Open only to WEAD listing artists and members, each Portfolio is curated by the Editorial Committee to showcase artists whose work reflects diverse approaches to environmental and social justice art.

ARTISTS

HEIDI BRUECKNER

KITE (Aka Suzanne Kite)

PETRA KUPPERS

ELIZABETH LEADER

CHARMAINE LURCH

BARBARA ROUX

CHRISTY RUPP

FERN SHAFFER

JAMILA RUFARO

KANYON SAYERS-ROODS

TARA JOVANCEVIC

WATER KERNER

CLAUDIA FUENTES DE LACAYO

HEIDI BRUECKNER

My work focuses mostly on cultural allegories and norms conveyed through a collage-like juxtaposition of figurative imagery, symbolism, and elaborate patterning. Often the figures personify the precarious, dark, grotesque, and sleazy side of human nature, subjects by which I am continually fascinated.

These topics seem to require, and in fact dictate, frontal, discomforting, and intrusive compositions. I revel in playing with bright color and pattern, tilted and flattened space, and distorted form in order to achieve this needed psychological expression and visual activity, but also to create an element of humor and fun.

In my portraits, similar formal characteristics are used to evoke more intimate narratives, often with a layer of social commentary. ‘Domestic Violence (Self-Portrait)’ is part of a series of self-portraits posing with kitchen tools held in a threatening manner. It references ‘being stuck in the kitchen’ but humorously suggests a solution on how to get out. The figure is semi-transparent, as referenced by the background pattern showing through the form. This symbolizes the fact that in so many ways women are still not treated as “whole” people.

KITE (Aka Suzanne Kite)

Everything I Say Is True is a multi-media performance work by Southern California-based, Oglala Lakota artist Kite, aka Suzanne Kite.

Kite aka Suzanne Kite is an Oglala Lakota performance artist, visual artist, and composer raised in Southern California, with a BFA from CalArts in music composition, an MFA from Bard College’s Milton Avery Graduate School, and is a PhD student at Concordia University. Her research is concerned with contemporary Lakota mythologies and epistemologies and investigates the multiplicity of mythologies existing constantly in the contemporary storytelling of the Lakota through research-creation, computational media, and performance practice. Recently, Kite has been developing a body interface for movement performances, carbon fiber sculptures, immersive video & sound installations, as well as co-running the experimental electronic imprint, Unheard Records.

PETRA KUPPERS

Salamander Project: Josie Noble, Aotearoa/New Zealand

Petra Kuppers is the Artistic Director of The Olimpias (www.olimpias.org), an artists’ collective that creates collaborative, research-focused environments open to people with physical, emotional, sensory and cognitive differences and their allies. We usually meet in public parks and other open outdoor places, and make disability visibility part of our creative engagement with each other and our world, focusing on biodiversity and respectful engagement with the land. We use presence, slowness, pedestrian movements, a poetics of words and bodies, and the deep affective register of touch to share our beauty and our critique. Resulting videos, photographs, community writing and installations have travelled around the world.

Fuller Statement: http://www.goddard.edu/people/petra-kuppers

ELIZABETH LEADER

‘Tires Underwater’ 40″h x 58″w Mixed media

Buffalo NY artist Elizabeth Leader received her MFA from Rochester Institute of Technology, and went on to work as a teacher, graphic designer and painter.

All that I experience inspires me to use a wide range of materials and techniques to communicate my ideas about people, the environment, and the stuff we throw away.

TROUBLED WATERS

The issue of our consumption and thoughtless disposal of products is now rising in human consciousness. We are beginning to understand that, in overwhelming nature we are overwhelming ourselves. Calls to make better choices are being heard from many directions. My work is one of those calls.

Three of my water pieces have been part of the ‘GYRE, the Plastic Ocean’ exhibit now traveling around the United States under the auspices of the Smithsonian. To contact me, visit my website at www.elizabethleader.com.

CHARMAINE LURCH

Re-reading, 2017 charcoal on paper, 36×36″ “we share our lessons of unknowing ourselves and in this refuse what they want us to be” K. McKittrick

Charmaine Lurch is an interdisciplinary visual artist whose work draws attention to human-environmental relationalities. Lurch’s paintings and sculptures are conversations on infrastructures and the spaces and places we inhabit. Working with a range of materials and reimagining our surroundings—from bees and taxi cabs to The Tempest and quiet moments of joy, Lurch subtly connects Black life and movement globally.

Lurch offers us materials that are seemingly simple and familiar. Figures marked in charcoal, perform dynamic movements, allowing us to visualize active presence. Paint both pleases and jars vision to create new ways of seeing and knowing. Wire takes up space, is a drawing in space, wire moves through space. Removed from tooling & machining, the formations casts shadows, trace landscapes, and is a means to mark the inside/outside of things. These elements are her expressive and textural messengers. Bound together with research, they create signifying forms, that seek to re-configure and rewire perception and ideas.

Lurch holds a Master’s in Environmental Studies from York University, is a graduate of Sheridan College – Faculty of Visual and Creative Arts, studied at Ontario College of Art and Design University, and The School of Visual Arts in New York City.

BARBARA ROUX

Channeling a Blackbird, digital print 2019.

My recent work continues to address my engagement with local native habitats in New York State. I am both an environmental artist and a conservation activist. One grows out of the other. Through my use of symbols like the house, birds, trees and moons I connect with the rituals of the earth’s cycles. By connecting these symbols with a fragile site I magnify the importance of these places to the survival of our planet. ‘Channeling a Blackbird’ relates to my awareness and concern over the threats to tidal marshes from habitat destruction. Animals that breed in and are nurtured by these places are disappearing, among them the red winged blackbird.

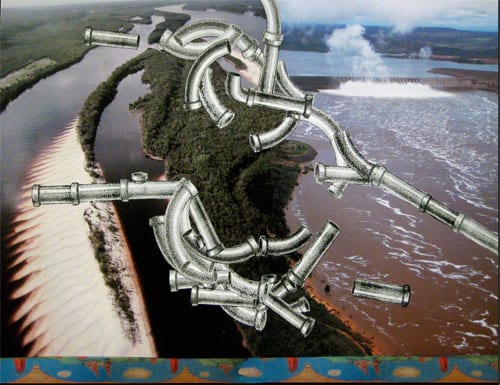

CHRISTY RUPP

The earth is under assault by new high tech ways of extracting minerals. Natural substances like salts, ores, fossil fuel, and uranium are harmless if left below the surface. But when they are in the way of greedy fingers they get carelessly abandoned, combined with toxic chemicals dumped on the earths skin to ruin forever the balance of living things. Hydro fracturing and Mountaintop removal are two in a long list of weapons of mass destruction designed to vacuum up energy producing minerals as fast as possible, generating maximum profits for investors, requiring less personel and more heavy equipment. High tech Rambo style mining leaves the landscape a blenderized corpse, fragments of life which are polluted beyond reclamation.

Source: www.christyrupp.com

FERN SHAFFER

Photograph Ritual #2 on the edge of the pacific Ocean. The concern was for the water.

My interest in science has always directed me to information about the environment. By recognizing how everything is interconnected, our society can avoid mistakes that will only come back to haunt us. It makes no sense to poison the water when we will ultimately be the ones to consume it. The pattern is repeated over and over again revealing the crisis potential of our culture’s desire for immediate gratification. Living in an increasingly dangerous, toxic, and stagnant environment, for both animal and plant life, led me to investigate the dilemma through my art.

-Fern Shaffer

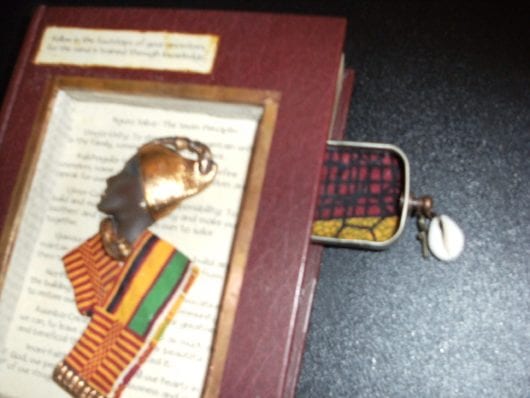

JAMILA RUFARO

Jamila Rufaro is a native New Yorker with roots in Jamaica. She creates mixed media assemblage, altered books and artists’ books. Her artwork is often about reuse of basic living elements sometimes in absurd ways. The results are deconstructed to the extent that meaning is shifted and interpretation becomes multifaceted. Juxtaposition that provokes a smile, or even better a laugh, is her favorite. She now lives in Palo Alto, CA, teaches book art classes and is a member of Bay Area Book Artists. You can see more of her work on her website: www.jamilarufaro.com.

Jamila Rufaro is a native New Yorker with roots in Jamaica. She creates mixed media assemblage, altered books and artists’ books. Her artwork is often about reuse of basic living elements sometimes in absurd ways. The results are deconstructed to the extent that meaning is shifted and interpretation becomes multifaceted. Juxtaposition that provokes a smile, or even better a laugh, is her favorite. She now lives in Palo Alto, CA, teaches book art classes and is a member of Bay Area Book Artists. You can see more of her work on her website: www.jamilarufaro.com.

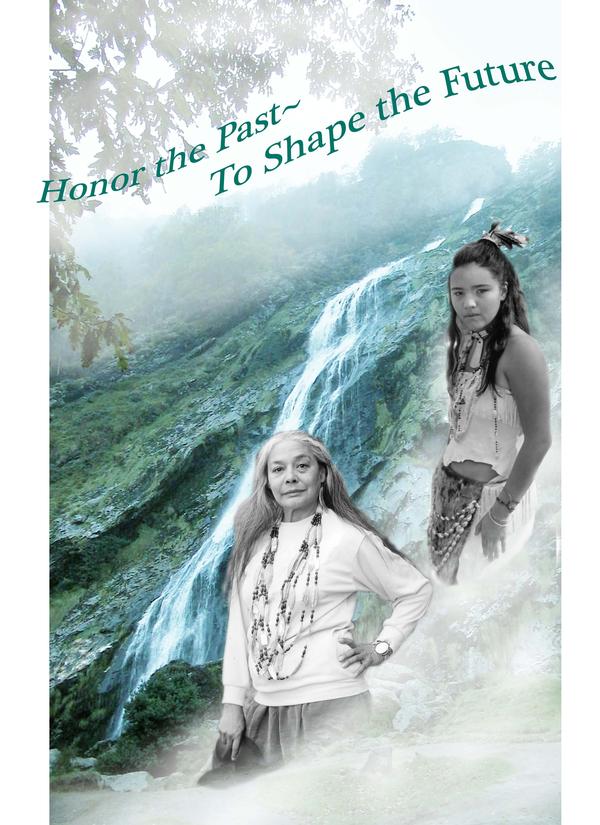

KANYON SAYERS-ROODS

Honor the Past to Shape the Future – Graphic Art

A Costanoan Ohlone and Chumach, Kanyon Sayers-Roods also goes by her given Native name, Hahashkani, which in Chumash means “Coyote Woman.” She is proud of her heritage and is very active in the Native Community. She is an artist, poet, author, activist, student and teacher. I am a creative artist ever inspired by nature and the natural world. I make a difference in the lives of others by sharing my life experiences and knowledge about California Native Americans. I have the gift of communication, and challenge myself to utilize this gift to deliver powerfully effective messages for others. My personal mission, which I intend to carry out in my career, is to contribute toward the goal of global education with emphasis on promoting understanding of the relationship between humanity and the natural world.

TARA JOVANCEVIC

False Starts

Multidisciplinary artist practicing in site-specific installation and works on paper, Jovancevic was born in Bosnia and Herzegovinia, and came to the U.S. in 1991 as a student. She now lives in Chicago. My art speaks of things I have a hard time talking about. As an individual from a war-torn country I create art about detachment from physical and true home, sense of identity, pursuit of belonging and reconciliation. These themes are intertwined with a sense of fragility and destruction of nature and of life itself. The materials I use amplify the ideas that I’m working out in my art. I’m always on the lookout for leaves, wood, old metal scraps, books and random things that I can incorporate into my pieces. There is a sense of redemption at the end of the process. A discarded material is given a new, repurposed life—so is the artist.

WATER KERNER

STRENGTH IN DIVERSITY

WATER KERNER began creating art at the age of 5 in New York. She received her BFA from MICA and was awarded the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture Scholarship. Upon completion, Water was honored with the ‘Skowhegan Sculptor Merit Award’. In 1992 Water moved to Los Angeles to open the pioneering studio L@it2’d (‘Latitude’), known as the first Hollywood animation boutique to create digital art for TV & Film studios utilizing cutting edge hardware and software on Apple computers. Lati2d garnered a myriad of creative awards and recognition over the 17 years Water acted as President, Director & Chief Artist/Designer. Kerner decided in 2009 to focus on her fine art inspired by the magic of light, motion and/or sound. Her installations, sculptures and paintings have been shown in cities across the United States and abroad. For more information: www.waterkerner.com

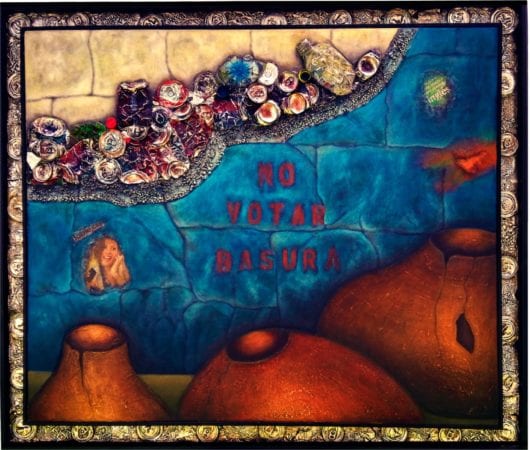

CLAUDIA FUENTES DE LACAYO

My Neighborhood 1, mixed media, 135×115 cm. 2016. The three cultures cohabiting Latin America.

I search inside myself the vestiges of ancient cultures that have inhabited our continent, and specifically my country, Nicaragua. The pre-Hispanic pottery was a product of the earth and every vessel was not only an object of daily use, but a sacred object, the container of life. I add to the buried memories of our pre-Hispanic cultures and the colonial walls raised over them, the new walls of popular culture, symbols of the ephemeral and the disposable. There are intentional references to numerous stylistic features and ideas about pre-Columbian and Colonial Art. Currently, I started using topics from popular culture, like graffiti and printmaking techniques. Working in tune with tradition and the expressive opportunities in painting, I dig the unknown dimension that lives within me and all of us.