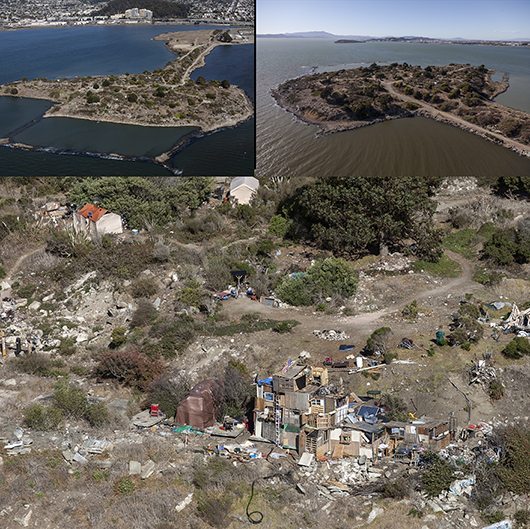

Location: Albany, California

NOTE ABOUT THE TEXTS

The following texts on the Refuge in Refuse project by the BRIDJE Club reflect the authors’ diverse points of view, creating shared and eclectic experiences while working on this project. The project in whole is a transmedia telling of the stories of the experiences at the Albany Bulb through multiple points of view. The voice of the BRIDJE Club in this project is not harmonious, but rather pushed, pulled, and stretched in the direction of the individual authors.Four authors shape this article. Robin Lasser provides an overview of the people, art, and ecology of the landfill. Barbara Boissevain addresses the relationships between human justice and environmental issues. Danielle Siembieda writes about technology and its connections to the landfill community. Judith Leinen looks at urban planning and considers the multiple realities that exist simultaneously at the Albany Landfill.

In this work we are honored to highlight several of the residents. There are over 60 residents we could introduce if given the space. We would need volumes to do real justice to this extraordinary place and the individuals who have made this landfill not only their home, but a significant destination point brimming with vitality, culture, and spirit.

HUDDLED INSIDE THEIR LANDFILL MANSION, Boxer Bob, Danielle Evans, and I talk about Danielle’s paintings. Shivering, the three of us step out of the big house onto the moist cliff overlooking the bay. The black tarp roof billows rhythmically in the late afternoon gust. Bob insists the house is breathing. He leaps onto the roof boxing with the wind, giving it his best punch, over and over again.

Boxer Bob and Danielle live at the Albany Bulb Landfill in the San Francisco Bay Area. They moved to this decommissioned construction dump two years ago. Bob obsessively builds his three-story pallet mansion to abate his fear of being homeless. Danielle paints to imagine the world she desires and to keep herself sane.

I. POLITICS

MORE THAN 60 FRIENDLY CAMPERS live in this community with world-class views and significant art and architecture. The residents are all slated for immediate eviction. The landfill is changing hands from the city of Albany to the California State Park system, but as one camper, Mom-a-Bear, eloquently declared at a recent Albany City Council meeting, ‘We already have a world-class park—no need to make a new one.’

II. LANDFILL HISTORY

MANDALA—GRIM SALUTES THE SUNRISE standing in the rusting rubble located near the Landfill Library. Photo © Robin Lasser + Judith Leinen

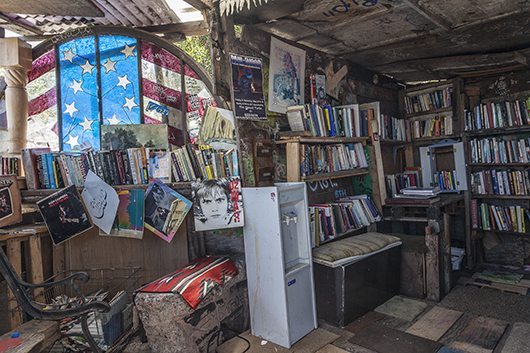

THE MUDFLATS THAT FORM THE BASE OF THE LANDFILL migrated from the Sierra Nevada, residue from the gold rush when hydraulic gold mining unleashed sediment from rivers for delivery to the San Francisco Bay. In 1963, on top of dreams of gold, a construction dump was born and a human-made spit of land took shape, supporting rebar and cement slabs along with marble from Richmond’s demolished City Hall and the city of Berkeley’s former library. Today the Landfill Library, created by Jimbow-the-Hobow, resides on the northeast side of the Albany Landfill. You can check out the book of your choice, utilizing the honor system for return. One filmmaker called this place ‘Bums’ Paradise.’ I have grown to think of it as home away from home.

THE LANDFILL LIBRARY, created by Jimbow-the-Hobow, allows bulb residents to check out any book on the honor system. Photo © Robin Lasser

STANDING ON THE MANSION ROOF ONE CAN SEE THE GOLDEN GATE BRIDGE directly to the west, the port of Oakland to the south, Richmond oil refineries due north, and Albany due east. Photo © Robin Lasser + Barbara Boissevain

III. OUTSIDER/INSIDER

THE ALBANY BULB, FOR ME, is one of the last stands in America where creative anarchy rules and by that I mean the plants are wild, the art dotting every square inch of the peninsula is unsanctioned, and the residents embrace an alternative lifestyle. These elements seem to be in harmony with one and other; it seems to be working.

I am an artist, a “dog walker,” a ‘housey’ (what the Bulb residents call people who have permanent homes)—and a kindred spirit roaming the Bulb for almost two decades. I think this former dump is the jewel of Albany, a vital destination point. The upcoming eviction will be a great loss not only to the 60 or more residents who call this landfill their home, but to all of us who feel it is important to explore untamed territory, the boundaries between public and private space, and the intersection of people, art and ecology.

Tee Pee (top left); Landfill Kitchen,(bottom left); Mom-a-Bear’s tent with plastic altar landscaping (top right); and Lewanda’s campsite with clock tree + candy cane/grocery cart gate (bottom right). Photos © Robin Lasser

How can I consider myself an environmentalist if I don’t also take into consideration human justice?

I began filming at the Albany Bulb for the purpose of documenting some of the ingenious ways some of the residents create home. I am a professor of art at San Jose State University living in Oakland, California. For the past decade I have created, along with collaborator Adrienne Pao, nomadic wearable architecture that we call “Dress Tents.” Imagine a 15-foot-tall lady wearing a dress that you can walk into and utilize as a tent; a gathering space to consider the geopolitics of people and place. I wanted to explore how residents utilized recycled fabrics in their tent creations. Eventually I began to talk more deeply with some of the residents. What turned the tides for me was something resident Stephanie Ringstad shared about camping at the dump: ‘Living out here is considered homeless although we consider it our home.’ Her message hooked me and I refocused my lens on a fiercely alternative group of people living creatively amongst ruins littered with art, architecture, and wild plants.

IV. AESTHETICS

WHERE DO YOU GO WHEN IT STORMS? Some residents respond with creative actions, utilizing artmaking as a life jacket, a coping mechanism to combat the stress of life on the brink of change. At the landfill, residents create and live their dreams.

I am drawn to the numerous examples of human resilience and creativity found at the Bulb, from the colorful plastic toy altars created by Mom-a-Bear on the Northwest side of her campsite, to the collection of clocks hung on a tree trunk (one is working) in front of the candy cane and grocery cart gate leading up to Lewanda’s homestead, to the imagined green fairies that keep people from sleeping in Mad Mark’s castle, the deep piles of dumpster-dive palates creeping their way into Boxer Bob’s mansion, and the hordes of books filling the landfill library. I have fallen in love with some of the people at the dump, their multiple realities, insistence on free living, and their creative spirit.

How our paths at the landfill have become intertwined, and what we create together, provide context for both this text and an upcoming exhibition at SOMARTS in San Francisco, February 12-March 14, 2015. Some of the landfill residents are contributing artists, as well as subjects in the art exhibition and my feature-length film. We explore the roles of aesthetics within political struggle, issues of human justice at odds with environmental issues, and who has the right to do what in public. The project is a cooperative effort between the collaborating artists/authors contributing to this text and the campers living at the Albany Landfill.

Some of the portraits published in this story take on the form of a mandala. The word mandala is Sanskrit for simple circle. German artist Judith Leinen and I create these mandalas to honor the landfill residents. They are meditations on and celebrations of the myriad ways residents use their creativity in response to life on the brink of change. We work with Grim, Boxer Bob, and Tamara Robinson by asking each resident to act out their dreams and fears. Their performances for the camera are incorporated in the creation of these pieces. The mandalas come alive as zoetropes when spun on discs incorporated into bike-like sculptures made from landfill scraps. The animations on the sculptures reveal actions by residents who in time of crisis choose to live creatively by expressing themselves with architecture, fashion, painting, boxing, performing, and community organizing.

V. CHANGING VOICES

THE FOLLOWING STORY EXCERPTS are direct quotes transcribed from the film I am currently developing. Here my voice ends and the extraordinary voices of Amber Whitson, Grimm (Allan Brandon Mercer), Tamara Robinson, Danielle Evans, Boxer Bob (Bob Anderson), and Mad Mark (Mark Matohnan) begin. These stories are followed by my fellow authors’ reflections.

Yours in the intersection of art, ecology, social justice and everything wild!

—Robin Lasser, Professor of Art, San Jose State University

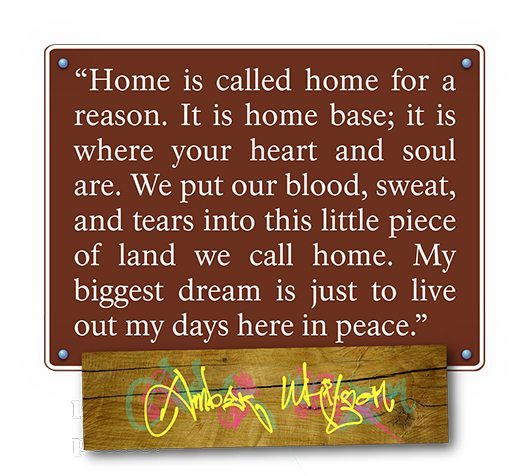

AMBER WHITSON, A SEVEN-YEAR RESIDENT OF THE BULB, is an organizer who works with great dedication to preserve the landfill community. Amber is also one of the narrators for the developing feature length film from which these quotes are born. Photo © Robin Lasser

AMBER WHITSON:

Home is called home for a reason. It is home base; it is where your heart and soul are. We put our blood, sweat, and tears into this little piece of land we call home. My biggest dream is just to live out my days here in peace. I know I have lots of days left, I am only 32 but I don’t think that is so unreasonable especially with all the work I do out here for the community and the amount of persecution I have gone through. They stole my son; they did all kinds of horrible stuff. They jailed me, put me in a mental institution for 24 hours before the doctor wouldn’t keep me there saying, ‘you do not belong here you are not crazy.’

CALIFORNIA STATE PARK SIGNAGE highlighting Amber Whitson’s perspectives. Photo © Robin Lasser and Danielle Siembieda

Now I am forced into getting ready to leave home behind, which is so weird. I don’t know how to be homeless. How do you compact an entire existence into what you can carry with you? You know, once you have an entire existence. Reducing everything to only what you need to survive. I eat so healthy now. Soon I will not be able to have a stove. I don’t even mind eating leftovers from dumpsters, I do it all the time out here, but it is going to be so different when we won’t have anywhere to live. The thought of being tethered to a town sidewalk, rather than our home here, is incomprehensible.

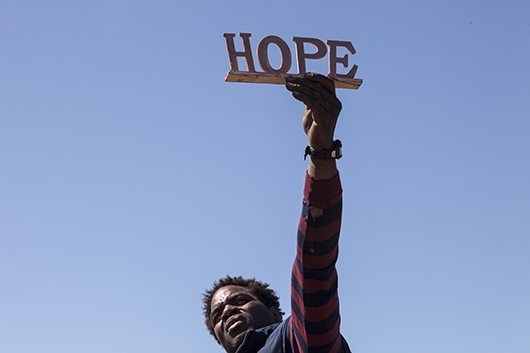

GRIM (ALLAN BRANDON MERCER):

I grew up in South Central L.A. I was the closest thing to white on my block. In 1982 I was breakdancing and in 1983 I was getting broke off. I stayed that way until about 1989 and then I was stealing cars and chasing gangbangers. The cops were chasing me because I was stealing cars, then they stopped trying to capture me and they started shooting at the cars I was stealing. My mom said we should move up to the high desert for her health near our grandma and I said, ‘yes mom, I am allergic to bullets too, let’s go.’

I had a dream once about a guy screaming that I should show him how to live without money, and the only thing he had to offer was tons and tons of cash, which I was laughing off because apparently it wasn’t worth anything but he had no other recourse than to offer me money because he knew nothing else.’

TAMARA ROBINSON FEELS ‘INVISIBLE’ in a culture that disregards her very existence. Photos © Robin Lasser

TAMARA ROBINSON:

I have noticed people out here do more for each other than I have seen anywhere else. This may have just been a dump that nobody wanted but we made it our home.

I am nobody, really. I am just a 23-year-old ex-convict who is dying. I can dream all I want about being the Wicked Witch of the West, Elphaba—she was my favorite because, just like me, she was a person, and the reason why she turned into the Wicked Witch is because of life and its horrors. I don’t even feel alive, just like a spirit roaming. I know I see people and people see me but the way they make me feel by their quick judgment, I wouldn’t say I was alive or anything.

When I was a kid I was kind of thrown out to the wolves. I was running around on the streets at the age of 13, got pregnant, and had a kid. What happened to her? Unfortunately she left. She is not here anymore. That is why I needed the heroine. My boyfriend he would beat me up a lot and sometimes he would use his guns or whatever . he pulled the trigger and guess who got the bullet, not me. Because she was interfering he shot her. And that is when my life ended.

DANIELLE EVANS CREATES BEAUTIFUL PAINTINGS of the life she imagines for herself in her home at the Albany landfill. Photo © Robin Lasser

DANIELLE EVANS:

The paintings are my mood swings. I just go with how I feel and what my mind tells me to do. I paint when I am pissed off. I express my anger in the paintings. I started painting two months after we arrived here. To be honest it is a little crazy living here sometimes. Some of the people around here are kind of nutty so I stay to myself pretty much and I paint.

Following my dreams and getting out my feelings, I think that is what I am doing. It is a good way of meditation, it helps me to relax and to not hurt anybody or think evil thoughts. Painting makes me feel calm and saner. I am able to go to sleep with a relaxed mind, not all jacked up. If I don’t paint I can’t sleep becauseof all the anxiety of what is going on. So, painting is good.

BOXER BOB:

In boxing you are dealing with the fight for perfection, in boxing you deal with the fight of the fittest. Funny as it may seem, this is crazy, but my trainers used to say to me ‘boxing is like having sex’ and I never could understand what they meant by that. What I found out is that you have to put everything you have inside boxing and what comes out of it is the craziest thing, as far as using the body mechanics of love making.

Building, yes that is a fight too. To feel the way that Noah felt when he built the ark, bringing all the wood up here from the dumpster, doing stuff I had never done before, and then actually witnessing myself doing it. My biggest fear is becoming homeless and that great motivation turned into the mansion.

It is crazy, just to have my stuff outside was, oh my god, so embarrassing. I had so much stuff I had to cover it up. I needed a garage, boom, a tool room, boom, and now that we are settled down, oh my god, we are living in a community so we need a church. When you settle in and look out into the view you think, this place deserves a mansion. It is almost like the lifestyles of the rich and famous. When you are homeless you are almost like dead but in this place where I am at now, I can actually feel myself breathing a little bit.

MAD MARK:

I was living on a boat named Griffin. It was shot down, the boat sank and I was forced to live ashore. It was winter and I was not going to be able to get a job in the immediate future so I took on this thing, I began to build the castle. I thought it would be a good place to lock something down; a good place to come and watch the sunset. I thought it was going to be really small and hardly anyone would know about it. I know I wasn’t really thinking about living there. I was building it as a gift to California. For a second there I started to feel really proud of myself. I made a plaque, a dedication that I chiseled out of granite that said ‘To California With A Heart of Gold, Live Up To It And Let The Good Times Roll.’ On the top it read, ‘Fairy Castle 2000 Clear the Air.’

Let me explain the concept behind the castle. Diamonds are forever and your soul is eternal and with heart and soul you till the soil with your spade and if you do that correctly you will be in clover. It is a riddle that documents a numerology blueprint that is 8,000 years old. The reason I built this was because of that document and the golden age of prosperity.

You are only as real as your dreams are. See this net by the window, it went up to heaven, it was the size of a freight truck. It went around and around and caught all these fairies. A whole truckload of them. That is why I call this the Fairy Castle. The green fairies traveled all the way from Ireland. That is why nobody can sleep in the castle.

In 2012 a former resident, Kelly Ray Bouchard, wrote this prophetic white rock manifesto:

This landfill is made from the shattered remnants of buildings and structures that not so long ago were whole and standing, framed in concrete and steel expected and intended to last. Now through the concrete, grasses make their way. Atop the plateau a eucalyptus drives its roots down through the cracks. Waves constantly erode the shoreline and wash out the edge of the road. And here and there, in sections leveled and cleared of rebar, our tents are hidden away. We live around and within the rubble. Live not merely survive. Can you see how hopeful this is?

The Bulb is not utopia. It is not free from strife and cruelty and chaos, but neither is anywhere else. It is flawed but it isn’t broken and shouldn’t be treated that way. We too are flawed but not broken. So when the politicians start asking their questions and making their decisions, you can help ensure that we aren’t treated that way. Enjoy the Bulb. It is yours as much as it is anybody’s or ours.

VI. EPILOGUE

Danielle Evans spoke first:

Bobbie is in his artist denial anger stage. Yesterday he had a nervous breakdown. The ambulance came and everything. He is wandering around now. He had the chills and everything. He scared the crap out of me. I don’t know how to feel today, it is like I am numb. I am really depressed. I feel like I want to hurt someone for doing this to us.

Boxer Bob broke the silence:

They looked at my house and said it had to be torn down because it wasn’t safe for people to walk on like it was going to fall down any minute. It was crazy how the whole side right there, the side that they were worried about, it took them 15 minutes with a bulldozer just to move it. And it wouldn’t even move. Man that is crazy. It was like boxing to me at first. How do you take a punch? They thought the first time he was so weak that he would go down. The first punch didn’t do nothing but tear his shirt off. The critics said, ‘we need to know if the big house won the fight.’ I think it won. I really do.

I’ve been through some heart-breaking things in my boxing career, not knowing that boxing was in my heart. You go through stuff. It was a beautiful house and it will always stay in my heart forever. So you know, the house will never die. I am real sorry that my kids didn’t see it though because it inspired a lot of people; you know they would be inspired by the situation here with the house. I wanted to share that with my kids. I am not going to let this get me down. I’m thinking now, I am going to surprise Danielle with a new boat or tree house.

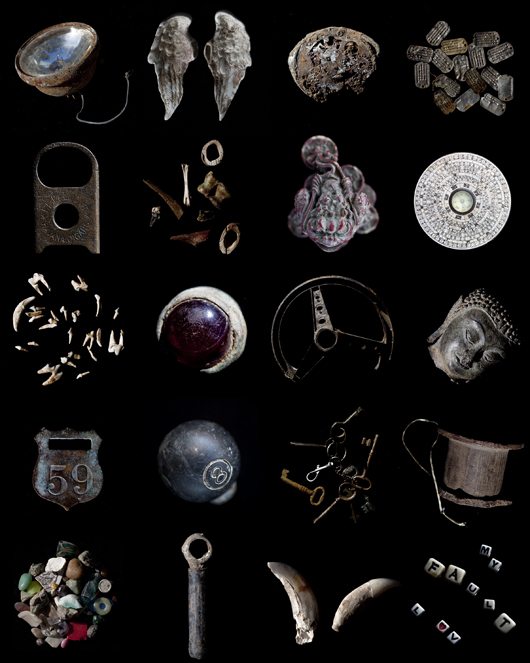

BOXER BOB PULLED THIS OBJECT OUT OF THE MANSION RUBBLE. It was one of the very few things that survived the devastation. Photo © Robin Lasser

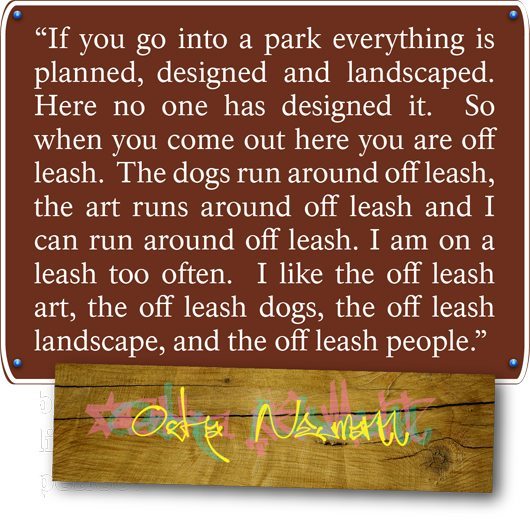

CALIFORNIA STATE PARK SIGNAGE highlighting Osha Neumann’s perspectives. © Robin Lasser and Danielle Siembieda

VII. OUR JOINT HUMANITY IS AT STAKE AT THE ALBANY BULB

How do we protect members of our own species while allowing other species to survive?

THE STORY OF THE ALBANY BULB is an important intersection of social justice and environmental issues. The struggles of the residents to maintain their housing at the Albany Bulb demonstrates the inextricable link between respecting humanity and respecting the environment. Many of the residents of the Bulb have mental and physical disabilities that make it hard for them to find permanent, affordable housing. Here at the Bulb they have created unsanctioned homes as a means of survival. The Bay Area is notorious for the high cost of living and extreme population pressures on its environs. Many different non-human species have been threatened by extinction because of these same forces. Part of the impetus toward preserving the Bulb but evicting the human residents is to create a park where the shoreline is ecologically rehabilitated. The East Bay Regional Park District has approved the Albany Beach Restoration Project, which will result in its conversion as part of McLaughlin Eastshore State Park. Environmentally based organizations such as the Sierra Club have come out in support of the Bulb’s conversion into a park and the removal of the Bulb’s homeless inhabitants.

CALIFORNIA STATE PARK SIGNAGE highlighting Robin Lasser’s perspectives. © Robin Lasser and Danielle Siembieda

The situation has resulted in a standoff between advocates for the homeless and organizations like ‘Save the Bay’ that are interested in protecting and restoring the Bay. Some of the advocates for the conversion into a park are suggesting that the unsanctioned art at the Bulb remain after the current inhabitants are forced to leave. Civil rights lawyer Osha Neumann spoke directly on this issue when he stated the following:

I feel that once this eviction happens the art on the landfill will also be evicted. Frankly I am not all that excited for the art to be preserved in what I am afraid will be left of this place. For me it would be a distressing sign if somehow those who have engineered this eviction, and the state park for whose benefit this eviction is supposedly happening, made a decision that they don’t care about the people. The people can all go but actually we would like to keep this little memento of this period. That kind of sucks. But I do think the art is going to go too.

To me it is a great sadness that this landfill experiment will disappear. The landfill has been a creative and self-sustaining eco system that includes all varieties of people and the dogs and the birds and the trees and the art—and all that is going to go. There are not many places left where you can see how nature reclaimed the rubble of our society. Everything that is there grew on its own and you can see how nature has taken over and restored what we have destroyed. The signs of that experiment are going to go. And the experiment in living is going to go also because we don’t have a safety net for the people who are out there, for people who have nothing. We don’t have anything for them, but here is a place where it doesn’t cost us a dime, where they have actually lived and survived in a way the world is going to have to live—if we are going to prevent the catastrophic destruction of the climate and biosphere that we are working on now because of our over consumption.

—Excerpt from Robin Lasser’s documentary film Refuge in Refuse, 2014.

The Sierra Club has been heavily criticized for their support of the evictions of the people who call the Bulb their home. The mission of the Sierra Club includes ‘the maintenance and protection of the environment for the enjoyment of the people.’ This raises the question whether this is meant for all human beings or only certain people who are considered the ‘right kind’ of people.

Historically, government agencies, policymakers, environmental organizations and even social justice organizations have tended to view environmental justice and social justice as two distinct and sometimes distant sectors. This oppositional view of these two vulnerable parts of our society does not serve to help either. At stake here, in resolving the challenging urban and environmental issues at the Albany Bulb is our joint humanity. Are we a society that can embody values that protect the weakest members of our society without compromising other vital species in our environment in the process?

VIII. THE PARALLEL NEIGHBORHOOD—THERE´S ALWAYS MORE THAN ONE VERSION OF REALITY

THE AESTHETIC QUALITY OF THIS peninsula is hard to grasp as the atmosphere is swinging between extreme polarities. The Albany Bulb’s hermetic system follows its own rules, language, and means of interaction. However, it is easily accessible and open to outsiders. Beauty and unusual shapes, and stunning sculptural and architectural inventions, are visibly merged together with poverty, criminality, and the constant danger of being homeless. Maybe it is this bipolar structure of the Bulb that works as a mediator between two worlds that are simultaneously found there. We perceive daily life situations that do not require too much of our attention, while at the same time the peninsula also gives us a sense of an overwhelming ‘otherness’ that is present to us.

The composition that evolved in the communal living at the Albany Bulb is one we would find in theories about settlements and city development. The structures could be read as representations of community, spirituality, and knowledge. We find these three features, among other characteristics, in literature.1 The center of the town has an agora that is also a crosspoint of the arterial system of small pathways that lead through the peninsula. They connect the inner and peripheral regions of the community, creating a centralized city plan. The only solid construction, made of concrete, is Mad Mark´s castle.2

This spiritual building is solely dedicated to fairies and love. It is not meant to provide a living space for inhabitants. The builder’s decision to pay so much attention and effort to a structure that is not used as a shelter is especially remarkable in a situation of rare housing and seems to be a repetitive pattern in human behavior and the motivation of ‘building’ in general. The most controversial communal building is the library.3 This construction, made from found pieces of different construction materials and supplied with a collection of found and contributed books, has been destroyed and rebuilt over and over again. These devastations and also the motivation for rebuilding come not from any outsider, but by powers coming from within the community.

If the borderline between life and art is straight, clear, and visible, the interaction with it suggests comfort and orientation. At the same time the borderline can lead to a deficiency. Fenced and distanced from regular life, art can suffer from disconnection, become harmless, and lose its impact. If the opposite is the case, and the clear and straight borderline between life and art has been disturbed, no longer leaving a line, but rather a cloud, our confidence can be disturbed as well. Orientation can turn into disorder, and comfortable safety into confusion, but a passive reception can also turn into direct involvement and confrontation. Moments like these are special and energetic in the arts and can evolve, for example, when a situation contains parts of both worlds: profane daily life and the unreal, created invention of art.

Conditions like these are instantly present at the Albany Bulb. A lot of creation onsite initially was not meant to be art but demonstrates the above-mentioned qualities and characteristics originally assigned to art. Regardless of whether we look at situations and atmospheres or at a more materialized and touchable outcome, e.g. the shapes of inventions for daily use—art and life are mixed up and have merged into something new. The borderline that is usually there to help us separate between the two worlds does not exist. Maybe even worse: as soon as we think we got it, we found our orientation, it is very likely that it turns out to be in fact completely different. There are multiple perspectives from which we can look at the phenomenon of the Bulb. The subjective perception supplied with a set of criteria and categories of value can determine the one or the other actuality, as well as additional various possible versions of reality in between these two poles.

The unusual part is that everything is grown out of itself and without a bigger plan or intention. The place seems to be completely natural but completely artificial at the same time. It opens a dialog and functions as a mediator between both nature and artifice, coexisting at the same time. It has the ability to connect both and also to connect a visitor to both. What are the ingredients for a phenomenon like this? To learn and steal from the Bulb, to make parts visible and share these magic moments in the language of artwork is a covered chance that the Bulb keeps. Research into this phenomenon and its recipe could be used as a lens through which we look at practical artmaking and transferred to studio practice. Beyond that, such research could serve as a thinking guide that helps us access and understand art and society on a very general level.

IX. COMMUNITY-LED TECHNOLOGY: HOW CAN WE BUILD IT TO MEAN SOMETHING?

THERE IS A POWER GRID AT Albany Bulb. It may not be mapped out or sanctioned by the utilities but it allows the residents onsite to communicate, mobilize, and connect. Solar, mobile, and open-source technology have enabled the most fundamental human need of gathering. Technology has empowered the residents of the Albany Bulb to live autonomously, yet they desire their reality to be recognized by outside political communities. On the transverse, the overgrowing local tech workers are desperately trying to change their public image by creating Apps and tech tools for the “disempowered” in order to avert the spotlight on the housing crisis in the Bay Area. Perceived realities and conflicts of power are central aspects of the ‘Refuge in Refuse’ project. We are translating the realities of these communities through hyperreality and simulacra through technology such as augmented reality, 3D printing, and digital libraries.

THE ART WILL BE THERE FOREVER, AT LEAST VIRTUALLY: AUGMENTED REALITY AND LAND

AUGMENTED REALITY IS A LIVE direct or indirect view of a physical, real-world environment whose elements are augmented (or supplemented) by computer-generated sensory input such as sound, video, graphics, or GPS data4.This technology allows for a sort of historic marker to remain on site bringing past and present visitors together to commemorate their shared life experiences. Traces of webbed moments are triggered by the nostalgic memories found through augmented reality. Buildings can be torn down, people removed, and waterfront gardens engulfed by rising sea levels but the images of this transient village will remain in its own dimension. A layer of reality seen only through the lens of cybernetic technology will become a destination point for cultural anthropologists of the future, descendants of rthe esidents, and whoever chooses to dig into the layered archive of the Albany Bulb.

We have partnered with F3 Associates, an architectural surveying company, to do 3D scanning of the main structures and residents at the Albany Bulb. Using California Coordinates, a precise form of GPS data, virtual models will be created and made available indefinitely through AR viewing devices, regardless of what is built or destroyed in place of the Bulb. We will also add layers illustrating the fantasies or hyperreality of the residents. For example, using AR one will be able to see Mad Mark’s Castle with the fairies he claims continue to live there. QR Code markers will be placed at the sites where the structures were built for future reference for visitors to the Bulb. The AR development will utilize software from Metaio and be available for viewing on most AR apps including Junaio and Layar.

OPEN DATA AS AN ARCHIVE

THE STORIES OF THE PEOPLE AT THE Albany Bulb will soon become a trace archive—a whisper, a shadow, a ghost of a short point in history. In the spectrum of time we know little about the personalities and visions of most transient people. Through technology we are creating the stage for the stories of the Albany Bulb to be realized in collaboration with the Bulb community and a community of tech workers. By bringing these groups together for a weekend Hackathon (App workshop), these communities can connect, share, and make tools and technology that will share their visions. The stories we have collected will be archived through open technology as an API (application programming interface) library in GitHub (a data collection site).

We have been collecting video, sound, photographs, and 3D scans of the present ecology, architecture, and people of the Albany Bulb. In order to preserve this moment in history we are submitting this content to the California Digital Archive for a legacy archive as well as to GitHub an open database for developers using API. The process of placing our content (i.e. images and videos) is like giving books to a library. The California Digital Library will serve as a long-term open data set that will be managed for centuries for use by academic researchers, journalists, app developers, economists, and anyone else who uses data to tell a story.

The BRIDJE Club is a collective of four artists, Barbara Boissevain, Robin Lasser, Danielle Siembieda and Judith Leinen. As a collective we are committed to representing works of art that address issues around human justice, ecology, and the public space. See www.refugeinrefuse.weebly.com.

END NOTES

1 Examples include Lewis Mumford: ‘The City in History,’ Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., New York, 1961, and Sigfried Gideon: ‘Space,Time and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition,’ Harvard University Press, Cambridge 1941.

2 Mad Mark´s castle resulted in around 4,570,000 hits through a Google search and is also an geographic point in google maps: %3D&ie=UTF-8&ei=WAgxU97KNITwoAS5iIGYCQ&ved=0CAsQ_AUoAw

3 ibid. Mumford: The invention of such forms as the written record, the library, the archive, the school and the university is one of the earliest and most characteristic achievements of the city.

4 Source: Wikipedia.