Location: Winnipeg, Canada

ON AN ICY DECEMBER day in Winnipeg, Canada I was lucky enough to spend a couple of hours with Reva Stone talking about life and her art practice.

Winnipeg is a funny place. It is a small-ish city with a strong arts community that has produced many internationally renowned artists. Reva Stone is one of those artists.

In a city with a population of around 800,000 the arts community is very connected. Stone is an artist who is creating groundbreaking new media work, while at the same time mentoring artists in the community through artist-run centres such as Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art and Video Pool Media Arts Centre.

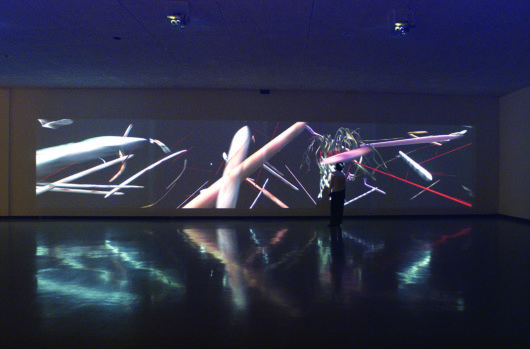

RADIOPTICON, Reva Stone, 2015. Photo credit: William Eakin.

At the time of our visit she was the artist-in-residence at the University of Manitoba School of Art and sharing her work with the next generation of Winnipeg artists. Although the entire community is aware of Stone’s amazing work it can be easy to take for granted. When someone moves to Winnipeg or is visiting and asks if I know Reva Stone or if I can arrange a meeting, and when I answer that it wouldn’t be a problem, you can see their excitement. Having access to this astounding woman reminds me how lucky we are to have Stone residing in our small city.

This interview provides a glimpse into how fortunate we are to have this amazing artist in our community and how she consistently leads the charge for artists working in new media.

ABOUT REVA STONE

IMAGINAL EXPRESSION, Reva Stone, 2004. Photo credit: Ernest Mayer.

REVA STONE’S WORK EXAMINES the mediation between our bodies and the technologies that are altering how we interact with the world. She engages with forms of digital technologies to initiate discourse about how biotechnological and robotic practices are impacting the very nature of being human. In her current work, Stone is investigating the ideologies driving the development of unmanned aerial vehicles.

She has received many awards, including the 2017 Distinguished Alumni Award from the University of Manitoba, the 2015 Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts, and an honourable mention from Life 5.0: Art & Artificial Life International Competition, Fundación Telefónica, Madrid, Spain. She has exhibited widely in Canada, the US and Europe, presented at symposia, and published in journals such as ‘Second Nature: the International Journal of Creative Media’.

JENNIFER SMITH: How many years have you been working as an artist, and how many years have you focused on technology in your practice?

REVA STONE: I graduated in 1985 from the University of Manitoba. At that time I still thought I was going to be a painter, but I was starting to nail things to my paintings and wanting to make them move. It was a slippery slope for the first five years. It was after that, in 1990, when I applied for a Canada Council (for the Arts] exploration grant and a Manitoba Arts Council grant for something I had no idea how to do. I had a bit of advice and I kept trying to make a budget. A computer was $5,000 at the time—just the computer! Eventually I submitted the two applications and I got both! Honestly, I had not even turned on a computer before that.

I got the computer and I turned it on with my heart beating really fast and I learned how to use it, which took me a year or two. I worked with a programmer and made the piece I said I was going to make and it really is a transition piece for me. It’s called Legacy and is partly painted and part technology. It is a built room exploring what I was observing about video games and children. This was at the same time as the Gulf War and it was my first piece. Gulf war clips got put in with the things that I was seeing on television about children’s toys and stereotypes, which are still the same today, but were new for me to think about then. It was finished in 1992, and that is when my practice, as it is today, started.

I spent about ten years looking at the body and the way it is represented in medical imaging technology. I have looked at many different ideas of how technology is affecting how we live in the world.

JS: I have read that you are considered to be the first woman to work with technology based in Canada.

IMAGINAL EXPRESSION DETAIL, Reva Stone, 2004. Photo credit: Ernest Mayer

RS: It’s not true. At the time I started research for my grant, one had to give examples of similar work being done. There was Nell Tenhaaf that I knew of, and there were a few other women working with art and technology. Because I needed to do research and I needed to find out more about who was working like this, I spoke with some of these women and was asked, ‘Why are you jumping on the bandwagon?’ Clearly there were enough women working with art and technology that I could be asked this question. There were maybe four or five other women that I knew of.

JS: You said that you have used the support of programmers. Can you talk about how it has been working with programmers to achieve your vision?

RS: Well, I worked with programmers most of the time. I tried to learn, but I was aware of the limitations of the tools available. I wanted to work with people who knew C++ well and I was lucky in finding them. I found people who were doing regular everyday programming jobs but wanted to think outside of the box. At one point I actually made contact with the University of Manitoba robotics professor, Jacky Baltes, and he recommended students that he felt could work and think laterally. I worked with a number of his students, including Andrew Winton, who I’ve worked with for the past eight years.

Technology has changed so much too. At one time you could not go on the internet and find the code for camera visioning, but now you can just cut and paste it. I had to work with someone who could invent his own system for my work.

JS: I am interested in learning about your connections to women in the arts community. You have been involved with Mentoring Artists for Women’s Art over the years as someone who pioneered what is common today in terms of the way women are working within media arts and new media. I’m wondering how you felt doing something different than what the rest of the community of women artists were doing in the same city? How does it feels to have such a big influence on the generation of women artists following in your footsteps?

RS: First of all, I was some kind of oddball because I didn’t realize I was working that differently than the community. I just was driven by my ideas so much and the possibilities of being able to say, ‘What if?’ The community where I live has been amazing for the support that everybody gives each other.

When I was finishing University, the first MAWA mentorship program was coming into being and I was in the first program. My mentor was Aganetha Dyck, who was a very established artist. I think the biggest thing I got out of that program was the ability to take risks and not worry about where the money was coming from. I was told if I had a good idea I would be able to find the money and that was true. Risk-taking helped me discover how much I liked the unknown. Being in over my head was very exciting at the beginning. I never thought about the fact that I might be a role model until I got a little older.

JS: You mentioned working with stereotypes in your first project, was your video ‘Generation’ part of that first installation?

RS: Yes

JS: That video has been shown as a stand alone video, but was made for the installation. I am interested when you talk about how the stereotypes you explored in the 1980’s remain present in today’s media.

RS: When I recently saw that video that I made in 1988, it hit me how things have not changed much. The little girls on the programs in their sparkly pink costumes are the same that my seven year old granddaughter sees today. I have twin grandchildren and I saw how they could be neutrally gendered up until they were about four years old. One has become a pinky-pink girl and the other has become the math and science guy. They used to have boys and girls sections at the toy store. For awhile they had the toy sections all put together—blended—but now we’re back to boys and girls sections. One thing that has really changed is gendered sexualization, for example little girls wanting bras when they are five and six years old.

JS: That leads to my questions about the way you progressed with using the body as part of your work. I have noticed that there are two ways that you represent the body:

1) showing how the presence of people changes the way the artwork is seen

2) as unsexualized digital representations of the body

Examples of each are: Carnevale 3.0 , a robot that looks like a child and moves around based on body heat, and Imaginal Expression, which is microscopic images of portions of the body, that are not the same based on how the room is occupied. I am interested in knowing more about how you view the connections of people within the space you’re using, but also people within the artwork you are making.

CARNEVALE, Reva Stone, 2002. Photo credit: Ernest Mayer.

RS: When I made a robot that looked like a young girl, I was coming out of the phase where I was looking at video games which over the top sexualized woman. I purposefully made a surrogate of myself as a young girl, neutral and non-sexualized. After this piece I wanted to take a lot of the body out of the picture.

JS: What are the connections for you between technology and the human body?

CARNEVALE, Reva Stone, 2002. Photo credit: Ernest Mayer.

RS: Early on I was really interested in posthumanism, the idea that we were going to replace human bodies entirely, which was talked about with hyperbole at that point. I did a lot of reading about it and I could see that technology was really changing things. I can now see what I was reading about then coming into being. There’s talk about using technology to grow new limbs or exchanging your shoulder joint if you have a problem. You’ll be able to alter yourself over and over again and have a life. It was the promise of immortality that drove all of this.

What I’m currently reading about is sensors that can measure every aspect of our bodies allowing for self-diagnosis. I’m trying to figure out how to make work about this, which I still see it as a drive for some sort of perfection. I read somewhere that it all started with the anxiety caused by the bathroom scale. Now we have all these things to measure ourselves, like how many steps we take, and whether we’re doing it everyday. We feel guilty about not doing the 10,000 steps a day.

JS: At one point knitting needles and backstrap looms were technologies, quite different from electronic technologies today. Do you see this progression as similar to today’s technological advancements?

RS: No, technology is making life much more complicated now.

JS: I read the idea in the feminist tEChnOart curatorial statement by Dr. Praba Pilar, Danielle Siembieda, and Isabella La Rocca, that technology and humans are evolving together. I’m wondering if this concept relates to your practice? A lot of your recent work has focused on the destruction that technology plays in our society as opposed to it being used it for better purposes. It’s interesting to think that we’re building technology that grows with our knowledge. But are we questioning enough how technology is being used?

ERASURE (still from video), Reva Stone, 2019.

RS: I am always questioning how technology is being used. The work that I’m showing next, called Erasure, is about five different components of drone technology and UAV’s (unmanned aerial vehicles) and how altered the world is. Things have disappeared. We used to know about drone attacks, they would be in the newspapers, but we don’t hear about them anymore. I realized that I had been looking at erasure, what we erase from the picture when we talk about war, or about any technological issue. I’ve been making work about the areas that are being erased, this is new thinking for me.

ERASURE (still from video), Reva Stone, 2019.

JS: Do you find exploring new technologies challenging? Your first computer was $5000 and was an expensive risk. Now, with technology being cheaper, how do you weigh those risk factors when thinking about what to take on next?

RS: To be honest I don’t know what the next thing is. I thought it was 3D printing at one point because you can print anything! But, I am less and less excited by what I see. For me the really important part is the initial research, when I’m learning about things and reading philosophy and social commentary. I mostly read a lot of cultural studies in the areas I find interesting then I observe. I put it aside for a while, then later I make the work.

JS: How do you navigate the ethics of technology? How do you feel about the technologies you explore and what they stand for? At times you will have to purchase technology that doesn’t follow best practices in manufacturing, recycling or disposal; or supports an undesirable industry such as a drone that might support the military.

RS: I was once giving a talk at a teachers’ inservice. They were interested in working with technology and kids and I told them that I ordered a lot of my stuff from China. A woman jumped on me asking how I could work with China because they don’t respect intellectual property. She was so condemning of me and I was taken aback, until I thought for a minute that everything is made where someone is being exploited.

JS: Do you feel your work questions the ethics of the technology?

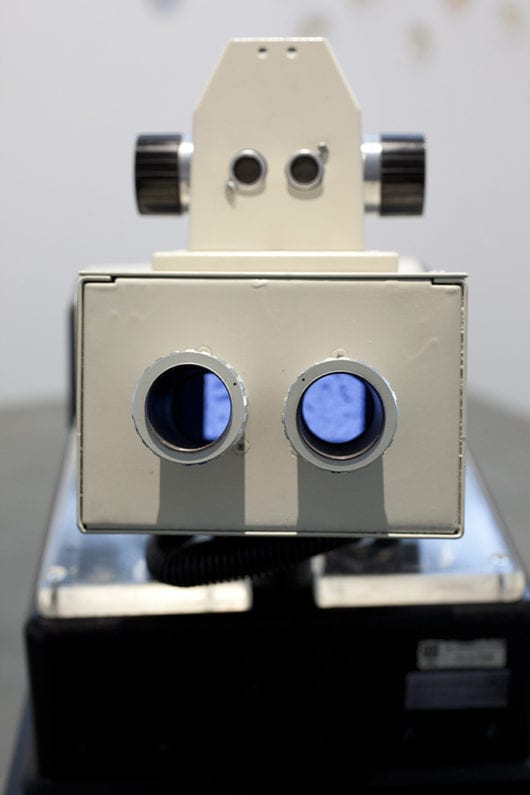

MICROFORGE, Reva Stone, 2013. Photo Credit: William Eakin.

RS: Not always. I was just thinking about the piece, Microforge, that I made for an exhibit in Winnipeg called Toxicity. It was about the exploitation of workers who are taking apart western technology at personal risk to their health, such as little children working with toxic material to make a few dollars.

JS: Tell me your thoughts on the aesthetics of your work.

RS: Recently I was talking with someone who is writing an article about my work and they said my work is beautiful but creepy. I don’t know how conscious I was of doing that, but until I get that creep factor, I’m not happy with the work. It is off-putting, makes you question what you’re seeing and suggests that there is a technological failure going on.

JS: You talk a lot about failure and choosing to exhibit a work that is not working properly, or projects that don’t work, that you have put aside or leave behind.

RS: When you take risks you are going to have failures. I have things that I never could make work because the technology wasn’t there yet. But that didn’t happen very often. I would always take it as a personal failure, and I think most people do that. It took me awhile to realize that I am basically prototyping. I don’t have a huge research and development department behind me; I am not attached to a university. I’m going to have failure and I have to make that failure integral to my work. I can live with it better now than before.

JS: What’s next?

PORTAL 6, Reva Stone, 2011-2019.

RS: I have an exhibit at the University of Manitoba School of Art Gallery until April 27, 2019. I’m going to have a show at Video Pool Media Arts Centre in August 2019, where I’m going to exhibit the cell phone project that I have never been able to show. I got it to work after ten years of working on it. I wondered if the work would still be relevant; it has a completely different meaning now and I have re-edited some of the video. I have nine phones trying to interact with me and have a conversation. When I recently turned it on I felt like I was in the middle of social media, and I didn’t expect that. My original intention was about networking, bringing it into today. Networking then and now are different.

JS: You have two exhibits and are there new projects in the works?

RS: I’m finishing some work and looking at new material. Sometimes I wake-up with new ideas and then I discard them. I write everything down, but I don’t know where I am going next.