Location: Glasgow, Scotland

My artistic subject matter is the life of nature.

By contemplating nature, I seek to renew my own identity.

-Reiko Goto Collins

Plein Air. Turchin Center for the Visual Arts, Appalachian State University, Boone, NC, 2019.

PROLOGUE

LISTENING TO MORE than human others has an aesthetic quality that appeals to our ethical sensibilities and care towards others. I had written previously, ‘when we think about the public realm, often we think about ourselves, and forget other beings. We forget that every public place also consists of silent beings such as plants, insects, wildlife, soil, and air’ (Goto, 2012) [1]. I think of three stories [2], and images that demonstrate what it means to listen to other beings. The first story reveals an image, a person and birds are facing each other. Their gestures suggest the person is talking to the birds, and the birds seem to be paying attention and listening. Second, there is a wise man, who has a magic ring that makes him special, able to understand what animals are talking about. The third story reveals another image, a person encounters a family of starving tigers. He takes his clothes off and jumps off the cliff. Underneath the cliff, the mother tiger and her cubs express their gratitude toward the person’s compassion and his sacrifice.

How do humans understand what other beings are saying? How does art and spirituality relate to this understanding? I reference two spiritual practices familiar in Japan: Buddhism and Shinto. Through imagination, a blank piece of paper can represent Buddhism’s inter-connectiveness. When I look at a blank piece of paper [3], I can imagine the sunshine, clouds, rain, and forest. In contrast, the spiritual awareness of Shinto originates from animism whereupon a sacred place sometimes has no shrine, just a rock, water, or a tree. The spiritual relationship consists of a person, natural elements, and the environment.

More recently, I rely on Edith Stein’s philosophical idea of empathy defined by the human ability to understand the other person. Empathy reaches beyond self-interest; this is how it differs from sympathy. Sympathy is an act of assuming feeling in another based on what we know. In this sense it is founded on an intellectual understanding in which we rationalise a situation and impose a projection. Unlike empathy, sympathy reflects one’s own experience and intellectual understanding rather than reaching beyond it. Empathic experience involves an intellectual understanding expressed as a new idea. Sympathy is based on one’s self-interest in this context. Empathy is not based on one’s self-interest. It is a reaching beyond self but without losing or forgetting oneself. We bridge the gap between self and other. We resonate with the feeling of the other and amplify it. Empathy in this sense occurs between subjects. It is inter-subjective. In this way empathy helps us to enrich our own world-image through different individuals.

In this article, I endeavor to capture empathic moments with living things: butterflies, rats, a pigeon, trees, and a horse. The accompanying images of my artworks are related to my empathic experiences, they are stories constructed through memories that consist of colours, touch, smell, and sound rather than words. The story of the butterfly is a true story from my childhood, while Nezumi and If I were a pigeon (1987-1993) are based on my volunteer experiences at the California Wildlife Center [4]. The fourth story Breath of the tree is about realizing that science and technology can contribute to empathic experience. Plein Air (2012- present), based on our experience in North Carolina, I developed the sound sculpture, Plein Air, during the period between 2007 and 2011 when I was completing my PhD [5] at Robert Gordon University in Aberdeen Scotland. The last story is my latest work with a horse, begun in 2018. Horses are larger and stronger than people. Listening when he says ‘no’ has become an important practice in building a relationship.

I. BUTTERFLY

ONCE A MISCHIEVOUS BOY tortured a butterfly in front of a little girl. As he tore the butterfly’s wings, the little girl cried and begged him to stop. But he did not stop, and the butterfly died. After the boy left, there was nothing for the little girl to do except tearfully gather the broken wings and body parts. She buried them with flowers.

Many years later, the child was no longer a little girl. But she never forgot about the incident. There were so many mischievous boys and girls she had encountered throughout her life, the influence of the memory of the butterfly made her isolated from other people. Early one morning, while working as a member of a maintenance crew in an art school, she found a new-born butterfly on the structure of a garbage compacting machine when she was emptying the trash. The butterfly was bathing in the morning sun, preparing to try out its new wings. It looked very soft and fragile. She was concerned that the butterfly might be caught up by the machine. She said to the butterfly, ‘Please don’t be afraid of me. I just want to move you to a safe place.’ Then, she slowly stretched her hand out to the butterfly. At first the butterfly did not move, then, started climbing onto her hand. She carried the butterfly to a garden. The grass was shining with the morning dew. She tried to place the butterfly down on a dry tree bark. The butterfly slowly moved to the safe spot. The promise made between the little girl and the butterfly was together fulfilled at that moment, and the garden became a holy ground.

In 1991 I was developing the idea of ‘a butterfly garden’ for the roof top of the Moscone Center in San Francisco. I met with Barbara Deutsch who since 1984 was creating a butterfly garden on Potrero Hill. She showed me various plants that butterflies rely on to lay their eggs and feed their larvae. After the meeting, I could recognize those same plants around our studio [6] and found caterpillars and eggs on them. Butterflies were always near me, but I just did not notice!

The Anise butterfly loves the wild anise which grows wild and is considered a weed that was introduced to California. When disturbed, the larva of this butterfly emits a strong smell of anise, which meant that I could slowly walk through a field and smell their presence before I even saw them. Tim never could smell them and would laugh whenever I’d say ‘they are here’. I started rearing and releasing butterflies, learning as much as I could by tending to their life cycle. A natural and almost poetic exchange between the creatures, their larvae plants, and the places they chose for habitat.

Haru / Spring, Installation, 1989. 30 chrysalides of Anise swallowtail butterfly attached on dry fennel. The adult butterflies emerged in the installation, then flew out from the window. The Headlands Center for the Arts, Sausalito, California. Photo Credit: Richard Barnes.

ChÅen / Butterfly Garden, Public Artwork, 1993. Collaborators: Barbara Deutsch, Donald Mahoney, and Leslie Soul. The team developed an experimental butterfly habitat, at Yerba Buena Gardens, the roof of the Moscone Center in San Francisco. Photo Credit: Reiko Goto Collins.

II. NEZUMI

NEZUMI MEANS RAT or mouse in Japanese. It was the title of an installation I presented for an annual exhibition at the Walter/McBean Gallery, San Francisco Art Institute in 1989. I was showing in this group exhibition with artists Mildred Howard, Hilda Shum, and Guadalupe Garcia.

Just before finishing my master’s degree in art, I started working at the Wildlife Center in San Rafael California as a volunteer once a week. The place provided care for injured or baby wildlife such as squirrels, opossums, raccoons, pelicans, cormorants, seagulls, jays, hawks, owls, sparrows, swallows, warblers, hummingbirds, and pigeons. There were also laboratory rats that were kept as a food source for hawks, foxes, and other carnivores. There were about fifteen cages and each cage held two to four male and female rats. They made many babies. My job was to clean their metal cages by changing the wood shavings and providing them with water and food. Sometimes I gave pellets one by one to the rat, who gently received each pellet with their mouth and hands. Pink and soft, their hands look like human hands. I could hear the licking sound when a rat was drinking water from the metal tube of the plastic water bottle.

The rats were constantly chewing things that would limit the length of their teeth. I was more surprised to see the different marks of the chew patterns on the towels lining each cage. One towel was very finely chewed. It seemed to be used to provide protection and warmth for the baby rats. Another one was completely torn to shreds. The towels made me wonder and imagine what the rats were doing in the constrained environment. What would make each towel different?

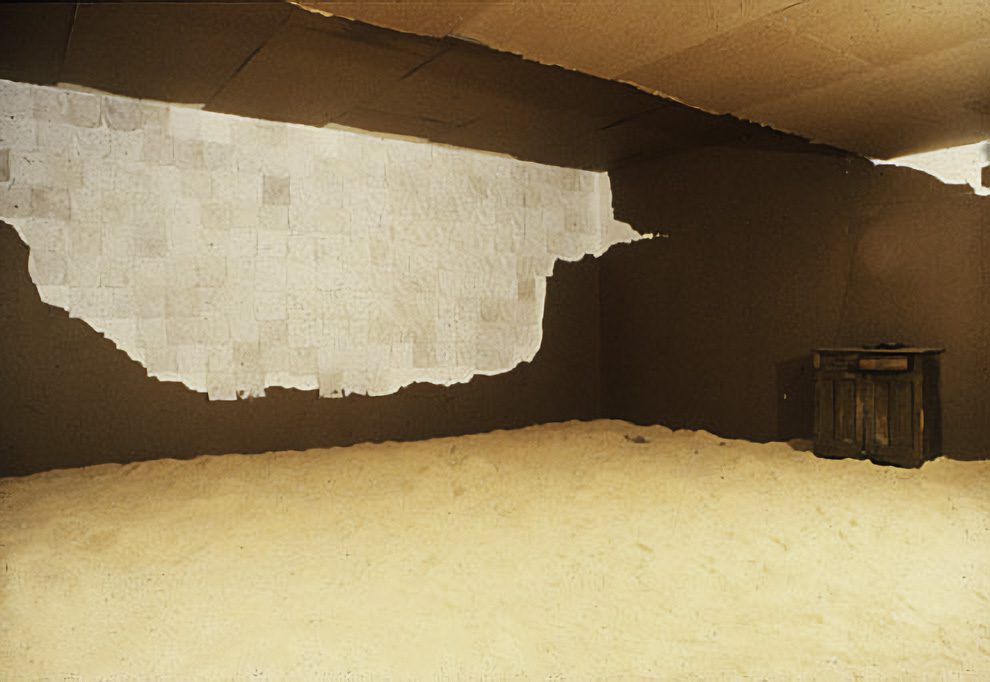

I decided to present these towels created by the Nezumi when I was commissioned to make an artwork for the Walter/McBean Gallery’s annual exhibition. Every week I placed new white face towels in each cage. I provided the rats 200 towels over the course of three months. My idea was to transform the gallery space to become a human-scale rat box (11.5 feet x 28.5 feet x 10 feet tall). Would this space make the audience feel as if he/she were a rat? I covered the walls, windows, ceiling, and entrance with cardboard. People had to go through a large hole in the cardboard to enter the installation. The lighting of the space was kept dim. The natural light came through the holes on the cardboard and traveled across the gallery space. The floor was covered with a massive amount of wood shavings. The two hundred towels were washed and hung on one of the walls. Some of them moved slightly with the air circulation from the window. A tape recorder played a short segment of an audio of a rat licking and drinking the water from the dispenser. Bruce Brody, an artist friend, let me use an old chest of drawers that had been scratched and chewed by rats for years. On top of the chest, I offered water and dry food in metal dishes.

The day after the opening, I went to the Wildlife Center and cleaned the rat cages meticulously. I brought some leftover food from the opening for the rats. They seemed to be excited. I could feel their hands were touching my hands. After I closed the metal doors, I could hear sounds of their nibbling the food and licking the water bottles. All the cages were vibrating slightly.

After the exhibition, I decided to live with four rats. I presented a performance with two of them, Stewart ♂ and Pistachio ♀, at the Headland Center for the Arts in Sausalito, California. I also adopted two sisters Emily and Charlotte from the Wildlife Center. Sometimes I let them to wander around out in our studio. Whenever I asked Charlotte to find Emily, she brought Emily back. All my rats lived for 3 years. Three of them had tumours when they died.

Nezumi, Installation, 1989. Presented for San Francisco Art Institute Annual Exhibition. Photo Credit: Michael Selic.

Nezumi. Two hundred pieces of towels (details), each 12’x12′. Photo Credit: Reiko Goto Collins.

![]()

III. IF I WERE A PIGEON

I HAD A PIGEON named Oedipus. He was a male rock dove. He came to the Wildlife Center as an orphan.

Every summer the center was filled with baby birds. Volunteers were busy cleaning the baskets that held the chicks and feeding them every three hours. There were some special volunteers who handled baby hummingbirds that had to be fed every half hour. People admired how the specialists successfully brought a weaned hummingbird back to the center.

During the summer baby pigeons were sometimes neglected. Cindy, one of the volunteer coordinators, said if pigeons looked more special, this would not happen. The center had limits on how many baby birds could be taken care of. The Marin (county) Wildlife Center worked under San Francisco Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA). Over two busy summers (1990-91), the SPCA refused to accept pigeons brought in from the public. Once, I brought one hundred baby pigeons into our studio. They needed a few more weeks to mature before they could be released. We let them out in the studio while I cleaned their cages. After eating food and stretching their wings, I could put them back into their cages easily. They were well mannered. Tim was helping to teach them how to fly in the studio.

Oedipus was one of the baby pigeons. He became fully grown, but the center could not release him because he was pecking and biting people’s hands and spinning around endlessly in the cage. Some people thought he might have a balance problem. The center asked me to take him, if I was interested. Otherwise, he was going to be euthanized.

When I brought him home, Tim asked whether he could fly or not. I said the center never let him fly, but his wings were in perfect shape. Tim asked me to toss him into the air in the studio. The bird flew but hit himself on the wall and fell. We caught him before he could hurt himself. Tim suggested the bird had a bad eyesight. When we used a flashlight to shine into his eyes, there was no reaction. When we put a candle close to his eyes, no blinking. The pigeon was born blind although his eyes looked normal. I named him Oedipus [7] and called him Oedi.

If I Were a Pigeon Computer graphic (38’x23′) combining a pigeon and the artist’s faces, 1992. Photo Credit: Tim Collins.

The pigeon did not settle down at our studio. I could not handle him. Sometimes he was standing in his filthy water pan for hours. The tips of his tail feathers were now smashed. When I talked about this miserable situation to Al Wong, an artist friend, he introduced us to his friend who was very good at birds. She came to our studio and looked at the pigeon. She told us she had experience taking care of parrots. Pigeons were perhaps a lot like parrots?! Tim and I explained why we got him and how he was doing. I handed Oedi to her. He bit her hands, but she was not upset and started giving him a neck massage with her thumbs. Soon he stopped biting and became calm. After her visit, Oedi stopped pecking and biting us. He seemed to understand our hands differently. When we called him, he called back and made his circular movement. The movement was no longer intense. I gave him a large cage but not too tall. He could stretch and flap his wings. I placed a large shallow ceramic water dish in his cage. He took a bath frequently and perched on the rim of the dish to groom his feathers. I placed a folded white bath towel in the cage. He took a nap wrapped inside of the towel. He loved getting a neck massage. He sat on my lap and closed his eye lids. Sometimes he groomed my hands. His feathers were always clean and felt like velvet, those on his chest were vivid iridescent colours.

If I Were a Pigeon A performance with a blind pigeon at Intersection for the Arts, San Francisco, California, 1992. The movement of the pigeon created a shadow play and sound through the mechanical system. Computer programming: Richard Reed, Engineering: David Nelson. Photo Credit: Tim Collins.

IV. BREATH OF THE TREE

IN 2000, MY PARTNER Tim Collins and I visited the Duke University Forest, ecological research area in North Carolina. The scientists were wiring sensors to the forest to measure the reaction of the trees to future levels of carbon dioxide. A scientist invited us to climb a forty-foot-high structure that was built among pine trees. He showed us portable equipment that would measure the amount of photosynthesis from the tree leaves. He grabbed a branch of the pine tree and placed the needles into a leaf chamber that was connected to a measuring device. When the sun emerged from a cloud, the photosynthesis rate went up. The scientist asked me to put my hand on the leaves to block the sunlight. The meter went down immediately. We were astonished to see this quick response from the tree.

By 2007, it was clear to me that I wanted to explore an empathic relationship with trees. Duke University Forest was my model. First, I wanted to collect specific data in regards to the ‘sound’ emitted from trees and test this data to make sure it was scientifically accurate. Then we needed to try to ‘hear’ the data using sound programmes. In 2008 we continued this project when we went to a residency at the Headland’s Center for the Arts. We gathered data from native trees, saved it to a hard drive, and then used a sonification programme to hear the changes. For example, an oak in the very hot afternoon produces a deep base sound, almost like the tree was asleep. When we got back to the Robert Gordon University in the UK, a plant physiologist checked our data printouts and commented on our sampling protocol. He listened to some of the sounds as well, and he laughed when he heard the oak. He explained that it was so hot the tree had shut its stomatal openings so that it would not lose any moisture; it had gone into a resting mode and therefore produced very little data. We could hear the life of a tree for the first time.

Chris Malcolm is a collaborator with computer skills. He understood why we wanted to let the tree control the sound composition. He built a series of programmes like jazz riffs that let us hear the tree and its physiological changes, first logarithms for photosynthesis and then transpiration. Then some base notes and chords for carbon dioxide and humidity, another for sunlight. Slowly we started seeing and hearing the tree react to environmental changes that we could notice in our studio. The common ground between the tree and myself was the atmospheric exchange, the comfort, discomfort and even distress that each of us ‘felt’ as the conditions changed. Listening for days and weeks at a time I would learn to care about trees differently.

Trees are not slow seasonal beings, but reactive, breathing, living beings who register changes to the atmosphere faster than we do. The exchange of the signs of life had empathic potential. I was experiencing what it meant to be alive with a tree.

Plein Air. Exhibition at Turchin Center for the Visual Arts, Appalachian State University, Boone, NC, 2019. Photo Credit: Reiko Goto Collins.

V. A BLACK HORSE IN A FIELD ON A DARK NIGHT

DARKNESS IS AN Irish Cob horse, heavily built yet not very tall, his coat is primarily black hair with long mane. He has been adopted as a member of our family in September 2014.

Glasgow is affected by its west coast location, weather blows in from the North Atlantic causing rapid changes that include the sudden onset of fog, rain, sleet, snow, and hail. As a result, conditions can be mild and nice one minute and breathtakingly cold the next. As the weather changes, Darkness’s woolly coat grows thick, but we still worry and we normally put a ‘rug’ (a waterproof jacket) on him if conditions are wet and cold.

It was on a cold December evening when we received a parcel delivery, a brand new rug for Darkness. Until then, he always wore second-hand rugs that had been ripped and mended. During dinner that evening, I began to worry about the bitterly cold night with the forecast of rain. Tim suggested the horse would be fine. A few hours later, now very late, I decided to step outside and I said to Tim when I returned, ‘we have to go out to his field and put the new rug on him.’ Tim got the car ready. As we drove, I began to worry about how we could find Darkness. I also worried about the other horses in the field, since it was very dark with no moon at all that night. As we got closer, we realized neither one of us had brought a flashlight, but we thought there was one in the car. We found the batteries were dead. Parked on the road along his field, I wanted to give up, as I didn’t know how I could find him. Tim just laughed and picked up the rug and said, ‘let’s have a go. If we find him, great, if not well, we will just have a wee adventure.’ He climbed over the gate, and I followed. We stayed close together as we could only see a few meters ahead as we walked into the dark field. I called ‘Darkness’, but there was no response, no sound at all. The field was huge, I was beginning to think this was a mistake.

We walked and walked and neither of us saw nor heard any horses. Then I felt something coming toward us. This approaching creature had a familiar presence that preceded his arrival. Slowly, through the dark night, a horse was emerging. We could hear it breathing, I whispered to Tim, ‘Darkness?’ The big fellow leaned closer and put his nose in my hand, knickered a bit, then greeted Tim. We patted him, laughing that this great hairy beast would bother to find us on a night like this. The rest of the herd came forward. We couldn’t quite see them, but we could hear that there were many horses around us. We got a bit nervous. Darkness stepped away and trotted toward the herd. We could hear him working in a circle. He was pushing them away from us! He came back through the dark misty night to us again, the surrounding area now very quiet. I asked him if I could put the rug on him. He was very calm and relaxed, curious about our presence. He stood still as I put the rug on his back and connected the clasp at his chest, then across his belly, then through his back legs. Once it was on, he shook his head a bit and headed off into the night. We walked back to the car laughing at the magic and wonder of the experience.

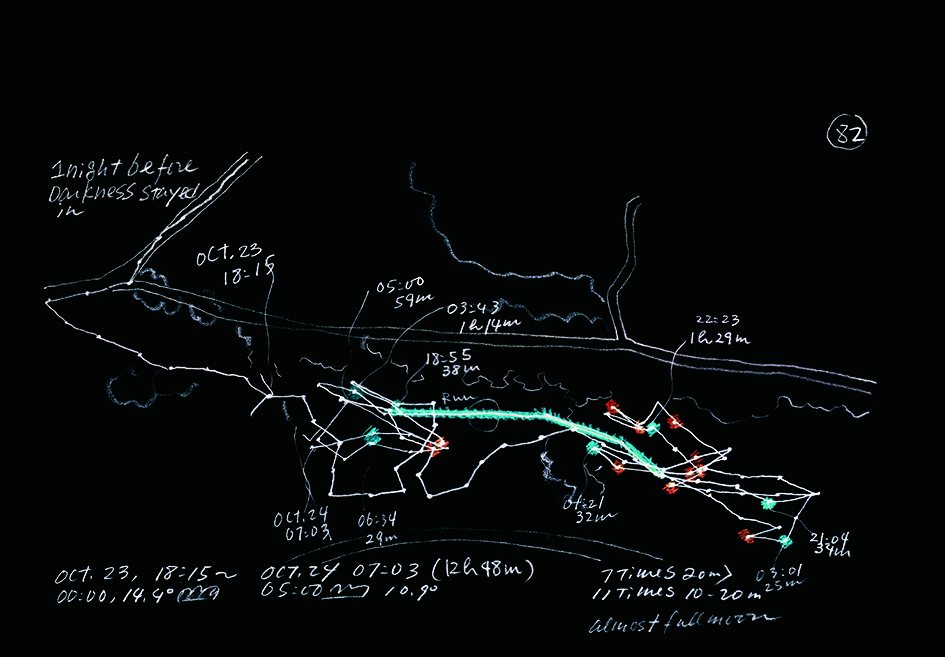

Lair, 2022. It consists of 120 drawings and some photographic images of the lair. Drawings were based on GPS data of a horse’s movements during nights between the summer solstice and winter solstice in 2018. Photo Credit: Reiko Goto Collins,

Lair, details, 4’x5′, 2022. Photo Credit: Reiko Goto Collins

Lair, details, 4’x5′, 2022. Photo Credit: Reiko Goto Collins

![]()

EPILOGUE

I PROVIDE THESE five stories about five different living things: a butterfly, Nezumi, a pigeon, trees, and a horse. What does each story mean? Each story comes from my own experience and memories. The empathic experience becomes a metaphor, an idea, a symbolic sign, or other meanings.

In the beginning of this article, I introduced three stories. The first one is about St. Francis. I think of Giotto’s 1299 painting of St. Francis Preaching to the Birds, showing the importance of communicating with other living things. The second is a biblical story about King Solomon. The ring is a metaphor that gives the wearer the power to listen and understand other living things. In the preface of his book, zoologist Konrad Lorenz had cited Rudyard Kipling [8] in a quote about Solomon. Lorenz’s scientific method is located and practiced in a shared environment with Jackdaws and geese rather than in a laboratory. And the third story is about an image [9] of Bodhisattva, a person who practices being a Buddha on earth. In the story of the tiger, this person sacrifices his body to save the starving tigers. The story symbolises the perfection of Buddha’s compassion that is very hard for ordinary people to imitate.

At the heart of empathic communication is the ability to understand the other and to be understood by the other. This kind of give and take relationship can create a positive energy feedback loop between the person and the living thing. Every living thing has a different lifespan. Butterflies live for a few weeks to a few months, Nezumi lived for three years, a pigeon can live ten to twelve years, a horse lives for twenty-five to thirty years, and a tree can live two to five hundred years. Each species goes through its lifecycle in different speed. The speed of Darkness’s lifespan is at least three times faster than my life speed, while a Caledonian pine is much slower than all of ours.

By comparison, the creative process for making an artwork can provide an artificial duration that can span a few weeks, three months, ten years, or longer. It depends on an exhibition, a project, or the artist’s interest. This kind of duration can set us free from the time differences between humans and other living things if you compare it with the limit of time for a game of play. This is similar to the duration for an artist to bring their idea to fruition. Both human empathy and the empathy of other living beings can help us to become aware of each other and notice the changes to our lives. Compared to the lifespan of the creative process, the original idea can be developed, the rules of the game can evolve, and communications can be tested and refined.

A butterfly dies and comes back as a new life. We can see many cycles. It is probably better we stay in one place to observe them since they come and go very quickly, unless you want to follow where they are going. Monarch butterflies fly long distances from California to Mexico every year. It takes three to five generations for them to travel south over winter, then travel back north. They are such amazing creatures that somehow have a roadmap to their home grounds over two thousand miles apart. You will notice that following Monarch butterflies means following its host plant milkweed.

Nezumi was an exhibition and the process also marked time; providing towels to institutionalized rats every week for three months. The chewed patterns of the towels could help us imagine small segments of their lives and their emotional patterns. Oedi was a blind pigeon. One incident made him understand human hands were not hostile. He accepted being held by us, and he lived with us willingly for rest of his life.

When Tim and I go to a familiar forest like Blackwood of Rannoch in Perthshire Scotland, we see granny pine trees that are over 250 years old. They are still growing every year, but we cannot see the changes. The life cycle of a tree is much slower than other living things. Through the Plein Air project, we can listen to the way that each tree leaf changes its physical state constantly according to atmospheric changes. The experience of Plein Air provides a sense of oneness within the shared atmosphere, the light, air, temperature, humidity, and CO2. The epiphany Tim and I experienced in the Duke University Forest is retrievable by emphasizing experiences and memories. Every exhibition gives us an opportunity to listen to different trees in different environments. There are some similarities and differences. Some trees responded more, while other trees were slower or faster.

I asked Tim what the story of ‘A Black Horse in a Field on a Dark Night’ meant to him. ‘We were looking for him in the pitch-dark field. And Darkness found us. He seemed to notice we were nervous about other horses’ intrusions. He chased them and protected us from other horses that were curious about the unexpected visitors.’ If I have not been with Darkness for twenty-four hours, I am curious to know what he is doing in the field. We can imagine him eating the grass, running, playing with other horses, rolling around and laying down. Tim and I decided to put a small GPS device on his summer rug during nights. He seems to rest sometimes, but majority of time he is moving in the field. My recent work Lair tracks his movements with GPS during nights. Each drawing shows places where he stops and the duration between his movement from one spot to the next.

Before I finish this article, I would like to confess a few accidents that were caused by my naiveté and negligence. When I was working on the butterfly projects in San Francisco, I wanted to rear and release butterflies. It was a part of my process and learning about the butterfly life cycle. Larger butterflies such as Anise swallowtail, Monarch, and Pipevine swallowtail were easy to rear. The Chequered Skipper and Painted Lady family butterflies are more difficult to rear. They are smaller and the caterpillars well hidden in the larval plants. There were some accidents in the rearing process. Some butterflies died because of my naiveness. Barbara Deutsch who was my butterfly mentor said, ‘accidents can happen because you have been stepping into their world’. I was still distressed, but I felt I would not give up on stepping into their world.

Moreover, in taking care of baby wildlife such as squirrels and raccoons, it was difficult when a virus got into their intestines, the baby could not digest the artificial milk. The formula of the milk had to be adjusted, but not always successfully. They became thinner and smaller every meal. Those sick babies cried during nights. The nighttime temperature of their shelter would often get low at around 4:00 to 5:00 AM, and sometimes they died. I used to wake up early mornings to check the box where the baby was kept. When I found the baby was okay, it made my day.

These memories of the accidents would not fade. In 2021 I wrote to my friends in an online dialogue group [10]: ‘The ideas and images of nature are always clearly in my mind as I think about artwork and even proposals. But the actual artwork that we all do is very far from real nature, as I know it and imagine it anyway. I think of my artwork as artifice, but it is an opportunity to be deeply and consistently involved with living things and their environment. I make mistakes when I am working with ‘them’ and I hope they forgive me my wrong decisions, they may think I learn too slowly.’

Author’s Note: This article has been discussed and developed with Stewart Hannabuss, an honorary chaplain at the University of Aberdeen and an accompanist at the Northeast Scotland Music School.

ENDNOTES:

[1] Reiko Goto Collins, Ecology and Environmental Art in Public Place, Talking Tree: Won’t you take a minute and listen to the plight of nature? PhD dissertation, Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen, Scotland, 2012, 2.

[2] See the conclusion for a more complete description of each story.

[3] Thich Nhat Hanh, The Heart of Understanding: Commentaries on the Prajnaparamita Heart Sutra, Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press, 1988.

[4] The organization was founded in 1954. The current name is WildCare, 76 Albert Park Lane, San Rafael, CA 94901. https://discoverwildcare.org

[5] Many thanks to Dr. Anne Douglas, my PhD supervisor who guided me to ’empathy’ as my philosophical framework.

[6] In San Francisco, Goto and Collins lived at The Farm (Crossroads Community), an experimental community arts center on 5.5 acres under and within a freeway system. The area was converted to a theater, gallery, artist studios, and vegetable gardens. Artist Bonnie Ora Sherk was the president and founding director, 1974-1980.

[7] Oedipus is Sophocles’ tragic story not caused by human maliciousness, rather a man who fought against his destiny, foreseen by the Oracle of Delphi. See: Emily R. Wilson, Oedipus Tyrannos : a New Translation, Sources, Criticism, NY: Norton, 2022.

[8] There was never a king like Solomon. Not since the world began. Yet Solomon talked to a butterfly. As a man would talk to a man. Rudyard Kipling (Konrad Z. Lorenz, King Solomon’s Ring, A Mentor Book, 1991, p. xi).

[9] A painting image of the Bodhisatva sacrificing himself to save lion cubs, which hangs in the Tamamushi Shrine (玉虫厨å, Tamamushi no zushi) at HÅryÅ«-ji temple (608) in Nara Japan.

[10] Established in 1999, the list now has over 200 international members. https:www.ecoartnetwork.org

Goto, R., Cho En – Butterfly Garden, in ‘Sculpting with the Environment – A Natural Dialogue’, Edited by Oakes, B., Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1995.

Cho-En (Butterfly Garden), a project of the public art program San Francisco Redevelopment Agency. Artwork for the Yerba Buena Garden in San Francisco, California, U.S.A., 1993.

Cho-mu, Butterfly Dreams, funded by Dancing in the Streets and the Capp Street Project, The Walker Art Center in Minnesota, Dancing in the Streets in New York Jacobs Pillow in Lee Mass (Goto and Johanna Haigood and Zaccho Dance Theater), U.S.A., 1993.

Natsu, An, in the Open House at the Headlands Center for the Arts, Sausalito, California, U.S.A., 1989.

Haru, in the Open House at the Headlands Center for the Arts, Sausalito, California, U.S.A., 1989.

![]()

Nezumi, in 1989 Annual Exhibition of the Walter / McBean Gallery and San Francisco Art Institute, California, U.S.A., 1989.

August 7, 1989, I Shereen Kanehisa Declare That I Want to Live in Hawaii, Actually, I Declare This Everyday August 9, 1989. I Reiko Goto Declare That I Do Not Live with Human Beings I Prefer to Stay with Other Animals August 13, 1989, We Decide to Meditate Together Under These Conditions, in the Open House at the Headlands Center for the Arts, Sausalito, California (Goto and Shereen Kanehisa), U.S.A.,1989.

Goto, R., Nezumi – Rat, in LEONARDO / Current Literature, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp.490-496, Pergamon Press plc., 1989.

If I were a pigeon, Intersection for the Arts, San Francisco, California, U.S.A., 1992.

Goto, R., Collins, T., John W. Bardo Fine & Performing Arts Center, Fine Art Museum, Western Carolina, U.S.A., 2019.

Goto, R., Collins, T., Plein Air, Turchin Center for the Visual Arts, Appalachian State University, Boone, North Carolina, U.S.A., 2019.

Plein Air – Live at the Kibble Palace, at the Kibble Palace, Glasgow Botanics, Glasgow, U.K., 2017.

Goto, R., Collins, T., Plein Air, The AHRC Commons first national event Common Ground, University of York, U.K., 2016.

Goto, R., Collins, T., Sound of A Tree, Installation, ON-Neue Musik Köln, Germany, 2015.

Goto, R., Collins, T., Eden 3: Trees are the Language of Landscape, The Tent Gallery, in Art Space and Nature, Edinburgh College of Art, Evolution House, University of Edinburgh, U.K., 2013.

Goto, R. and Collins T. Plein Air: The Ethical and Aesthetic Impulse. Online publication: WEAD Spring 2011. http://weadartists.org/magazine

Goto, R., Douglas, A. and Coessens, K., Calendar Variations, a performance, and exhibition in the workshop ‘Eco-tone: Object Space Entanglements’, Nottingham Trent University, U.K., 2011.

Goto, R., Collins, T., Plein Air: The Ethical Aesthetic Impulse. Peacock Visual Arts, Aberdeen, U.K., 2010.

Goto, R., Collins, T., Headlands Artist in Residence Program, California, U.S.A., 2008.

![]()

Goto, R. Collins, T., Horse, Empathy and Sign: becoming a part of the Houyhnhnm’s environment. In Arts, Special Issue. Eds. Catarina Silva Lebre Elias, H., Cruzeiro, C, Douglas, A., Madeira, C., Basel, Switzerland: MDPI Publishing, 2022. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0752/11/2/46/htm

Goto, R., Collins, T., Lair: Mapping the Darkness, The Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Edinburgh, UK., 2019.

Goto, R., Taod Gaoisdei, The Center for Nature in Cities presents: The Caledonian Decoy, At the Intermedia Gallery, CCA, Glasgow, 2017.

Goto, R., ‘Houyhnhnm: Empathic relationship with the horse and its environment’ Ed. Bristow, T. Online publication: PAN: Philosophy, Activism, Nature, 2017.

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 13, THE ART OF EMPATHY

Published November 2022