Location: Berlin

INTRODUCTION

THE MUSIC OF AUSTRALIAN COMPOSER LIZA LIM is a product of an empathy-driven ecological praxis that cycles through research, creation, and reflection. It emerges from her engagement with contemporary questions of ecological science and theory, the implications of Australian indigenous knowledges, and an aesthetic sense both formed within the western classical tradition and beautifully problematized by a critique of this tradition’s presumed detachment from the world. Often composing in a process of exchange with artistic collaborators, her works open a point of contact between these ecological themes, the performers who enact her music, and the audiences that experience it. The score and the sonic experience of the music become the ground upon which further contributions to ecological theory and inquiry can be developed. Lim embraces this potential of her music; not only in performance program notes, but in theoretically-rich lectures and publications that orient one to the worlds opened by her music. To dive into the music of Liza Lim is not only an aesthetic experience of a multi-hued sonic eco-imaginary, but an encounter with the limitations of the human, even as Lim uses music, that most-human of tools, to evoke an empathetic connection with the non-human.

A prominent figure in contemporary music since the 1990s, Lim’s residency at the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin brought performances of her works to the city in the spring of 2022. Also in Berlin, I reached out to her, as I was in my own renewed phase of searching, questioning how to incorporate ecological thinking into an artistic practice shaped within the confines of western classical music training. To encounter her music and its intellectual and ethical underpinnings and implications was a gift in my own developing practice. This essay reflects on the questions raised by two works I heard in Berlin in 2022: Extinction Events and Dawn Chorus, composed in 2018 for twelve musicians, and Sex Magic, written for the flutist Claire Chase and her contrabass flute Bertha in 2020.

I. THE BEE AND THE ORCHID

IN HER KEYNOTE LECTURE for the Society of Artistic Research in 2021, ‘Beyond the eco-logical and towards the eco-sensitive,’ Lim recounts the ecological fable of the bee orchid in order to illustrate the symbiotic interplays of composer and performer, and performer-body and instrument.

‘I want to turn now to the lifeway of bees that offer me another story, another form of story-telling, of eco-sensitive assemblage pertinent to these Flute-Human becomings. The bee orchid Ophrys apifera once flourished throughout the Mediterranean region, but the bee pollinators for the orchids are now largely extinct, which leaves the plants to rely on wind-driven self-pollination, a less sustainable strategy for survival. The orchid’s form is addressing a bee that will now never arrive to close the sexual circuit between the flower and its pollen.’

Drawing on Staying with the Trouble and Donna Haraway’s reading of the web comic xkcd’s poignant retelling of the widowed symbiont, Lim continues with a nested quote of Haraway and xkcd: ‘The shape of the flower is an ‘idea of what the female bee looked like to the male bee as interpreted by a plant . The only memory of the bee is a painting by a dying flower.”

In imagining the evolution of this bee-evoking flower, Lim recounts a natural history of the flower’s embodied learning, seduction, and the mutually beneficial exchange of pollinating and nourishing. It is through this process of learning, of experimentation and a plant-insect empathy, that the flower becomes-like the bee. The relationship itself is an aesthetic exchange. This flower, as image of and invitation to a bee, serves Lim as a metaphor for her own co-creative practice of composing Sex Magic for and with the flutist Claire Chase, and her contrabass flute Bertha.

‘The orchid remembers the extinct bee through the painting of the bee-mate.

Aesthetic form emerges from generations of interaction in a feedback mechanism, through attunement, the kind that Eduardo Kohn calls ‘the pattern propagating network of living relations.’

In this metaphor, the aesthetic form that emerges is the score of musical notation that Lim writes, born of ongoing interaction and exchange with the performer Claire Chase, and Bertha, her contrabass flute. The goal is not the perfect similarity between the orchid and the bee, or the aural idea of the composer and the sound of the musician, but in the ongoing, evolving interaction between the two and the world. To pollinate and to nourish is to compose and embody the music, which in Lim’s words exists in ‘particular sensations and qualities, following and pushing back against resistances, attuning to fissures and resonances in all their inconsistencies. The music arises out of this bee – orchid environment feedback loop of attention, call it desire. The creative world of Sex Magic is this kind of iterative symbiotic activity of performance as world-making.’ (Editor’s Note: Sex Magic begins after the 25′ mark in the video below).

Though Lim’s keynote address focuses solely on the compositional process of Sex Magic, this bee-orchid fable of interspecies exchange and extinction opens the door to an understanding of Lim’s work in Extinction Event and Dawn Chorus, and a broader meditation on the interplay of music, ecological mimicry, and memory.

Lukas Shiske (percussion) & Sarah Saviet (violin), 2022. Photo credit: Camille Blake/ Maerzmusik

II. BECOMING LIKE

THE FIFTY-MINUTE Extinction Event and Dawn Chorus invites the musicians and listeners into relation with non-human beings and objects in five movements of music that trace the limitations of human sensory experience and anthropocentric forms of empathy: of being-with. As I think of Lim’s work through the fable of the orchid and the bee, my attention turns to the work’s complex relationship to inter-species and inter-object mimicry.

To return to her keynote for the Society of Artistic Research, Lim quotes Haraway’s appraisal of the xkcd ‘Bee Orchid’ cartoon, ‘it does not mistake lures for identity; it does not say the flower is exactly like the extinct insect’s genitals. Instead the flower collects up the presence for the bee aslant, in desire and mortality.’ The flower, generation by generation, becomes more like the bee, gathering its elements, its color, and its shape, even emitting compounds that inspire male bees to attempt copulation with the flower. (Martén-RodrÃguez, 2006) Though the flowers do multiply through the passion of these seduced bees, no bee is born from the meadows of amorous male bees and their floral lovers. There is a limitation at work here: the flower that became like the bee is not the bee itself.

Lim’s music examines the process of becoming like most explicitly in the work’s fourth movement, ‘Transmission’, for solo violin and snare drum. Writing in the Contemporary Music Review, Lim states ‘In ‘Transmission’ a scenario is set up where the violin/ist rehearses, teaches and transmits knowledge to the snare drum/ist who learns by imitating as best as they can despite the severe constraints of the rudimentary instrument at hand.’ Using an array of technical devices, the percussionist makes the snare drum more and more violin-like through the movement, ‘yet for all the drum’s performative virtuosity in its ‘becoming violin’, ultimately one sees and hears the limits of the mimesis, and an inevitable estrangement between the two instruments creeps in as the discrepancies add up.’

This is, in Lim’s words, a ‘theatrical’ display of mimesis, of becoming-like. As I heard the work in the Berlin Philharmonic’s Chamber Music Hall on April 7, 2022 the movement struck me as a poignant enactment of a relationship in which one yearns for an unattainable unity. The drum mimics the violin with the skillfulness and inherent clumsiness with which I might repeat bird song in the bass clef. By displaying the limitations of a being becoming-like, or feeling-for, another, Lim exposes the beauty of this human impulse to be like, to be with non-human beings. It is a transcription of the aspirations, and limitations of inter-species empathy. For our empathetic ability too is hemmed into the limitations of human senses, and the inherently limited field of imaginations available to the human mind formed within the hegemony of western thought. It is precisely these limitations which the work’s final movement traces and aims to transgress.

Whereas the fourth movement puts an artificial spotlight on imitation, the fifth movement embeds the technique in the music, as Lim composes a soundscape inspired by the songs of schools of fish at dawn. ‘Buzzing drones and low burps and rasps’ are pulled from the twelve humans and their instruments. ‘The noise of droning, buzzing fish-talk goes on; it’s deliberately boring or seems to go on for far too long. This music is not for ‘us’ but for a different audience.’ Like the drum becoming the violin, or the bass opera singer (me) becoming the bird, the soundscape, however compelling, can only go so far as to gather together aspects of fish at dawn that are identifiable to the human ear, as the orchid drew together the aspects of the female bee that are identifiable to the senses of the male bee.

The orchid becomes like the bee. The bee propagates the flower. Does the human impulse to transcribe non-human beings into human systems of knowledge, as Lim does in her fifth movement, bring about the conditions for non-humans to propagate and thrive? Here, the tragic element of the bee-orchid fable comes to mind.

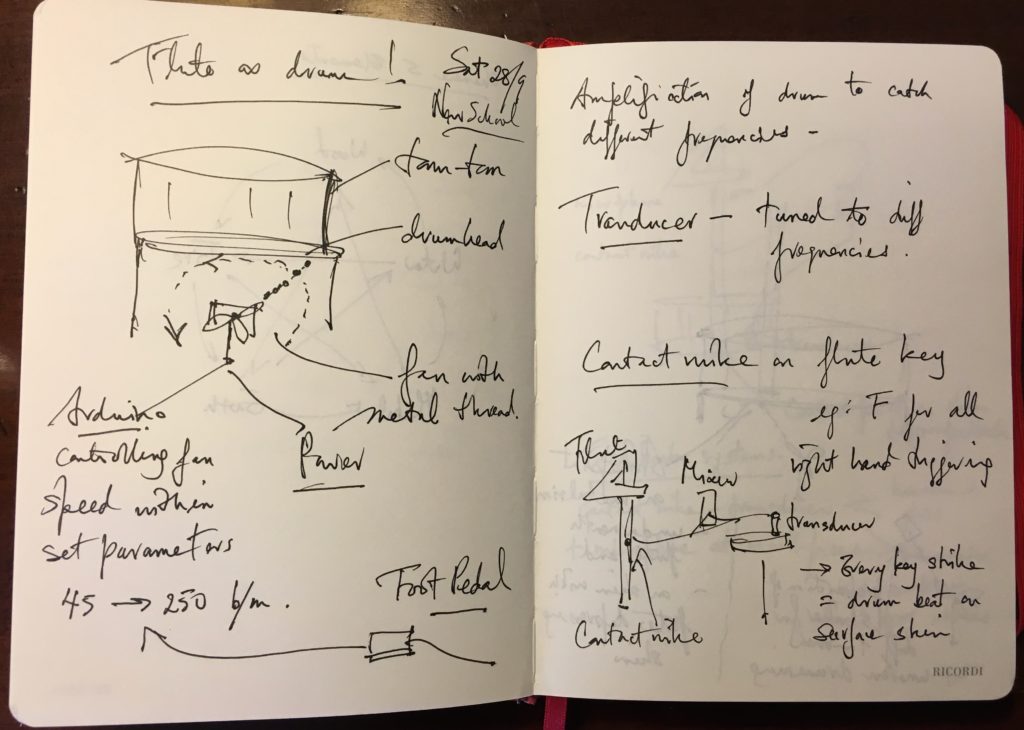

Lim’s notes and sketches of a score in progress.

III. BECOMING MEMORY

THE ORCHID BECOMES LIKE the bee. The bee propagates the flower. The bee goes extinct. To quote the xkcd comic curated in Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble, ‘the only memory of the bee is a painting by a dying flower.’ This cycle of becoming-like, only to lose the partner that one grows closer to, portends the larger ecological context of Lim’s Extinction Event and Dawn Chorus.

The fish invoked in the work’s fifth movement are the denizens of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. ‘In the ocean, rising temperatures and carbon acidification of water combine to turn the coral expanses of the Great Barrier Reef into a desert hostile to life.’ Lim writes this grim yet reality-grounded prognosis in the opening paragraph of her essay-length explanation of Extinction Events and Dawn Chorus, published in the Contemporary Music Review in 2020. With this knowledge, the fifth movement’s other-than-human soundscape becomes not only a meditation on non-human sound-worlds, but on their loss-to-be. On our present trajectory of climate collapse and ocean acidification, it is Lim’s music that will outlive the fish. Lim’s music then becomes like the orchid, in its gesture towards beings other than the human. It is the image that remains of the beings that may no longer be.

IV. REHABILITATING EMPATHY

THE STAKES OF THIS unfolding tragedy are articulated in Lim’s statement ‘what matters is not a model, but nothing less than the world,’ uttered in her keynote address, ‘Beyond the eco-logical and towards the eco-sensitive.’ For a composer emerging from the western classical music tradition, this is a profound statement. It challenges the primacy of art-making as representation, supplanting music’s supposed sublimation with Lim’s insights into Australia’s indigenous understandings of art as knowledge, art as embedded in the world. Recognizing that to articulate these forms of knowledge and practice in English is itself a colonizing act, Lim reflects on the inseparability of the natural and the cultural, the human and the non-human, within indigenous systems of knowledge and sovereignty: ‘sovereignty means the human is the land, is the language, is the song, is the animal. Is time, is law and so on . What happens to any one of those, good or ill, happens to all of them.’ Empathy is implicit within such a worldview, the worldview that Lim seeks to propagate in her musical practice.

If empathy is implicit in such forms of knowledge and the artistic practices that stem from it, I turn my attention to our isolation of the term empathy within the very discourses that bring it to the fore. It seems to me that empathy is a rehabilitative term. It is a reminder of what ought to simply be, a connective tissue surgically removed by the dichotomizing knives of western thought. It names that which ought not require naming: the simple fact of interconnectivity. As perpetrators and victims of, in Lim’s words ‘the scientific world-view that divides and holds things at a distance,’ we need the term empathy, and the artistic practices that stem from it, to overcome the violent implications of schismatic, world-dissecting and manipulating, mechanical rationalism.

While uniquely informed by indigenous thought and ecological science, Lim’s empathetic response to the ecological crises follows a standard pattern. It is an empathetic response to the world, to beings, in crisis. Lim’s empathetic reach beyond the human and into non-human worlds yields beautiful and stimulating artistic material. Like the beauty of the orchid that became like the bee that passed the gates of extinction, Lim’s love of the world may give us similar traces of the things that still are, and, if culture’s rehabilitation of empathy proves too little, too late will no longer be.

ENDNOTES

Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Lim, L. (2020). An Ecology of Time Traces in Extinction Events and Dawn Chorus. Contemporary Music Review, 39, 544-563.

Lim, L. (2020). Sex Magic. Ricordi.

Lim, L. (2021, April 7-9). Why Artistic Research matters: Beyond the eco-logical and towards the eco-sensitive. Retrieved from Research Catalogue: https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/1614960/1614943

Martén-RodrÃguez, C. B. (2006). Reproductive Assurance and the Evolution of Pollination Specialization. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 215.

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 13, THE ART OF EMPATHY

Published November 2022