Location: The Polar Regions--The Arctic, Antarctica, Greenland, Alaska, et al

INTRODUCTION

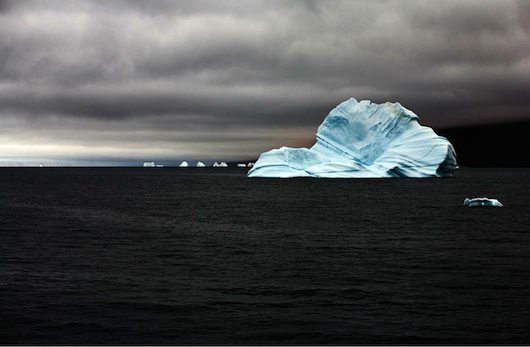

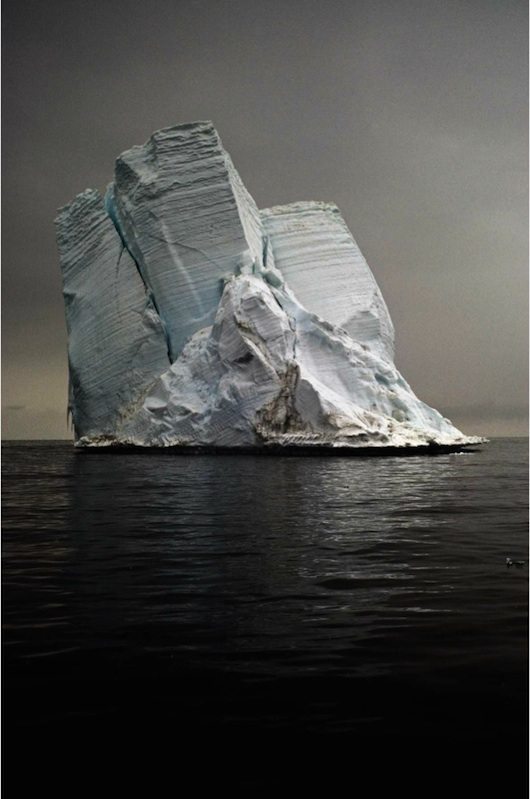

Camille Seaman is a TED (1) Fellow, award winning photographer who travels to the ends of the earth–the most frozen polar regions, to photograph the lives of icebergs as they calf, float, change shape and appear to vanish. Far from seeing them as “lost” she approaches icebergs as ancient ancestors, and that she is shooting (digital and film photos) individual portraits of their life cycle, saying that as icebergs melt, they add nutrients to enrich ocean life and replenish the oxygen we breathe. Her work is published internationally in magazines and books.

WEAD Website Producer and Editorial Assistant Krystle Ahmadyar (KA) interviewed this itinerant artist in her SF Bay Area studio, on a rare opportunity when Seaman (CS) was home working. They talked about Seaman’s ancestry and artworks, and her deep philosophy on the web of interconnected life on earth.

I. TRIBAL FAMILY INFLUENCES

KA: Your father was from the Long Island, NY, Shinnecock tribe. How did Shinnecock culture shape your perspective?

CS: The Shinnecock tribe influenced me on many levels, especially in how I see the world. My grandparents, father, aunts and uncles all lived on an island near South Hampton, (Long Island, NY). I was raised communally. There were always a lot of children and family around for me to play with.

Its not well known but there are 24 active tribes on Long Island right now. The Shinnecock recently achieved federal recognition. No tribe has done this in a long time. We are quite lucky. Shinnecock is such an old tribe that we had a treaty with the Providence of New York but not with the United States because it didn’t exist yet.

KA: What sort of relationship did you have with your elders?

CS: Each adult was in charge of an aspect of our education. For example, one aunt would walk us through the woods teaching us about plants and their healing properties. Another aunt taught me how to make moccasins and tan hydes.

It was my grandfather who was key in helping me shape my world understanding- that I am not separate from this thing that I live in. We are all apart of this world. It is all interconnected and interrelated.

Because of being raised communally, it wasn’t until my mid-20’s, I realized the pervasive isolation in western society. It’s one of society’s great illusions. We aren’t alone; we even share each other’s molecules.

II. CAMERA

KA: Did you start playing with the camera at an early age? And how did photography become your medium?

CS: I didn’t have a formal art education. I started using the camera to capture my experiences at 15. I was having a hard time with my mom and left home. My school recognized that I was at risk so they gave me a Nicromat camera to photograph my experiences. There was no formal teaching on composition.

While at the State University of NY at Purchase, I didn’t study photography. Instead I sat in on Jan Groover’s (2) theoretical class. We discussed the photos conceptually and asked questions like: what can an image do, can it activate space? I didn’t understand then a lot of what she was saying, but I stuck with it and listened.

I also studied with John Cohen (3). He had photographed extensively in Peru and done a lot of social documentary. From him I learned to respect the people I photographed. I remembered this when I began using the camera later in life.

III. SOCIAL ASPECT

KA: Could you talk more about social respect and what to consider?

CS: Cohen really taught me the give and take of photography. When you take a picture you have to give something back. You have a responsibility to do the subject justice by representing, showing, and honoring it.

I feel fortunate that I’ve been able to travel all over the world. I’m comfortable with many different people and places. I leave with work while I leave people feeling good about what I’m doing.

IV. INTENTION/SUBJECTS

KA: Can you describe how you relate to your subjects? A photographer has great power when the camera is in hand. What is your intention?

CS: Intention is key. I’ve been with photographers that haven’t worked in public spaces, and I’ve watched their body language and posture. The reality is that when you are unsure, cowering, and hesitating, you’re making your subject nervous.

We are reactive to people’s body language. We may not pay attention to it on a conscious level but it’s there. I approach my subjects with a good heart and pure intention. I feel that they open up more because they can sense it.

V. ALASKA

KA: When you were 30, in exchange for giving up your plane seat from LA to Oakland, Alaska Airlines offered you a flight anywhere. Why did you choose to fly to Alaska and did you intend to photograph ice then?

CS: I wanted to go to Kotzebue, Alaska, where the thought-to-be Bering Land Bridge was. One theory is that people migrated from Asia on the Bering Strait ice bridge during the ice age and populated North and South America.

Theories since then dispute it, but I wanted to check it out myself. I wanted to do a reverse commute (laugh) back towards Russia.

I wanted to experience what it is like to walk onto a frozen ocean.

My luggage was lost when I arrived in Kotzebue. Luckily, indigenous women, working at the airport, clothed me with traditional garb. Their gifts were warmer than what I had packed.

VI. THE LONG WALK

KA: Could you talk about your walk towards Russia?

CS: It was like walking on the moon. My steps were squeaky and I could hear myself breathing. I tucked my camera into my parka.

Every ten feet there was a twig in the ice, as a path. Now and then a snow mobile driver came to ask if I was okay. I said ‘yes, I’m just going for a walk.’

After an hour, there was no traffic. Then, a Russian woman and native man came by and asked me different questions, ‘Where are you going? What do you need?’ I answered, ‘I’m trying to get to where the ice ends and the sea begins.’

Naïvely, I thought that the ice ended next to a blue sea and that I could walk to its very edge. The couple said it was 22 miles farther. I knew I couldn’t walk that far with the -50 windchill and no supplies.

They gave me a ride. The snowmobile went 60mph. After five minutes I asked to stop realizing I’d have to walk back. I turned to see the town. It was gone. Everything was white. No one in the whole world knew where I was.

I began following snowmobile tracks back. It took more than five hours to reach town. On my walk back I had an epiphany, an affirmation of everything I learned through my family as a child. Kinesthetically, I understood I was standing on my planet in space. I understood that everyone is made of the material of this planet.

The idea of tribe and division and language seemed absurd. In that moment I meant nothing in the history of time and space. The snow could blow over my body, and I would mean nothing. But at the same time I could stand there and understand that I was a miracle. So I walked back.

My experience of being connected to the earth inspired my boyfriend’s mother to go on a Russian nuclear powered ice breaker to the north pole. When she came back she invited me to go to Antarctica with her.

VII. SEPTEMBER 11, 2001

KA: So you came back from Alaska and began preparing for your trip to Antarctica, and while waiting for your trip 9/11 happened?

CS: Yes, I had lived in NYC and was a bike messenger. I was very familiar with the World Trade Center buildings. I had taken a picture of the Brooklyn Bridge with the World Trade Center buildings behind it. When the towers came down, I understood for the first time the power of an image as a historic photograph. My photo was proof that the building existed in a way my daughter would never know. It is powerful that a piece of paper is a piece of proof.

A few months later the U.S. attacked another country. I remember sitting on the couch shaking my head. There is so much cynicism and negative thinking. What could I do to counter this hostility, and show there is someone beautiful about life? I want to show the beauty of this planet and how lucky we are to have this place as our home.

KA: How did 9/11 change you?

CS: I became focused. I set personal goals. There was no way that I was going back to an institution to learn what I needed to know. I was almost 33. Instead I sought out photographers who inspired me. If I saw a photo I liked, I’d ask myself how did he or she do that? I’d contact them to ask for help, to show me how they worked and how I could make their techniques part of my practice. Eli Reed, Steve McCurry, and Paul Fusco were all very giving.

VIII. MENTORS

KA: Talk about one of your mentors.

CS: Steve McCurry is my photographic father. He was hard on me. I traveled with him to Tibet and took a bunch of different formats. He saw me photographing in brash light and pulled me into a dimly lit place to photograph villagers. He took the time to show me how light works and how different qualities of light make a real difference.

After I got back from Alaska, I went to Antarctica with my partner and his mother as a family. I remember arriving after all the Steve McCurry portrait work and wondering what I was going to do. There were no people.

So, I decided to photograph everything as if it were a person. It was a strange unintended stroke of genius. My intent was to make a portrait of ice. People intuitively understood this. The ice photos struck a chord. The Antarctica pictures ended up getting shown to an editor at National Geographic.

IX: ANTARCTICA

KA: Did your Antarctica trip inspire your iceberg series?

CS: Yes, the first time I saw an iceberg, my mind struggled to comprehend how this is possible. How did this thing happen? I look at an iceberg and see that this is one snowflake piled on top of another, year after year, until there is an amazing mass. It goes beyond scale that our brains can quantify.

KA: What happened after the National Geographic editor looked are your photos?

CS: I received a National Geographic award which gave me access to another Russian ship. From 2006 to now, I’ve been an expedition photographer in the Arctic and Antarctic environments. I feel privileged to have seen so much beauty. Some days it feels like I’m on a thin veil of what is real and what is a dream.

KA: Has your relationship to icebergs changed conceptually or become political?

CS: In 2007, the UN announced that global warming is happening. When this happened my phone wouldn’t stop ringing.

I didn’t have the intention of being a photo journalist. I took the iceberg photos hoping they would be a historical document. I was trying to create images that would stand the test of time.

Truthfully, almost every single photographed iceberg doesn’t exist as an iceberg anymore.

When I titled this series The Last Iceberg some people were concerned that there was only one left. The story behind the title lies in confusion I had as a child when reading The Last of the Mohicans. I am Shinnecock and we speak Mohegan language. I was upset that this book implied that there were no ‘Mohicans’ and that only one would survive. Clearly, I knew many people who spoke Mohegan.

I understood later that this book was not about my people or one last Mohican. It is about a paradigm shift in America. Things potentially have an end. The book describes how America would no longer be this wild frontier.

It’s similar to our consciousness shift when viewing our polar regions in the light of global warming.

KA: Could you talk more on death and transformation?

CS: I am a big fan of Nick Cave (4), ‘All things move toward their end.’ This is a beautiful quote, but in the wrong hands people read it as death. I don’t think there is real death, but instead transformations into something else.

For example, an iceberg doesn’t die. It ends its existence as an iceberg but becomes water again. This becomes the water that we drink, then sweat, turning into a rain cloud, and then an iceberg again. It’s interconnected and interrelated.

How can we think that we are separate and don’t have a great affect? Each one of us has the potential to create a drop in a pond and create a ripple. As a single it’s just a ripple but if there are many of us we create a wave. There is great power in that and in our ability of consciousness.

Change is the one thing that is truly certain and inevitable. Its time we learn to let go and recognize that we are in servitude to each other.

X. FUTURE

KA: What are you working on now?

CS: I’m editing ten years of images from the Polar Regions. Its reduced to 500 images. I hope to publish it.

My next long term project is chasing storms in the States. It’s the best terrain to do it. I’ve been flying into Oklahoma city and meeting with a meteorologist and hired driver to chase storms.

KA: Photography has taken you on many adventures.

CS: My lifestyle seems glamorous but I also spend a lot of time alone in hotels, getting from one place to the next, and being in the studio. I try to take my daughter with me almost everywhere.

KA: It’s inspiring to see a woman care for a child and still have a vibrant and thriving career in the arts.

CS: Some ask, “how can you leave her for months at a time?” As a women, it would be hypocritical to say go live your dream and be the best that you can, if I’m not willing to do it myself. It’s important for me to lead by example. We have traveled to almost a hundred countries together.

KA: Thank you for your time.

End Notes:

(2) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jan_Groover

(3) http://www.johncohenworks.com/home.html

(4) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nick_Cave

All photos are copyrighted to Camille Seaman.