Location: US/Mexico Border

I. A PERILOUS JOURNEY

IT IS SAID THAT EL PASO, TEXAS, is the safest city in the United States. Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, just two miles away across the border, has the sad reputation of being the most violent city in Latin America. Between these antipodes, the lives of many people are affected by the incessant crossings, legally or illegally, of the US/ Mexico border. The desert of Chihuahua is vast and relentless. It is the protagonist of endless stories that I heard from undocumented unaccompanied minors who dared to cross it, abandoning themselves to the helplessness of inconceivable distance, horizons that melt in the torrid heat, or the freezing cold of winter months. Nothing in the desert is easy or benevolent. Everything is painful and alarming. Many manage to cross. Many more, uncounted for and anonymous, perish in the journey.

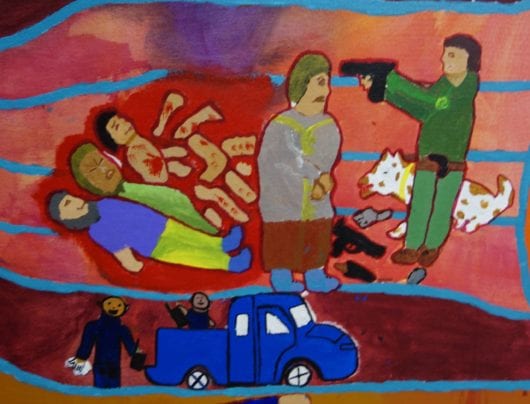

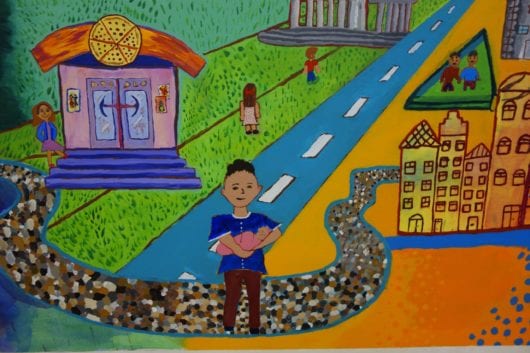

SECOND CHANCES, mural, 2016. Photo: Claudia Bernardi.

But, what alternative did they have?

According to the US Office of Refugee Resettlement, a total of 50,036 unaccompanied undocumented minors were taken into custody after crossing the border in fiscal 2018. Most of the children, 30 % of them younger than twelve years old, were from El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Mexico. They crossed the U.S./ Mexico border alone, or with adults who were not relatives, often fleeing poverty, gangs, corruption cartels, and violence, hoping to seek asylum in the United States. These unaccompanied undocumented minors embark on a perilous journey escaping all forms of abuse and violence linked to poverty, gangs and cartels in their home countries.

When they cross the US/ Mexico border they frequently become victims of human trafficking, and exploitation. Those who manage to cross la frontera have to face the challenges of encountering the border patrol. In 2018, over 66,000 unaccompanied, undocumented, migrant Central American children and youth crossed the United States/ Mexico border. In 2019, an estimated 600 undocumented unsupervised children and youth crossed the border daily.

Since 2015, I have been facilitating community-based and collaborative mural projects with undocumented, unaccompanied, Central American migrant minors detained in maximum-security prisons in the United States. These migrant youth, both female and male, were incarcerated after being detained at the US border. Their crime, it seemed, was to have crossed the border without a passport or the corresponding paperwork. There were more serious allegations identifying that some minors may have engaged in gang and cartel-related violence previous to having been detained by the US Border Patrol. This was, in fact, a severe accusation. Yet, the measures of punishment and castigation seemed disproportionate when the reasons for which the youth had crossed the border were taken into consideration.

One of the recent mural projects Second Chances, acquires a prominent significance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Since April 2020, the Trump administration has been implementing aggressive immigration enforcement by deporting thousands of people to their countries of origin despite the fact that some of them may be sick with the coronavirus or asymptomatic carriers. The incarcerated youth and the recently deported men, women and children chose to leave their families behind, their communities, their language and traditions. They arrived in desperation and eager to survive.

II. SECOND CHANCES

SECOND CHANCES, A 52′ BY 5′ two paneled mural, meticulously depicts the reasons for which undocumented minors opt for their self-imposed exodus from Central America to the United States. This mural embodies the hopes of the incarcerated youth.

My role as the facilitator and project director is exclusively, to ask questions. I do not paint the mural, I do not suggest images or colors, and I do not offer suggestions on how to resolve any given idea.

What is this mural going to be about?

What story do you want to tell in this mural?

Is there a past, present and future in this mural?

If, indeed, there is a timeline, where would you place the past?

To the right? Or to the left?

What about the future, and the present?

To enter a maximum-security facility and interact with incarcerated minor males and females may be perceived as challenging. I was happy to have the support of C.C, Program Manager of the Office of Refugee Resettlement, Division of Children’s Service whose work was focused on unaccompanied Central American minors in detention centers. C.C. welcomed this project extending help and assistance in any way needed.

The mural was painted on a vast stretched canvas. Traditionally, murals are painted directly on exterior or interior walls of buildings where they become signifiers of public spaces and urban landscapes. Given the fact that the participating artists could not leave the location where the mural was going to be painted, the mural became a flexible and transportable surface. After completion the mural could travel to disseminate the personal and communal histories narrated in vivid colors, lines and shades.

There were 57 participants in this mural project. Within a maximum-security facility the incarcerated youth are grouped in clusters of six to eight. For security reasons the participating artists could not congregate all at once in front of the mural. They would arrive to paint the mural one cluster at a time, understanding and agreeing to collaborate with the rest of artists whom they would never see. I was ready to face disagreements among the participating artists or controversy emerging from opposite ideas. This conflict never occurred.

SECOND CHANCES, mural, 2016. Photo: Claudia Bernardi.

SECOND CHANCES, mural, 2016. Photo: Claudia Bernardi.

A 15 years old Honduran boy, circumspect and rather shy, shared with me that he had been dreaming with the mural instead of having atrocious nightmares in which he relived killing people, or running away to avoid being killed himself. The minors are frequently unable to sleep for they arrive to this facility in fear and profoundly traumatized. A 16-year old Nicaraguan girl, with a strong personality and a notable beauty, a natural leader, a good collaborator, an interested listener, an astute thinker and an able diplomat, expressed her appreciation for the opportunity to be part of the mural project. ‘I want to thank you very much for this project of painting the mural because it makes me remember that I can still love. But I will return to my cell where I will have to forget about loving in order not to die.’

Second Chances transitions from left to right, from past to present to hopes for the future. Below a highway that is both distant and menacing, a man shoots another one in the chest. A red cloud disengages from the body. It is blood that evaporates from a life about to be extinguished.

The highway ends. A hole opens in the land. A man is about to execute an unarmed woman. Behind them a pile of body parts is guarded by vicious dogs. A blue truck brings more victims to the same unmarked location where everyone will be killed. These are men, women and even children who were unable to pay ransom to Narcotraffic cartels that control the Mexican side of the border. If they do not pay, they lose their lives. The young man who painted the execution scene and the pile of decomposing body parts had to add very little to his imagination to produce a painting devastatingly truthful. He had been there. He was forced to cut up the dead bodies to feed the dogs. Failing to do so would have cost him to be decapitated. Unimaginably, he escaped. He ran and walked, got lost and got disoriented. He knew that he had arrived at the United States when he was arrested by the US Border Patrol. The violence he escaped from his native Guatemala had brought him to El Norte. He had never imagined that he would end up in a prison. He was now trying to figure out what would happen to him next.

The highway turns into cross-roads, bringing questions, both geographical and existential. ‘What way should I go? What path should I take?’ Life was a puzzle, with some pieces that match perfectly one to the other and many more that would not fit. The young artists felt that they were offering themselves to the future with open hands, emptied of expectations, with the single hope that they could survive yet one more day. If they managed that, they were lucky. Although the participating artists were younger than 18 years old, several of them talked about their children. These young fathers feared that they would never become twenty years old. Whether in El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, Guatemala, or in the United States, the possibilities for them to be murdered before their twenty first birthday were higher than surviving. They wanted, desperately, to have children, to leave behind a memory of themselves, a trace of their DNA, a proof that they had existed.

SECOND CHANCES, mural, 2016. Photo: Claudia Bernardi.

SECOND CHANCES, mural, 2016. Photo: Claudia Bernardi.

The future which expands from the middle section towards the right of the mural shows small business such as a Chinese Restaurant run by a Guatemalan chef and a PupuserÃa that would bring delight to the Salvadoran community living in the United States. Singing professionally and building a career as a rock star seemed extremely improbable to the GarÃfona young artist from Honduras who painted that scene. However, he figured that the mural offered him a perfect opportunity to share his most beloved dream, whether probable or not. The last scene of the mural shows three mother hens crossing a road followed by three small chicks. There is no car to be seen but the highway is threatening, unpredictable. They may reach the other side of the road safely, or they may perish while trying. No one could really know. The incarcerated migrant minors agreed that they all deserved a second chance in life. A soft-spoken Guatemalan artist who painted a portrait of himself showing the traces of his attempt to commit suicide by cutting his wrists added: ‘I am only fourteen years old’.

When the mural was completed, the Deputy Director of Programs organized a small ceremony that included soft drinks and hot dogs. The artists were invited to talk about what they had painted. More importantly, perhaps, why had they painted it. The mural was an opportunity to share aspects of their lives, past, present and future that they had not disclosed before. One of the guards, whose task was to escort the participating artists from their cells to the improvised art studio, cautiously approached me. Noticeably moved, he said: ‘Art can save the life of one of these kids.’

SECOND CHANCES, mural, 2016. Photo: Claudia Bernardi.

SECOND CHANCES, mural, 2016. Photo: Claudia Bernardi.

I am unable to say that art could save anyone’s life but I am convinced that what art can do is to erase the distance between THEM and US; between people from one side of any border and people on the other. The creation of a community art project can expand the connections between people, isolated by prejudice, misassumptions, ignorance or indifference.

III. COMMUNITY AND COLLABORATIVE ART DURING COVID-19

AMONG THE COUNTLESS ADAPTATIONS that we have to face, accept and learn how to navigate during the COVID-19 pandemic, I include envisioning how to create a community-based art project without congregating. This sounds like an oxymoron.

I have worked with undocumented, unaccompanied Central American migrant minors incarcerated in maximum-security prisons for the past seven years. There have been obstacles to overcome, permits to get, confidentiality agreements to sign. But, eventually, the resulting murals have been welcome and celebrated. I was able to get authorization to remove a few of the murals for exhibition and these became the center piece of seminars and symposia that addressed immigrant rights, human rights and the United States criminal justice system. The selected murals were exhibited at the University of California, Berkeley; at the California College of the Arts and at the University of San Francisco. Currently, a mural painted in 2017, Déjame Florecer Una Vez Más/ Allow Me To Flower One More Time, is being exhibited at the Harvard Negotiation and Mediation Clinical Program at Harvard Law School.

This year, precisely in this month of May 2020, I was scheduled to facilitate a new collaborative and community-based project in a maximum-security prison where Central American migrant minors would collaborate with incarcerated local youth. This collaboration between migrant and local youth within the criminal justice system had not been explored. I had hoped that this new interaction would give the artists the opportunity to learn from one another while constructing the theme of the mural.

COVID-19 has not allowed that project to proceed.

Given the strict and necessary recommendations of social isolation and shelter in place, I cannot facilitate a mural project by being present among the incarcerated youth. Moreover, strict restrictions apply to the incarcerated minors. I spoke recently to the Deputy Director of Programs where the mural was to be painted. We shared our sadness for the obligatory changes that impede us to carry on the mural project as planned.

Being an artist is more than creating artworks. Artists are problem solvers who figure out how to challenge gravity, who learn how to work with materials that are vulnerable or dangerous. Artists figure out how to modify a space in such a way that one forgets that the space does not in fact exist. It is a visual illusion. With that in mind, I proposed the creation of a virtual mural that would collect drawings and paintings created as singular contributions with the understanding that those artworks would be part of a larger surface, an expandable mural. I would like to extend this new concept by inviting the participants to create a mural of voices, a landscape of their recorded opinions, declarations and ideas, describing their experiences while being incarcerated during this tragic time of the coronavirus pandemic. It will be a new version, with a different format, but with the same attempt to allow the participants to share their stories]

The imposed borders that rupture the social texture of communities all over the world demand urgent consideration. COVID-19 may provide an opportunity to create new bridges of understanding at a time in which solidarity and compassion may be the only and most powerful tools towards survival.

Note from the author: Due to the signing of confidentiality agreements, the name and location, city and state of the maximum-security prison where the mural Second Chances was painted as well as the names of the personal working within the criminal justice system cannot be revealed.