In This Issue

-

Margaret Shiu and Wu Mali ● Plum Tree Creek Action

-

Trena Noval and Lalitha Shankar ● 3rd Space Lab Collective

-

Aviva Rahmani ● Communities of Resistance

-

Loraine Leeson ● Groundswell On the Thames

-

Robin Lasser, Barbara Boissevain, Judith Leinen and Danielle Siembieda ● Refuse Refuge

-

Michele Guieu ● Arts Integration in Elementary Schools

-

Linda Weintraub ● The Fall and Rise of Community

-

Larissa Marangoni ● A Visionary In Rural Ecuador

-

Susan Leibovitz Steinman ● Cultivating Community

-

Lynne Hull ● Madreagua Colombia Project

Fall/Rise Community

INTRODUCTION

RECORDED HISTORY IS TYPICALLY charted through the deeds of great individuals. Complex narratives of conquests, revolutions, discoveries, and accomplishments are encapsulated in the biographies of such prominent personages as Attila the Hun, Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Abraham Lincoln, Dante, Leonardo, Goethe, Ben Franklin, Pablo Picasso, Florence Nightingale, Genghis Kahn, and so forth.

Although exceptional individuals dominate humanity’s historic annals, ‘individualism’ is a modern concept that is largely absent from ancient and medieval civilizations. Tribe is the prevailing social unit. Tribal societies are organized as communities, bound by kinship relations, reciprocal exchange, and geographic roots. Asserting one’s independence and uniqueness, as opposed to contributing to the common good or the collective interests, was introduced as a social construct in the early nineteenth century. Alexis De Tocqueville (1805-1859), the French political historian, noted, ‘Our fathers did not have the word ‘individualism’, which we have coined for our own use, because in their time there was indeed no individual who did not belong to a group and who could be considered as absolutely alone.’1 Allegiance to the concept of individualism is not entrenched in human consciousness.

RISE of INDIVIDUALISM / FALL of COMMUNITY

IT WASN’T UNTIL THE Enlightenment that individual reason, the pursuit of individual interests, and the promotion of individual rights came into being. Furthermore, its appearance was not a triumphant victory over subservience. At the time, individualism was harshly criticized by many, like Joseph-Marie de Maistre (1753 – 1821), a French philosopher and diplomat. Maistre feared that the commonwealth would ‘crumble away, be disconnected into the dust and powder of individuality.’2 To him, and to virtually all conservatives in the early nineteenth century, it was the well-being of society that mattered, not the well-being of the individual. Appeals to the rights of the individual were condemned as leading to political anarchy, the erosion of empathy, the stifling of altruism, economic exploitation, and the withdrawal of citizens from public life. Individualism, they believed, would fracture society.

It wasn’t until individualism migrated to America in the late nineteenth century that freedom, autonomy, and privacy became revered. This updated version of ‘individualism’ was heralded as a means to overcome the ills long associated with Old World socialism, monarchy, and communism. In the progressive view, independence, personal ambition, and unfettered opportunity defined a new, American ideal. The artists of the Hudson River School manifested New World confidence. Thomas Cole, for example, was one of the first American artists to visualize this attitude by portraying the individual standing alone within the grandeur of the wilderness.

The principles of individualism were bolstered in the 20th century by despair regarding the horrific brutality of World War II. Intellectuals blamed the era’s barbarism on the inability of social organizations to uphold peace and provide security. Governmental organizations had failed to secure peace; religious organizations failed to prevent atrocities; judicial organizations failed to uphold justice; educational organizations failed to cultivate wisdom; social organizations failed to preserve humanitarian values. Because of this colossal breakdown of organizations, providing for one’s self became a necessity. Individualism became associated with isolation, not independence. It evoked solitude, not liberty.

Post-war individualism is embodied in Abstract Expressionist painting. Like existential heroes confronting the vast void, abstract expressionists stood alone and unsupported before blank canvases. Individualism in the post War era ceased to be a product of joyful autonomy and unbridled optimism. Instead, it emerged out of desperation and it required courage. Abstract Expressionists triumphed over their era’s angst by relinquishing the hallowed traditions of art and exulting in their individual sensibilities.

As memories of the war faded, they were replaced by euphoria regarding economic prosperity. Individualism that was manifested by Abstract Expressionists as an inspired creative act was usurped by a new kind of individualism that was associated with consumer society. Now ‘individualism’ meant asserting the ‘self’ by conducting the banal act of selecting from a plethora of mass-produced enticements. Necessities, information, and amenities coalesced to serve mass audiences. Individuality faded and was replaced by market categories: suburban middle class, small business owner, retiring baby boomer, etc.

Within the inviolable values of contemporary economic and political systems, personal rights are asserted and private property is amassed. However, resources are not shared and the common good is not privileged. Ironically, this economic system runs on interdependencies. Relationships are even formalized through contracts, alliances, treaties, installment payments, product guarantees, and trading partnerships. But does the market economy resurrect humanity’s age-old predilection for community? The answer is ‘no’. Relationships between consumers and producers lack kinship, devotion, and constancy, the three defining qualities of community. ‘Cooperation’, not ‘community, is the prevailing operational model for contemporary cultures worldwide.

RISE of COMMUNITY / FALL of INDIVIDUALISM

CURRENTLY, A GROWING LEGION of environmentalists and ecologists are reclaiming the concept of community, replete with the age-ole pursuit of affinities and empathies. Environmentalists protest the planetary ravages that result when the actions of entire populaces are ruled by self-interest. Ecologists provide the scientific authority and irrefutable evidence to support their distress over offenses that have become an entrenched norm. Gradually, new cultural values are being nurtured into existence in which the primary unit of consideration is not the self, but the community of humans co-inhabiting the planet with manifold non-human neighbors.

ECO ART: The RISE of ‘WE’ / The FALL of ‘I’

CURRENTLY, INDIVIDUALISM IS being challenged by many environmentalists who correlate self-motivation, self-interest, and self-expression with the beleaguered condition of the planet. They elevate communalism, interdependency, and interrelationships, essentially shrinking the first person singular to a lower case ‘i’, and capitalizing the significance of ‘Us’.

In the English language, the solitary ‘I’ is honored with a capital letter. Graphically, it rises above ‘we’ and ‘us’ and ‘them’, affirming the cultural fixation on individuality. Capitalized words, like capital cities, capital ideas, and capital punishment are associated with importance.3 The fact that ‘I’ was not always been capitalized in the English language provides an indicator of the concept’s evolution over time. Significantly, ‘I’ became capitalized when capitalism emerged, and when Britain and the United States ascended into world powers in the 18th and 19th centuries. The following examples reveal how eco artists are suppressing individualism and cultivating community.

Bright Ugochukwu Eke, a Nigerian eco artist, protests capitalism’s endorsement of private investments, private property, and private profits. He formalized the shift in the status of ‘I’ by posing three questions that appeared in print in the following manner: ‘Who am i? Who is the Other? Where is the meeting point?’4

Eke conveys this principle by involving communities in the collection and construction of his large-scale installations. ‘Ripples and Storm’, for example, was created with thousands of littered water bottles that were collected by students at Skidmore College. Together they explored the metaphoric meanings associated with water. He explains, ‘Water is a universal medium. It’s common to everybody, no matter who or where you are. Whatever I do with water is what every other person does with it in every part of the world. The most interesting part is that we are bound or connected by [water]”.

He then notes, “having perceived this interconnectedness and interdependence of humans and nature, and having felt the damage, the separateness, and barriers we have created selfishly and egoistically, I thought it pertinent to find ways through which we could ameliorate or proffer some solutions to some of these .’5

Capitalizing the word ‘other’ directs attention away from the personal comforts and conveniences generated by these systems for some, and toward the stresses and hazards they engender. He comments, ‘It is high time we changed our notion of ‘Modernist individual freedom’, which only meant freedom from community, freedom from obligation to the world, and freedom from relatedness.’6

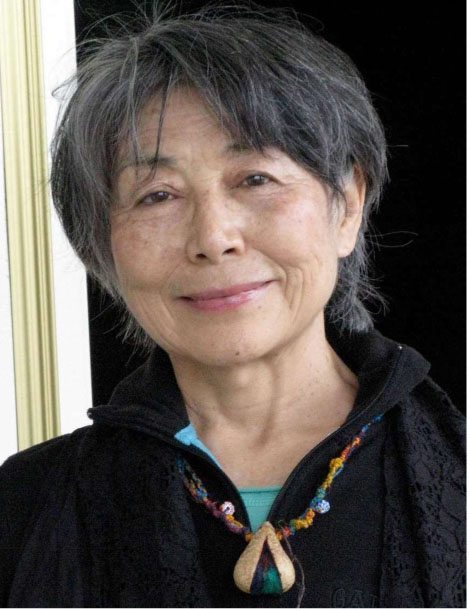

Lily Yeh traveled from North Philadelphia where she lived to Africa to revitalize a village of survivors from the brutal Rwanda massacre that occurred in 1994. A decade had passed, but the people’s psychic wounds had not begun to heal. They were despondent. They lived in squalor. Yeh’s original plan involved constructing a Genocide Memorial Monument to the murdered victims, with their surviving relatives to help them relegate their horrific experiences to history and resume fulfilling lives. The memorial served its purpose, but Yeh remained to integrate full restoration of the village in her ‘Rwanda Healing Project’. Communal values abound in all aspects of this ambitious art project:

- Building new latrine systems and teaching these skills to community members.

- Installing rain water harvest systems as a community project.

- Decorating the bleak houses in the village with mosaics designed by village children.

- Establishing a basket weaving cooperative for elderly women.

- Teaching villagers to construct photo voltaic cells with materials that could be acquired in local markets

- Establishing a micro-lending program to help villagers initiate self-employment

Yeh explains, ‘I realized that the work I have been doing is not only about an individual artist working with disfranchised people in an isolated situation. It is a part of the global movement to make the world a better place through grassroots efforts. Government, professionals and the private sector can build powerful systems such as transportation, utilities, communication and other infrastructure. They can construct physical buildings, highways, and technology complexes. But they cannot solve all the problems caused by the enormous growth of urban centers all over the world, particularly problems caused by poverty and population displacement. We need to focus on building compassionate communities where people have a strong relationship with each other and are genuinely concerned for the welfare of all. Art and culture can function as powerful tools to connect people, strengthen family ties, preserve cultural heritage and build community.'[7]

Yeh’s integratation of art, health, community, and economic development have helped revitalize the old town in Accra, Ghana; the trash-filled land outside of Nairobi in Kenya; and remote villages in Ecuador, China, Ivory Coast and the Republic of Georgia.

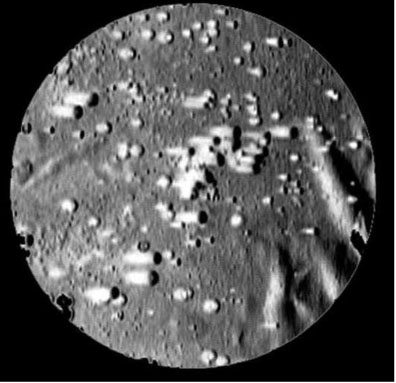

Terika Haapoja, a Finnish eco artist, replaced ego-centric interactions between humans and non-humans with eco-centric interactions that involved non-human species. Haapoja assigned capital importance to the ‘other’ when she created a single channel video projection entitled ‘Succession’ (2008). The video features trillions of invisible bacteria and parasites reproducing and struggling to stay alive.

This life/death drama cannot be viewed by humans with disengagement because these bacteria depend on human bodies for warmth, nourishment, and shelter. The bacteria in this artwork were harvested from the artist’s own body by rubbing her face with a canvas. She then recorded their actions and projected them as a huge glowing disc where they cast doubt on human perceptions of their individuality. ‘Succession’ demonstrates that the ‘self’ consists of vast communities of species that are not even human. Existence means co-existence. Haapoja comments, ‘This work can be considered a portrait because bacteria are part of us. It is called ‘Succession’ because that is the word used by microbiologists to describe the cultivation of microbes. This work shows different colonies of bacteria emerging. They grow and fade. We are not individuals, but communities of species.’8

Just as individualism was ordained by the Enlightenment and by conditions following World War II, conscious participation in community seems ordained today by the dire consequence of humanity’s rampant exploitation of the planet. Likewise, just as Thomas Cole and the Abstract Expressionists reflected the imperative of their era through self-expression, today’s eco artists are embodying the current era by engaging with the ‘commons’. They are asserting that the pedestal that elevated individualism has become precarious due, largely, to the long neglect of ‘communalism’. By recalibrating ‘self’ to include geological/botanical/molecular/ biological/aquatic/atmospheric phenomena, their works attest to the truth that there is no ‘mine’ or ‘yours’. There is only ‘ours’.

END NOTES

1Alexis De Tocquevilee, L’ancien régime et la révolution, 1856, Book II, Ch. II).

2 Joseph-Marie de Maistre, Reflections on the Revolution in France, 1790.

3Winter, Caroline, ‘Me, Myself, and I, New York Times, August 3, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/03/magazine/03wwln-guestsafire-t.html?_r=2&partner=rssuserland&emc=rss&pagewanted=all&oref=slogin&

4 Bright Ugochukwu Eke, Artist’s statement, (October 29, 2008), http://u-bright.blogspot.com/search?updated-max=2008-12-08T08%3A43%3A00-08%3A00&max-results=7.

5 Bright Ugochukwu Eke http://www.environmentandsociety.org/mml/bright-ugochukwu-eke-imo-nigeria

6 Bright Ugochukwu Eke, Artist’s statement, (October 29, 2008), http://u-bright.blogspot.com/search?updated-max=2008-12-08T08%3A43%3A00-08%3A00&max-results=7.

7Lily Yeh quoted in ‘Warrior Angel: The Work of Lily Yeh’ October 21, 2004. Bill Moskin and Jill Jackson, page 8.

8Terike Haapoja, Interview, July 13, 2010. This definition of ‘succession’ differs from that used by ecologists which refers to the reoccupation of a piece of land after a severe disturbance – a lava flow, landslide, fire, logging, etc. An orderly succession of life forms takes place as each prepares the habitat for the next occupants.