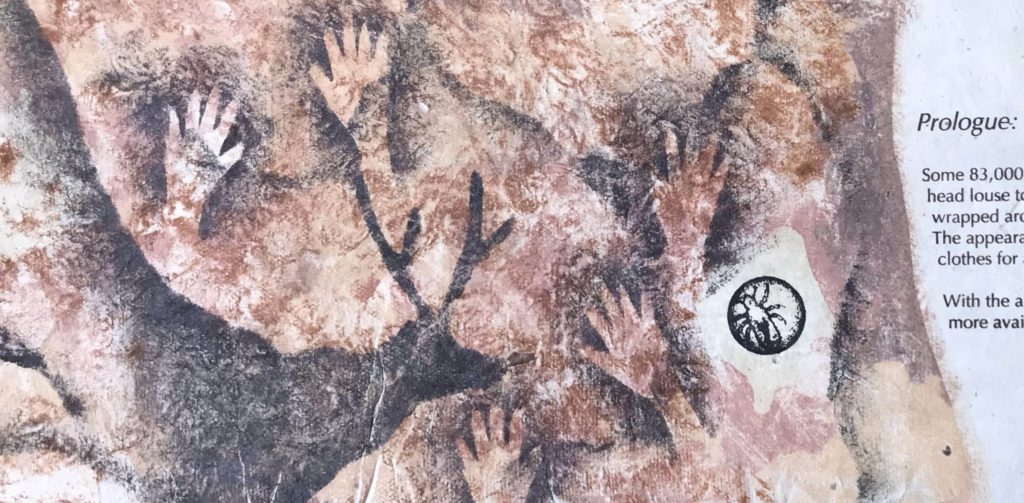

I. PROLOGUE: A LOUSE IN MY LADY’S BEAVER CLOAK

SOME 83,000 TO 170,000 YEARS ago, a species of louse split from a human head louse to occupy a new niche that originated from a piece of gathered plant fiber or animal pelt wrapped around a person, which left the original louse behind on our human heads. The appearance of this new louse suggests that our ancestors had been wearing clothes for a long time.

With the arrival of agriculture, flax, wool, silk, and cotton clothing became more available, and furs and skins became associated with people of wealth and status.

Fast forward to Medieval Europe. Sumptuary laws codified the use of furs according to social ranks. Beaver fur-luxuriously soft on the skin and excellent at holding a shape when felted-was the choice material to line garments and armor, and for making elegant hats. By the early English Renaissance, beaver-the world’s second largest rodent-was becoming so rare that Henry VIII elevated beaver fur to ever-higher status through four separate Acts of Apparel. The European beaver, Castor fiber, finally became extinct in Britain sometime around mid-1500s, and was so diminished in continental Europe that beaver pelt trade all but stopped by 1600.

The hunt for beaver pelts then turned west and crossed the Atlantic, as trade between early European colonists and Indigenous Peoples flourished. In exchange for pelts from the Algonquin, Iroquois, and Innu traders, the French, English, and Dutch offered tools, weapons, and other ‘modern’ goods; but they also brought along new plants and animals-including the now ubiquitous rat-and deadly diseases.

BEAVER RANGE MAP, Castor and Sapient, 2020

By mid-1600s, a mere 30 years after the establishment of Plymouth Colony, the North American beaver, Castor canadensis, became scarce in eastern New England. After the Seven Years’ War and the War of Independence, Britain and the United States-the two remaining competitors for beaver pelts-pushed west towards the Pacific Ocean as beaver populations along the Eastern seaboard of North America became depleted. The United States considered the lucrative trade as the major economic objective while Britain, through Hudson’s Bay Company, set out ‘to destroy as fast as possible’ the rich preserve of beavers as a disincentive to American settlement further west.* The beaver population of North America dwindled from an estimated 60-400 million prior to European arrival to near extinction. Extensive beaver-built webs of waterways-of ponds, marshes, and meadows-that supported complex ecosystems and aquifers were replaced by far simpler, more meager, free-flowing rivers and streams that we now liken to ribbons.

At almost 20 times the cost of other hats, the beaver hat was once a display of affluence and power, and beaver fur the subject of erotic poems and cautionary ballads. But after hundreds of years, fashion trends finally moved on, leaving behind devastated beaver populations and ecosystems. Coupled with the dwindling supply of timber in the American East and Midwest, logging, along with mining and grazing, replaced the beaver as the economic engine of the American West.

So it was that we said to all that the planet encompasses – all its plants, animals, and minerals – you belong to us.

* From the journal of George Simpson, Governor of Hudson’s Bay Company, 1824-1825. Simpson’s plan later came to be known as the fur desert policy.

II. TWO RATS AND A WATERWAY IN A GARDEN UNDER THE DOUGLAS FIRS

EVEN AS BEAVERS were being hunted to near extinction, a spot of land at the confluence of the Columbia and Willamette Rivers-home of the Multnomah, Wasco, Cowlitz, Kathlamet, Clackamas, Bands of Chinook, Tualatin, Kalapuya, Molalla, and many other tribes-was being so rapidly cleared of trees by European colonists that it earned the moniker Stumptown. It was officially incorporated as Portland in 1851. A few decades later speculators carved up southwest Portland, and West Portland Park became its first housing development in 1889.

The land for West Portland Park was clearcut, the timber sold, a rail system built; but the real estate scheme was a bust. By the early 1900s, the area was filled with dairies, orchards, and flower and tree farms. Vintage photographs, housing records, and oral histories paint a portrait of a neighborhood with a few houses among acres of second growth Douglas firs. Tall, straight, and fast growing, Douglas fir was valued for telegraph and telephone poles, and railroad ties. By late 1960s, the tree and flower farms had reverted to second-growth wildwoods and then, lot by lot, developers started to convert these woods to residential housing.

Our house was built in 1986 on a parcel of second-growth wildwood in West Portland Park. Save for four Douglas firs and three alders, the land was cleared and sod was laid down. When we purchased it in 1991, the yard was a quarter acre of tidiness with velvety grass, round bushes evenly spaced along the borders, and one ornamental tree on each side of the property. Of the wildwood, only the four firs remained.

‘The grass has to go!’ was my battle cry as I set to work on the south side yard under the stand of firs. I have always dreamed of living in the woods, and if that was not entirely practical, I took this opportunity to bring some of the woods to me. I replaced the grass with a mix of native and non-native trees, shrubs, and ground-cover. A few years later, I installed a drip watering system. Over the next decade, I systematically removed the remaining grass, similarly replaced with trees, shrubs, and ground-covers, and finished installing the drip system.

DECISIONS: The easy decisions first- I removed about 20 sq ft of bamboo in 2021 and potted up a few rhizomes so that I could continue to enjoy them while allowing native plants to do their magic. Several sword ferns have been growing under the thicket and they really started to thrive once the bamboo was removed. I have added other volunteer natives that came up in other parts of the yard, they’re too small to see here yet. Several smaller non-native ornamentals have been put in pots as well.

With the whim of a hobbyist and the goal of conserving water and energy, I learned just enough to do what needed doing. Only coincidentally, because I wasn’t concerned with neatness and design, did I happen to create a garden that also provided shelter for wildlife and generated much needed organic matter. Over the decades, many birds, squirrels, slugs, salamanders, and snakes made their homes here; and the occasional deer and coyote also wandered through.

But I had, regrettably, chosen the evergreen Vinca for my ground-cover, and it grew. And grew and it swallowed the drip system and many of the smaller shrubs. Critters dislodged drip lines, mineral deposits from city water clogged the drip heads, and many plants struggled along. Then in June of 2020, a descendent of a colonist rat executed the coup-de-grace by chewing through an arterial line, creating a small lake in one spot but no water downstream. Finally, I started to dig up the Vinca to locate the damage. My audiobook Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer-scientist and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation-arrived just then, so I listened as I dug.

BARBERRIES: I planted 4 Japanese barberries in 1991 and have enjoyed their burgundy leaves and ruby-like berries in the fall and winter. They’re absolutely carefree and drought tolerant, but have become invasive in some eastern states and are popping up in forests and wildwoods, pushing out native vegetation. It wasn’t too hard to decide to pull these 4, but it was hard work – it took me 8 days to dig up these root balls. I am still stewing over what to do with them. (My size 9 shoes for size comparison.)

Kimmerer’s memoir and exploration of the reciprocity between the land and all that live upon it was a revelation. Had I read her words sitting on my sofa, instead of hearing her gentle voice while digging in the dirt, would Braiding Sweetgrass have had the same impact? I don’t know, but her teaching came at the right moment and it started a profound transformation in my garden and my art practice.

In these 2 years since, I have continued to study and research ecology and agriculture in the home garden through books and the Oregon State University Extension Master Gardener Volunteer Program. I started to understand how plant choices aren’t just about how much water, light, nutrients, and efforts they require, but also what they provide both below and above ground; that they work with a whole community of organisms in the soil, exchanging water, nutrients, and oxygen. Together, they build soil structure to provide shelter, help retain resources, and make growth and renewal possible. These plants also provide food and shelter for a whole host of herbivores above and below ground who had co-evolved to overcome the plants’ defenses to avoid being eaten.

These evolutionary strategies have led to some exclusive pairings-for example, the monarch butterfly and milkweed, or the Oregon silverspot butterfly and the early blue violet. While insects add to our aesthetic enjoyment of the garden, they are also beneficial predators and pollinators, and are life itself to birds who rely on them for sustenance. Even those who survive on generalist diets, they do not gain the same nutrients and calories from introduced species, so they have to work harder to meet their needs, and often their needs aren’t met.

KATYDIDS: In an effort to get to know my neighbors, I have been paying more attention to insect life, documenting and researching what I see. I am inspired by Dr. Doug Tallamy’s tally – from a webinar he gave in 2021, he has counted 900+ species on his 10 acres since he began keeping track. Pictured are two different stages of Scudder’s bush katydid nymphs on my daylily.

When we garden, we enter into this community. And we are learning that if we do so without considering this existing reciprocity, we interrupt this bond — when we add an exotic plant, it may not be providing food, or it may try to exclude other plants in their vicinity; when we remove a native plant, those that depend on it will suffer; if we remove organic matter like fallen leaves or apply chemical fertilizers and pesticides, we break the cycle of reciprocity and the soil degrades, losing its ability to support life.

With the native milkweed removed for being a ‘weed’, monarch populations plummeted; many gardeners are now re-introducing milkweed into their lives, hoping to reverse this trend. The Oregon Zoo is active in silverspot conservation. Jenny Woodman of the zoo foundation says: ‘I understood why native plants were important on a philosophical level, but now I see the reality on the ground. Silverspot caterpillars rely on early blue violets to complete their life cycle, but their landscape and ecosystem are so dramatically altered that their survival is imperiled. I want to help before creatures and their habitats are on the brink. I want to listen to the wild world, because our fates are intertwined.’

If we consider the plant+soil+organisms a family story, a gardener who arrives and breaks up the union would be the antagonist in this drama. So it must be that when we garden, we respect the existing bonds of species, be it soil bacteria, salamanders, fungi, plants, insects, birds and any of the larger herbivores or predators that still roam our urban and suburban spaces.

So I, born in a year of the Rat, ask the Douglas firs, Oregon grapes, ferns, trilliums, salals, and many more: will you accept me into your community, to work alongside you, to share your bounty, to enjoy your company?

III. BEAVERS IN OUR MIDST

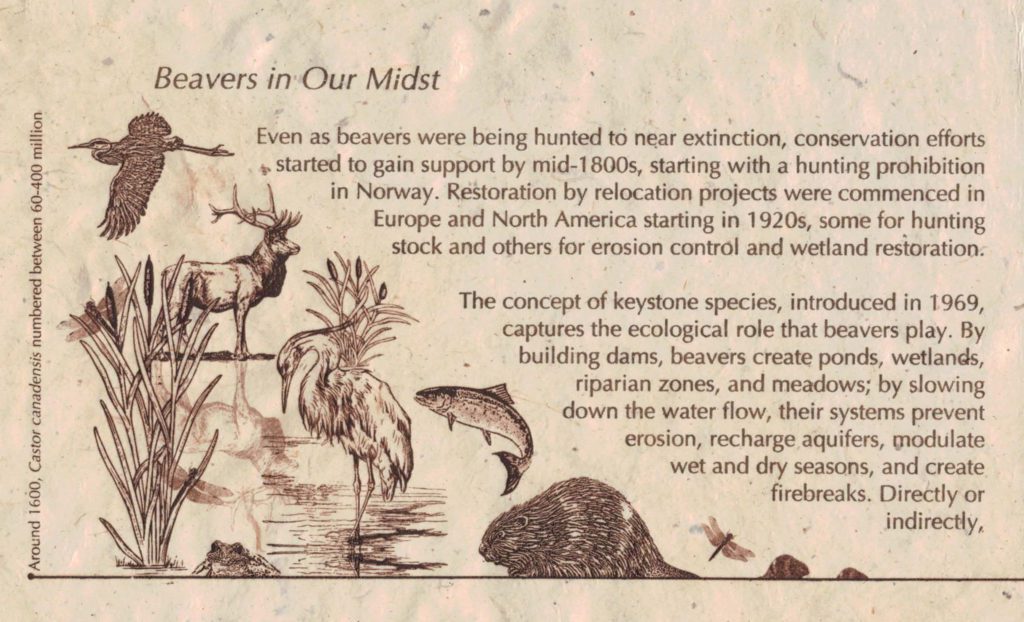

EVEN AS BEAVERS were being hunted to near extinction, conservation efforts started to gain support by the mid-1800s, starting with a hunting prohibition in Norway. Restoration by relocation projects were commenced in Europe and North America starting in 1920s, some for hunting stock and others for erosion control and wetland restoration.

DETAIL, Castor and Sapient, 2021. The graphic represents the precipitous decline of the estimated beaver population from prior to Europeans arrival to the beginning of the 20th Century.

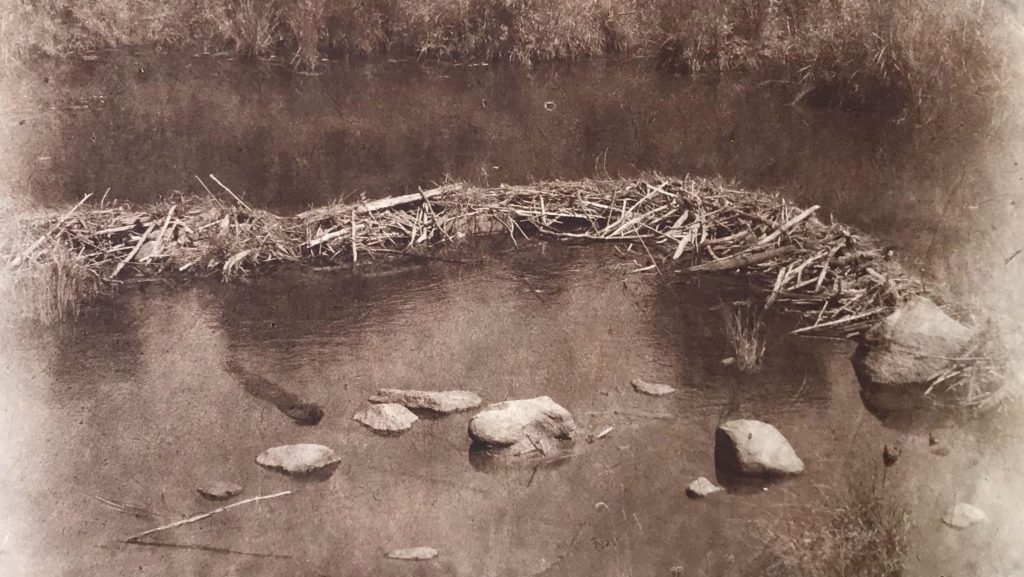

The concept of keystone species, introduced to ecology in 1969, captures the outsized role that beavers play. By building dams, beavers capture sediments, improve water quality, create ponds, wetlands, riparian zones, and meadows; by buffering the water flow, their systems prevent erosion, recharge aquifers, modulate wet and dry seasons, and create firebreaks. Directly or indirectly, they support an ecosystem rich with fish, aquatic plants, amphibians, insects, birds, and mammals all in a grand entangled web of relationships, a macrocosm to the microcosm of our gardens. Humans are also the beneficiaries of beavers’ accomplishments. If we enjoy outdoor activities such as hiking, swimming, fishing, hunting, we are playing in beavers’ world. Even in our human-built world, when we water our fields and gardens, or simply want clean water to drink, we can thank beavers for their millennia of work.

Restoration by relocation has continued to gain momentum, and after a century of different approaches, Castor canadensis populations are recovering from near extinction. But during the same period, the US human population has more than tripled, leading to increased human-beaver conflicts. When beavers build dams and make homes in culverts or irrigation ditches, humans find small lakes in roads, fields, or basements or maybe no irrigation water. Beavers have lost most of these conflicts, but humans have found themselves repairing the same damages repeatedly as new beavers moved in. Until finally, we began to see that we are neighbors, and we need to see our neighbors’ perspectives and learn to get along. Conflict resolution now goes hand in hand with restoration and conservation efforts.

DETAIL, Castor and Sapient, 2021.

The Methow Beaver Project may be the most ambitious beaver restoration by relocation project in the United States. The Methow River Basin in northern Washington State drains into the Columbia River and the Methow Beaver Project has been relocating beavers, mediating conflicts, restoring the watershed, and training restoration professionals since 2008. Its success is built on an approach of releasing bonded pairs or entire families in the fall. While a single beaver may wander off in search of a mate, a bonded pair or a family moved to a good pond or stream are happy to settle in and get ready for winter.

In hindsight, this concept seems obvious-that keeping families together in a positive environment benefits both the individuals and the community. This rational empathetic approach of understanding the beavers needs and collaborating based on both their and our desires has been a success for all.

In the era of climate change and more frequent, larger wildfires, beavers are more important than ever-beaver riparian areas are less likely to burn, and if they do, they suffer less damage; beaver ponds improve water quality after wildfires by capturing more fine sediments, benefitting fish and insects; and active beaver dams not only trap organic content, they also keep organic carbon sequestered in the surrounding landscape by elevating the water table. If not captured and contained, organic carbon oxidizes and is released into the atmosphere as greenhouse gas, further contributing to climate change. Studies done at Methow Beaver Project beaver ponds by Dr. Peter Wimberger and his students have demonstrated that these benefits occur within just a few seasons, not waiting decades.

Wimberger says: ‘The shift to seeing beavers as integral ecosystem engineers parallels the shift in how western science views the human/nature relationship. The rise of ecology, animal behavior, conservation biology, climate science and restoration have changed the way scientists look at organisms and forced us to acknowledge the inescapable reciprocal impacts of humans on ecosystems and organisms on each other, including us. Western sciences are slowly learning what many Indigenous Peoples have known for millennia.’

Working with beavers to help restore whole ecosystems is a clear and present solution for a clear and present danger. Once, beavers were here in vast numbers, creating a lush continent rich with flora, fauna, and fresh water; and they can be here again, living and working among us, our neighbors.

Let us say to the beavers: we belong together on this land we call home.

IV. EPILOGUE: A THREAD TO FOLLOW

FOR MY WORK, I often research for months before making anything. By contrast, gardening had been a whimsical outlet, with water conservation as a loosely defined goal. That vision has been drastically widened in these past two and half years, and I am re-evaluating my work as a gardener and as an artist, and wondering if those are necessarily separate things?

TWIG RINGS: I built several twig rings around the yard, hoping to slow down the neighbors’ cats when they stalked the birds. The purpose was to slow them down so the birds might have a chance to get away. I suppose they worked in some way, I often found cats sitting in the middle of these rings, quite relaxed, much like you see cats sitting whenever they find boxes. Over the years, coyote population has exploded in our neighborhood, and it’s now rare to see outdoor cats, and the twig rings are long gone.

Revamping a mature garden with different goals in mind has been challenging, not just because there is so much to learn but also I am emotionally attached to many plants that I raised from 4′ or 6′ pots that are now mature trees or shrubs. Looking through garden photos from the past 30 years, I’m remembering the ephemeral objects I built—the twig rings to thwart the neighbors’ cats that killed birds, or the bird entertainment center constructed from sunflowers—and remind myself that gardens have always been impermanent, and therefore renewable, an echo of their wild past.

Keeping in mind that with impermanence comes renewal has been helpful in resolving my attachments. My garden installation ‘To Thwart Domestic Cats in Favor of Wild Birds’ has re-emerged as a thread to follow-after decades of making work as an observer of the natural world, I now ponder making work as a participant.

TWIG RING

My garden rat’s work on the irrigation system set me on a path towards restoration and reevaluation-to be more collaborative and empathetic with the wild, both as human and as artist. Beavers, unlike my rat, do the actual work of environmental restoration-creating ponds, wetlands, aquifers, firebreaks, and carbon sinks-directly and indirectly benefiting life on earth. If we humans can also be good denizens of the planet, understanding that our futures are intertwined, we can achieve our common goals. These restoration projects involve extensive human participation, but our cohabitants are showing us the way, if we are willing to pay attention and learn from them.

NEST: I have had a giant tumbleweed hanging by my front door for many years and this is the second pair of birds that have decided to make a home there. The parent house finches raised 3 babies. The nest is beautifully speckled with the work of the baby birds, not old enough to leave their home to do their business but managed to create a beautiful pattern. These white speckles (fecal sacs) are good indications that the nest was a successful one. (Photo was taken through a window.)

V. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

WITH GREAT APPRECIATION for biologist Peter Wimberger, his fellow researchers, and his students for their work and publications on the Methow River watershed; Ben Goldfarb, author of Eager; Robin Wall Kimmerer, biologist and author of Braiding Sweetgrass; Doug Tallamy, entomologist and author of Nature’s Best Hope and The Living Landscape; the publications and lectures of so many scientists and my 2022 Oregon State Master Gardener instructors. Together, they have helped me gain a greater understanding of our interconnected world. Also with thanks to my neighbors who shared their family stories and photographs, and all the people at universities, state agencies, city agencies, and non-profits who have made their research and records available for the expansion of our knowledge.

ENDNOTE

Science Stories is an online exhibition promoting collaborations between artists and scientists, sponsored by the University of Puget Sound. Originally conceived and curated by Jane Carlin, Library Director of Collins Memorial Library at University of Puget Sound; Lucia Harrison, Faculty Emeritus of Evergreen State College; and Peter Wimberger, Professor of Biology and Director of the Slater Museum of Natural History at the University of Puget Sound. Peter Wimberger was also the collaborative scientist working with Shu-Ju Wang to develop Castor and Sapient.

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 13, THE ART OF EMPATHY

Published November 2022