Rhodessa Jones is an actress, teacher, director, writer, and the founding director of the Medea Project, a performance workshop designed to achieve personal and social transformation with incarcerated women and women living with HIV. Her published works include A Beginner’s Guide to Community-Based Arts. She was recently invited to be a Montgomery Fellow at Dartmouth College. Writer Denny Riley, a long-time friend, interviewed her for Peace & Planet News.

Denny Riley:

The term Black Lives Matter entered the lexicon a while ago, but now has come to the front. Many people and many corporations are changing attitudes and logos. Black Lives Matter is half of every news report. I know you were born in 1948 into less than affluent surroundings. I’d like to know what kind of civil rights progress you’ve seen in your time.

Rhodessa Jones:

The kind of progress I’ve seen is more reflected in my mother. She loved that she could vote. She didn’t want to mail in her vote. She wanted to be at the polls. She wanted to stand among the people, as she would say. She’d tell us this, and then she would go into the whole, painful history of watching my mother was taken to a lynching when she was nine years old. She remembered being taken to a lynching of a family of seven brothers. This was in Georgia. She and her family were gathered up by the white folks, put on wagons. They took all the black folks who lived in that area, you know, to see the lynching. I remember Mama telling us something happened, something happened, and she saw seven brothers castrated. She saw the pregnant wife of one of the brothers begging for her husband’s life. One of the white men stomped the baby out of this woman. My Mama was a nine-year-old girl and she said they weren’t allowed to look away. The man had a shotgun pointed at them. They were forced to watch this, you know, and these were people she knew, neighbor people begging for their lives. And she had to witness their murder as a way of telling us that we had no rights. We had no power. There’s a great line from Margaret Walker’s Harriet Tubman poem, where she writes, ‘Stand in the field Harriet; Stand alone and still; I am still the overseer, mad enough to kill. This is slavery Harriet, bend beneath the lash. This is slavery Harriet bow to poor white trash.’ And that’s what my mother was living.

And then for her to come along in the sixties and be able to vote as well as to be able to file a claim, a complaint against an institution or our landlord. My mother was good at it. She sued people to demonstrate her rights. My mama had only a fourth-grade education but my brother Azel gave her a wonderful copy of Angela Davis’ biography. She’d sit at the kitchen table underlining passages and mouthing some of the words.

Yet a whole lot hasn’t changed at all. When we think about the death of George Floyd we see it woke the country to what has always been going on.

I love my country. I love America, even with the killings still going on. The police are murdering people right now. George Floyd died on the 25th of May and already the police are involved in four questionable deaths. And everybody can see it. I’m an activist, and I love all kinds of people. I’ve been blessed to have all types of friends and community. Right now, there are people that I love who I have to check. Such as one friend of mine, she told me that she didn’t see color. A white woman. We’re talking about all of what’s going on and she goes, ‘Oh Rho, I love you so much I don’t even see color.’ The world put the brakes on. I went, ‘Wait a minute, wait a minute.’ She goes, ‘I just love you Rho.’ I said, ‘If you don’t see color you don’t see me. You insult me if you tell me you don’t see color. You come to my shows and you tell me you love it when I’m up there when I’m pouring it out, and you tell me you wish the show could go on forever. What do you think that show is? That’s my color. That’s part of being a colored woman in the 21st century. A colored woman who has to find a way to hold it all together.’

James Baldwin said, ‘To be black and conscious in America is to be in a constant state of rage.’

We can’t live like that. So we birthed the blues. We got rap. We got the walk. We got the talk. And it’s all part of how we cope. How we live.

I am so grateful for Black Lives Matter. The flags are flying everywhere. It’s too bad it had to come to this, but if we can embrace it, if we all can embrace Black Lives Matter, it can change all our lives. It’s a shame that in this great country we have to say, Hey, y’all, black lives matter. And then you have a whole group of people saying, well, all lives matter. Of course, all lives matter, but why am I standing here screaming at the top of my lungs that black lives matter? Why? Let’s examine this. Let’s unpack this historical trauma. And that’s what we’re doing right now with Black Lives Matter.

Why are we at this place? We hear about the cops resigning because they can’t use the choke hold. I hear this and it makes me want to disappear. I want to go live in Trinidad or Tobago, but I can’t, as long as people gather and I can share with them our collective history so we can move the whole thing forward. The Black Lives Matter movement at least encourages us to examine where we are.

DR: Could you describe the way the Jones family lived and your progress through to the point where you’re known as a successful artist, awarded various honors including a U.S.A. Fellow and honorary doctorate in Fine Arts, a published playwright, and other tributes, still you are often pigeonholed as simply a Black artist. In the beginning few would have imagined your life taking this road.

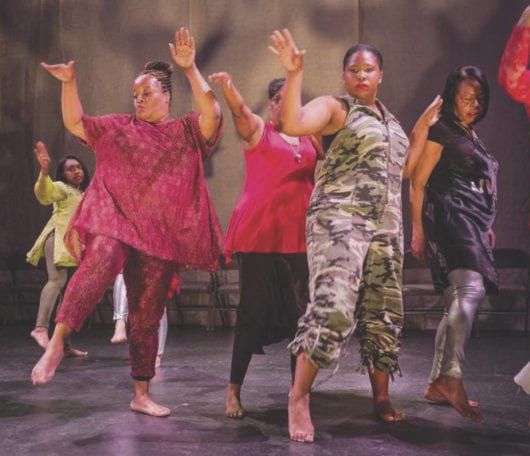

MEDEA PROJECT in performance.

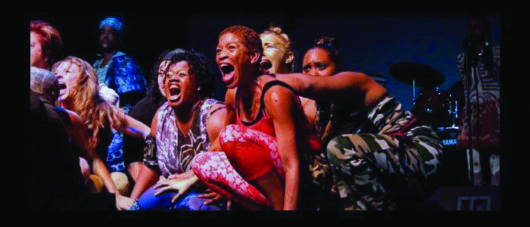

MEDEA PROJECT in performance.

RJ: I’m a migrant child. My mother and father were migrant workers. Actually, we all were. If your parents pick, you pick. At one point, my father had a crew of more than a hundred people. In 1948, the year I was born, Daddy set out to do this, because in America, if you could pull a crew together and get contracts from all up and down the Eastern states, you could make a living as a gypsy caravan. It was fantastic. That’s one way to see it, to travel up and down the Eastern seaboard. But the winters were hard after we left Florida. We ended up on a dirt road in upstate New York. My parents wanted us to get an education and they knew we’d have to get off the migration. At that point, there were nine of us and we were poor. As Nikki Giovanni would say, ‘I didn’t know I was so poor,’ We were kind of living on the outskirts of America, a black family snowed in on a dirt road. I loved even then the idea of being an outsider. I think part of my journey has been that I didn’t know any better. I’m going to do this. I’m going to do that. My sister Flossie and I went with two white guys to the first Vietnam War moratorium in Washington. They were veterans. They served, as people say. We were in the streets. I tell people, when they ask me about protesting, that I went to the very first big one. They ask how’d I do that? I tell them it was the company I was keeping, the man I was involved with, you, Riley.

Rhodessa Jones with Denny Riley, 1970.

Your brother was a Franciscan friar in D.C. and we stayed at the friary. Flossie was just along for the ride, but she had a ball. It was the beginning of a cultural revolution. But back to your question, the scenario you’re creating. I had a baby. I was a mother before I was a woman. I had a baby at 16 and thank God my parents said, ‘You’re not going to give this baby away.’ We had land and we could grow food. And it was like, well we were very, very poor. I mean, one winter was so heavy they dropped the cheese and cornmeal and all that stuff in by plane because we couldn’t get out.

DR: Your brothers Bill and Steve and Gus told me about going out with a sled to find wooden packing crates and any other scrap wood to take home for firewood. They had socks on their hands because they didn’t have gloves, and the white boys in Wayland would kid them about it. And your brothers would say, no, we’re building a fort.

RJ: Yeah. Nobody in that part of New York was wealthy. Wayland was a poor hamlet. German and Italian immigrants. Even there black folks were the monkeys. We were the ones who weren’t quite humans, so the other white boys could say all kinds of stuff. The other side of that was that when my sisters and I were like 12, 13 and 14, we moved into Wayland. My mother and father had decided that they were going to open a restaurant. And at night the fathers of kids I knew from the school would be knocking on the door downstairs, wanting to know if they could buy one of us girls. As if we were whores. And my father was beside himself. He knew these men. They had kids too. Yeah, that happened too, that happened.

I’m reminded of Toni Morrison saying that her grandmother told the grandfather, we have to leave here. We have to leave the South because the white boys are circling. She had beautiful young daughters and these guys would come and just sit and look at them. If you were smart, you just got the hell out of there. You know? So it was very, very layered, because from another angle I’m so glad I grew up there. I was educated there. I mean, I write a great letter. I enjoy reading. I can add. I can subtract. I’ve read the classics, Victor Hugo, the Brontë sisters, Joseph Conrad, J.D. Salinger. I mean, that was a part of our learning. We were all studying this in school and my brothers and sisters and I loved it. When I moved to the city, I looked like a snob because I spoke well. I had a handle on language. And I could talk to white people truthfully, which was a whole thing. ‘You can talk to white people?’ I had a white boyfriend. He worked in a soup kitchen and had endless radical theories that made sense to me. That was you, Denny. You’d say you got all your best lines from me. This shaped me, moved me toward activism. I tell people my life has been very mythical. I feel like I was sent. I didn’t go to art school. I didn’t say, okay, I’m going to be an activist. My grandmother was a great storyteller.

Then Riley, you and I and my daughter Saundra woke during a snowy winter night with our apartment on fire. We made it out almost okay and left town, headed south and camped our way down to Central America and lived on a beach in Costa Rica. From there we came to San Francisco. California at that time was the enchanted state. My brother Azel moved out here and wrote a musical, Port Royal Sound, about the freeing of the first slaves in the Civil War. It’s a musical. It all came out of who we were. It wasn’t like Azel said ‘I’m going to be a great playwright.’ Azel was a Buddhist and he thought, how do I examine my reality through the lens of theater? And so we formed The Jones Company and did this musical about the freeing of the first slaves and the Civil War. And all of us were in it. There was money for the arts. I loved Isadora Duncan. She touched something in me, her early bearings as a citizen of the West Coast. I began to dance with Tumbleweed dance company. All of the other dancers were white girls who’d gone to good colleges. We toured all over the States and Europe. Then I was asked to go into the San Francisco jails and teach aerobics to incarcerated women.

I got in there and looked around and was like, what does incarceration have to do with rehabilitation? What does this jail have to do with saving the lives of women? But I kept going because I was curious, and I realized there were so many black and brown women arrested because of their relationships to men. I come from a family of 12 brothers and sisters, so I know something about Black men being incarcerated, but I had no idea there were so many women in lockdown. In most cases it was due simply to association with men. Being caught in the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong guy. Women would just be taken along to jail. ‘Come on, bitch. You’re going too, because you’re in this house with him, that’s why.’

The realization I brought into the jails and all I could say to the women coming from my own experience was that you have a right to a life. The women there just felt like they lost the contest. It was like, I’m not good. I got busted or I’m a junkie, or because I’m a junkie I’m a whore, or I’m a whore and I’m a mother. I go out and turn tricks so my kids can have milk and cereal.

They were so down on themselves. I just knew instinctively that we all have a right to a life, and that had a lot to do with how I came up from that dirt road in upstate New York. I would ask the women what happened. Because I had a handle on literature and some sense of myself, and my grandmother, mother, and my father were all great storytellers, and I saw that these women had stories. I got the idea of these women acting out their predicaments, and once they started, I saw real passion, I felt real theater. That’s how the Medea Project was formed.

MEDEA PROJECT, Rhodessa Jones.

MEDEA PROJECT, Rhodessa Jones.

To be down on yourself was a way to deal with the pain and to deal with the idea of being not counted. You could almost ignore the pain because you thought you were supposed to have it. I still struggle with that myself. I think that white supremacy affects all of us. Like if most people say you’re no good, you’re no good. You don’t matter. I’m going to hang your brother. I’m gonna rape your sister and I don’t even care if you tell. Who gives a shit? At the same time, what does that do to the white guy who’s saying this? How entirely full of misery and hatred must he be? For people of color there’s a lot of shucking and jiving that goes along with simply staying alive, like Stepin Fetchit, you know, you play that part. It may be degrading but it gives you a little space to move around. What does the white supremacist filled with righteous hatred do?

My daughter would say in street language, ‘I see you.’ I see you, I know you, I’ll remember you. Right now I don’t have the power, but I see what’s going on. And then the people that are killed because they look at a cop eye to eye and go, yeah, I’m looking at you. Emmett Till. Emmett Till was just a kid who supposedly saw a pretty white lady and whistled. Later, we found out none of that happened. She lied, but they came into his grandparents’ house and just took this kid away. And he was never seen alive again. But in the words of David Chappelle, nobody was ready for ‘what a fucking gangster his mother Mamie Till was!’

She demanded, ‘Leave the coffin open. I want them to see what they did to my baby.’ And Chappelle feels like that began the action of the civil rights movement. It’s like because the whole world saw this 14-year-old boy who had been murdered, you know, just slaughtered.

Back to your question about how has civil rights influenced my life. Estella, my mother, was a woman who had lived without rights for so long and had lost her father to white supremacy and nevertheless, she would still say, ‘Y’all have rights, you know?’

My grandfather, Walden, was a brakeman on the Southern Railroad, just outside of Savannah. Grandpa Walden was coming home from work at two in the morning. Can you imagine he was a brakeman on the train? This was a real job. So he’s walking through this area and there’s only one house on the road. Two young white girls live there. They said a Black man, who they found later was a white man in blackface, looked in the window at them, but the posse had gone out on horses with shotguns. They came up on my grandfather and they said, ‘Look, nigga, if you value your life, you leave now.’ And he asked, ‘Can I go and say goodbye?’ They said, ‘No, you have to leave the state of Georgia now.’ And my grandfather left and didn’t return for years and years and years. In the wake of that, my grandmother felt abandoned. She had nine children to raise on her own. My mother’s dream of being a nurse ended; my mother had a father who had a regular job on the railroad so she could dream of being a nurse and all of a sudden, he’s gone. Finally, he gets word to them but he’s afraid to come back. So my grandmother had to raise nine children by herself. This is like the turn of the century. She would live and work on a plantation where life hadn’t changed much from slavery. But if she saw a better job on another plantation, she’d tell the plantation owner she was leaving for a better job. The owners would say, no you’re not. She’d say yes, I am. One owner beat my grandmother because she was leaving. My grandmother said, ‘Unless you kill me, I’m leaving here.’ He left my grandmother in a pile in the yard, but she left. The only freedom she had was that she could leave so she did what she wanted. She was always looking for a better job. She had to feed her children, and also, she had that fury, she was furious.

She moved all over Georgia, ended up in Pavo where my mother met my father. My grandmother bought a shotgun and kept it loaded. She made a name for herself. ‘You’re a crazy nigga, you know?’ And she was like, ‘Yeah, I’m crazy. Step up on my yard and see how crazy I am.’ It must have been awful. My grandmother lost all of her teeth. She was big and black. She wasn’t pretty and soft with golden skin and soft hair. She was a big, broad black woman who took care of her family. She was a midwife. She was a root worker. She did all these things to take care of that family of children and still lost some of them to smallpox. She was married five times. She was filled with grist. It sustains me to know this. How do they say it? I am standing on the shoulders of the generations who came before.

Originally published by Peace and Planet News, the quarterly newspaper of New York City Veterans For Peace and the Vietnam Full Disclosure project, peaceandplanetnews.org.