Location: From New Jersey to California

I. THE CAMOUFLAGE AND CONCEALMENT OF CELLULAR TOWERS

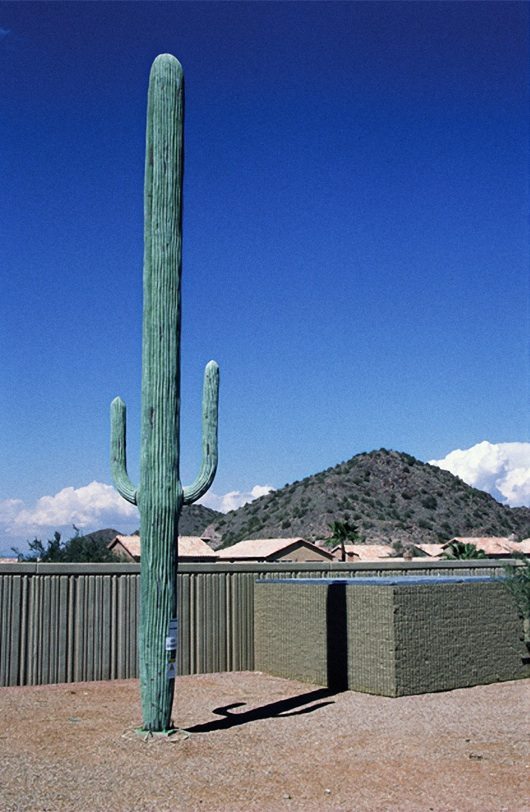

WITH A FLAWLESS BLUE SKY AND HEAT bouncing off its parched desert backdrop an awkwardly straight and unusually tall saguaro cactus conceals a cellular phone tower. These hidden towers, also referred to as stealth cell sites, come in various natural and architectural disguises—palm trees, evergreens, cactus, flag poles, street lamps, church steeples, lighthouses, grain silos, water towers, chimneys, contemporary artworks and clock towers. Faux rocks and boulders have been constructed to house additional electrical equipment. The method of concealment is matched with local scenery or architecture—palm trees in tropical climates, pine trees in the Northwest, and cactus in the desert.

New York-based conceptual artist Betty Beaumont has been documenting these hidden towers since 2004 for her photographic series entitled Camouflaged Cell Concealment Sites. If viewed with a quick passing glance, Beaumont’s photographs could be perceived as portraits of regional communities with fauna and architecture specific to each of their locals. Yet, several of these elicit cause for consternation. Beaumont’s Camouflaged Cells, Sparta, NJ (faux pine) depicts one of the most obviously unnatural towers in the series. The base of this fake pine tree is metallic and cellular antennas are dispersed between its synthetic evergreen branches. Instead of creating an effective disguise, the branches draw additional attention to the tower’s shimmering ‘trunk.’ The cell site is neither a tree nor a lattice tower but instead becomes a hybrid faux evergreen / industrial creation.

Viewed as a series, repetitions reveal even the more effectively camouflaged cell sites. One of these visual similarities is a proportional consistency between elements in the photographs. In addition to soaring columns, the photos contain the necessary sidekick of additional electrical equipment on the ground. Sometimes these equipment sheds are also disguised, but more often than not they sit as nondescript monochromatic cubes next to the gargantuan towers.

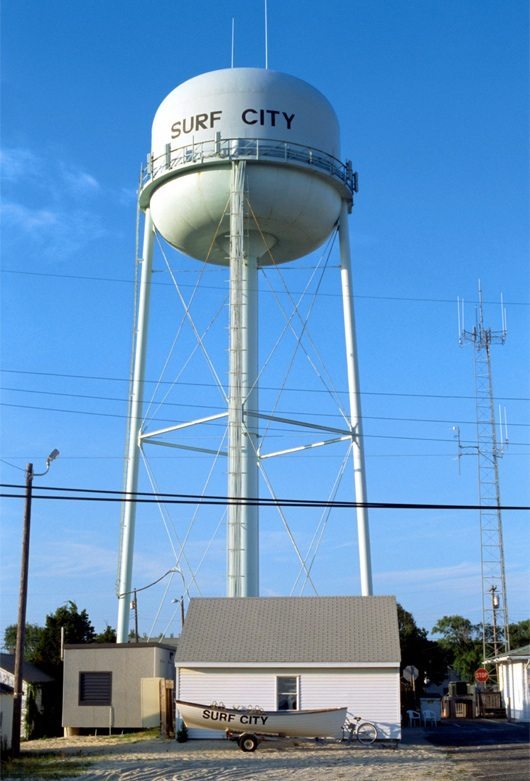

Cell sites that are paired with existing architectural elements are generally less obvious than the faux natural towers. In Beaumont’s Camouflaged Cells, Long Beach Island, NJ (retrofit water tower), a ring of cells lines the walkway around the water tower in the photograph. The water tower is an ideal prefab design to, at the same time, hide cells in plain view and also supply the necessary height for cells and antennas to function optimally. Both the water tower cell and a boat resting on a set of wheels for portability, bear the signage of the town, ‘Surf City.’ Behind the boat is a bike, which one would imagine could be used for a ride along the beach. The picture also depicts an antenna tower in the distance that is not camouflaged. It’s a poignant pairing of resort and leisure objects with signs of industry.

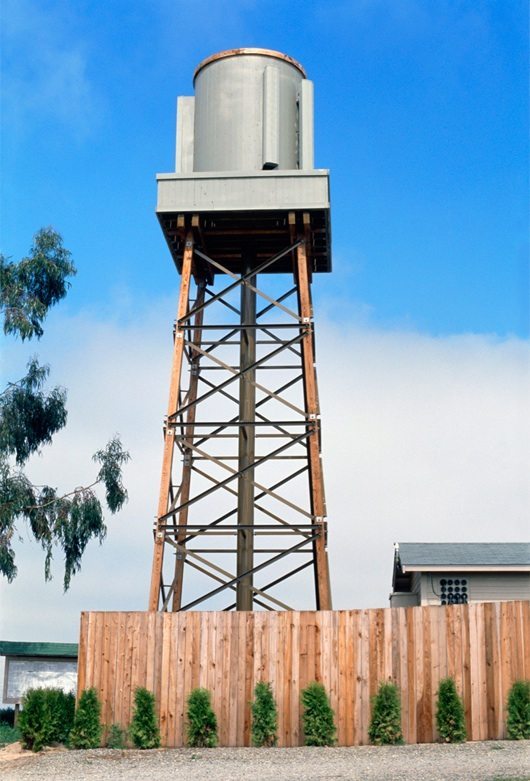

Several photographs in the series invoke a sense of unease when potentially hazardous equipment is supposed to be camouflaged. Even the towers without obviously exposed cells have elements that reveal their true nature. The cactus in Camouflaged Cells, Phoenix, AZ (faux cactus) sports postings adhered to its side—possibly warning of the electrical equipment contained within. Camouflaged Cells, Santa Maria, CA (faux water tower) shows a water tower cell site that seems a bit too pristine to be functional. One would expect this type of structure to have signs of wear or smudges of dirt.

Shifts in scale and unnaturally synthetic components can be dead giveaways for the towers that are hidden in architecture as well as the naturally camouflaged sites. Camouflaged Cells, Phoenix, AZ (cross cluster) features a cluster of three towering crosses adjacent to a church. They do not necessarily look like cell towers, but there is something about their proportions that seems more than a bit off. The crosses are constructed oddly— their white exterior paneling has seams at regular intervals.

Camouflaged Cells, Irvington, CA (faux palm) shows a synthetic monopalm next to natural foliage. While an attempt has been made to hide the cell tower, other reminders of technology are still visible: a telephone pole and electrical lines sit in the background. Two trucks are parked in the foreground to the left of a stack of building materials. The open display of construction supplies is of course not related to the building of the cell tower, but draws attention to these faux natural elements composed of man-made materials.

The photographs are printed in large format. At approximately four by three feet, the framed artworks function less as a window opening onto a landscape, but more as a physical object revealing additional information about each specific neighborhood. They are not overbearing, but instead draw the viewer in for closer observation.

II. THE PROCESS

BEAUMONT’S PROJECT TO DOCUMENT THESE concealed cell sites in the United States began on the East Coast and then jumped to the West Coast. She photographed sites in the NYC metropolitan area, New Jersey, Connecticut, Illinois, Georgia, and Arizona. Beaumont then spent time in California, photographing hidden towers in Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, San Francisco and Berkeley. She also accepted speaking engagements in order to shoot towers in the South and Mid-West. (1)

The research associated with the Camouflaged Cell Concealment Sites series was, by necessity, complicated. Beaumont’s project began early in 2004, a little more than two years after 9/11. Local police forces, perhaps still on high alert for possible security threats, were not forthcoming with information about the locations of stealth towers in their communities. Phone companies would not reveal the locations of hidden towers. Companies that produce disguises for the sites were not responsive to phone calls. When pressed, they would often supply an address for a tower that was not camouflaged. Beaumont did have some luck finding the locations of hidden towers by visiting local fire stations. After speaking with firemen about the project, several not only gave descriptions of how to find the sites, but also supplied Beaumont with hand drawn maps. (2)

The composition of these photographs is very deliberate. In a catalogue description from a recent group exhibition that included a piece from the series, artist, curator, and writer Peter Scott made these observations about the artworks:

Beaumont’s almost deadpan treatment of the towers, photographed straight on and filling the frame, lend her subjects the quality of portraiture, revealing the hidden identity of the transmitting cells that are masked to make this relatively new technology appear green. (3)

In addition to these camouflaged towers being seen as ‘portraits,’ they can also be thought of as reproductions of found objects posturing as sculptures. Close cropping draws attention to the faux natural or architectural elements, encouraging viewers to question why their gaze is directed toward the hidden tower, effectively leading to the deception.

III. COMMUNITY REACTION

IT IS NO SURPRISE THAT THE NUMBER OF CELL sites across the country has risen dramatically in the last 10 years as cell phone usage has increased in popularity. According to the CTIA-The Wireless Association® the number of cell sites in the US in 2010 has reached 253,086. In 2000, there were 104,288 on record, while in 1995 only 22,663 were documented. (4)

The World Health Organization classifies the electromagnetic fields produced by cell phones as possibly carcinogenic. (5) Whether or not cellular towers cause health problems has been difficult to ascertain as mobile phone technology, while in popular use since the 1990’s, is still considered relatively new. Since several cancers do not appear until many years after exposure to a carcinogen, research is still being done to determine the long-term risks of exposure to RF radiation.

While studies have been published that show no link between cellular technology and cancer, other studies have confirmed links to cancer. Popular opinion is that the jury is still out. Studies in Germany and Israel have found a link between cellular towers and increased cancer rates. In a 2007 study, the city of Naila, Germany, found a three times increase of cancer with subjects that lived within 400 meters of cell towers. A Tel Aviv University study in Israel found a four times increased instance of cancer with people living near a cell tower for 3-7 years. (6)

Some cities across the country are trying to pass legislation that would require cellular phone companies to conceal newly constructed cell towers. In 2010, Dustin, FL, proposed an ordinance that would aid in the city’s ability to regulate the placement of towers and the dominance of their visual presence. (7) In El Centro, CA, a cellular tower was hidden in a clock tower. The city required it to be camouflaged due to its placement in a commercial area. (8) Interestingly enough, this is a location that Beaumont has photographed as part of the Camouflaged Cell Concealment Sites series.

O.C. Taylor, a resident of Auburn, CA, lives on the property next to a stealth cell site under construction and has not been placated by attempts to conceal the tower. Lane Kasselman, a spokesman for AT&T mentioned that the project was not yet complete,

‘We are not completely done stealthing the site .We are adding a couple more branches and making it look a little more tree like.’ (9)

The implication here is that the communities’ problem should not be with the proximity of tower to their homes, but instead with the effectiveness of its camouflage.

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 mainly addresses an openly competitive and deregulatory environment for telecommunications companies. It also sets a precedent that allows cell phone providers to argue that constructing a tower is necessary for consistent coverage which should overrule local zoning ordinances. (10) In most cases when there has been a dispute in court over cell phone tower placement in a neighborhood the cellular company has won.

About a fourth of cellular sites across the US are estimated to be camouflaged or hidden. Camouflaging a cell tower can cost up to four times more than a naked cell site. A cell tower in the form of tree can run around $120,000. (11) Income from cell site leases is a big motivator for property owners. The average income from cell sites ranges from $800 – $1500 per month. (12) The allure of added monthly income seems to be of particular interest for organizations such as churches. Sometimes the acquisition of one tower leads to a cluster. In the early 1990’s, Trinity Presbyterian Church, located in Spring Valley, CA, started out with a contract for cell receptors in its roof. Since then, they have put in two additional sites, each generating revenue from a different cell phone provider. One cell site is housed in a faux palm tree and the other in a towering 75-foot cross. (13) The three crosses pictured in Beaumont’s Camouflaged Cells, Phoenix, AZ (faux cactus) also reach a soaring 75 feet. It is sometimes easier to obtain building permits for church properties, as they are already zoned to have tall architectural elements such as towers or steeples.

National parks have also seen a rising number of cellular towers. In 2009, a plan put together by Yellowstone National Park called for a cell tower behind Old Faithful to be concealed on top of a water tower. (14) One of the arguments for having cell towers in the parks is that it allows calls when a hiker gets lost or needs help. As parks and open spaces are often held up as sanctuaries for the preservation of nature, and for people to feel awe and wonder within the natural world, masked technology there seems even more out of place than in residential communities.

IV. REVEALING THE ARTIFICE

SOME COMPANIES THAT MANUFACTURE THE disguises for cell sites also outsource their products, sans cellular equipment, to other venues in need of man-made nature such as zoos or theme parks. There is a visual connection between the look of these synthetic objects used in other locations and camouflaged cell sites. This reference to play or leisure, while possibly unintentional on the part of the companies concealing the towers, sets up a positive emotional link to hidden cell sites.

While not necessarily depicting an object masquerading as something that it’s not, both photographers Luigi Ghirri and Robert Adams have produced images that create tension between nature and manufactured items. Italian photographer and writer Luigi Ghirri (1943-1992) created images that combined landscape, architecture and popular culture. His color photographs represent a conscious observation of representation and the act of viewing. In his work he uses a repeated signage that creates an illusionist space and a distortion of scale. Oftentimes this trickery contrasts figures in front of, but not interacting with, posters displaying idyllic images of nature.

In his work, Robert Adams explores a contradiction between the beauty of the natural landscape, particularly that of the American West, and man-made items. Through his series, What We Bought, Adams’s black-and-white photographs document the sprawl of Denver and its surrounding area in the 1970’s. A photograph in his 1978-1983 series California Dead Palms, Partially Uprooted, Ontario, California (1983) depicts two dead palm trees propped against each other making an ‘x’ across the sky. This picture is the opposite of Beaumont’s photographs of unnaturally perfect cell sites and shows the imperfections of its subject matter, wilted trees leaves and all.

In his 1979 photograph Longmont, Colorado, Adams captures a Ferris wheel rimmed with circles of lights angling diagonally up into the night sky. The Ferris wheel is surrounded by other brightly lit amusement attractions, contrasting starkly with a vast sky and mountain backdrop. The artificial elements in the picture with all their bells and whistles, are not able to compete with the awe-inspiring vista all around them. In his 2008 solo exhibition at David Zwirner Gallery, New York, entitled Forever, The Management of Magic, Belgian painter Luc Tuymans explored the allure of a fabricated experience of wonder with works containing elements from theme parks. He specifically commented on Disney, perhaps the most insidious modern purveyor of ‘magic.’ Despite the media difference between the limited palette paintings of Tuymans and Beaumont’s color photographs, both artists examine the use of artifice.

Several recent exhibitions including After Nature (2008) at the New Museum, New York, NY, Badlands: New Horizons in Landscape (2008-09) at MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA, and La Carte D’Aprés Nature curated by Thomas Demand at Matthew Marks Gallery (2011) have dealt with the intersection of nature and culture. In a current climate of aggressive consumer culture and an increasing level of technologically mediated interaction—connection to the natural world has become increasingly difficult. It is no wonder that artists would be surveying this disconnect.

The title of the group exhibition La Carte D’Aprés Nature, curated by Demand, loosely translates as ‘postcard of nature.’ The moniker is borrowed from a short-lived publication by René Magritte produced between 1951-1954. Three rarely seen paintings by Magritte act as the lynchpin of the exhibition. Combining a healthy dose of reality against illusion with a dash of trompe l’oeil, the compositions of these surrealist works include: a smaller rock over-shadowed by a larger rock, the planet earth resting on a tree limb, and a building in front of a sky breaking apart into cubes. By deconstructing a traditional landscape, the paintings both raise questions of perception and feature the use of imagery that is a hybrid of wilderness and artifice.

Although no actual trickery is employed on Beaumont’s part in her Camouflaged Cell Concealment Sites series, the cell towers themselves have been constructed to use a trompe l’oeil effect. In the case of Magritte, trompe l’oeil is utilized as a means to question one’s perception. In the instance of the stealth towers, trompe l’oeil is used in the tradition of a painted fake wood finish or faux marble countertop—as a deception.

V. LOOKING RIGHT/ LOOKING LEFT

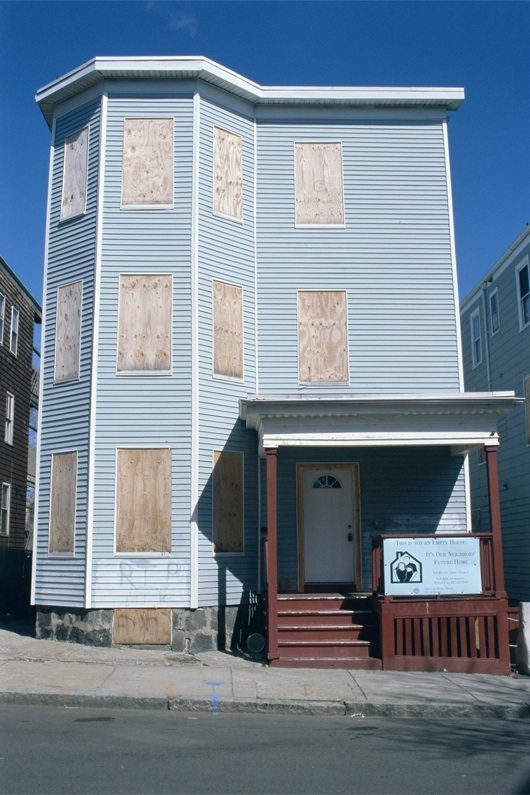

THE CAMOUFLAGED CELL CONCEALMENT SITES series is not the first project by Beaumont to draw attention to socially significant objects hidden in plain sight. The photographic series Love Canal USA (1978) documents the Love Canal neighborhood near Niagara Falls, New York, after President Jimmy Carter declared it a federal disaster area due to man-made causes in 1978. Beaumont’s 2008 photographic series Sub-Prime America presents buildings in Dorchester, Mass. that were foreclosed due to an unregulated mortgage system. And Curtains of Closure, photographed in 2009, shows businesses across the US that have closed due to the economic downturn in 2008 and currently sit vacant.

In 1894 entrepreneur William T. Love began a ‘model industrial city’ lining a canal that linked the Niagara River with Lake Ontario. The canal was later abandoned. In 1947 the canal site was sold to the Hooker Chemicals and Plastics Corporation (now Occidental Chemical). By 1952 Hooker Chemicals and Plastics Co. had disposed of approximately 21,800 tons of chemical waste in the canal. (15) In 1953, the land was sold to the Niagara Falls School Board for $1.00. An elementary school was constructed and the area was developed with hundreds of families building homes in the burgeoning working-class community. In the 1970’s as a result of heavy rain and snowfalls, portions of the landfill began to surface. (16)

By 1978, hundreds of families were ordered to evacuate. The chemical exposure caused burns to children and pets and also resulted in birth defects and miscarriages. (17) In August of 1978, President Jimmy Carter approved emergency financial aid for the neighborhood and New York Governor Hugh Carey announced that state government would purchase the homes of the residents. Purchase offers were made for more than 200 homes costing nearly $7 million. (18)

As the site of one of the worst environmental disasters in the country’s history, images of oozing toxic waste and trauma from evacuation are conjured up. Yet, in her series Love Canal USA Beaumont’s photographs of the abandoned, yet-to-be demolished homes of the community contain an understated elegance. Some of the images show paperwork, presumably connected to the evacuation, on barricaded front doors either still attached or already beginning to be torn away by weather. The homes are boarded-up and vacant, but the architecture of the neighborhood still bears visual reminders of the picturesque American suburb it was meant to be.

The homes photographed as part of Beaumont’s Sub-Prime America series also contain boarded-up windows and signage attached to their facades. One sign reads, ‘This is not an empty house: it’s our neighbor’s future home.’ These homes have been deserted as a result of the economic downturn in 2008, resulting from sub-prime lending practices, rather than environmental disaster. By documenting these homes, Beaumont has created a historical record of the foreclosures and also an archive of their abundance. Despite the disparate reasons for the abandonment of homes in Love Canal USA and Sub-Prime America, each series contains imagery that serves as a monument to socially negative decisions affecting both individuals and their communities at large.

Beaumont’s Curtains of Closure series moves from documenting residential homes to images of vacant storefronts and commercial properties. These photographs taken in 2009 show the effect of the downturn in the economy on local businesses. A few images contain buildings with hung fabric to hide their empty interiors, while other deserted storefronts have their signage and logos covered. This warping and obscuring of text of course does not conceal that the spaces are vacant. In some cases, similar to the Camouflaged Cell Concealment Sites series, attempting to cover up what is underneath actually draws more attention to the object in question.

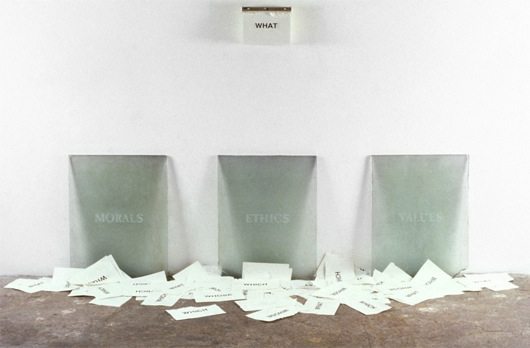

Beaumont’s artistic practice is interdisciplinary; it reaches across a wide variety of media. Her 1989 piece Morals Ethics Values (Whose Which What) is an interactive sculptural installation. Three rectangular pieces of cast glass with a soft green hue sit on the floor, leaning against the wall. Each glass component bears one of three words, MORALS, ETHICS, VALUES. Attached eye-level above the glass sculptures and screwed into the wall is a tear-off book with one word per page: WHOSE, WHAT, WHICH.

The viewer is invited to participate by ripping a page from the book. Throughout the duration of the exhibition of the artwork, numerous pages were torn off and created a pile on the floor. Each page removed from the tear-off book changes which word is visible posted on the wall in relation to the text inscribed on the glass components. The piece either reads: WHOSE—Morals, Ethics, Values; WHAT— Morals, Ethics, Values; or WHICH— Morals, Ethics, Values.

The presentation of the artwork is very straightforward. and the strength of the piece lies in its simplicity. By interacting with the artwork, one is compelled to engage with these words and how they relate to each other. This activity questions both our individual and societal definitions as well as responsibilities to these ideas.

VI. CONCLUSION

THE RATE OF CELL TOWER CONSTRUCTION IN the US will continue to rise. Despite the higher cost of a camouflaged cell site, this trend has held steady in popularity. A shift in focus has occurred to move attention away from the research of potential health risks toward how effectively a cell site can be concealed. Yet, though her photographic series, Camouflaged Cell Concealment Sites, Beaumont documents these hidden towers and brings their presence back into a public discourse.

When they are noticed, stealth cell sites exert an attraction akin to visually similar industrially-created tourist attractions. The hidden sites can be spotted either by their oddly synthetic appearance or how disproportionately they are scaled compared to local architecture or fauna. Stealth cell sites share an aesthetic with a gigantic plastic toy or man-made scenic elements included in an amusement park ride. The visual similarities between hidden cell sites and objects constructed for pleasure or leisure assigns positive emotions to these utilitarian objects.

Beaumont’s photographs serve as a record of these objects; they objectively present their subject matter. Despite the close cropping and centralized framing of the camouflaged cell towers, every photo contains a myriad of details connected to the local life of each community.

As disguises for cell sites become more convincing and common, Beaumont’s photographs will continue to encourage one to stop and take a closer look.

End Notes

1. Email correspondence with Betty Beaumont, August 2011

2. Ibid

3. Scott, Peter. Another Green World, carriage trade, New York, NY, September 22- November 28, 2010 (exhibition catalogue)

4. CTIA.org <http://www.ctia.org/advocacy/research/index.cfm/aid/10323>

5. ‘Electromagnetic fields and public health: mobile phones.’ World Health Organization Fact sheet N°193 June 2011 <http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs193/en/>

6. Serrano, Taraka. ‘Cell Phone Towers: How Far is Safe?’ EMF-Health.com 2007 <http://www.emf-health.com/articles-celltower.htm>

7. Algerin, Matt. ‘Destin wants to camouflage cell towers.’ Florida Freedom Newspapers 14 Nov. 2010 <http://www.nwfdailynews.com/articles/destin-34887-towers-wants.html>

8.Varin, Elizabeth. ‘Camouflaged cell phone tower may rise over downtown El Centro.’ Imperial Valley Press 14 Jan. 2011 < http://articles.ivpressonline.com/2011-01-14/cell-phone-tower_27030264>

9. Jones, Bridget. ‘Resident continues protest against cell tower.’ Auburn Journal 11 Aug. 2011 <http://auburnjournal.com/detail/185210.html>

10. Martin, Susan Lorde. ‘Communications Tower Sitings: The Telecommunications Act of 1996 and the Battle for Community Control.’ Berkeley Technology Law Journal Volume 12 (1997)

11. ‘Cell Phone Towers In Disguise.’ Early Show. CBS. 29 Nov. 2006 <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uRQYan_-CTQ&feature=player_embedded>

12. Kazella, Steve. ‘Cell Tower Lease Rates.’ Cell Phone Towers Blog 7 Aug. 2010

<http://cellphonetowers.wordpress.com/>

13. Sailhamer, Sue. ‘Wireless tower revenue for churches gives new meaning to ‘cell’ group.’ Christian Examiner June 2009 <http://www.christianexaminer.com/Articles/Articles%20Jun09/Art_Jun09_07.html>

14. French, Brett. ‘Yellowstone adjusts cell tower plans.’ Billings Gazette 21 Apr. 2009

<http://billingsgazette.com/news/state-and-regional/wyoming/article_307b3b38-2126-52fb-b462-2ea8350c0fbe.html>

15. Hevesi, Dennis. ‘The Long History of a Toxic-Waste Nightmare.’ New York Times 28 Sept. 1988 <http://www.nytimes.com/1988/09/28/nyregion/the-long-history-of-a-toxic-waste-nightmare.html>

16. Stoss, Frederick W. and Carole Ann Fabian. ‘Love Canal: Reminder of Why We Celebrate Earth Day.’ Issues in Science and Technology Librarianship Spring 2000

<http://www.library.ucsb.edu/istl/00-spring/article2.html>

17. DePalma, Anthony. ‘Love Canal Declared Clean, Ending Toxic Horror.’ New York Times 18 Mar. 2004 <http://www.nytimes.com/2004/03/18/nyregion/love-canal-declared-clean-ending-toxic-horror.html?src=pm>

18. Beck, Eckardt C. ‘The Love Canal Tragedy.’ EPA Journal January 1979

<http://www.epa.gov/aboutepa/history/topics/lovecanal/01.html>

19. Harber, Beth. ‘Public Discourse Connections.’ Binnewater Tides. Volume 8 No. 2, Spring 1991