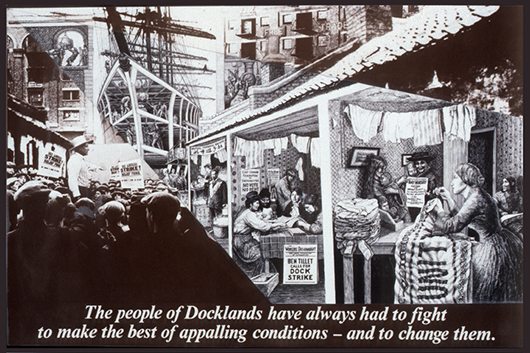

I. EAST LONDON – A HISTORY OF STRUGGLE

THE FLOW OF THE RIVER THAMES has been the lifeblood of London over many centuries. Since the first Bronze Age settlers, it has provided sustenance, transport, trade, work and pleasure for a population that now exceeds eight million. Communities grew up along the river to the east of the city to service its developing trade, but while this area was a hub of wealth generation, it has also seen the city’s greatest poverty. A focus point for new immigrants, it became home to a range of different cultural groupings, from the Huguenots in the seventeenth century onwards. Many entered with the trade ships, gravitating toward the work opportunities and cheaper living of this industrial quarter or aiming to join others from their own cultural backgrounds. Despite the poverty, however, it would be a mistake to see East Londoners as victims. Necessity drove these communities to become highly organized, and it is their determination and resilience that has led to this current urban territory of astonishing energy, diversity, and culture.

I first came to East London in the late 1970s and was overwhelmed by the intensity of its community life — a welcome contrast to the suburbs to the west and to my upbringing. I felt that I had come home, and this area has indeed remained the context of my personal and professional life for over 30 years. As an artist wishing to make a difference with my work, I discovered overlapping social, cultural and political networks that made it possible for me to engage with other initiatives and explore dimensions that art could bring to them. One such campaign was instigated in the early 1980s in response to the Thatcher government’s wide-reaching redevelopment plans for the London Docklands. With the introduction of containerization of cargo, many incoming ships had begun to dock further downriver, leaving stretches of derelict land bordered by corrugated iron, and warehouses that were now occupied by small businesses, workshops, and artists’ studios. A significant area of land was involved, extending for 8 miles on both sides of the river eastwards from Tower Bridge, as well as several miles inland. However, it was far from empty. Its inhabitants remained, but were crowded into estates of high-rise flats or streets of run-down terrace houses. Unemployment was high, and services poor. Development was in fact not a contentious issue — the only question was in whose interests these new improvements would be made.

HOUSING 3, 1985-7, 18′ x 12′ (5.49m x 3.66m) photo-mural. © Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, Docklands Community Poster Project. Third image from the second sequence of photo-murals dealing with issues behind lack of adequate housing for local people.

II. THE DOCKLANDS COMMUNITY POSTER PROJECT

YEARS OF CONSULTATION identifying the homes, jobs, and services still so desperately needed in the area were thrown out by the incoming Conservative government of 1979, which regarded the area simply as the biggest piece of real estate in Europe. A new act of parliament enabled the instigation of a new corporation with powers to ‘vest’ the land from locally elected borough councils and sell it to developers. Around this point the Trades Councils of the area approached me, together with my artist collaborator and ex-partner Peter Dunn, to create a poster that would spread information warning people of what was about to take place. This followed several years during which the two of us had worked on campaigns with local trades unions, creating posters, video, and exhibitions about cuts in health services. The value of the longevity of artistic/community relationships cannot be underestimated. It was through this previous work as committed cultural activists that we had gained the trust of these groups. The high level of organization in the riverside communities meant that we were able to consult with groups already federated into associations representing each dockland area. Through these meetings we encountered a range of needs. Posters were indeed wanted — but ‘large ones’ — along with a photographic record of events from the community’s perspective, visual dissemination of the issues concerned within and beyond the riverside neighborhoods, plus help with graphics for the various campaigns underway. There was no funding at this stage; however, we approached one of the borough councils for materials and received a short part-time residency from the regional arts association. Nevertheless, the work could not have been achieved without the support of the Greater London Council (GLC), London’s local elected authority. The GLC had not only just turned Labour, but had installed a new leadership that was, unusually, to the left of that party. During their time in office this administration transformed the city both culturally and in terms of its infrastructural development. Their support of both the dockland communities and arts practice that engaged directly with people enabled the ideas generated by our local consultation to develop into a significant programme of work.

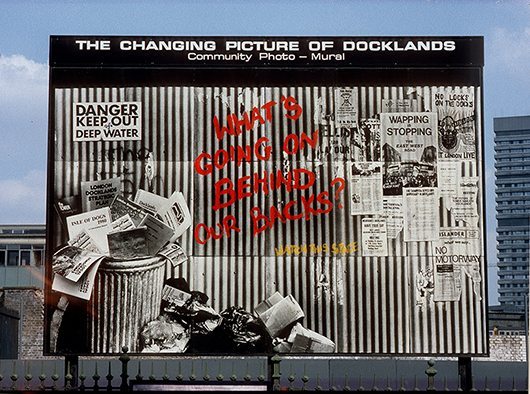

WHAT’S GOING ON, 1982, 18′ x 12′ (5.49m x 3.66m) photo-mural. © Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson, Docklands Community Poster Project. First image of the first sequence of photo-murals exploring issues surrounding the re-development of the London Docklands from the viewpoint of local communities.

A central part of the Docklands Community Poster Project‘s production was a series of large-scale photo murals that toured around eight specially constructed billboard sites, visually setting out the arguments and concerns of the communities regarding the redevelopment. Six people were eventually employed within the project for administration and installation of the photo murals, and to assist with the production of graphic work, exhibitions and events. Peter and I undertook the coordination role, created the photo murals, and built a photographic archive that recorded both the campaigning and sites of development1. A committee of local residents and activists oversaw the organization’s programme while providing information, support, and a collaborative context that made such interventions possible. Thus, an arts project that began as a request for a poster became the cultural arm of an extraordinary campaigning community over a period of 10 years.

Over a thousand people from the London Docklands sailed up river to protest against the way the area was being re-developed and to deliver the People’s Charter for Docklands to Members of Parliament. The Docklands Community Poster Project worked in tandem with the Joint Docklands Action Group to create banners and ephemera and enable the campaign to serve both as political rally and celebratory festival.

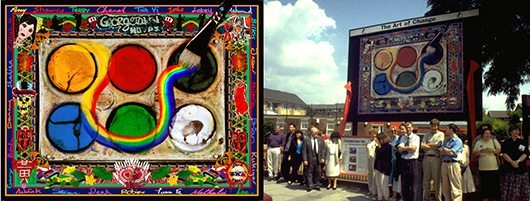

III. THE ART OF CHANGE

SO SUCCESSFUL WERE the policies of the GLC and the activities it supported that the right-wing Tory government was desperate to be rid of them. It had tried unsuccessfully to discredit the GLC’s leader and policies, but in the end only accomplished their removal through the extreme measure of abolishing each of the UK’s Metropolitan Authorities. With its main source of funding removed, our organization addressed the change in circumstances by turning to some of the other issues that had arisen as a result of the shifts in East London’s urban environment. The organization was transformed into The Art of Change and, over a further decade, created community-driven artworks and cultural initiatives in and for the public domain, raising funding on a project-by-project basis. My own growing family led to my interest in work with young people, and I embarked on the first of many projects that over the years involved participants ranging from infants to university students. Engagement with activists had offered a surprisingly good grounding for this and led to my recognition of how the best participatory work is often also collaborative, with each party contributing expertise towards an outcome that none could achieve on their own. As with the docklands communities, I concentrated on bringing the largely ignored voices of young people into the larger social sphere, enabling knowledge gained through their direct experience to enter the realm of public discourse.

CELEBRATING THE DIFFERENCE, 1994. Digital montage displayed as a 16′ x 12′ photomural produced with pupils from the Isle of Dogs, East London. Working with a group of culturally mixed teenagers, the project dealt with issues of culture and identity, commonality and difference in an inner city area fraught with racial tension.

Lessons of organizational process learned from the docklands experience also informed the projects of my new organization, and I discovered that these could have an artistic as well as a facilitating function. In my early work in schools I created frameworks that were both visual devices and a means of enabling group participants to make their own personal contributions to a collective project. Following the enormous technological developments of the 1990s, our earlier black-and-white photomontage work became transformed through digital imaging, while the burgeoning Internet brought new possibilities for multiple engagement and a platform for collective creativity.

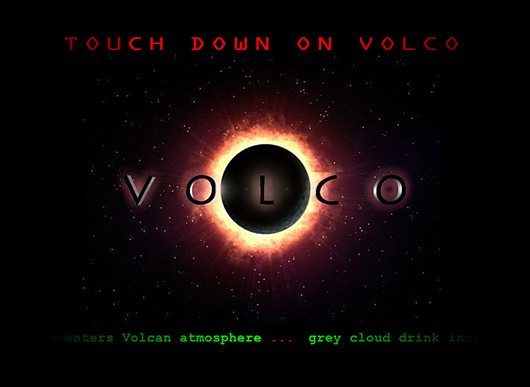

VOLCO. 1999-09. An evolving planet in cyberspace constructed by young people aged 7-13 interacting online with others of different cultures and life experiences towards the creation of a society built on co-operation and through collective imagination. Over 1000 children contributed to this increasingly complex virtual society over a period of 10 years.

IV. cSPACE

BY THE NEW MILLENNIUM, undermined by further cuts in public funding, The Art of Change could not keep going, and Peter and I also went our separate ways. My strategy for survival was to found a new organization at a university. Although my new host offered no financial support, the higher education environment afforded a certain amount of material protection and also opportunities for interdisciplinary working. Furthermore, the new campus of the University of East London was perched right at the edge of the Royal Docks, the most easterly outpost of what had now been named the London Docklands. It was here that I established cSPACE as a charity to provide an organizational base from which to continue ongoing projects, as well as raise funds for new ones. The first of these was VOLCO, a planet in cyberspace created by over a thousand children in four countries, a project that modeled for the next generation a new world of their own making based on principles of dialogue and cooperation. Subsequent projects included Precious Places, a response to a request by residents of North Woolwich and Silvertown for a project that would help unite longstanding with incoming communities in this narrow stretch of land between the docks and river, still hardly touched by development.

THE YOUNG PERSON’S GUIDE TO THE ROYAL DOCKS, 2005-07. Online guide developed with young people to address issues of heritage and regeneration in London Thames Gateway. Site investigation, interviews, photographic documentation, sound recording and archival research supported a methodology both educational and collaborative, while also involving mentoring across three levels of education. Photo shows web site launch at the Museum of London Docklands, March 2007.

My work with young people continued with a Young Person’s Guide to the Royal Docks, an online guide demonstrating what local youth felt to be best about their neighborhoods, and at the same time established their stake in the future of this area. A similar guide followed, created in the face of the impending London 2012 Olympics, this time covering the whole of East London. Over a period of 5 years 400 teenagers on each side of the river documented their neighbourhoods and posed a viable alternative to the gloss of the Olympic juggernaut with its much-publicized youth focus. The online guide and free newspaper produced by these young people were practical resources for the real world, and laid foundations for a global youth network — a new project currently under development.

Despite their roots in the more direct cultural activism of earlier times, these projects also epitomize a shift in strategy that responded to changes in the spheres of both art and politics during the intervening decades. In the UK no longer was there a broad belief in a more equitable society to be achieved through collective action. During the right-wing backlash of the late 1980s and 1990s that followed the Thatcher regime, individualism had come to the fore, while activists and the young now fought on single-issue campaigns or expended frustration in riots. Instead, these projects drew on another lesson from the earlier years — the power of alternatives. The docklands communities had experienced the relative weakness of oppositional practice that ultimately reinforces the power of the status quo, and adopted other strategies to address the needs of local inhabitants. The Peoples Plan for the Royal Docks was one such initiative. A well-researched set of proposals, backed by the GLC’s Popular Planning Unit, had driven the government’s plans for an airport in the Royal Docks to formal public enquiry and won. Although the enquiry’s recommendations were ultimately ignored, The Peoples Plan remains to this day a model of community-based planning. It also informed the projects I later developed with young people, with The Young Person’s Guide to East London creating a voice of local youth that pre-empted the populist claims of the Olympic initiatives.

THE YOUNG PERSON’S GUIDE TO EAST LONDON, 2008-12. Four hundred teenagers across East London contributed photographs, video and their own recommendations to produce this online guide, creating a unique insight into the area from a young person’s perspective.

V. ACTIVE ENERGY

A RESEARCH PROJECT by Queen Mary University of London2 concluded in 2007 by inviting artists to explore why the life experience of older people was failing to inform developments in new technology. As a result I found myself visiting the Geezers Club, a self-run group of working class older men at an Age UK center in Bow, East London.

Members of the Geezers Club on a trip to Three Mills in Bow, East London in 2008 to investigate how water wheels had been used historically to harness the power of the River Thames.

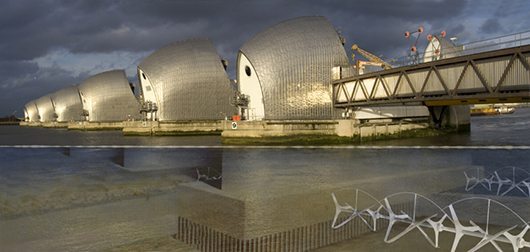

‘When electricity prices prevent older people from heating their homes, and the River Thames is just down the road, why aren’t we using it to power our city?’ asked one of the group’s members. My question to the group had been to enquire what technological developments each felt might best assist them or their communities in the future. I had thought they might come up with ideas for domestic gadgets, but that only demonstrated my own naivety. By the end of the first session the whole group of 16 or more senior men wanted to focus on the crucial issue of tidal power.3 While I had no previous knowledge of the subject, I nevertheless resolved to take them every step of the way that I was able. We had little time before the exhibition at SPACE gallery six weeks later. A historical water wheel was located nearby however and from here, with advice from the Sustainability Research Institute at University of East London, we researched turbines suitable for underwater use. At the London Flood Barrier we found an ideal barrage on which tidal turbines could potentially be mounted, since only the central lanes of this gigantic structure were used for shipping.

Visualisation of how tidal turbines could function on the Thames Barrier, exhibited at the Not Quite Yet, SPACE Gallery, London, February 2008.

Members of the group had by this time become so eloquent in their advocacy of sustainable sources of power, that video interviews I recorded to capture their views made a compelling argument. Large-scale projections of these in the gallery lent a voice of authority to an age group whose voice is rarely heard, and laid out the case for renewable energy in an accessible and engaging way. The exhibit had an enormous impact with the local press, and although the commission was at an end, we all felt that it could not stop there. Few of the Geezers had previous computer experience and I was able to raise a small amount of money to equip them with a laptop and peripherals to continue their research. Drawing on previous construction and mechanical experience, members of the group spontaneously started to come up with their own turbine designs to improve on those we had seen. Meanwhile engineers from University of East London joined our endeavor, donating their time out of interest in the project, and opening up access to a prototyping laboratory and testing equipment. The project became known as Active Energy.

Seeing that the group was still going strong, SPACE Studios became involved once more, raising funds for some intergenerational work. A team that included the engineers, the Geezers and I then ran a series of renewable energy workshops at a local boys’ school. Through this process a temporary small-scale wind turbine was created and installed on the roof of the AgeUK center. At night the energy it generated spelled out in lights the word ‘Geezerpower.’

Professor Ann Light, the social scientist who had undertaken the original research leading to the commission, was also attracted back into the growing vortex of energy and interest that the project was generating. The group now constituted an extraordinary informal transdisciplinary team, and she found us opportunities for collaborative public presentations and input into further university research.

Work on the project continues. Designs have been tested in the university’s flume tank, and a full-sized version tested and celebrated on a Thames barge moored opposite the Houses of Parliament. We cannot make those in control of our energy sources install tidal turbines on the Thames, but we can bring public attention to the issue in the way that art does so well. We can invite politicians and energy advisers and make our findings and designs accessible in the public domain so that others can take up where we leave off. We are not finished yet, however, so watch this space4

VI. AFTERWORD: LAMBETH FLOATING MARSH

IN MY ARTISTIC PRACTICE projects seem to evolve one from the other. As a result of Active Energy, a collaboration has already emerged with the owner of the barge where the turbine is being tested — a scientist with particular interest in the biodiversity of the river. In central London, as in most large cities, the banks of its arterial river have been shored up both to limit its spread and to maximize flow for river traffic. In the process however, habitats disappear that would otherwise support the river’s micro-organisms on which larger creatures depend. The barge is moored on the site of the historic and extensive Lambeth Marsh, of which no vestiges remain. Our new proposal is for a prototype floating reed bed secured along its length. Centrally located will be a giant Petri dish functioning as an artificial rock pool, where river organisms are able to accumulate with the ebb and flow of the tide. A microscope will enable essential monitoring to take place, for which we aim to enlist the help of local school children, while nighttime projections onto the sidewalk will bring the issues to public attention.

Why should an artist involve herself in the domain of communities, activists and other disciplines? Those involved in this field of practice will not be unfamiliar with the accusatory labels of glorified social work, education, or indeed, complete puzzlement on behalf of the art world. During the Active Energy project members of its informal transdisciplinary team became interested in understanding our individual interests in this joint work since there was a purpose and energy that drove each of us from our particular perspective, but often toward different goals. This resonated with much of my previous experience, where participants or collaborative partners bring their own needs and desires to a project that then become resolved through a shared outcome, though often in different ways. In Active Energy the engineer expressed his interest in the development of technological solutions to a problem and its open source dissemination. The social scientist views the work through a lens of citizen-led innovation, while the Geezers want to use their life experiences to leave a legacy of potential benefit to their community. From my perspective, I regard the purpose of art as nothing other than the creation of meaning. Active Energy would not have happened, or progressed, if it had not been an art project. Imagine a range of different ideas and knowledge thrown into a pot. It is the artist’s role to hold that receptacle while it heaves and rocks with the ‘terrible’ coming together of those disparate elements as they reconfigure themselves — and something new emerges. This is, of course, the creative process, and something at which artists are particularly adept. I set out wanting to use my art to make a difference, and discovered that the most important factor in achieving this has been to work with the creativity of others.

END NOTES

1 This photographic archive is now held at the Museum of London Docklands as their only photographic record of this period documenting the redevelopment from a community perspective.

2 The Democratising Technology research project was led by Professor Ann Light, who later became part of the Active Energy team. See http://www.demtech.qmul.ac.uk.

3 Members of the Geezers Club had recollected how developments in tidal power were very much in the news during the 1980s. Support for research into renewable energy was in fact halted by the Thatcher government and was only reinstated when Labour came back into power over a decade later. However this time it was wind power that received the subsidies, while research into the creation of renewal energy from UK water resources continued to lag behind. The current Conservative/Liberal coalition prefers to develop the nuclear industry.

4 See www.active-energy-london.org.