In This Issue

-

Tiare Ribeaux ● Cyanovisions

-

Tabita Rezaire ● Net Decolonizing

-

Lissette Olivares ● Promethean Coevolution

-

Tina Mariane Krogh Madsen ● Body Interfaces

-

Paz Tornero ● IONI

-

Jennifer Smith ● Reva Stone Interview

-

Dr. Praba Pilar ● CO2ONIALISM in the Extractocene

-

Boryana Rossa ● Feminism and Socialism

-

Dr. Praba Pilar ● HER< E >TECH

PROMETHEAN COEVOLUTION: THE ECO MONSTROUS ASPIRATIONS OF SIN KABEZA PRODUCTIONS AND SK SYMBIOTIC

I. INTRODUCTION

Sin Kabeza Productions is a collective of activist artists dedicated to the creation and dissemination of experimental transmedia that was co-founded and is co-directed by Lissette Olivares and Cheto Castellano. We use transmedia storytelling to propose transformative architectures of society that are inspired by multispecies worldings. Our SF* performativities contend with the conflicted affects produced by the Anthropos/Anthropocene and the unfolding Sixth Great Extinction. Using situated research with plants, moss, algae, lichens, fungus, and animals that is animated by theory, music, sound, image, and corporeal movement, we move away from paradigms of human exceptionalism and towards a framework of symbiotic co-evolution in an effort to encourage radical co-habitation.

Following the death of our beloved companion toy poodle, Luk Kahlo, which forced us to contend with the frailty of life and a durational process of mourning, we became committed to exploring the relationships elaborated between species, with a parallel interest in developing technologies that allow us to become better neighbors to diverse life around and sometimes inside of us, with applications in more than human ethnography, but especially in privileging less destructive co-habitation. Intense affective encounters forged between free roaming dogs and anarchists in Chile, pariah dogs and their humans in India, an unexpected love-affair with a German hedgehog, and most recently, wildlife rehabilitation work with squirrels, white tailed deer, and raccoons in NJ, have transformed the way we approach our practice as artists. From obsessive video documentation to invented prosthetics and speculative habitats we translate affects that arise in our situated research. Recent works feature intimate worldings through in situ contact with wildlife in rehabilitation, and multispecies architectures, which refers both to innovations in constructed living spaces that adapt human dwellings for wildlife in rehabilitation, as well as a more expansive movement towards a societal and corporeal restructuring that seriously considers transformations to the way we live with diverse species.

II. GALACTORRHEA

Galactorrhea is defined as an excessive or inappropriate production of milk, and is also the name for a biological process where spontaneous production of milk occurs – this has been known to happen to women, men, and infants. In our case it wasn’t spontaneous, but the product of a durational intentionality.

Fig. 1 GALACTORRHEA TRIALS by Sin Kabeza Productions.

Galactorrhea Trials is part of Sin Kabeza’s extended engagement with transspecies kinship. We grapple with the maternal as a performance of care that has traditionally been relegated to women, and that is part of a gendered division of labor. We struggle with the maternal, and sometimes against the maternal, as an affect rooted in biological essentialism, as a practice of care that is widely believed to be the sole domain of females and gestating mothers, and consider the ambivalence and disgust that emerge when species borders are trespassed while performing as surrogate wildlife caretakers. Our intention is to destabilize our society’s reification of certain types of kinship structures (heteronormative, nuclear family, the human family) and to encourage a movement towards other types of affective relationships- performing kinship across species, across entities not necessarily related by blood or even within the same categorical kingdom, while inspiring experimentation across social imaginaries, beckoning rEvolutionary relationalities that are just around the corner.

This work emerged as I began to feel embattled with societal expectations of a body that was imagined bound to a colonial and binary biological destiny. I traversed my thirties with the consistent reminder by parents, doctors, and friends that my ability to reproduce had temporal limits and moral obligations. Faced with cascading evidence of the reality of a global climate crisis, and with the particular weight of living in the United States, I decided that my body’s reproductive drive would be steered into planned obsolescence, my womb would stay on strike in this lifetime, a decision and sacrifice of privilege that I willingly offered to the pluriverse and especially to Terra and its multitude of threatened creatures. To help me break free from the biological script I had been expected to fulfill as early as the moment I was coded a girl in my mother’s sonogram, I began inviting Castellano to help me disrupt normative narratives of reproduction. We got the chance to begin thinking about this collaboration when a wildlife rehabilitator gave us the responsibility to keep five orphaned squirrels and four raccoon kits alive, no small feat.

Fig. 2 Laboratory implements for feeding orphaned wildlife. Photo Credit: Castellano.

Fig. 3 Laboratory implements for feeding orphaned wildlife. Photo Credit: Castellano.

Our obsession with milk production stems directly from our care work with orphaned wildlife, with the desperation of keeping numerous hungry infants alive, and with a speculative approach to science and kinship. Our goal was to attempt to move beyond biological essentialism, to queer the norms that structure the expectations of our own biological processes, and to engage the productivity of our organism beyond just the propagation of our own species.

Fig. 4 Castellano introduces the outdoors to a raccoon orphan. Photo Credit: L. Olivares.

This project queered both science and family for us. We were interested in how rehabilitators were expected to respond to the growing displacement of wildlife caused by human population explosion with no formal income or budget offered by the state. They rely on a network of volunteers to perform critical care. While the ultimate goal of rehabilitation is to keep wildlife alive and wild, we could not help but be affected by the way the animals themselves interpreted our role in their care, and were active agents in the process. We became both documentarians, interested in preserving scientific data about each life we were responsible to care for, keeping detailed records of bowel movements and weights, but we could not help but also become the kind of obsessive doting kin that was proud of each milestone, making notations about when each one would try their first banana or mango, and learning the personalities of each, especially at feeding times.

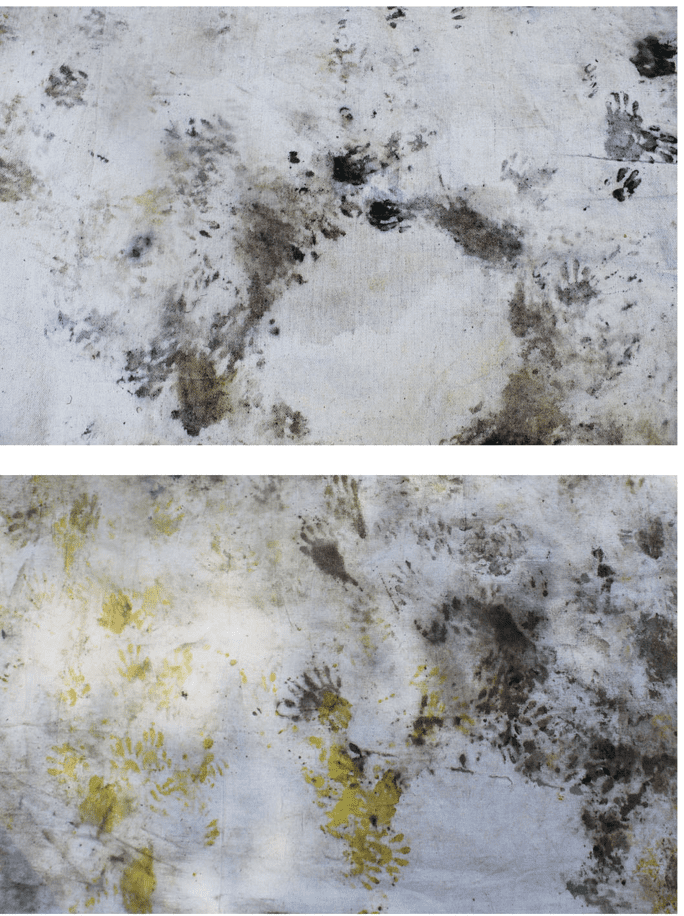

Figures 2 and 3 document m/othering though an affective scientific lens, featuring the tools we used daily to keep our critters alive, syringes and bottles for feeding. Figure 4 shows Castellano in the grass with one of our raccoon kits on an outing intended to familiarize them with local fauna. As babies raised by us we were often concerned that they would not know what to do and that our ignorance of raccoon maternal behavioral cues would lead them to run into the street. In many ways we were doomed to fail them, the world of wildlife rehabilitation does offer guidelines to help orphans adapt to the forest, however, each rehabilitator has their own methods and unfortunately, there are still very few studies about the productivity of differing methodologies. We definitely colonized their taste-buds with foods that wouldn’t grow in the deciduous forests of NJ, like dog kibble, cashews, almonds, boiled chicken, turmeric, flaxseed, marshmallows, cereals, and tropical fruits. However, it is likely for them to encounter those types of foods in the dumpsters they are known to frequent. It’s difficult but important to remember that the wild they will inhabit includes human foods from the 21st century that are enhanced with the history of colonization in the Americas, from sugar, and salt, to artificial flavoring. This experience at the same time led us to grow more scientifically interested in studying the ways that future rehabilitators and their kits might learn, like exposing them to native plants. We were surprised by their adoptive link, they wouldn’t go too far without us, and by noticing the traces of games we would invent for their play and for our own keepsake since we knew they would eventually leave the safety of our home and care.

Fig. 5 Coevolutionary games, bioArt by Orphaned Baby Raccoons (Varied Sizes, Canvas, Edible Organic Tinctures).

Fig. 6, 7 Coevolutionary games, bioArt by Orphaned Baby Raccoons (Varied Sizes, Canvas, Edible Organic Tinctures).

II. CARRIER BAGS

Long before the Anthropocene there was a language older than words that we knew how to speak and sing. With this language we spoke to the air, to the plants, to the sea, and even amongst ourselves. It was a we that existed long before the human, when flying foxes or bats, elephants and fish were recognized as our ancestors and revered as our kin. Before the rice, the wheat, and the sugarcane, the plantations, the monocrops, and the pesticides, we crossed territories armed with our most potent technology, a carrier bag.

Feminist science fiction writer Ursula Leguin reminds us of this in her Carrier bag theory of fiction, where she draws our attention to the common tropes found in the stories civilization tells:

‘We’ve all heard about all the sticks and spears and swords, the things to bash and poke and hit with, the long, hard things, but we have not heard about the thing to put things in, the container for the thing contained. That is a new story. That is news. And yet old.’ (1)

Leguin proposes the figure of a container as one that may help us to advance a feminist mode of storytelling. She traces her interest in the potentiality of the container’s work to a notebook entry titled ‘Glossary’ by Virginia Woolf, where the author proposes inverting the terms ‘hero’ and ‘heroism’ to ‘bottle’ and ‘botulism.’ Interested in Wolf’s reinvention of language as a methodology in pursuing alternate types of stories Wolf’s feminist glossary inspires Leguin to reflect upon the dangerous legacy of the Hero – of Botulism’s story, which she recodes as the ‘Ascent of Man the Hero.’

Leguin warns readers of the appeal to be found in this story, in its action and violence, which as the quote before emphasizes, is full of ‘sticks and spears and swords, the things to poke and hit with.’ In this predominant story’s stead Leguin focuses on those who have tended to become obfuscated in the service of the Hero, such as gatherers and their containers, who have figured much less prominently in the narration of human culture.

To demonstrate the way that the ‘Ascent of Man the Hero’ has blinded other stories in the history of human evolution Leguin turns to the work of anthropologist Elizabeth Fisher, who in Women’s Creation (McGraw-Hill, 1975), asserts: ‘the first cultural device was probably a recipient many theorizers feel that the earliest cultural inventions must have been a container.’

Fisher’s research on the history of cultural devices leads her to argue towards a ‘Carrier Bag Theory of Human Evolution.’ Leguin explains,

‘This theory grounds me, personally, in human culture in a way I never felt grounded before. So long as culture was explained as originating from and elaborating upon the use of long hard objects for sticking, bashing, and killing, I never thought that I had or wanted, any particular share in it. The society, the civilization they were talking about, these theoreticians, was evidently theirs; they owned it, they liked it; they were human, fully human, bashing, sticking, thrusting, killing. Wanting to be human too, I sought for evidence that I was; but if that’s what it took, to make a weapon and kill with it, then evidently I was either extremely defective as a human being, or not human at all. [ ] That’s right, they said. What you are is a woman. Possibly not human at all, certainly defective. Now be quiet while we go on telling the story of Man the Hero.’ (2)

Leguin’s humorous but damning story of how she came to feel disidentified with the way that history has been narrated by modern philosophers, and with the exclusions that this narration has sustained and made possible, allows us to view her own affinities and positionalities as a feminist, whose critical historiography enables her to critique the way that her categorization as a woman in Western discourse has been undergirded by the inhuman. Alongside many of the practitioners who have found critical openings in feminist posthumanisms, I share Leguin’s critique of modern philosophy’s hierarchical apparatus, with a few caveats. While recent critiques by scholars such as Juno Parreñas encourage us to remember that while Fisher and Leguin belong to a school of feminism that framed woman as gatherers and men as hunters, there is an anthropological counter narrative that also proposes the possibility that this division of labor is actually invented, and that early homo sapiens were not organized according to their gender roles. Like Leguin, the overwhelmingly recurrent sensation of being ‘possibly not human at all, [and] certainly defective,’ as Latinxs, as migrants, as critics of normative politics, has shaped the politics and praxis of the work we do as a collective in Sin Kabeza Productions.

I first learned about Leguin’s carrier bag theory in a course titled Multispecies Storytelling, cotaught by Donna Haraway and Anna Tsing at the History of Consciousness Department in the University of California-Santa Cruz where I pursued doctoral studies. For both these scholars Leguin’s carrier bag offered a technology of consciousness that could help us to recognize the ways that history has been colonized by the story of Man and that would enable us to begin telling stories where other agents could come to the foreground.

It is the story of the over-representation of Man, a privileged entity who has been elevated into the model of the Universal Human, a subjectivity endowed with Enlightenment’s rational thought, celebrated as an objective voice that tells the God’s eye view of history, art, and science, and whose story ascertains the Ascent of Man the Hero and the Human, that we seek to stalk with the counter technology of carrier bag storytelling.

Carrier Bags are made of and stocked with matter that matters, and are dedicated to carrying stories that have been erased in the epic histories of the Ascent of Man the Hero and the Human. They’re designed to carry fragments and traces, and are structured through weavings and knots that participate in a non-teleological telling of histories, presents, and futures, both parallel and overlapping, but always in multiplicities.

One of our most recent carrier bags can be found prototyped on the abdomen of my partner and primary collaborator, Cheto Castellano, who was inspired by the widely misunderstood and despised marsupials frequently found splayed on suburban roadways across the North East, Virginia Possums. Our training with wildlife rehabilitators taught us the importance of taking the time to stop by possum roadkill to check jills for joeys. (We encourage you to do the same, don’t forget your disposable gloves.)

For Castellano, an immigrant from South America to the United States, and a bio hacker who has ossicones himself, the stigmas against possums are just another sign of the stupidity and damage caused by ongoing settler colonialism. This native marsupial species, who has survived for 3 million years in Abya Yala, like him traveled from South to North, and is often hailed as ugly because of a hairless pink tail that reminds many of rats. (3) While this playful corporeal architecture is not intended to replace jills’ millenary biological evolution to care for evolving possum generations, Castellano offers his body as a site for orphaned respite, applying vernacular research of the body’s ability to be transformed beyond normative constructs of beauty and claims of being made in the image of God in Western monotheism. In this model below, Castellano offer the pouch to help to an ordinary house mouse being sought for extermination by panicked apartment neighbors.

Fig. 8 Marsupial Pouch with a Refugee Mouse.

The image above is a speculative prototype for a corporeal transformation that we are investigating together with body hackers, who transform the architecture of the body using surgical procedures that are used in contemporary medical practice and that have been evolving since our existence on Earth. This proposed architecture is a type of biopolitical disobedience, where the species category of the human, with its presumed hierarchy amongst life, is under attack through micropolitical technologies.

III. DEER EAR PROTOTYPES

Fig. 9 Deer Ear Prototype.

Deer Ear Prototype adapts Necomimi’s Cosplay neurowear to a technology used to enhance communication with White Tailed Deer. Originally developed to offer soothing and calming signals to orphaned fawns, the prosthesis may also be used to promote field research for those interested in communicating with White Tailed Deer. Ultimately, we believe telepathic communication with more than human species should be practiced without the need of any type of technological prosthesis, this is simply a bridging technology until we are able to reroute our neural networks in that direction.

Fig. 10 Deer Ear Prototype.

Working intimately with wildlife has been incredibly joyful, their curiosity is boundless, we have so much to learn from them. It is important to us that people shift their understanding of wildlife from purely a lens of victimization, because they certainly learned very quickly how to manipulate us and use our privilege to their advantage. As media makers, we have wondered whether our reliance on technology might be impeding our ability to connect with the myriad of vibrations being expressed by the diversity of Terran life. We have often been surprised by impossible ‘coincidences’ in the way that our non-human neighbors are able to read our feelings and thoughts and teach us lessons, often urging us to stay in the present. While there are thousands of signals being emitted by different species to establish communication, we also often wonder about telepathy, about communication occurring on other planes of consciousness not just coded by corporeal semiotics.

Deer Ear Prototype engages both corporeal semiotic language and the relay between thoughts and mechanical commands via technological prosthesis. This project emerged over the summer of 2016 when we were working with orphaned white-tailed deer, who are incredibly cute and friendly as fawns. Many are picked up by well-meaning suburban neighbors who, seeing them alone during the day, take them in to their local rehabilitator, assuming that they have done a good deed.

Unfortunately, many of these saviors are actually transforming them into orphans. Does leave their fawns alone in a place they have deemed safe during the day, and retrieve them at dusk. Due to our densely populated urban and suburban areas, those safe areas may be highly trafficked by human dwellers and neighbors. Many of these orphaned fawns are rehabilitated and released, but another large amount exhibit failure to thrive while in captivity, and despite the rehabilitator’s best efforts we saw many of these incredibly cute fawns refuse to eat and then die. While we cared for some of the weaker of the fawns, I wondered whether it might help their transition to the care of rehabilitators if we could mimic some of the calming signals they share amongst themselves. Deer Ear Protoytpe defers to the role played by ears in transmitting information amongst white tailed deers, and is coupled with the neurowear technology of Japanese Necomimi ears, which claim to translate brain waves into ear movements. We propose working together with behavioral scientists, who can help us isolate specific ear movements that this prosthesis can mimic, and that are activated through thought commands.

The Deer Ear Prototype in Figure 10 offers a techno twist to body enhancements that might help us communicate with animals differently.

IV. We Architectures

When did you learn that you were better than the soil, the oceans, the mountains, the rivers, the wind, the trees, the clouds, the rocks and minerals, the microbes, the tardigrades, the weeds, the mushrooms, the insects, the reptiles, the birds, the bats, the sloths, the sirenians, the elephants and the apes?

This question, which is always growing in its invocation of the diversity of life on planet Earth, is an affective framing mechanism to our we architectures, a series of performances and accompanying technologies that are committed to contesting anthroposupremacy, the idea that humans are superior to the rest of life on Earth, something many of us are taught by our faiths, by the legacy of rational science, and often, by our governments. We architectures deconstructs and decolonizes notions of the self that are based on modern theories of liberal individualism, proposing instead a mode of political and ecological intervention that remaps bodies and selves in relation to each other while problematizing the primacy of the category of the human as a useful strategic essentialism. Under the umbrella of we architectures we propose both a deconstruction of the human as one at the top of a species and kingdom hierarchy, (which has been already debunked in biology, as current groupings emphasize a three domain system differentiated between eukaryotes, archnea and bacteria) and instead propose a mode of storytelling where we reframe our.selves, with attention to our naturalcultural entanglements.

Our platform SK Symbiotic offers us a speculative space to perform as a bridge, retelling stories from diverse philosophical traditions, a sampling of intimate worldings gleaned from affect and communication exchanged between ourselves and our companion species, as well as a presentation of companion citations that reflect upon the influence of recent intradisciplinary research, from ecological evolutionary developmental biology (Eco Evo Devo) to queer microbial agencies in the microcosmos (Myra Hird) to considerations of how to embrace our shared interdependent transsex (Bailey Kier) to species trespasses conducted by tranimals (Hayward & Kelley), as well as attention to the history of colonization in Abya Yala and a serious deference to animist invocations amongst both organic and technological matter. (4) Our multimodal presentations feature embodied transmedia storytelling assisted by environmental experience and sound performance to work with key concepts that are introduced in accompanying lectures, employing a radical vulnerability that situates our shared struggle of living in awareness of the cascading confluences of anthroposupremacy and racialized capitalism in our troubled and turbulent past-present-future.

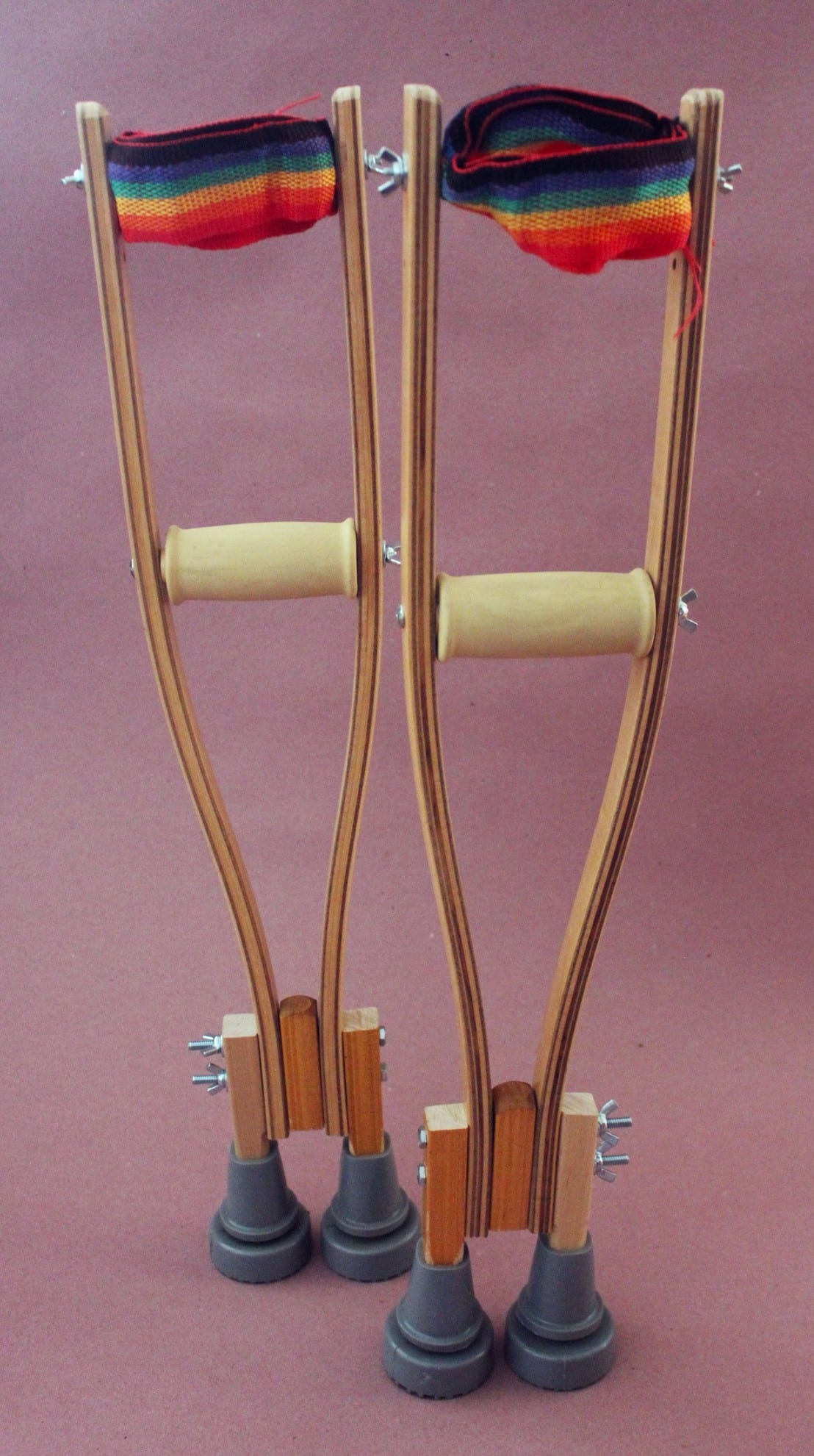

Fig.11 Quadruped Prosthetics, a Participatory We Architecture

Recently, we have accompanied our stories with a participatory technology we call Quadruped Prosthetics. Composed of repurposed medical crutches, with inviting rainbow arm inserts, we usurp and repurpose the prostheses designed for recent blockbuster films, i.e. the Dawn of the Planet of the Apes and its sequels, or the more recent Dumbo (2019). Our practice as transmedia storytellers has often sought to subvert technologies used in mainstream Hollywood cinema and refashion both the narratives told with such technologies as well as to eschew the passive consumer that is usually envisioned by the industry. While transmedia has often been touted by the neoliberal cinematic industry as a way to exacerbate the circulation of capital in media circuits, our approach to transmedia attempts to perform as an illegitimate cyborg offspring that is unfaithful to its imperial technological origins. (5) Our Quaduped Prosthetics seek to draw attention to the destructive legacy of how the story of human evolution has been framed as one of imagined superiority to the rest of life on Earth. The work of crip scholars like Sunaura Taylor further assists our storytelling by highlighting shared affects between crips and animals, both of whom are oppressed by an ableism that Taylor argues has always already been shaped by universal humanism.

Companion animals are often trained to accommodate and improve the lives of people with disabilities, however, we are also interested in inverting such a relationship, to learn how we can nurture companion species, both in and beyond the domestic realm, to relinquish and extend some of our privilege to aide their survival and enjoyment of our cohabitated space. We architectures similarly allow us to perform as service animals ourselves, teaching us to pay attention to the needs of distressed and disabled wildlife.

Fig 12. “Coming Out as a Trans*Animal: The Sympoietic Affects of We Architectures,” Performative Lecture by Lissette T. Olivares of Sin Kabeza Productions/SK Symbiotic Photo by Andrej Vasilenko, 9th Inter-format Symposium on the Fluidity of Humour and Absurdity, Nida Art Colony of Vilnius Academy of Arts, 2019.

In the recent performance Coming Out as a Trans*Animal: The Sympoietic Affects of We Architectures performed at Nida Art Colony’s 9th Interformat Symposium on the Fluidity of Humour and Absurdity in Lithuania, I opened the experience with a sound performance against a video backdrop, the throbbing rainbow warp zone joined an amplified vocoder that surged with technological transmutations of crow and raccoon calls, chanting of mantras, and a voice that shifted from robotic to high and low pitched registers affirming “I am not a man, I am not a woman, I am not a human.” With eyes veiled, I slowly walked around the venue with Quadruped Prosthetics, descending from human primate’s signature bipedal stance to an inclined pose, centering myself and bending to sit into the crutches. I stepped first with my right hand, followed by my left foot, and then my left hand followed by my right foot, remembering and aspiring towards without mimicking the weighted grace of an orangutan or an elephant, attempting to focus on a point in front of me in the darkness, trying to forget the gaze of my audience as I sought to sink into the rhythm of this new gait. A spindle of yarn spilled from my side, tracing my movement and purposefully binding the audience in a loop of rainbow colored fibers, a flexible architecture, a closed circuit, a knotted network, a constellation of shared space and time. Without telling the audience I put a magic spell on them I sealed it with laughter, requesting a collective healing for our learned anthroposupremacy.

After this witchcraft I returned to the microphone and introduced some of the works presented in this collection, introducing a corporeal architecture I am dreaming with now, which proposes a transmogrification inspired by my companion goddess and Sin Kabeza collaborator Matsya, titled, I’d Rather Be a Bitch (2019).

I WOULD RATHER BE A BITCH… (2019).

END NOTES

(1) Ursula Leguin, ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.’ The Ecocriticism Reader: Landmarks in Literacy Ecology. Ed. Cheryll Glotfelty, Harold Fromm. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press, 1996. 149-154. Print.

(2) ibid

(3) One study claims that North America is the original home to all living marsupials, while peradectids have existed for over 65 million years, the more recent (3 million years) marsupials were able to travel across Abya Yala after the Isthmus of Panama emerged. There are two opossums in the Americas, the Virginia Opossum (Didelphus virginiana), and the Southern Opossum (Didelphis marsupialis). Inés Horovitz et al. ‘Cranial Anatomy of the Earliest Marsupials and the Origin of Opposums,’ December 2009, Vol.4, Issue 12l, PLOS One. Accessed 09/01/2019 https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0008278

(4) For example, since the death of our poodle Luk, whom we have reason to believe was a Rinpoche, we have been traveling to the Himalayan region to investigate sacred histories, sites, and performances. Our studies were especially influenced by residencies with Kathmandu’s Center for Shamanistic Studies and with its founder Mohan Rai and the jhankris Donaxing and Parvati Rai. We were led to Rai through the mourning rites we followed after Luk’s death in 2011 and which led us to create the project.

(5) For a further discussion of how transmedia is being defined by our practice please see Jian Chen and Lissette Olivares, ‘Transmedia,’ Keywords, Transgender Studies Quarterly, 2015. Pp 45-247.