Location: Pittsburgh, PA, USA

INTRODUCTION

ONE OF MY EARLIEST MEMORIES IS driving with my parents through Los Angeles and spotting a bomb shelter on a front lawn. I remember duck and cover exercises in junior high school, and checking where bomb shelter signs were posted in my neighborhood. The specter of the bomb hung over our lives and lurked in our dreams.

Every generation is shaped by its defining moments. For my generation, the baby boomers, it was Vietnam and the atomic bomb. The bomb irreversibly altered our relationship to the planet and it heralded the post-modern age. No longer could we take refuge in the belief that nature would wash away the sins of humanity and make us whole. Not only had we created a monster capable of destroying all life on the planet but a deus ex machina that could wipe out the natural systems that make life possible. Even if another bomb is never detonated, its offspring—nuclear energy and the resulting toxic waste—will stain the earth for thousands of years. The bomb forever tipped the balance between man and nature, and man seemingly had won. As Oppenheimer, the father of the bomb, recited after witnessing the first atomic test at Trinity site: ‘now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds’ (Bhagavad Gita).

I. UNARM, LOS ANGELES, 1982 – 1983

AFTER RECEIVING MY BFA FROM San Jose State University in 1979 my partner Stephen Moore and I headed for our hometown of Los Angeles. We occupied a loft south of downtown and ran an experimental storefront gallery, LOCUS.

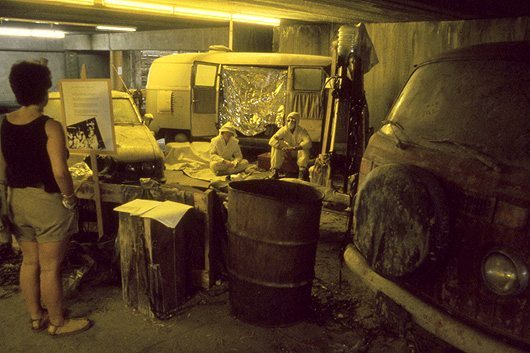

In 1982, artist Michael Davis invited us to join him and his Otis students in designing an installation and performance for a nuclear arts festival, Target L.A.: The Art of Survival. Produced by L.A. Artists for Survival under the direction of artist Cheri Gaulke, the festival challenged its audience to imagine Los Angeles as the target of a nuclear attack and envision the resulting devastation. Coinciding with the anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the weekend event occupied an abandoned parking garage in downtown L.A. and featured interactive ‘games of nuclear chance,’ artworks and installations, poetry readings, video and film, music and performances.

Our loose-knit group claimed the name UNARM and devised a tableaux of nuclear aftermath. Set in a hypothetical locale some 100 miles from ground zero, ‘Zone 7’ depicted a small group of people banding together for mutual survival in the final days following a nuclear war. Cars and debris were loosely arranged in a circle with a makeshift camp in the center. Still as mannequins, we populated the scene wearing radiation gear. Our occasional movements startled the audience and made a chilling impact.

UNARM went on to produce four performance/installations, including Neither Rain, Snow, nor Nuclear War in the lobby of the Los Angeles Federal Building. Our contribution to a larger exhibition was a post-urban living room, inspired by a U.S. Post Office memo asserting that mail would continue to be delivered even after a nuclear attack. The scene was inhabited by two figures dressed in radiation gear, a television screen displaying static, and a mound of unopened mail. Periodically, mail was delivered, adding to the pile. A week before the show was scheduled to close, the General Services Administration manager, responding to complaints from building tenants, demanded that we remove our work. The incident was covered in several newspapers, including the Los Angeles Herald Examiner.

In 1986, Stephen and I relocated to Seattle, the regional ‘backyard’ of Hanford Nuclear Reservation. It would be eight years before the bomb would reappear in our lives, and quite unexpectedly.

II. GUAM & TINIAN, NOVEMBER 1991

AFTER MY 5600-MILE, 12-HOUR JOURNEY, Stephen was predictably late. He had been living on Guam for some months designing kitchens for Club Med-type hotels that catered to Japanese tourists. Guam was an odd mix of opulent enclaves, military bases, and local communities. The government was inbred and unreliable; electricity was sporadic.

Along with sunbathing and snorkeling, Stephen wanted to explore the WWII memorials on the neighboring islands of Rota and Saipan. Given our history with UNARM, we were particularly interested in Tinian Island, where Little Boy and Fat Man were loaded into the B-29 bombers that made their way to Japan.

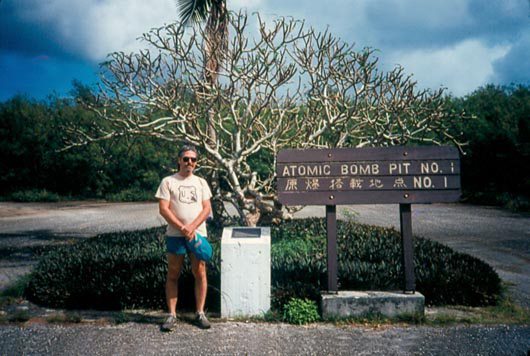

Hopping between islands required a small prop plane. Flying into Tinian, the runways of the abandoned military base appeared as scars on the land. On the fiftieth anniversary of Pearl Harbor, we set out to find the bomb pits that cradled the first atomic weapons. The site was overgrown and barely marked along the road. Each landscaped with a lone palm tree, the bomb pits sat like islands in a sea of concrete, barely keeping the jungle at bay.

Despite our difficulty in locating the site, we were not the only visitors. A minivan of Japanese tourists arrived, got out of the van, posed for a group photo, and then made their exit. I smudged the site with a bundle of sage I had brought for the purpose, whispering ‘never again.’

It wasn’t long before Stephen and I began talking about a project to expose this forgotten place where the world was forever changed. We determined to follow the trail of the bomb—from its inception to its aftermath.

III. Japan: Osaka, Kyoto, Hiroshima, Nagasaki May 1993

UNLIKE TINIAN, WHICH WE VISITED OUT OF curiosity, we traveled to Japan with a purpose—to visit key sites devastated by the bomb and to experience the culture that both commemorated and moved on from those attacks. Our host was an old friend of Stephen’s, Mano Tohei, who lived in Shimizu, about 100 miles south of Tokyo. Tohei had carefully organized our visit to include day trips to museums, gardens, and Mt. Fuji. Japan unfolded as a visual feast where ancient Buddhist shrines stood their ground between looming high rises.

En route to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we were fortunate to stay with Tohei’s extended family in Osaka. Tohei also found us a host and an apartment in Nara where we could visit this ancient city and its neighboring Kyoto. Both cities offered a bounty of temples and gardens. I was reminded that Kyoto had been on the list of potential targets for the atomic bomb. Thankfully its 3000 temples and gardens were spared.

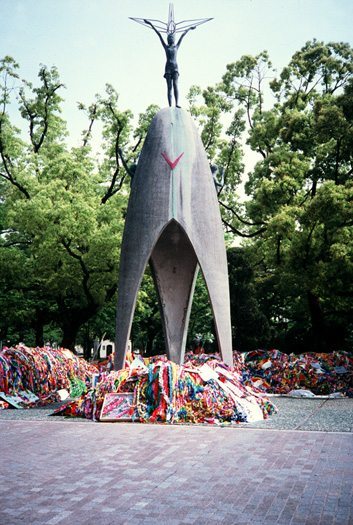

What remains in my memory of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are the monuments to those who perished on August 6 and 8, 1945. The Children’s Peace Monument in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park stands out as a stark reminder of the devastation wrought by atomic weapons. The Peace Monument was erected in response to the death of Sadako, a young girl who contracted leukemia nine years after the bombing of Hiroshima. Believing in the legend that a sick person could be healed by folding 1,000 paper cranes, Sadako began folding cranes from her hospital bed. At the time of her death, she had folded 644 cranes. At the base of the monument is the inscription: “This is our cry, This is our prayer, Peace in the world.” Children from around the world send paper cranes to be placed at this memorial.

IV. TRINITY SITE, NEW MEXICO, SEPTEMBER 2, 1993

AS PART OF THE WHITE SANDS MISSILE RANGE, Trinity Site is open only two days a year, when people journey to this depression in the sand that marks the detonation of the first atomic bomb on July 16, 1945. Two decades later, a modest monument was erected at Ground Zero, and in 1975, the site was designated a National Historic Monument.

Vendors selling books and T-shirts line the chain link fence that surrounds the site, which includes a base camp, where the scientists and support group lived; ground zero, where the bomb was set up for testing; and the McDonald ranch house, where the plutonium core for the bomb was inserted into the ‘gadget,’ as the device was called. The shock of the successful Trinity test broke windows 120 miles away, and residents of Albuquerque saw the glaring light of the nuclear explosion on the southern horizon, yet the public did not know what had occurred until after the bombs were dropped on Japan.

Trinity Site is sparse, akin to the abandoned base on Tinian Island—compelling in what is absent as much as in the historic events that took place here, which are now largely forgotten.

V. RICHLAND AND HANFORD NUCLEAR RESERVATION, WASHINGTON, MAY, 1994

IN 1943, HANFORD’S MISSION WAS TO PRODUCE plutonium for the atomic bomb. Major General Leslie R. Groves oversaw construction of the 625-square mile facility and hired DuPoint Corporation to construct the plant and the new town that would house the workers. Albin Pherson from Spokane, WA was the architect and given less than 90 days to design the entire community.

Pherson wanted to give employees a respite from the military atmosphere and boost their morale. Thus he used traditional housing and a neighborhood design that would create a feeling of normalcy. During the early years of operation, Hanford workers were required to live in Richland, and only permanent Hanford employees were allowed to reside there. Following WWII, the Cold War kept Hanford busy. By 1964, nine plutonium production reactors were operating at Hanford. The last was retired in 1991, after the fall of the Soviet Union.

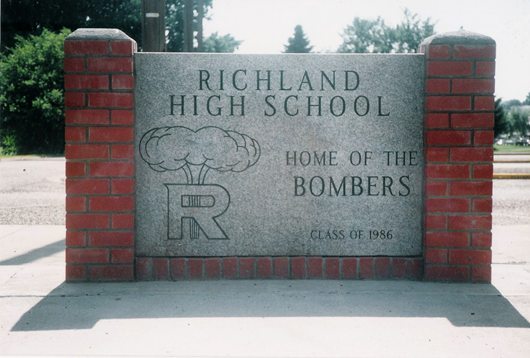

Walking through Richland, icons of the bomb dot the visual field—atomic cafes, auto body shops and brew pubs adorned with mushroom clouds, and the High School’s football team—The Bombers.

As with many places in America, towns spring up and thrive in response to a need. It is a familiar story—the promise of good jobs, safe schools, security and freedom, and knowing that what one does is for the good of the country, for the war effort. The people of Richland are proud of their history and their contribution to ending WWII. Now, following 50 years of defense work, Hanford and Richland are waging another war—the cleanup of “53 million gallons (200 million liters) of waste from plutonium processing stored in underground tanks, nearly 2,300 tons (2,087 metric tons) of spent fuel, four and a half tons (four metric tons) of plutonium, 25 million cubic feet (707,921 cubic meters) of solid waste, and 38 billion cubic feet (1.1 billion cubic meters) of contaminated soil and groundwater.” (1)

VI. FROM ATOMIC PILGRIMAGE TO ATOMIC ART

HISTORY IS RARELY SIMPLE. THERE ARE MULTIPLE and conflicting motives, rationales, immediate gains and long-term consequences. Was the development of the bomb a triumph of science over nature, a deadly weapon that put a swift end to the war, an achievement of numerous dedicated minds and hands working together for a single end? Together, these scenarios spin the heroic tale Americans were given, a story that was vehemently defended 50 years later when, in 1995, a Smithsonian exhibition and its curator were silenced for daring to question the necessity of the bomb.

Our response to Tinian, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Trinity Site and Hanford was Infinity City—a triptych of art installations we developed and exhibited over a decade:

- Infinity City: Anniversary Exhibition Venues: Washington State University, Pullman, WA, 1994; Maryhill Museum of Art, Goldendale, WA, 1995; Hunt Library, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, 2011

- Infinity City: Shadow Exhibition Venues: Mt. San Jacinto College, CA, 1996; Bellevue Art Museum, Bellevue, WA 1997 (in conjunction with the exhibition Nuclear Cities); Hunt Library, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, 2011

- Infinity City 2001 Exhibition Venues: Lycoming College, PA, 2002; Gallery Sensenci, Shimizu City, Shizuoka Pref., Japan, 2004.

Infinity City was also produced on the Internet and evolved along with the artwork and the web. It was one of the first uses of the web by artists to supplement an exhibition, providing resources and information for the communities impacted by Hanford.

The following sections draw on press releases, exhibition handlists, and journal entries of the time to suggest the complexities and contradictions that were inherent in the places we visited; to question the sanctioned narratives; and allow you, the audience, to draw your own conclusions.

VII. INFINITY CITY: EXHIBITION STATEMENT, LYCOMING COLLEGE, 2002

INFINITY CITY IS A COLLABORATIVE EXHIBITION by artists Ann T. Rosenthal and Stephen Moore that explores life in the atomic age. Since 1982, we have been involved in projects that examine the social and personal effects of living in the ‘shadow of the bomb.’ We believe the development of this weapon was a monumental event in the history of humankind, and that the stress of living in the atomic age is much underrated.

The initial part of INFINITY CITY, ‘ANNIVERSARY,’ commemorates the fiftieth anniversary of the detonation of the first atomic device on July 16, 1945. ANNIVERSARY is our response to the atomic sites that we visited, including Trinity Site in New Mexico, Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, and the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Washington State.

The second part of INFINITY CITY, ‘SHADOW,’ considers the legacy of atomic development following the end of World War II. Central to SHADOW is a chronology highlighting steps in humanity’s development, with selected events marked by etched stones.

The third part of INFINITY CITY, ‘2001’ notes milestones of America’s atomic history with anniversaries that occurred in the first year of the new millennium. Commemorative electronic posters were distributed via e-mail on each anniversary and were then posted to the INFINITY CITY web site.

Common to all three parts of INFINITY CITY is a critical reflection on nearly 60 years of atomic development with its cost to people and the environment. The first radioactive waste still sits at Hanford, leaking into the aquifer and the Columbia River. Hanford represents one of 131 sites in 39 states where some 108,000 metric tons of spent nuclear fuel and radioactive waste are awaiting ‘permanent’ disposal.

Thousands of people who have worked at these facilities producing and refining nuclear materials are awaiting the outcome of protracted lawsuits to compensate for lingering illnesses resulting from their employment.

VIII. INFINITY CITY: The Art

INFINITY CITY: ANNIVERSARY COMMEMORATES THE fiftieth anniversary of the Atomic Bomb. Its three-part foundation represents the development of the bomb (Tricity Trinity), its deployment (Eternity Ignored), and the ensuing destruction (Target Japan). Infinity City can be seen as the on-going legacy of these events—that place on the planet where each of us now lives, downwind from Ground Zero.

Selected works:

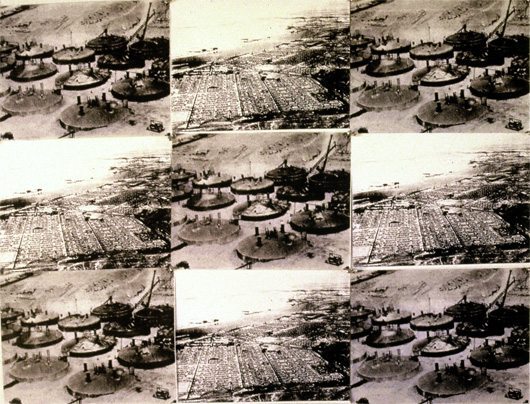

Infinity City: Hand-tint diazo process. A grid alternating between an aerial view of Hanford Nuclear Reservation in 1945 and Hanford’s nuclear waste tanks.

Eternity Ignored: Prismacolor and photocopy. Large-scale, hand-colored photocopies from photographs of the Atomic Bomb loading pits and US military installation on Tinian Island.

Banners: Photocopy transfer on muslin. Photocopies from 1945 magazines, historic photographs, and photographs taken by the artists. Images include: U.S. propaganda advertisements, duck and cover cartoons, English texts used for advertising in Japan, tourist photos of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, drawings from a Hanford Coloring Book.

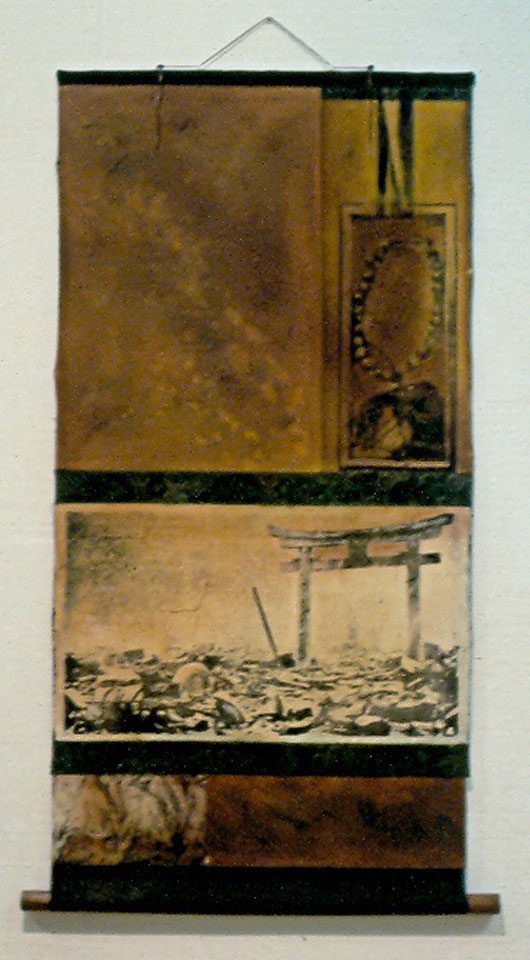

Target Japan Scrolls (2): Photocopy transfer and water-based media on canvas. Using the format of traditional Japanese scrolls, these works contrast post-bomb rubble with artifacts of American pop-culture we collected in Japan.

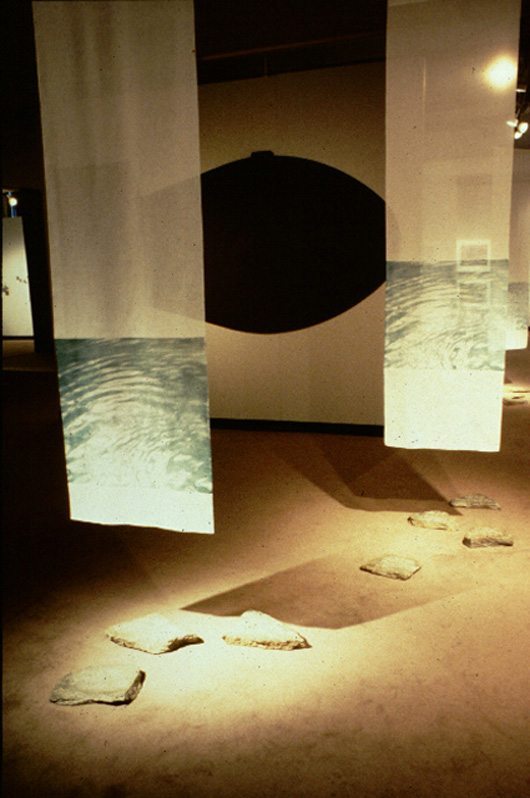

INFINITY CITY: SHADOW considers the legacy of atomic development following the end of World War II. It was comprised of three sections: A nuclear chronology (No Man’s Land); a map of Washington state (Phantom State) that highlighted nuclear-affected communities, local Native American tribes, and proposed waste transportation routes; and the three ‘Shadows’ or profiles of the first three nuclear weapons (Little Boy, Fat Man, and the Mark 17 hydrogen bomb). The stones and banners of No Man’s Land form a pathway through the exhibition with the silhouettes of the first three atomic bombs and map as a backdrop.

Selected works:

No Man’s Land: photo-lithography on cotton gauze, engraved stones. The chronology projects forward in time to estimate when the nuclear waste at Hanford will no longer be lethal (40,000 AD). It then counts back the same span of time, arriving at the last Ice Age. The chronology is comprised of engraved stones marking key dates in natural and human history, technological developments, and their resulting impact on our relationship to the natural world. Above the stones hang gauze banners printed with a pattern of moving water, referencing the Columbia River.

INFINITY CITY 2001 marked milestones in America’s nuclear heritage at the dawn of the new millennium that had anniversaries occurring in 2001. Each anniversary was commemorated through an electronic poster containing an image and a brief paragraph describing the event, which included nuclear developments, facilities, and tests. Following each email distribution, the poster was uploaded to the Infinity City web site.

Selected works:

Plutonium was first isolated March 28, 1941. Digital/web anniversary card.

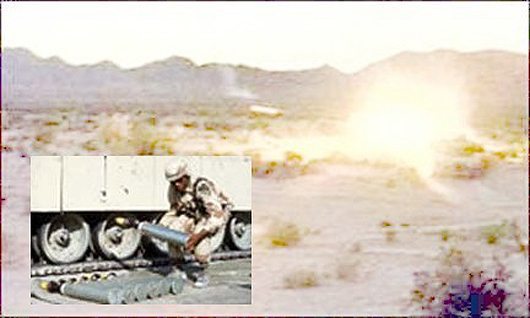

Gulf War ends February 28, 1991. Digital/web anniversary card.

IX. ENVIRONMENTAL IMPLICATIONS OF INFINITY CITY

IN THE EARLY 1990s, WE PRESENTED INFINITY CITY to the contemporary art curator at the Seattle Art Museum. He inferred that our subject was dated and that the nuclear menace was behind us. We thought his lack of vision was disturbing, and the ensuing 20 years have proved him wrong. First, there is the threat of terrorists obtaining radioactive materials for a “dirty” bomb. Second, we may have thought that Chernobyl (1986) was the fault of a failing Soviet Union; however, any such illusions were dispelled by Fukushima. The threat of terrorism or reactor meltdowns may seem remote enough to be worth the risks they pose, but nuclear waste resulting from both nuclear weapons and power plants is the elephant in the room.

A recent article in USA Today (January 18, 2012) states that plans to clean up Hanford’s 56 million gallons of nuclear waste are stalled due to “‘potential nuclear safety non-compliances’ in the design and installation of plant systems and components.” This 65-acre treatment facility, intended to “stabilize and maintain” the nuclear waste, now has a price tag of 12.3 billion, three times the original estimates and “well short of what it will cost to address the problems and finish the project.” The plant, slated to begin operations in 2011, has been pushed back to 2019. When and if operations begin, treatment of all the waste at Hanford could take as long as 30 years. Once the waste is vitrified and sealed in steel canisters, it still needs to be stored in long-term facilities. These storage sites are yet to be determined. (2) If you find this difficult to contemplate, consider the film, Into Eternity, that documents the construction of the world’s first permanent repository for long-term storage of nuclear waste, built to last 100,000 years. (3)

In his book, The End of Nature, Bill McKibben states, “The invention of nuclear weapons may actually have marked the beginning of the end of nature: we possessed, finally, the capacity to overmaster nature, to leave an indelible imprint everywhere all at once.” (4) He goes on to quote Jonathan Schell’s The Fate of the Earth: “The nuclear peril is usually seen in isolation from the threats to other forms of life and their ecosystems, but in fact it should be seen at the very center of the ecological crisis, as the cloud-covered Everest of which the more immediate, visible kinds of harm to the environment are the mere foothills.’ (5)

In developing Infinity City, we sought not only to make visible the historical, cultural, and environmental legacies of the bomb, but to contemplate how we could imagine, let alone create, a device that could annihilate all life on earth either quickly in a flash or slowly through persistent toxins working through the food chain: What does an abandoned military base in the Marianna Islands tell us about ourselves, or a storage facility holding deadly waste that must be kept safe for at least 10,000 years? What does it mean to landscape a bomb pit with a lone palm tree or name a B-29 bomber after the pilot’s mother? What does the bomb say about our relationships with one another and the abundant life on this planet?

In Vandana Shiva’s Biopiracy, she explains that the basis of ecology is the freedom of diverse species and ecosystems to self-organize: ‘A self-organizing system knows what it has to import and export in order to maintain and renew itself. Ecological stability derives from the ability of species and ecosystems to adapt, evolve, and respond.’ (6) Reliable and accurate feedback makes adaptation, self-organization, and evolution possible. In healthy ecosystems, this feedback happens naturally. However, toxins impede such feedback, prompting further human intervention, which may do more harm than good.

Translating this evolutionary model into human terms, stability in social systems derives from the ability to obtain accurate information, analyze and respond, then self-organize and evolve. Ego, politics, and profit inhibit accurate feedback and thus limit our ability to analyze and respond effectively to environmental and social threats (e.g., the politics of climate change vs. the science). Art invites contemplation and reflection, urging us to slow down and listen to the work and what it evokes in us. Art that aims to provoke social and environmental change may provide the feedback essential to evolve more sustainable communities and societies. Images and words can linger, prodding us to look deeper, inform our individual choices, and set a collective conversation in motion. That was our hope for Infinity City.

This essay is dedicated to my late partner, Stephen Moore (1939 – 2006)

End Notes:

UNARM

Some text derived from the original information flier for the exhibition and catalog for Target L.A. Original members of UNARM who participated in Zone 7: Michael Davis, Dennis Gladu, Jerry Hurowitz, Eric Moore, Stephen Moore, Hunter Reynolds Ann Rosenthal, Carol Fede Sackheim, and Janet Sorell.

Japan: Osaka, Kyoto, Hiroshima, Nagasaki

Sadako story derived from ‘The Sadako Story,’ Hiroshima International School,

Hiroshima, Japan. http://www.hiroshima-is.ac.jp/index.php?id=64

Trinity Site, Richland, and Hanford Reservation

Trinity Site, Hanford, and Richland information derived from brochures collected in our travels:

Trinity Site, U.S. DOE National Atomic Museum, 1992.

Trinity Site, White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico (date not listed).

Hanford Update: History, USDOE, prepared by Westinghouse Hanford Company

Communications Department, August 1992.

Home Blown: The history of the homes of Richland, City of Richland, 1993.

(1) Long, Michael E., ‘Half Life—The Lethal Legacy of America’s Nuclear Waste,’

National Geographic, page 4.

http://science.nationalgeographic.com/science/earth/inside-the-earth/nuclear-waste/)

From Atomic Pilgrimage to Atomic Art

On the 1995 Smithsonian exhibition of the Enola Gay for the 50th Anniversary of the Atomic Bomb, see:

Gallagher, Edward J., ‘How Do We Remember a War that We Won?’

Lehigh University http://digital.lib.lehigh.edu/trial/enola/

Infinity City

The exhibition at Lycoming College, PA was titled Toxic Trails: Tracking Fire and Water, March 7-29, 2002. Two installations were featured: Infinity City (selections from 2001 and Shadow) and Toxic Vernacular in collaboration with Steffi Domike and Suzi Meyer.

Environmental Implications

(2) Eisler, Peter, ‘Problems plague cleanup at Hanford nuclear waste site,’ in USA Today,

January 17, 2012. http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/environment/story/2012-01-25/hanford-nuclear-plutonium-cleanup/52622796/1

(3) Into Eternity, 2009. Directed by Michael Madsen, produced by Magic Hour Films.

See http://www.intoeternitythemovie.com/

(4) McKibben, Bill, The End of Nature. New York: Random House, 1989, 2006. Page 66.

(5) Schell, Jonathan, The Fate of the Earth. Stanford University Press, 2000. Page 111.

(6) Shiva, Vandana, Biopiracy: The Plunder of Nature and Knowledge. Southend Press, 1999. Pages 30-31.

Special thanks to Steffi Domike and Robert Peluso for reviewing this essay.

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 5, ATOMIC LEGACY ART

Published August 2012