Location: San Diego, CA

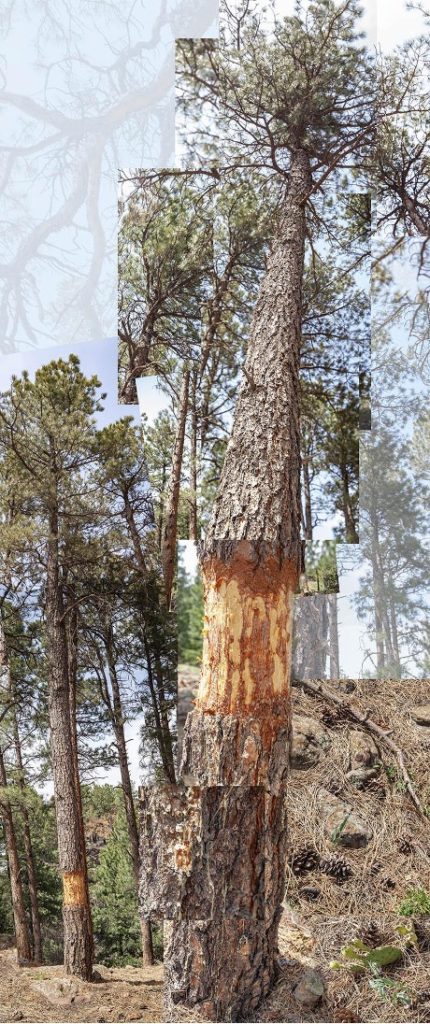

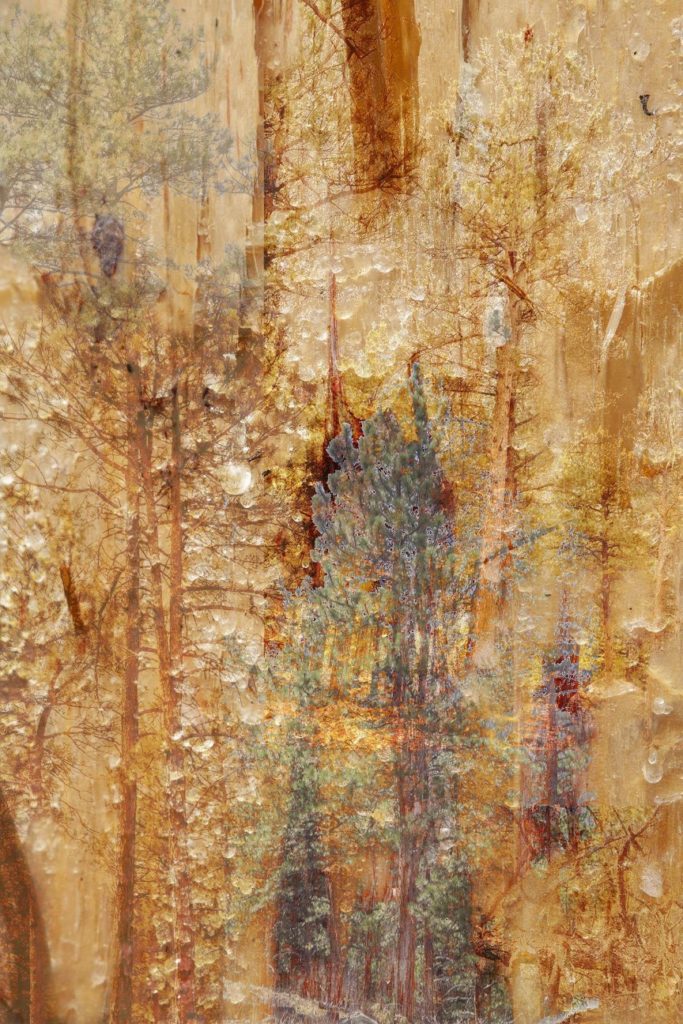

Artist’s note: All images were created from photographs taken on or near the Shanahan Trail in Boulder, CO in April of 2022. The photomontages offer a variety of glimpses and perspectives. They are a labor of love, an effort to convey the visceral sense and vibrancy of life that I experienced.

INTRODUCTION

OVER THE PAST DECADE I have been walking with dying trees in Southern California, following the same trails repeatedly, bearing witness to the increasing losses of trees due to the intertwined impacts of urbanization, globalization, and climate change. Last spring, I was fortunate to receive a Lenz fellowship from Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado to continue my work on this project, focusing on how Buddhist practice could inform working with ecological grief. During my four months there, I frequented the foothills, where the Rocky Mountains rise sharply from the western edge of the city. Before winter turned into spring, a small fire, known as the NCAR fire, burned about 200 acres. I invite you to accompany me on my spring walks to this burned area and along the Shanahan Trail, where in the previous year foresters had thinned the trees to lessen the severity of future fires.1

I. APRIL 9, 2022

Dear Tree,

Your yellow band caught my eye and drew me to you. I stood beneath the shelter of your branches, feeling your presence, and slowly reached out to touch the band oozing with sticky sap, trying to synchronize my breath with yours, but the girdle all the way around your trunk prevented your flow.

Oh Tree, I am so sorry. Your needles are so green. This will be a slow death. The girdle around your trunk has sliced through your veins, your phloem, so that nutrients can no longer flow up from your roots to support new growth, nor can the sugars that you create through the process of photosynthesis flow down to your roots. Instead, your sap is dribbling down your trunk, your bark encrusted with your blood. There is no tourniquet to apply to this wound. You will bleed slowly until you die. Oh, dear Tree, I weep with you.

Your girdle is part of a strategy the foresters use to prevent the conflagrations that are killing your kin, including your relatives that have stood for hundreds of years. They have felled some of your neighbors but chosen you for a slow death so that you will stand for some years as a snag. If only your slow death would give you time to share your riches, your carbon and nutrients through the mycelial connection in your roots that bounds you with your fellows. However, the girdling of your trunk has stopped the flow. Maybe it is all my own projection, but the sap encrusting your trunk feels like tears.

And yes, somehow, I know that in your own way, you feel. Indigenous peoples have always known what the western science denied until recently. It is easier to cut you down without realizing that along with the fungal symbionts entwined in your roots, you sense, hear, touch, perhaps even see. But now your veins have been severed, sensations from limb can no longer reach your roots, nor can your roots communicate with your limbs.

Even if I don’t have an alternative to offer as to how you are being treated, I think it is important to recognize the violence of the severing of connections. I want to offer thanks, my sincere gratitude, for all that you have and will endure as you continue to serve your community, as you remain standing, first shedding your needles, your small branches, and then your larger limbs all the while providing homes for birds and small mammals, a storage place for pine nuts, and more. Even when you fall, other animals or reptiles will find shelter. Your log will hold more moisture, gradually composting and eventually returning nutrients to the soil. So yes, taking the long view, your relationship to your surroundings will remain intact.

Yet, in this moment, the girdle that contorts your body, that constricts you, feels like a taut blindfold emblematic of the mindlessness wrought by settler colonialism that has allowed indiscriminate rupturing of connections, the mindlessness that allows for the continuous extraction of riches, the mindlessness that assumes that the forest would always continue giving without humanity offering anything in return, and the mindlessness of indiscriminate dumping of the leftovers without ever stopping to think about where they are going—the consequences to the air, the water, and the climate.

Dear Tree, the pain of your girdle haunts me. Thank you tree for providing me a space to feel into that pain, that aching grief, and touch the vulnerability of my tender heart.

II. APRIL 25, 2022

Dear Tree,

I am grateful to visit you again. How are you doing? Your green foliage looks fully alive. I’ve now learned that despite the freshness of your wound you were not girdled recently, but last November! The small backhoe I saw on my last visit was there for trail maintenance. Thinning of the forest was completed last year. The processes of life and death are so much slower in trees.

Walking this trail, I realize how much work the foresters have done. They are creating clumps of trees interspersed with small meadows to recreate the look inscribed in the photographs taken by early settlers. We counted the rings on one of the stumps. The tree was 112 or 113 years old. By human terms a good lifetime, for a Ponderosa pine quite short. Many of the stumps were of a similar size, some a bit smaller.

At the turn of the last century, in 1900, likely shortly before your birth, the population of Boulder was only 6,000 people. Now the population has grown by almost 100,000. You must have witnessed such rapid change during your lifetime. The temperature in Colorado has warmed by 2.5 degrees in the last fifty years. Correspondingly, soil moisture has decreased. Maybe it is merciful that you are dying when you are.

Dear Tree, I brought a friend today. We veered off the main trail, to sit in meditation, sharing compassion with the trees that burned in the NCAR fire. The periphery of the burn area was very much coming back to life, the black ashes covered by a carpet of green. Moving inward, the fire burned hotter, singeing the needles of most of the pines, although some still had greenery on their uppermost branches. We sat in the charnel ground, a very rocky area of steep slopes, where the trees were never thinned and the fire reached their crowns, reducing them to black skeletons. Foresters suggest that this fire was very much like a controlled burn or the fires, whether natural or human-made, that occurred before the arrival of the European settlers.

We came to the charnel ground to relate with death, to relate with fire as an integral part of the forest life cycle. We sat in the blackness, each on a rock exposed by the fire, next to a small weeping tree, its sap dripping down the charred bark. To the left, two tall trees–skeletons of trunk and branches, still had so much presence. Many of these trees will be standing for a decade or more, attracting insects and providing valuable habitat as snags. Time moves very slowly for trees.

We also came to relate with life, to the permeability of death and life. Throughout our practice we could hear the cascading gobbling of turkeys as well as the piercing cry of an occasional hawk. New life literally unfolded at our feet, the grass emerging as curled ovals–brilliant emerald against the dark ground.

Dear Tree, sitting on steep slopes we had a splendid view of the city of Boulder–houses like boxes tucked among evergreen green and deciduous gray, reservoirs glistening blue, an old power plant rising in the distance. In one moment, the fire felt like the universe’s big NO, mighty and wrathful in its destructiveness. In another moment it felt like a cleansing, an opportunity, or a demand, to start fresh.

Trees, what is fire asking of us? What human habits need to change so that you can live? So that we all can live? What do we need to let go of, to renounce? What will we be forced to let go of? Scientists tell us that there have been more days of extreme fire danger in the first four months of this year than in any previous year. A Boulder forester I spoke with described the relentless stress of fighting five fires during this record-breaking dry April.

Dear Tree, it is not easy to sit with a dying forest. But we recognize that unless we are willing to feel into the suffering, willing to open our hearts, we cannot come into relationship with you. Unless we come into embodied relationship with the forest, unless we can come into sacred relationship with the forest, it will not be possible to offer proper care. We are so grateful to be able to sit with you, even amid the blackness.

III. APRIL 28, 2022

Dear Trees,

I realize that I have been visiting two different trees near each other. I will visit both of you from now on and address you in the plural, instead of focusing on the separateness of individual trees. All of you are likely connected via a mycelial network underground, sharing nutrients and information with each other. Suzanne Simard has demonstrated that trees even share carbon with other species.2

I went back to sit in the burn area again today, to be present again to the stillness of the charred trees, frozen in a single gesture, to be present with the green meadow that has already emerged, and present to the glistening city of Boulder, where the gray trunks are budding in green, pinks and yellows. I sat present to both the beauty and the suffering. Thich Nhat Hahn suggests that we need to wake up to both in order to be a “buddha in action.”3

As I sat in the charnel ground, I sat with the feelings of fear, despair, and anxiety engendered by the blackness—an anxiety that is so much more potent after the Marshall fire. Likely a knowledgeable local companion would have seen some of that fire scar from where I sat. Six months of abnormally wet weather spurring the growth of grasses was followed by six months of dryness and ferocious winds. The fire, burning at the end of December 2021, when often the land would already be covered with snow, was the most destructive in Colorado history, particularly shocking in that unlike other wildfires, such as the Paradise fire in California, it occurred not in the urban/wildland interface, but in suburbia. How do we sit with the knowledge that conflagrations like this are increasingly likely possibilities?

Two Naropa University faculty members took me to their home destroyed by the fire. Almost twenty years of love, of carefully tending to gardens and trees, a lifetime of books and prized possessions, all reduced to ashes. They and their neighbors who were at home left quickly, grabbing scant belongings, not imagining that the fire would reach them. The fire was capricious–burning some neighborhoods, sparing others. While home hardening is certainly important, in a blaze driven by raging winds there is no predictability, everything is subject to chance. How do we live with this tremendous uncertainty?

Yet, as I practiced, I felt tremendous gentleness, surrounded by death but also new spring growth. Fear was held in the nurturing embrace of mother earth. Gradually it felt safe enough to close my eyes and relax into light and the sound of gobbling turkeys. Slowly, my heart cracked open. Gentleness, kindness, compassion, love. It is only through the tenderness of the human heart that we can meet the enormous suffering of the world. It is only through the tenderness of the human heart that meets enormous suffering with both tears and love that we can create a future where all beings may thrive.

IV. MAY 14, 2022

Dear Trees,

It is so good to see you again. Already two weeks have passed since my last visit. I circle around you and offer pumpkin seeds. My friend Emily, who has come with me again, offers bits of tobacco and then moves away as I stand close. May I touch you? May I touch your wound, your girdle? May I stand with you, may we try to breathe together as we have on previous visits?

Oh Tree, I realize that I have reached out to you instinctively. Appalled by the gash around your trunk, the depth of the cut, I wanted to palpably share my presence, my heart. Touch seemed like a more meaningful form of communication than words. But I realize now that although I approached slowly, I never asked permission. I never stopped long enough to fully drop my projections of what you might be feeling, to fully sense into your presence and tune to your energy fields. I reached out not to feel the roughness of your bark, your toughness that protects you from the elements, but to touch your naked interior.

Do I have a right to touch? Are my fingers soft and tender on your yellow flesh or causing further pain, violating a part of your being that was never meant to be touched?

Oh Tree, what habits give me the privilege to touch without asking permission first? I profess to touch in caring concern, but is that how you receive the contact? Is my proclamation of love too facile? How do I build relationship? You stand here, always present. You have no ability to turn away. You cannot run or hide or reach out to touch back.

But yet, you leave an imprint. Your sap is sticky. As I withdraw my hand, my fingers stick together, stained with your sap.

Oh Tree, I cannot know what you feel. But it is important to recognize that you do feel in your own way and sense into the possibilities of what those feelings might be. Is that effort empathy, in the ecological sense? Allow me to indulge in words as I try to comprehend the stickiness of touch. Newton Harrison calls for empathy for the life web. Reiko Goto and Tim Collins write that empathy “involves attention to expressions of life force and engagement with the world.”4 But the common conception of empathy is that one understands or shares the experience and feelings of another. The assertion of the separation implied by an “I” and an “other” in this definition, and the lack of recognition of any differential in power or privilege between two beings seems to replicate the violence that my touch sought to assuage. I gravitate towards compassion as a preferable term that emphasizes not just feeling the pain of another but committing to help relieve that suffering. Furthermore, a Buddhist understanding of compassion loosens the boundaries between self and other, challenging the concept of a solid inseparable self with a recognition that all beings are interconnected, sharing a common luminous awareness. We breathe the same air. We are all constantly exchanging atoms with all other beings; there are elements in each of our bodies that have resided in a multitude of other bodies. Thich Nhat Hanh describes this as interbeing. Boundless compassion is an acknowledgement and appreciation of this interbeing, a willingness to work ceaselessly to relieve suffering and to exchange one’s sense of well-being for the suffering of others.

If only it were so…The dry wind blowing against my face and your trunk serves as a reminder of the changing climate–an outcome of neither empathy nor compassion. My fingertips quiver. Although the lemon yellow of your girdled flesh appeared soft to my eyes, I am now stuck to your hard, impenetrable wood. How can I feel into this solidity?

My investigation is led by my fingers, the haptic—both the physical sense of touch and the ability to feel, to be touched emotionally. But I don’t know how to comprehend the sensations of my fingers stuck together by the sap exuding from your yellow rawness. To turn for a moment to the insights of others who have investigated this path, Kristen Mundt observes, writing for a special issue of the journal The Arrow dedicated to “Healing Social and Ecological Rifts,” that embodied touch becomes “a vehicle by which we become continually undone….Touch loosens our grip on ‘knowing,’ animating a reality always in relation.”5 Of particular importance to her discussion is the concept of hapticality. While Mundt introduces Fred Morton and Stefano Harney’s use of the term6, I find the discussion offered by Tina Campt, who defines hapticality as “the labor of feeling across difference and precarity; the work of feeling implicated or affected in ways that create restorative intimacy,” more compelling.7 I share Campt’s work, which has moved me so deeply, with hesitation, wary of appropriation, as she is writing in the context of the black gaze. However, her work is located within the body of decolonial theory, the very theory that offers profound insights into the workings of settler colonialism, which has given rise to the catastrophic ecological unraveling that binds me to your sticky flesh. I turn to these theories to recognize the exertion involved in forming relationship, the ways that I am implicated in trying to bridge the gap with one whose being is devalued. Campt continues: “I am not you. I cannot feel what you are feeling. But I am accountable to you and your circumstances. This to me is love.8” Yes, a love that demands profound accountability!

Oh Tree, this is all so sticky. I am you, but not you. Your woody flesh is sticky, but inscrutable. Leading with my fingers, investigating the haptic, informs my understanding of empathy and compassion and leads to a love that takes responsibility for one’s position. Thank you. I am so grateful to be able to stand with you today, to have touched you, to have been touched by you, to continue to labor in the uncertainty of our precarious relationship, and to be mindful of the ways in which my fingers may stain whatever I choose to touch next.

V. MAY 19, 2022

Dear Trees,

As I circle your base, dribbling water and a handful of pumpkin seeds as I go, my offerings feel so meager. What can I share to express my gratitude for the privilege of spending time with you, listening and learning from you? May I touch you, gently? I touch first an area of your girdle that appears rather smooth. It’s cool and solid, not very sticky at all. But am I avoiding your sap? I touch again, the hard droplets soften with my touch. I offer my fingers and breathe with you as best I can.

It is time to say goodbye for a while. Tomorrow I’ll make my way back to California. I will miss you. I will miss my visits, walking up the trail, sighting you from a distance as your yellow band comes into view. I will miss you, deeply.

It’s hard to believe that it’s been just over a month since we met. The wound looked so fresh, a bright yellow that beckoned me. Even now your crown looks healthy. Your needles, still green, must be respiring, even if the flow through your trunk is largely cut off at your girdle. I’ve learned that although the foresters cut a band of bark around your trunk through your phloem, perhaps even your xylem, they weren’t able to destroy your circulatory system entirely. You’ve evolved to be resilient to predators. You die slowly because the axial tracheids embedded deep in your core continue to transmit some fluids even when your cambium is removed.

I don’t know when I will visit you again. Somehow, I must find my way back by next summer. Perhaps you will still be alive. Foresters assure me that you will be even more valuable to the community in death, as a snag, luring insects to feed on you, which in turn will provide bounty for others. The foresters tell me that other trees intended to become snags have been treated with herbicides instead of being girdled. Their deaths may be quicker, but at what cost to the forest ecosystem?

I visited the burn area again today and sat with the short weeping tree. Now there are many more trees who are weeping. The trees look completely charred but deep inside there must be sap that was not burnt. It has been almost two months since the fire, but the trees are still bleeding. Tree time.

These burnt trees will still be standing when I return. Naked, without needles, each tree takes a very different form. There is one tree with so many branches, all whorled and twisted as if they were blown towards the south. The branches of another seem to split into two trees near the base. I wonder if the trees whose needles are completely singed save for bits of green at the top will survive, or if they are alive even now. The foresters say they have no chance, that usually Ponderosas will die if they lose only thirty percent of their needles, certainly if they lose more than seventy percent. But after the big fires in California, local residents protested that foresters were much too quick to cut down trees, cutting down anything they said might die within five years. Is not five years of life worth living?

This forest is so loved, loved by the many people who hike these trails, loved by the many foresters that I have spoken with. There is even a special shuttle that comes to the trails along the foothills in the summer so that people don’t have to drive.

The foresters are trying their best to care for you. One forester tends to the cows that are eating the invasive oat grass. Yes, cows in a forest, but only for a short time to eat the grasses shunned by elk and deer, the grasses that were introduced inadvertently at the same time as the cattle. Another is carefully inspecting the areas that have been thinned, to see how the trees are doing, to check on the spread of exotics and to ascertain if the remaining trees are thriving.

Oh Tree, touching your wound, your girdle, has opened so many questions! Is it an assault when some of your fellows are cut down, or is it as an aspect of care? The foresters say that thinning the dense, often even-aged stands of Ponderosas increases the chances of survival for the remaining trees. They acknowledge the mistaken zealous suppression of fires in the last century, which completely ignored indigenous burning practices. They argue that the changing climate, which increases fire risk, makes thinning even more important.

The foresters that I spoke with all recommended reading The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire That Saved America, in order to understand the origins of fire suppression practices and the ten o’clock rule–that any fire that ignited before ten one morning must be put out by ten the next day.9 The “big burn” refers to a horrific series of fires in 1910 that burned over three million acres of Idaho, Montana, and bits of Washington and British Columbia, only five years after the inception of the US Forest Service. In the aftermath, the need to defend against future fires was used as a rationale to double the minuscule budget of the Forest Service.

But this engaging book tells so much more, placing the fire and the creation of the Forest Service in the context of rapacious exploitation of the forest by miners and loggers, a plundering which contributed to the greatest gap between rich and poor up to that time in the history of the United States. After the fire the voraciousness continued; fire prevention became a rationale to preserve timber for the logging industry, the revenues which in turn provide much of the Forest Service’s budget. Why didn’t the foresters focus my attention on this larger problem of the continued pillaging of the forest and lack of respect for its intrinsic value?

Oh Trees, even Teddy Roosevelt, whose efforts were so central to conservationists’ efforts, spoke of the forest in terms of human benefit. However, true care must de-center the human perspective of forest as resource and focus on your wellbeing, on the wellbeing of the entire interconnected life web.

If humans are to cut down living beings, we must acknowledge what we’re doing. Acknowledging your loss by expressing gratitude, singing your praises, making offerings before felling you begins to rebuild relationship with you, and by extension between humans and the entire life web. It is in this spirit that we have come to sit with you, to begin to listen, to learn, to invoke the spirits and ancestors, and to share our compassionate hearts.

Oh Tree, the foresters working for the city of Boulder are not engaged in commercial logging. They select individual trees for thinning with great care. However, they consistently describe trying to return the forest to conditions that existed before the massive arrival of settlers just over 150 years ago. Yet they know that given the ecological changes caused by the heat of industrialization and the growth and movement of human populations and all that we’ve carried with us and discarded as we’ve moved around the globe, fully restoring the forest to conditions of the past is not possible. We must face the whole truth, the complex challenges of care, that care for the forest means addressing the climate crisis, the consumption crisis, the pollution crises, the social justice crises and so much more if we are to be fully “accountable to you and your circumstances.”

Separated from the wisdom of the life web, these challenges are overwhelming. At the beginning of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, she suggests that “our relationship with land cannot heal until we hear its stories,” until we again look to “other species for guidance.”10 Oh Tree, I share this account of my visits with you as a modest attempt to begin to hear your story.

I am returning home, but not turning away. Thich Nhat Hanh reminds us that, “If you see suffering in the world, but haven’t changed your way of living yet, it means that the awakening isn’t strong enough.”11 Dear Tree, I will carry all that I have experienced, all of these sticky questions, as I continue to feel into what it means to touch and have been touched by you.

ENDNOTES

- Thanks to the Arapahoe, Cheyenne and Ute, the traditional guardians of the unceded territory on which I walked, the Frederick P. Lenz Residential Fellowship in Buddhism and American Culture and Values for support of this project, and to Emily Takahashi for accompanying me and practicing together, to Naropa University faculty members Jane Bunin, Sherry Ellms, Peter Grossenbacher, Anne Parker, and many foresters of the city of Boulder for their informative conversations.

- Suzanne Simard, Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest (New York: Random House, 2021).

- Thich Nhat Hanh, Zen and the Art of Saving the Planet (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2021.), p. 11.

- Tim Collins and Reiko Goto, “The Caledonian Decoy: The Center for Nature in Cities,” (Glasgow, Scotland: Collins and Goto Studio, 2017), p. 8.

- Kristen Mundt, “Touch as Passage: Inhabiting the Colonial Wound,” The Arrow: A Journal of Wakeful Society, Culture and Politics Healing Social and Ecological Rifts Part 2, 8, no. 2, (Fall 2021), p.112.

- See Kristin Mundt, p 29. Original citation from Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study (Brooklyn: Minor Compositions, 2013), p 1.

- Tina M. Campt, A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2021), p. 104.

- Tina M. Campt in “Sanctuary Shorts III – Enclosure: Geographies of Refusal,” https://vimeo.com/641296845, 2021.

- Timothy Egan, The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire That Saved America (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2009).

- Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013).

- Thich Nhat Hanh, p. 11.

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 13, THE ART OF EMPATHY

Published November 2022