Location: Tacoma, Washington, USA

HEALED PORT, digital collage, Beverly Naidus, 2016.

HEALED PORT, digital collage, Beverly Naidus, 2016.

I. INTRODUCTION

AS I GAZE OUT OF MY studio window, I look out upon the traditional territory of the Puyallup people http://www.puyallup-tribe.com/ourtribe/, one of many Coast Salish communities that sits on the shores of the Salish Sea (colonizer name: Puget Sound). The landscape is crowded with the incursions of Petro-capitalism: huge container ships, lines of cranes, and tanks filled with fossil fuels and toxic chemicals. They stretch from one end of the horizon to the other. Thankfully, the purple mountains in the distance remind me of the impermanence of what I am surveying. In this extraordinary moment of pandemic threats, economic collapse, police violence, hate crimes, floods, fires, and climate emergency, my heart is witnessing and experiencing a collective uprising of grief, rage and joyous solidarity.

It is in that spirit of heart, solidarity and transformation that I want to share this story of working as an artist in collaboration with activists, tribal people, students, colleagues and community members to awaken local people to the dangers of the Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) refinery being built by a Australian owned multi-national corporation, Puget Sound Energy (PSE), on unceded tribal land in the (settler named) Tacoma tide flats. The Puyallup people, upon whose lands the city of Tacoma was founded, have not ceded the traditional fishing grounds that the LNG plant is being built upon, and its construction violates the Medicine Creak Treaty of 1854.

The tribe has continually survived challenges caused by the extractive enterprises of settlers. Sadly, the legacy of environmental racism persists.

II. COMING TO TERMS WITH THE AROMA OF TACOMA

IN 2003, I SMELLED TACOMA FOR the first time. It was not pleasant and with my history of environmental illness, I perceived this odor as a toxic threat. I was being interviewed for a faculty position: the first full-time, tenure-track art position at an innovative, non-traditional, interdisciplinary, urban-serving, state university. My hosts, the hiring committee, provided me with accommodations in a high-rise hotel downtown. I took one look at the expansive panorama of the industrial Port of Tacoma with smokestacks belching, and I said out loud ‘there’s no way that I’m taking this job.’

But, in the two days of interviews, I was told repeatedly that I could teach whatever I wanted and create a unique interdisciplinary studio arts curriculum with a focus on social change, and that I could live on an island, with a 15-minute ferry commute. After so many years of low wages for my teaching and no health insurance, I signed the contract.

Our journey around the Salish Sea has lasted 17 years now. The first eight years were spent on Vashon Island, where I learned about the legacy of the copper smelter, ASARCO, based in north Tacoma until 1985. ASARCO’s plume of arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury severely polluted the soils and attacked the health of residents in the region. https://www.thenewstribune.com/news/local/article43503663.html

By 2011, soon after I’d completed an eco-art project to demonstrate how to heal damaged soil with permaculture design, we moved to Seattle. However within a few years, the high-tech industry’s takeover of the city raised the price of real estate to such an extent that it became too expensive for us. We recognized, despite many concerns, that it was time to come to terms with Tacoma.

Teaching on the UW Tacoma campus for 12 years, I learned that the causes of the occasionally stinky air of Tacoma were a combination of low tide, the sulfurous stench of the pulp mill, and the prevailing winds. I was tired of the people who would smirk and hold their noses when Tacoma was mentioned. I recognized that I had internalized some of this strange form of ‘environmental’ shame.

While there is no way to escape the toxins that have been released by late capitalism, certain communities have been targeted as sites because they are perceived as expendable.This is not only true of the developing world, but is evident in many areas of the U.S. Areas where large populations of working poor and people of color are particularly at risk of environmental racism and classism. Tacoma, with all its superfund sites (https://www.cerc.usgs.gov/orda_docs/CaseDetails?ID=954), sadly ranks high in this regard.

While our economic reality instigated our move to Tacoma, what made our choice attractive was the discovery, via social media, that activist groups in Tacoma were successfully fighting the building of a methanol refinery. The groups involved, particularly Redefine Tacoma, inspired us to look at ways we could contribute to this movement, and in 2016, we put down our roots in this racially diverse, traditionally working-class, and proudly gritty town.

Poster designed by Beverly Naidus, digital collage, 2020

Poster designed by Beverly Naidus, digital collage, 2020

III. CORRUPTION AND MAKING CHANGE IRRESISTIBLE

THE CITY OF TACOMA HAS A very challenging and corrupt history. Most of the port lies in territory of the Puyallup people. It was promised to them in the Medicine Creek Treaty of 1854, and that treaty has been violated thousands of times in the subsequent years. If one looks at early images (mostly paintings and drawings) of the region, one can see the lush estuary of the Puyallup River running through the tide flats and fed by the glaciers of Mt. Tahoma (the colonizer name is Mt. Rainier). Now the whole area is filled with superfund sites the result of industrialization and corporate disregard for the health of the residents and the environment. The river empties into Commencement Bay, one of the most polluted bodies of water in the world. The once plentiful sea life that includes Orcas and salmon, and the ecosystem that supports them, has been extremely challenged by the dumping of industrial waste into the soil and water.

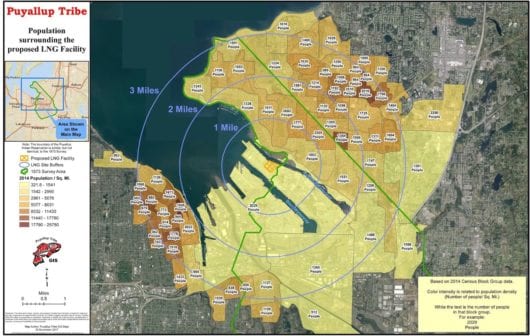

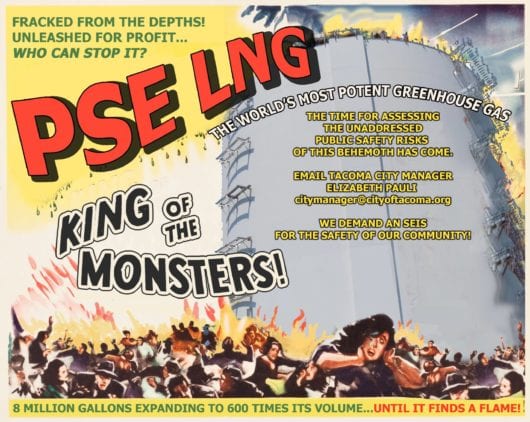

Soon after arriving in Tacoma, I learned about Puget Sound Energy’s (PSE) plan to build a liquified natural gas (LNG) refinery in the port. Many residents did not understand that liquified natural gas was different from the methanol plant that had not succeeded due to the hard work of activists. Educating the public about the dangers of eight million gallons of LNG has been a big task. Many people think that LNG is what they use in their homes. and PSE has been spending millions of dollars to ‘green wash’ the public into believing that this liquified natural gas is a clean, green fuel. It is not. The refinery will rely on fracked gas piped in from British Columbia and elsewhere. The stated intention is to use this fuel for very limited shipping needs, for tankers who bring goods to Alaska and to China. However the public will pay for this, not only with increased rates, but with their health. Methane gases would be released daily. As the well-respected tribal elder and long-time activist Ramona Bennett has stated, ‘Tacoma would smell like a giant fart 24/7.’ If and when an accident occurs (LNG is highly volatile) projections of the blast zone indicate that it will be 12.5 miles wide, destroying all of Tacoma and the surrounding communities. Originally the Puyallup tribe did a study of the potential blast zone being 3.5 miles wide (see photo) but the Tacoma Fire Department’s study reveals a much more dramatic possibility. The whole operation is a profoundly dangerous climate-heating waste of the rate payers’ money, but the problem remains that most of the public does not know about it.

Map of the potential 3 mile blast zone created by the Puyallup Tribe, 2018; The Tacoma Fire Dept’s research (previously hidden) predicts a 12 mile radius for the blast zone.

Map of the potential 3 mile blast zone created by the Puyallup Tribe, 2018; The Tacoma Fire Dept’s research (previously hidden) predicts a 12 mile radius for the blast zone.

When we first moved to Tacoma, I discovered a wonderful coalition of environmental activists (including 350 Tacoma) and local tribal members working tirelessly to educate the public; showing up and speaking at city council meetings, submitting petitions, getting involved in local elections, doing social media posts, organizing marches and direct actions, and being arrested to stop the building of the refinery. Still my neighbors, as well as my students and colleagues at UW Tacoma, seemed uninformed, and our city council was not shifting their allegiances from the fossil fuel industry to that of their constituency. We assumed that they were getting a payoff under the table from PSE. One of the campaigns to inform residents included signage that stated in bold letters that we were living in the blast zone with a website link. https://www.frackno253.com/

After attending a dinner with a group of committed activists, I was offered one of these signs to put it up in our front yard. I was curious to see if it would provoke thought or conversation with the people who walk past our home. After a few months, I decided that there needed to be a better way to reach out to the community. I realized that for most of my neighbors this information would either fall on deaf ears or not motivate them to act. In all of my years of doing interactive and participatory art projects about disturbing things, I’d learned that without a personal story or humor, audiences often retreat into numbness or denial.. I recognized that the campaign might benefit from a different approach, one that made reclaiming the port for the needs and desires of the community irresistible.

When I was a young artist, expressing my concern about the state of the world through my work was my way to find others who felt as I did. With that community, I could address questions about why we put up with this situation, but it was not enough for me. I grew impatient with always addressing the same questions.

It took three converging experiences to shift my art practice into a different realm; one where I was willing to take the risk to imagine ways to transform the messes I was examining. The first was a meditation practice that I began with Thich Nhat Hanh; he taught us about the benefits of watering the positive seeds within our consciousness as a strategy for being more grounded and effective in daily life. Secondly, my experiences working with Joanna Macy, an environmental activist and Buddhist scholar, gave me tools to process grief, pain, anger, and despair and shift that energy into action. Third, as a teaching artist at the Institute for Social Ecology I was exposed to the concept of reconstructive visions: how to envision and then move towards creating the world we want to live in. I began to brainstorm what a radical reframing of our community’s concerns might look like and decided to call on a group of interested local artists and activists to help me think through where we needed to go.

IV. ARTS BRIDGING COMMUNITIES

Anonymous Tribal Member’s collage, 2018, South Sound Sustainability Expo, Tacoma, WA. Photo by Erika Bartlett.

Anonymous Tribal Member’s collage, 2018, South Sound Sustainability Expo, Tacoma, WA. Photo by Erika Bartlett.

IN THE FALL OF 2017 I, with two other colleagues, received a grant for a new campus organization, Arts Bridging Communities. I proposed to lead meetings to develop a community art project that focused on healing the Port of Tacoma. I brought to those meetings the following questions: What would the process of reimagining the Port of Tacoma look like? How could we best collaborate with the community to create this vision? Would facilitating art workshops bring a diverse cohort on board to make their own images? How could the communities’ dreams for a fossil fuel free and greener future be seen by a large audience? Would our art project have the impact we wanted on the powers that be?

We had several meetings to discuss our intentions and how to make them manifest. I shared lessons I’d learned from permaculture design. It might be possible to heal the superfund sites using plants and mushrooms as part of the remediation process. We discussed the complex challenges of green energy, repurposing the industrial landscape, and community gardens. About 20 people came to these meetings out of curiosity, and ultimately three of us took on the work. We decided that two of us would facilitate artmaking workshops at public events and the third person would work on the process of projecting the digitized images onto buildings and creating video documentation of these at public screenings. I suggested the name Extreme Makeover: The Creative Remediation of a Superfund Site and we moved forward with that title.

In the spring and summer of 2018, Erika Bartlett and I led two workshops, one at the South Sound Sustainability Festival and the other at the first ever, ‘Oceanfest,’ in Tacoma. Both events had a great turnout. Dozens of collaged, drawn, and painted images were made by adults and children, reimagining the port and the refinery tank as so many things unoccupied by fossil fuels: an aquarium, a solar power hub, a skate park, housing, and a multi-level food forest. One former student was even compelled to work with the material outside of the formal workshops and created a series of compelling digital images revisioning the refinery tank as a regenerative container for growing mushrooms and a hemp farm.

V. 350 TACOMA

Richard Vincek, Drawing & Collage, 11×8.5′, 2019.

IN EARLY 2019, I DECIDED to deepen the ripple effect of the project by partnering with local activists to facilitate a series of workshops about reimagining the port. The team at 350 Tacoma were welcoming of my proposal. https://www.350tacoma.org/ They already had an artful activism group doing a variety of projects (including banners, puppets, and placards for demonstrations), both to engage the public in local issues and to teach people about the principles of the 350 organization: to keep fossil fuels in the ground, to divest of fossil fuels as investments, to bring our current parts per million of carbon in the atmosphere (414 ppm) back to 350 ppm.

As we discussed my proposal to offer art workshops, we explored what might inspire the wider public to reimagine our port free of fossil fuels, healed from toxins via permaculture design, resilient to the rising sea levels, filled with eco-art and truly green forms of energy, and with a restored Puyallup estuary. We discussed the contradictions inherent in ‘green energy,’ acknowledging that even green energies require resources that have serious impacts on ecosystems in the developing world.

I attended a screening of the film, Ancestral Waters, created by Native Daily Network, which details the activism of Puyallup tribal members to stop the LNG facility. During the panel discussion, I learned that the tribe wants remediation of the Puyallup estuary to be a primary goal. The speakers explained that they were running out of salmon, saying that it was estimated that salmon would disappear after four years, and without the salmon the tribe, who are salmon people, would disappear. I understood the urgency and started making my own images of a revived estuary.

South Sound Sustainability Expo, 2018, Tacoma, WA. Photo by Erika Bartlett.

South Sound Sustainability Expo, 2018, Tacoma, WA. Photo by Erika Bartlett.

After more discussion with 350 Tacoma, I renamed the project, Extreme Makeover: Reimagining the Port of Tacoma Free of Fossil Fuels and scheduled workshops in their new storefront space. I created the posters and 350T did the marketing via social media and elsewhere. They invited me to be part of their artful activism team. As someone who has never found political meetings that nourishing, I was surprised to discover that I really enjoyed this group and looked forward to our time together.

Extreme Makeover workshop 2019, 350 Tacoma storefront, Tacoma, WA. Photo by Daniel Villa.

Extreme Makeover workshop 2019, 350 Tacoma storefront, Tacoma, WA. Photo by Daniel Villa.

Over the course of many months in 2019, I ran 2-hour workshops in the storefront space. We had a generous amount of art supplies provided by the grant and people came with great enthusiasm to brainstorm how to transform the environmental damage of the port and make the port resilient to rising sea levels. The workshops drew in a true cross-section of the community: long time activists, students, retired people, immigrants, recent arrivals to the area, and children.

Collage by Erika Bartlett, 11’x8.5′ 2018.

In each workshop, people shared a bit about themselves and what brought them there. I told everyone to invite their inner four-year old to come out and play during the workshop. In this way, they could free themselves of the self-critique that can freeze the creative energies of both practicing artists and those who don’t identify as artists. After that, I led a guided meditation to help people relax and connect with their whole body followed by a visualization exercise that helped them look at something toxic, traumatic, or disturbing in the port, and imagine a way to heal it. I asked them to visualize on a screen on the inside of their foreheads, the colors, shapes, textures, spaces, lighting, etc. of the remediated landscape. Most people chose to repurpose the LNG refinery tank, but others transformed the port into an estuary with leaping salmon, and gardens. We closed the workshop with a sharing of the images and how to make those imaginings come true by initiating projects and stepping up our activism.

Extreme Makeover workshop 2019, 350 Tacoma storefront, Tacoma, WA. Photo by Daniel Villa.

Extreme Makeover workshop 2019, 350 Tacoma storefront, Tacoma, WA. Photo by Daniel Villa.

The folks at 350T hung the work produced in the workshops on their walls. I digitized every image and we began to brainstorm where and how to project the finished work.

Digital art by John Carlton, variable sizes, 2019.

Digital art by John Carlton, variable sizes, 2019.

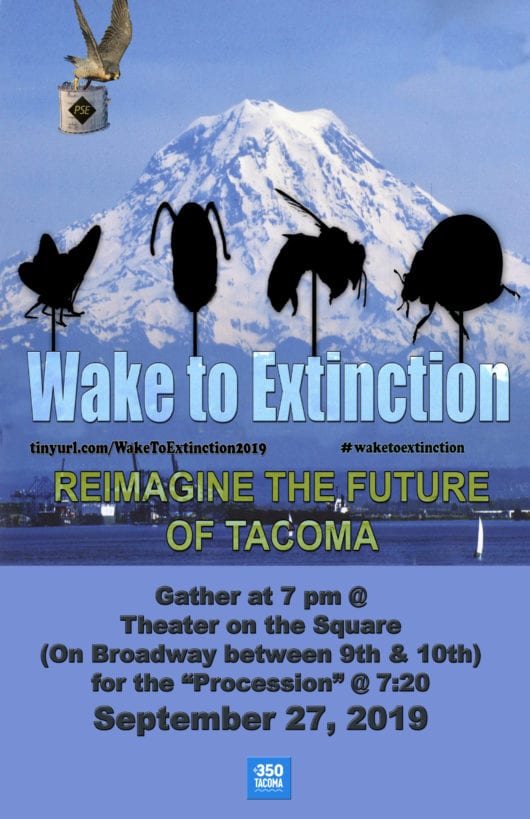

VI. WAKE TO EXTINCTION

IN THE SUMMER OF 2019, the artful activism team hosted some workshops on making luminaries with the goal of having a procession honoring the extinction of insects. While it was not my normal jam, I found that I really enjoyed decorating a mutant monarch butterfly. Our brainstorming about the procession became quite elaborate. We decided to culminate the procession, named ‘Wake to Extinction,’ with a projection of the images created in all my workshops. We did plenty of scouting to find good walls for projecting the images and got permission from the Tacoma Art Museum to project on their exterior wall. We also networked with Metro Parks to do another iteration of the projections in an area of the shoreline, Ruston Way, where the LNG container was visible to people walking and biking on the park’s walkway.

Poster by Beverly Naidus, 2019.

Unfortunately, as we got closer to the date of our event, the weather turned. At the last minute, we had to revise our plans. An outdoor event became an indoor event. We moved the entire evenings program to the art building on campus, a renovated church that could accommodate over a hundred people with large luminaries. A beautiful eulogy to the insects going extinct, written and read by 350T member, Barb Turner, moved the ‘congregation’ to tears. The workshop images were projected on a large screen in the main studio space (the former sanctuary of the church).

Jeanne Cummings holding the Mutant Monarch, Wake to Extinction, 2019.

As the winds died down, the luminaries were taken outside for a short procession through the area near the university, a part of town that has little pedestrian or car traffic on a Friday night. The whole event was well documented with video, so it did have a life on social media with a larger audience. Nevertheless, the main goal of the project was to reach members of the Tacoma community who knew nothing about the LNG and that intention was not realized. We decided to do it once the rainy season was over in the Spring 2020, and in the meantime, I would host more workshops to gather more images.

The Procession of Luminaries, Wake to Extinction, Tacoma, 2019.

The Procession of Luminaries, Wake to Extinction, Tacoma, 2019.

VII. THEN THE PANDEMIC

A WEEK AFTER THE ‘WAKE’ I hosted another workshop in early October. It was well attended, and more work was produced. Soon after, I left for Chongqing, China to be a guest eco-artist for a week at the Sichuan Art Institute. Visiting China gave me new insights into how to facilitate my workshops. I was totally refreshed by the students and faculty I met and their determination to clean up the toxic messes created by rapid industrialization in their communities.

I returned to the States in late October, barely dodging the Chinese version of the virus pandemic. I decided to pause the workshops through the holiday months and return to offering workshops in February. The last live workshop was held on February 29h of 2020 and after that I retooled the workshops to go online. Thus far, I have offered four workshops online, with participants zooming in from all over North America. I have changed the title twice, first to Extreme Makeover: Reimagining the World We Want and then to Extreme Makeover: Reimagining the Now.

In each zoom session, we discuss the connections between the virus, the climate emergency, systemic racism, and the collapse of so many systems including health care and education. People share how they are navigating this moment. Participants use their own supplies, and can draw, paint, collage, create texts, make music, sew, use found objects, or create altars. I tell people a bit about the history of the project and then invite folks to look at how the collapse offers huge possibilities for building structures, environments and communities that are healthy, caring, and sharing. People meditate and develop the imagery with the tools they’ve brought. After 45 minutes, we share what we’ve created and talk about how we can enact some of the ideas we’ve had.

In this new iteration of the Extreme Makeover workshops, I’ve been excited by the energy people bring to this work. There is a great longing for having some control over the outcomes of this time and to create new initiatives within the limitations of the pandemic. I end by sharing many of positive projects that are occurring in many parts of the world as neighbors rise to respond to the needs in their communities.

VIII. CONCLUSION

THE VISION THAT HELD THIS PROJECT from its inception, to transform a threat and a challenge into a possibility that is rich with potential, continues to inform this work. It has not yet entered public space in the ways that were first conceived, to reach those who are uninformed, misinformed, or too busy and overwhelmed to register what is being shaped to endanger them, their families, and friends. That particular audience has been elusive thus far, but with the help of the 350 network, local, regional and national, as well as Native Daily Network, our creative brainstorming is expanding; a new film, street interventions, interactive altars, and projection projects are back on the table.

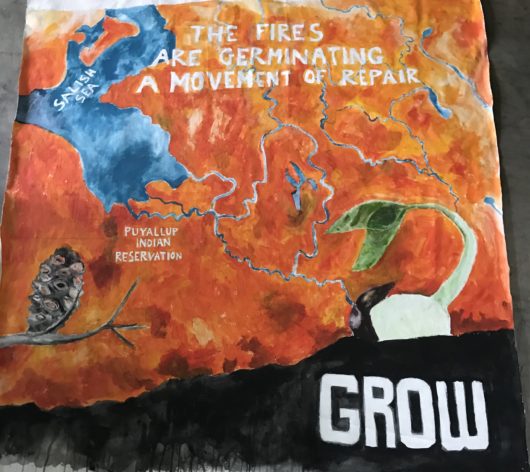

Saiyare and Elle’s panel in process. 350 Tacoma, October 2020.

Since I recently left my full-time faculty position at the university, I have the bandwidth to take on more activist work. After being invited into the 350T leadership circle, I initiated a window art project in the storefront space that has languished during the pandemic for lack of use. As part of a team of five artists (the max we can have in the space at once under COVID protocols, we have brainstormed imagery and text to engage and inspire the public. We are working with a few guiding concepts: what seeds of repair can be germinated in the fires and what new and healthier systems are emerging from the smoke. Our canvas panels will fill all seven windows in October 2020. The panels are being designed to be easily reused.

Finally, I have another big project to embrace. I will be taking the socially engaged art courses created for UWT students online so that people around the world will have access to that content, as part of the non-profit, SEEDS (Social Ecology Education and Demonstration School). My partner, Bob Spivey and I, co-directors of this organization, will eventually open up a storefront, with a lending library, workshop space, and become a hub for making art about climate and racial justice. This is the vision that we have carried for a long time and we are seeking out a collective of passionate people who will join us to make the project thrive.

Beverly Naidus’s panel in process, 350 Tacoma, 2020.

Beverly Naidus’s panel in process, 350 Tacoma, 2020.