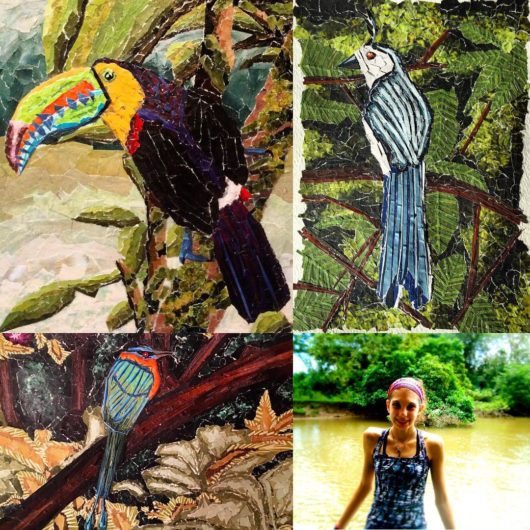

RIIIIIP. Out comes a page from an old issue of Runner’s World, leaving nothing behind but a jagged line along the magazine’s inner fold. I smile: the pure blue sky hanging above the runner is just the shade I need for the feathers on the white-throated magpie-jay coming to life on the heavy sheet of paper before me.

WHITE-THROATED MAGPIE JAY, third piece in “Birds of Costa Rica’ trio, February 2016.

Working in collage brings me peace and satisfaction I haven’t been able to find in working with clay, charcoal, pencil, or paint. Finding just the right shades of paper and placing them in just the right way gives me a puzzle to solve. It occupies my mind and makes me think about the place of things in the world, of my place in the world.

While all my life I’ve been an artist, only in 2010 did I find my true art: collage. Since then, I have created dozens of collages—bits of torn and cut magazines or cardstock held in place with glue. And it’s changed my life.

When I found collage I was 17, mentally precocious yet emotionally precarious, just starting my senior year of high school. About a year earlier, I had accidentally uncovered a family secret. Nothing too out of the ordinary, just garden-variety infidelity in a lower-middle-class suburban family.

My mother and father clashed constantly—brief but loud and angry fights. Our rental home, an impermanent and impersonal place, didn’t lend any stability to the situation. The secret deepened the widening chasm between my once-close father and I, rapidly pushing us farther and farther apart.

In addition to my family’s instability, a mysterious malady was wracking my body. Doctors weren’t sure why I was dropping weight so rapidly, why my bones were weakening, why bruise-like splotches were developing on my shins. I was tired a lot. Everything ached. Looking back, it’s astonishing I was able to compete in cross-country and track—much less function somewhat normally from day to day.

I was hurting, psychologically and physically. I felt trapped in a situation I didn’t want to be in, trapped in a body that was failing me.

It was a broken time.

After school, after practice, I worked on my AP Art portfolio. The AP board required students to create a twelve-piece ‘concentration’ of works that are related in medium and topic. My art teacher encouraged my classmates and me to think about our portfolios over the summer. I was still unsure of what medium I’d use, though the topic I selected was close to my heart: wildlife rehabilitation.

That summer I had started working as a clinic assistant at a local wildlife hospital. Spending my days caring for hawks, turtles, and opossums helped me forget what was going wrong in my life. In fact, I spent the majority of my time at work helping broken creatures recover so that they could one day return to the wild. I looked at my ‘patients’ and hoped that, one day, I too would be set free, that my sick body and shattered family would be made whole again.

Erica Cirino, left, at age 17, releasing an American robin with wildlife rehabilitation volunteers.

Thanks to the honors classes and APs I took as a sophomore and junior, my senior-year schedule was laughably light: two free periods to start the day, AP art, fourth-period lunch, pre-calc, economics, physics, physics lab-alternating-with-gym, and no last period. I didn’t have to come to school until about 9:15 a.m. and, when I didn’t have practice after school, could leave around 1:45 p.m. High school felt less like an academic endeavor and more like day camp—something to keep me out of trouble and to get me out of the house.

Yet all of the free time in my schedule left a lot of room for reflection—sometimes too much room. To calm my mind, during my lunch period, I’d usually jog to the nature preserve across the street from the high school and go hiking. I’d bring my camera and a notebook, snapping shots of the landscape and its flora and fauna and scribbling down my thoughts. Often I was late for math—but so were my classmates. All but the most serious students seemed to be stricken with a severe case of senioritis.

It was on one of my hikes that I arrived at a suitable medium for my concentration. It was probably the second or third day of school, a hazy day in early September, and I wasn’t feeling particularly good. My parents had fought that morning before I left for school. I remember contemplating packing my stuff and my puppy into my Nissan and not coming back home, then realizing my parents would probably find a way to stop me. Resigned, I drove to school earlier than usual, just to escape them.

Once in the safety of the preserve, tired and dizzy, I lay down in some tall wild grasses and flowers, not worrying about ticks or spiders or other things that may bite. I let the brush swallow me: the towering green and gold reedy plants camouflaged my body, gathered it in—adopted it as part of the landscape.

I looked up. Tall grasses chopped up the sky into narrow panels. But between the blades and reeds I could see the piercingly blue sky, which supported both the burning sun and a nearly full moon. Two dichotomous parts of the solar system, representing day and night. They were close together, overlapping, almost as if pasted one on top of another. Slowly crawling clouds added another layer to this sky-collage.

I extended my arm and felt around for my camera. I pulled it to my face and clicked once. Then I placed it back down, nestled deeper into the brush, and closed my eyes.

When I arrived home after practice that evening, I was still thinking about the sky. Cross-legged on my bedroom floor, dressed in my usual track tee shirt and sweatpants, I pulled my camera from my book bag and queued up the photo gallery.

I was surprised to discover that the black-and-white setting on my camera had been flicked on when the photo was taken. Gone was the blue sky and golden haze I had seen. What existed were pieces of black and white, held in place by various shades of gray. It was the epitome of a collage: a juxtaposition of shapes and shades, parts making up a whole.

SKY COLLAGE. Black and white photography. September 2009.

I felt as if the sky was a mirror, revealing to me the smashed bits of my life, yet reassuring me that despite being broken, my life could still be whole—as is nature, with all its disparate parts and pieces fitting together into one world, one Earth. This is when it hit me: collage.

The next morning when I arrived in art class, I pulled a stack of magazines from the bin my teacher kept in the closet. I ripped out pages, carefully organizing each by color. There were piles of blues, browns, reds, oranges and whites. Using a pencil, I sketched the first piece for my portfolio collection on a thick sheet of white paper: the face of a wild hawk, frozen in a fierce scream.

Color by color, I tore up the magazine pages and pasted them over my sketch. I worked through lunch, then math, then economics, then physics, until my piece was finished. My art teacher didn’t kick me out. She didn’t tell me to go to class. She understood: I needed to finish what I had started. I needed to put all the pieces together before I could move on.

RED-TAILED HAWK 1, first piece in ‘Red-tailed Hawk in Rehabilitation’ series. October 2009.

From that first piece, eleven others were born. Together the twelve works tell the story of a wild hawk’s illness, rehabilitation, return to health, and eventual release. I learned more about coping with what is broken while working on these twelve pieces in that one year of high school than I had in my previous 17 years in existence.

Three years later, in my junior year of college, one environmental course required Terry Tempest Williams‘s 2008 book Finding Beauty in a Broken World. In it, Williams describes the human impulse to reunite pieces of things that have fallen apart.

Early in the book Williams attends a mosaic-making workshop in Italy where she learns ‘a mosaic is a conversation between what is broken.’ This is how I feel about my paper collages. How can I make bits of paper torn from different parts of the same page or even completely different pages fit together to create a whole?

Besides mosaics, Williams explores the themes of broken animals, a broken environment, a broken family, broken health, and broken self. It resonated—and still resonates—a lot. Her words bring me peace: “Dignity is a presence, a suffering withheld, a reserve and a patience learned through difficulty, a broken heart held together through acceptance, not bitterness.”

Today I am a 23-year-old full-time freelance writer. I tell stories about the environment and its creatures, about what broken parts make up the whole of the Earth.

Today my family remains divided. My health has improved but is still a little uncertain. Doctors haven’t been able to tell me exactly what went wrong in high school—maybe stress-related, they’ve said.

Today all of this is ok.

Today I move forward, picking up the pieces of my life and trying to fit them together as best I can.