I. PREAMBLE: THREE WARNING SIGNS AND A TRASH WHIRLPOOL

II. OVERBURDENED WATERS

There’s hardly a river, stream, or brook that isn’t contaminated with the runoff from human misuse, whether industrial effluents, agricultural pesticides and herbicides, or worse. (The ‘worse’ could be bacterial contamination—the river as disease vector—or the dumping of radioactive wastes.)

—Marq de Villiers, Canadian author, Water

AN ONGOING LITANY OF TOXINS1. Our bodies’ health is inextricably linked to that of water, so why, oh why, are there are so many forms of polluted waters caused by hazardous spills; household waste; gasoline additive methyl tertiary butyl ether (MTBE); detergents; radioactive contaminants; volatile organic compounds; Atrazine (a weed-killer sprayed on corn and sorghum); antibiotic-resistant bacteria from large-scale meat farms? And the list goes on to include perchlorates (a chlorinated-hydrocarbon solvent best known as dry-cleaning fluid, but which also is a byproduct of rocket fuel that is sometimes dumped into rivers and streams near military bases and weapons manufacturing plants, contaminating drinking water in 35 states).

Another major problem today is household dumping. With more and more frequency, medications are turning up in rivers, lakes, and water supplies. Painkillers, hormones, antibiotics, tranquilizers, chemotherapy agents, and other drugs are excreted and/or flushed into municipal and domestic sewage systems. Most often, 50% to 90% of a drug is excreted unchanged, with the remainder excreted as metabolites, chemical byproducts of the body’s interaction with the drug. Cholesterol-lowering drugs have been found in the Danube River in Germany, in the Po River in Italy, and in the North Sea.

Besides pharmaceuticals, a recent analysis by the U.S. Geological survey listed personal care and ‘beauty’ products as among the contaminants found in water. Hair products such as mousses, volumizers, gels, hair sprays, thickening creams, and a variety of facial products including foundations, moisturizers, wrinkle creams, mascara, and concealers are washed off every day into water-treatment plants that cannot handle these products. Millions of pounds of these chemicals end up in our waterways.

Mining has long added nasty concoctions to our already-overburdened waters and produces more waste than most industries and cities. Even the products used to clean up chemicals after a road or rail accident can be dangerous. Studies have shown that chemical compounds used to treat a spill are as toxic as the spill itself. Aside from questions about whether or not radioactive materials should be used at all, waste products from their manufacture and disposal often leak into water, with the Fukushima plant in Japan being a major recent example.

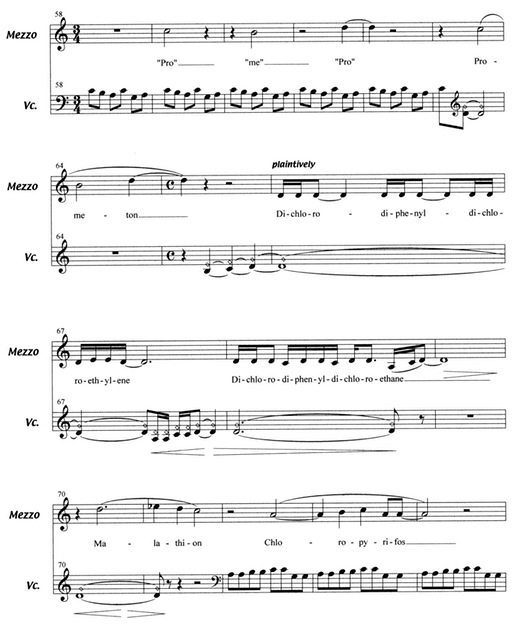

MUSIC. When I was invited to create a river project along the Calaveras River (which translates as ‘river of skulls’) in California, I accompanied a biologist each morning at dawn for several weeks as she performed water-sampling tests. Due to the region’s agricultural economy, high levels of pesticides were found in the river, including chlorpyrifos, dichlorodiphenyldichlorethlene (DDE), dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), diazinon, malathion, methyl parathion, pendimethalin, and prometon. This data lead to my creation of Clandestine Calaveras, a boxed set of nine postcard images of the Calaveras River overlaid with molecular structures and gas chromatography/mass spectrometer chromatograms of the chemical pesticides found there. A compact disk is also included in the boxed set, for which I commissioned a musical score by Andrew Ardizzoia, played by cellist Scott Halligan and sung by mezzosoprano Laurelle Mathison. The words featured on the CD are the names of chemical pesticides found in the Calaveras River.

I have also worked with musicians in communities in Ethiopia, Egypt, and Nepal. We write songs in their native language about ways to avoid contracting waterborne diseases.

Lake Tana, Source of the Blue Nile, Ethiopia, Muscians singing a song about how to avoid contracting schistosomiasis (aka bilharzia).

III. THE TERRIBLE BEAUTY OF WATERBORNE DISEASES

MICROPATHOGENS. In her prelude to my chapter in Water Library on polluted waters, Diane R. Karp, former Director, Santa Fe Art Institute, and former curator, Ars Medica collection, Philadelphia Museum of Art, writes:

One of the greatest global health issues revolves around the most basic human need—clean water. Focusing attention on the politics of water, and educating the public to the dangers inherent in not attending to its health and availability, has long been part of the mission of the international health organizations, but only recently has it become a topic for the arts. Basia’s concern for waterborne diseases contrasts the devastating force they have and the stunningly under-appreciated beauty of the appearance of the vectors. Contrasting the electron microscopic portraits of giardia or e. coli with their devastating power brings to our attention the dangerous and the beautiful aspects of these common organisms. The isolation and magnification of a single e.coli bacterium changes both the point of reference and our relationship to the organism. We experience it as a simple, beautiful, abstract form. Its ‘portrait’ is a thing of great beauty. As a co-habitating member of the intestinal retinue, it is an essential worker, helping to process fats and proteins while passing nutrients along to the bloodstream through the intestinal walls. As invading bacteria, it is potentially deadly.

Waterborne Disease Scrolls is an ongoing series of international projects investigating the pathogens in our water systems that cause such devastation. The dark, destructive side of water is as fascinating and rich in history as its more sanguine side. If we trained a microscope onto the same bucolic lakes and serene streams portrayed in historic paintings, we would discover a rich soup of living organisms, most of which are harmless to humans, but some of which kill. Usually, the organisms are ingested in drinking water, but sometimes a person might only wade into water and become infected.

The mortality rate data from water-related diseases is difficult to monitor and inadequately recorded, but staggering estimates have been derived in a number of ways. Natural Resources Defense Council scientists estimate that every year approximately seven million Americans become sick from contaminated tap water, which sometimes proves lethal. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), lack of clean water accounts for 80% of all diseases in poor nations. Two-thirds of the world’s householders must carry their water into the home from outside sources. This burdensome task usually falls to the women and girls, some of whom trudge 6 hours each day, hauling water. One in five people in the world do not have clean water. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) ‘Fact Sheet 112’ notes: ‘Every eight seconds a child dies from a water-related disease,’ and, ‘Each year, over 5.2 million people in developing countries die from water-related diseases.’ A BBC reporter phrased it this way: ‘The number of deaths due to water-related disease is the same as twenty jumbo jets crashing each day.’

WATERBORNE DISEASE SCROLLS. I photographically enlarge images of microscopic waterborne pathogens and then heat-transfer them onto scrolls. The scrolls I completed while in India were made of sari silk, partially because water can be strained through this fabric to reduce the number of organisms that cause infections. Sometimes I have transferred images of Escherichia coli and Campylobacter jejeuni onto local hospital bed sheets. In Ethiopia, at the source of the Blue Nile, I used hand-woven cotton fabric purchased from a local woman at a market. The scrolls roll up to fit into their own carrying cases complete with shoulder straps. All of this work functions within the traditional museum or gallery setting, yet their transportability eludes to the human body as a carrier whose role in spreading disease is magnified by globalization.

My work explores numerous waterborne diseases whose transmission occurs when people drink contaminated water or submerge themselves in water for bathing or swimming or for ceremonial or religious purposes. A few examples include:

1. Giardia (lamblia) duodenalis. My investigation into waterborne diseases began when I was diagnosed with Giardia. During my stay in Indonesia on a Fullbright Scholoarship, I swam in Javanese and Balinese rivers that definitely were not clean. I went swimming in questionable streams for the pure love of immersion, but when I returned from Indonesia I spent hours in another type of immersion, this time at the medical library, studying books on parasitology. When I first saw an enlarged image of Giardia, I laughed out loud. It looks like a fat sperm with two large eyes (the nuclei) and a smile (the median bodies). A cross-section of intestinal tissue infected with G. duodenalis lamblia looks similar to an aerial view of a fertile green field.

One does not have to go to an exotic locale to contract Giardia. It is endemic in the western United States due to cows’ fecal matter entering streams. It is often referred to as ‘beaver fever,’ because beavers can be carriers of the cysts that discharge to infect people. I grew up camping in the mountains of Colorado, where we sometimes drank directly from mountain streams. We would no longer consider doing this, even though the cold, clear streams still look just as ‘clean.’

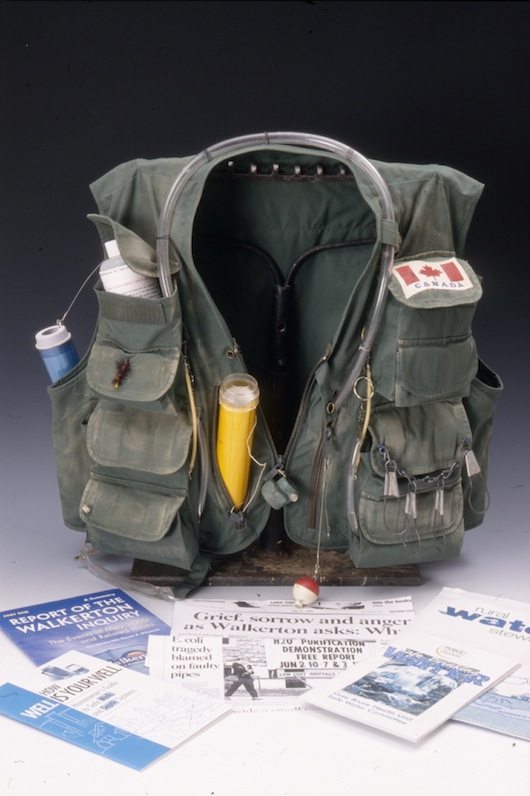

2. Escherichia coli O157:H7. Many E. coli bacteria are harmless and live in the intestines of healthy humans and animals, but the O157:H7 strain can be deadly. E. coli O157 is the bacterium that appeared in 2000 in the drinking water of Walkerton, Ontario, Canada, where half of a small rural town of 4,000 became sick and seven people died from ingesting the infected water. Heavy precipitation had pushed the Saugeen River over its banks, through a cow pasture and into an unmonitored well, which then entered the municipal water system. On the first anniversary of this event I was invited to Walkerton to create work around the stories told to me by the community members who had survived.

3. Dracunculus medinensis. This roundworm is better known by the English name of ‘guinea worm’ because of its assumed home in Africa. Ancient Egyptian medical references from as early as the 15th century B.C. document this parasite, and calcified guinea worms have even been found in 3000-year-old Egyptian mummies. Copepods (tiny aquatic crustaceans) ingest their favorite food, guinea worm larvae, which enter humans through drinking water drawn from shallow pools or ancient wells. In the stomach the larvae leave the copepods and find their way to deep body tissues, where they develop into the adult stage in about one year. A 2002 New York Times article aptly described the process: ‘It slithers around their innards, sometimes for as long as a year, until it opts for an escape.’

The 3-foot-long female worm lives in subcutaneous connective tissue just below the skin where its secretions eventually cause a blister to erupt, usually at the extremities of an arm or leg. An infected person will often seek relief from the burning sensation by soaking in water as the worm emerges. Upon contact with water, the blister breaks open and the anterior end of the worm emerges to spew thousands of larvae into the water where they are eaten by copepods, and the cycle begins anew. The worm can now be removed from the body and is often wound around a small stick. This slow, painful process can take up to two months.

The Carter Center in Atlanta, Georgia, has attempted to eradicate guinea worm disease worldwide through filter systems, educational awareness programs, and low-technology methods to encourage behavioral change. Since there is no cure or vaccine, this disease can only be prevented, and it has now been reduced by 98%.

During a trip to India, I visited many of the architecturally beautiful stepwells in Gujarat and Rajasthan, where I suspended and documented sari-silk scrolls with enlarged images of the guinea worm. These ancient water structures used to be one of India’s major sources of water, but now, partially due to this worm, the stepwells play only a minor role. Because the process of infection cannot be seen, it is sometimes difficult for people to associate the disease with their water source.

4. Schistosoma. The intermediate hosts for schistosome flukes are snails. Eggs hatch in fresh water, develop further inside the snails, and are then released back into the water where they invade humans through the skin. Inside the human host, the larvae travel via the bloodstream to the bladder, lungs, or liver, where the worms mature and begin the cycle again by laying eggs. Infection of the liver is the most common cause of death. A collaborative grant with the biology department of the University of New Mexico took me to Egypt, Ethiopia, and Nepal to research and record Schistosomiasis in a documentary film.

A brief excerpt. Running time 19:34 minutes.

5. Vibrio cholerae. Fecally contaminated water is responsible for most outbreaks of cholera. The diseased patient often has severe vomiting and the white diarrhea that is referred to as a ‘rice water stool,’ causing severe dehydration. Aid can come in the form of rehydration therapy, the administering of small packets of glucose and salts that restore water and essential electrolytes to the body. Cholera outbreaks sometimes occur after major disasters, due to lack of sanitation and clean drinking water. Surviving victims of an initial disaster thus can be hit with a second wave of destruction, such as happened in Haiti in 2010.

CONTROL EFFORTS. Great strides have been made in the control of all of these infectious waterborne diseases. However, in some countries and with some of the parasites listed above, there is still a long way to go. A few of the multifold control efforts include education, medications, vector control, and vaccination. Drugs can, of course, work wonders for many of these pathogens. Controlling vectors such as hosts that spread parasites can also help alleviate problems, although this requires follow-through and determination. Instead of using harsh chemicals, more natural control methods include removal of vegetation from infected canals and introducing biological predators. For example, fish, competitive snail species, and crayfish that eat snail hosts have been proven effective in fighting schistosome worms in some regions. Research is under way to discover and produce vaccines that can assist in preventing infection and lowering the cases of reinfection for some of these diseases.

III. SACRED WATER

Rather than impose our human-centered perspectives on other forms of life, we should humbly seek to learn the ways of the natural world and appreciate its inherent sacredness.

—Nathaniel Altman, medical writer and researcher

Everything in the water cycle is interconnected. If each of us thought of water as sacred, perhaps—just perhaps—a shift of attitudes and values might occur and manifest through small and large actions of protection and preservation. It is difficult to desecrate that which we revere.

My life has been blessed with visits to sacred water sites. I have had the privilege of hiking up the mountain to Pura Besakih on the island of Bali with Hindu priests carrying holy water; attending a ceremony for Yemanjá in Brazil; visiting Holy Wells in Ireland; seeing the Chalice Well at Glastonbury, Somerset, England; wading in sacred rivers in India; and sipping holy water in Thailand. Each year, on December 16, Our Lady of Guadalupe Feast Day, in the South Valley of Albuquerque, a priest consecrates the colorfully decorated statues of Guadalupe with sanctified water. These were special occasions, but in its essence, all water is holy, whether in a humble ephemeral puddle, a raging river, an enormous lake, or our drinking glasses. The words ‘whole,’ ‘health,’ and ‘holy’ are related etymologically.

IV. A CAUTIONARY TALE: POEM FOR YEMANJÃ

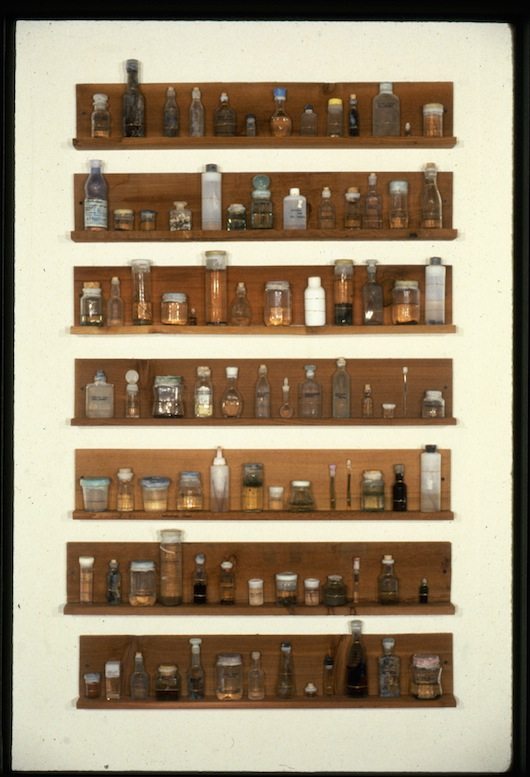

PHASE ONE: COLLECTING. The title of the work, Poem for Yemanjá, refers to the Afro-Brazilian orixa of the ocean and Mother of the Fishes2. Over several years, my collaborators and I fill receptacles with global waters from oceans, seas, holy and healing wells, lakes, bays, melted snow, glacial water, and rivers. Receptacles include a film canister labeled ‘RÃo Solimoes, Amazonas’; a vitamin bottle with water from Hjalmaren Lake, Sweden; and a small, green glass receptacle bearing an inch of Lake Debo from Mali, Africa.

Each container has a story to tell about how it is obtained—a hike up a mountain in Peru for melted glacier water or a trek along the Tulangbawang River in Sumatra. A physics professor brings water from the Sacred Well at Delphi, Greece. A former student mails a few drops from the Pacific Ocean at Dunedin, New Zealand. My son, Derek, brings water from Scapa Flow, in Scotland’s Orkney Islands. A friend in Manhattan delivers a tiny, blue, fish-shaped bottle containing water from an eventful and dangerous trip to the source of the Niger River. On the shelves of Poem for Yemanjá a new geography is created: the Hudson River is found between the African Niger River and the Peruvian Urubamba River.

PHASE TWO: DECONSTRUCTION. Poem for Yemanjá was included in ‘Imaging the River,’ an exhibition at the Hudson River Museum in Yonkers, New York, in 2004. After the show ended, the curatorial staff wanted to keep the sculpture for the museum’s permanent collection and it remained there for a year. But an idea began to gnaw at me. With so many bottles, jars, and vials of water, I grew concerned about the physicality of containment. Penned-up water is no longer alive. Each bottle had been sealed, denying its ability to breathe. The liquid could no longer flow freely and was therefore essentially dead.

I asked that the sculpture be returned to me, so that the containers of water on the seven shelves would not languish in a storage vault or on a museum wall. A month later an enormous wooden crate arrived at my studio. It was time for deconstruction, and a new phase of the work, which I had not initially foreseen, evolved.

Slowly, I realized that, at some point, all of these waters will have to be released. I, of course, did not have the funding to travel all around the world returning drops of water to the exact locations where they had originally been scooped up, therefore I decided the contents of each container could at least be added to a flowing river, lake, or sea. This would allow each H2O molecule to rejoin the vast hydrologic cycle. I advised participants to boil the water, thereby removing any possible pollutants and also releasing some of the moisture into the atmosphere as steam.

Some friends tried to dissuade me from altering the original work. ‘Maybe you could think of it as a water bank, and it will be the only water left after we have destroyed the waters of the world,’ one friend suggested. But this part of the work became inevitable, based on my continuing water research. Since change and ephemerality are constant companions in our lives, I did not mind altering this sculpture and taking it into another phase.

Numerous times, I have witnessed Tibetan refugee monks in the United States creating slowly, grain upon grain, holy sand mandalas. In this ancient Buddhist tradition, the image of flowing water signifies the Dharma teachings that flow to all areas of the planet and are accessible to everyone. A painting of a water pitcher is an offering water symbolizes a substance to be given away. Water has no value and all value, and has the same merit as gold. It is the purest offering that one can give. Peaceful deities symbolizing the washing away of disease, and the ability to transmute the ordinary into the enlightened, often hold bowls of water. After weeks of work on Tibetan mandalas, monks perform an elaborate ceremony in which they use a small whiskbroom to remove the design and sweep the sand into a pot. If viewers are not expecting this, there is often a gasp from the audience. Why destroy an intricate pattern that took so long to create? But, of course, that is the whole idea. It is about ephemerality. Nothing in life lasts forever. The container of sand is carried to the river, where the monks pour the sand into the flowing water.

FINAL PHASE: DISPERSAL AND RESTORATION. The returning process began. Friends around the world have been dispersing the waters from this Poem. After being boiled, a container from Greece is poured into a river in Mexico City. One bottle of water from Wisconsin is decanted into the Arctic Ocean, and another from the Hudson River enters the Seine in Paris. Of the original 91 receptacles of liquid, there are still many yet to reenter the water cycle, and just as each ‘gathering’ had a story to tell, so does each dispersal.

Patrick Nagatani dispersing water from Saudi Arabia into meltwater, Mendenhall Glacier near Juneau, Alaska.

When Kirsten Buick, an art historian friend, was trying to dissuade me from changing the piece, she argued, ‘It is a reliquary for stories, tales about water that need to be remembered.’ It is this comment, which helped spark another component of the final phase of the Poem. The empty receptacles that had once held water now hold stories about the return of the water, written on pieces of paper and put in the bottles. The sculpture will be reassembled with the bottles of words, and returned to the museum. Stories cannot be contained. The tales will hover in fog, mist, and clouds; rain down during thunderstorms; condense in the morning dew and evaporate again to rejoin the cycle. Listen closely.

END NOTES

1. Some of the thoughts in this essay are based on excerpts from my book Water Library (2007).