Location: Iran and the San Francisco Bay Area, CA.

A decade of Iranian environmental art was showcased in Transylvania, Romania, in July 2015. Called The Living Spaces, the exhibition curator Mahmoud Maktabi1, selected 30+ artists: Nooshin Naficy, Ahmad Nadalian, Tara Goodarzy, Shahrnaz Zarkesh, Atefeh Khas, Minoosh Zomorodinia, Farzaneh Najafi, Fereshteh Alamshah, Asiye Mohamadian, Hamid Nourabadi, Mahtab Ghaemi Manesh, Mahmoud Maktabi, Koroush Golnari, Mojtaba Ramzi, Karim Alahkhani, Mahdiye Dehghani, Hamed Mashmoli, Parisa Rajabian, Anne Tatari, Atefeh Arani, Siyavash Amiri Rad, Shirin Mohseni Nasab, Fereshteh Zamani, Hamid Khandan, Earth Art Group, Low Art Group, and Open 5 Group.

AS ONE OF THE FIRST ARTISTS and photographers interested in environmental art in Iran, and as one who has observed and collaborated with many of the artists in this movement, I thought it would be valuable to survey a selection of the exhibition’s artists and compare various aspects of the works with art of the same genre from the United States. I was most interested in writing about women artists in Iran because I believe that many women, despite the challenges they have experienced living in Iranian society, find nature to be a peaceful place for creating artworks and for revealing their inner struggles. Some of these artists have been creating art in nature continuously, while others have changed their practices through the years and do not consider themselves ‘environmental artists’ per se. Some of them have worked for a short time in nature, although all of these artists have pointed to nature in their work. Nature offers a safe platform to engage and express their intuitions. It is a meditative practice that allows an intimacy with nature for Iranian women artists. As Nooshin Naficy2 says, ‘Working in nature requires some isolation, immersion, deep listening, observing, and finally something of a meditation.’

Looking back at a decade of efforts by Iranian environmental artists in the recent Living Spaces exhibition one may not see great progress. The works are repetitive and meditative, with many appearing to be influenced by Christo and Jeanne Claude, Andy Goldsworthy, Nils-Udo, David Nash and Iranian artist Ahmad Nadalian3, a pioneer of this movement in Iran. However, knowledge of the rich Iranian history of mythology and literature provides a number of different interpretations. From this survey, artists point to their desire to be part of nature, to protect the environment as important subject matter globally and locally, and to sustain the roots of poetry in their works.

From my point of view the environmental art movement today resembles the feminist movement of the early 1970s. In that decade many women artists utilized their bodies in their artworks to communicate their opposition of society. Iranian environmental women artists today also express themselves through their bodies, although hidden behind the maternal layers of nature. They address the ‘feminine,’ a term that Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee uses to convey the mystery of creation.4

Some exhibition artists utilize ritual to address the spiritual and the divine. Consciousness of ‘being’ connects inner and outer life and is indicated in the women artists’ works through meditations in nature. On one hand, artist Tara Goodarzy,5 claims that she searches for answers to the questions, ‘Who am I? Where do I belong?,’ a quote from the well-known poet and Sufi mystic Rumi. Goodarzy states, ‘My religion, Islam, adores nature and its beauty, and all Muslims are strictly invited to preserve the earth and the environment.’ Another artist, Mahdiye Dehghan, emphasizes perception of the self and its environment as encouraged in the Quran.

On the other hand, Atefeh Khas6 says, ‘When you are living in a religious country, with a lot of advertisements about that religion, it’s impossible not to be affected by it.’ She describes her work as a reflection of her identity: ‘My identity is not separate from my gender, and being a woman and the experience of being a woman completely affects my works.’

The root of spirituality is presented in other works: ‘I am interested in the connection between primitive man, nature and ancient rituals,’ explains Nooshin Naficy.

Women artists describe their desire with nature as a feminine sensibility. They insist that their relationship with nature is a relationship with a force that is of the same gender. ‘I believe that there is a relationship between my soul as a woman artist and my works, because what I do is a reflection of my characteristics,’ says Mahtab Ghaemi Manesh. Fereshteh Zamani points to the power of giving birth and its similarity with the power of Mother Nature. She describes her feelings about the connection of humans and nature as family, and believes in protecting the family by saving nature.

Because manipulating the natural environment can cause problems for wildlife, some artists avoid these actions and are hopeful that by creating art in nature, they can bring awareness to the public to save the environment globally. Fereshteh Alamshah in her works uses the remains and bones of dead animals in her investigations of the river not only to create meditative works, but also to reference the power of divine. She illustrates her opposition to drought by using natural elements from the site and insists on protecting the environment.

Creating organic patterns with natural materials is another technique that artists use to manipulate nature. Farzaneh Najafi borrows Iranian patterns and intuitively manipulates the natural materials at the sites in her works. She creates mostly small gardens. Her ritualistic action reminds us of indigenous traditions and the sacred ecology of connecting with nature. Asiyeh Mohamadian not only looks for the beauty in her works but also for a delicate connection between humans and nature, while utilizing natural materials.

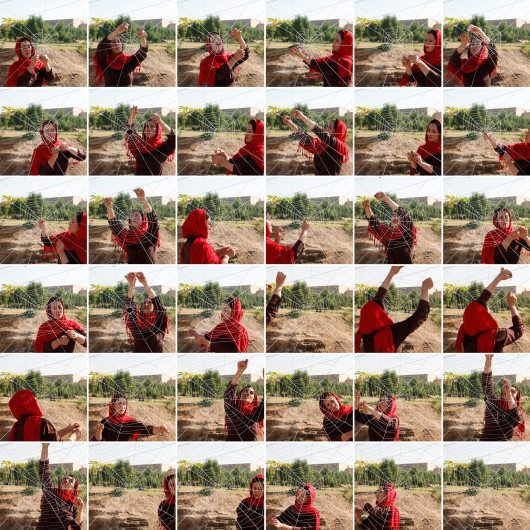

Perhaps one interpretation of the power of this kind of work is that artists working with natural materials can positively heal the self by exhibiting their struggles. Shahrnaz Zarkesh unconsciously references the capturing of the self, despite the feminist reading of her piece. In I am caught in the web made by myself, she insists on expression of the self. She spins webs in different locations and performs in front of the webs. Parisa Rajabian describes it, ‘Through my artworks, I share my struggles for existence with my audience.’ She points to her immigration to a new country in the Songs of the Wind.

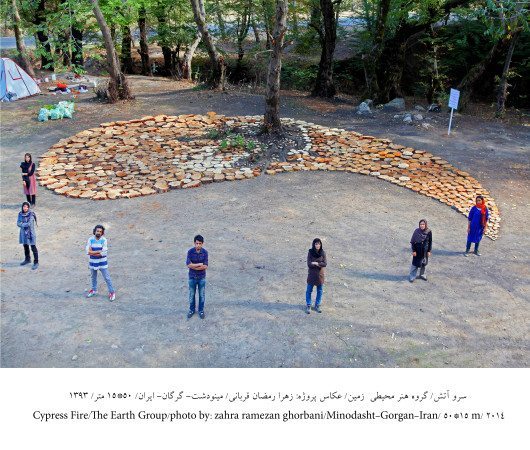

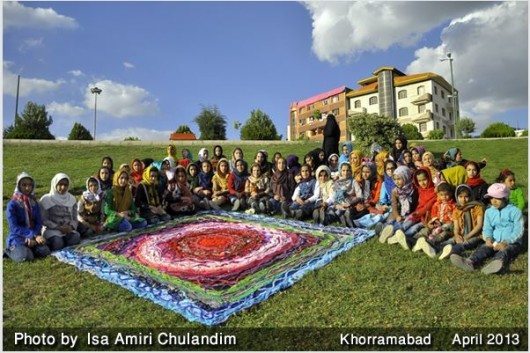

Nurturing is another aspect of these works that shifts to collaboration for a number of the women artists. Open 5 Group7, Low Art Group, Gudar and Earth Group include mostly women. The desire to care for and encourage close relationships among women artists is created collectively through working on large-scale art pieces in nature. Each artist develops her own practice, influenced by the collective. Tara Goudarzi has created many artworks collaboratively with her students over several years. She guides them to use recycled materials so that they protect the environment while creating large installations in different environments. The Earth Group has focused on the care of and respect for nature, and they hope to create positive effects on the Earth’s natural cycles. Although not all of these groups rely on the collaborations, group members learn from the collaborative experience then continue their work in their own ways.

All of the artists discussed here respect nature and hope to continue their practice despite a lack of major support from outside organizations or the government. They all hope that one day an Iranian organization will step in and provide a funding to support the artists in the field by publishing their ephemeral works, such as the Yatoo-i International Project in South Korea does, to bring awareness to the public through their visions.

Finally, I would like to emphasize that the feminine and ritual is represented in most of artworks discussed here by pointing to a quote from Vaughan-Lee ‘s book The Return of the Feminine and the World Soul9:

‘Without the feminine nothing new can be born, nothing new can come into existence—we will remain caught in the materialistic images of life that are polluting our planet and desecrating our souls.’

WOVEN IMAGINATION, Tara Goodarzy in collaboration with her students. Photo by Amiri Chulandim, Khorramabad, Iran, 2013.

END NOTES

1 See www.mahmoudmaktabi.com

2 See www.nooshinnaficy.com

3 See www.riverart.net

4 Llewellyn Vaughan-Lee, The Return of the Feminine and the World Soul (The Golden Sufi Center, 2009).

5 See www.arttara.com

6 See www.atefehkhas.com

7 See www.5baz.com

8 See www.yatooi.com

9 Ibid.