Steel, textiles, beads, pearls, feather fan

2014

Image courtesy of the artist.

Rina Banerjee, who was born in Kolkata, India and lives in New York, works with a cosmopolitan eclecticism that reflects both her transnational background and her sophisticated understanding of the narrative power of objects. Using trinkets made for the tourist trade — horn, bone, feathers, shells, textiles, glass bottles and antiques — she assembles rapturous sculptures that are mystifyingly shamanistic, yet overflowing with connotation. Her works are hyper-ornamented and lushly seductive. Conjoining rarities with cheap, mass-produced bric-a-brac, she appropriates extravagantly while rejecting hierarchies of material, culture and value.

In Banerjee’s paintings and delicate drawings on paper, female figures float in chimerical landscapes, often in states of transformation or with hybrid features of birds and beasts. Her titles are long, free-form refrains that immerse the viewer in the physical and emotional space of the work, heightening its quasi-mystical magnetism.

In a 2011 feature in Artforum, Banerjee describes the foundations of her work:

My mother told me that my first name is special because it is not typical in India—it is spelled differently. Hence, I was free to be what I wanted, or so I presumed. I was born in Calcutta, but I grew up in London and, then, New York, where I now live. Growing up abroad [as we called it] was a strange experience in the 1960s; there were so few Indians in the West. My parents saw themselves as international citizens. Maybe they imagined a future that we are just beginning to glimpse. I dream of this willingness to close the gaps between cultures, communities, and places. I think of identity as inherently foreign; of heritage as something that leaks away from the concept of home—as happens when one first migrates. Even my interest in science embodies an awareness of other worlds, worlds that coexist with us, but which we cannot experience or know. The sky, the stars, and the earth contain so much more than we think.

Freedom is the most expensive commodity; nature the most dangerous beauty. My work examines both. My art depicts a delicate world that is also aggressive, tangled, manipulated, fragile, and very, very dense.

fans, feathers, cowrie shells, resin alligator skull, globe, glass vials, light bulbs, gourds, steel wire, Japanese mosquito nets

90x253x90”

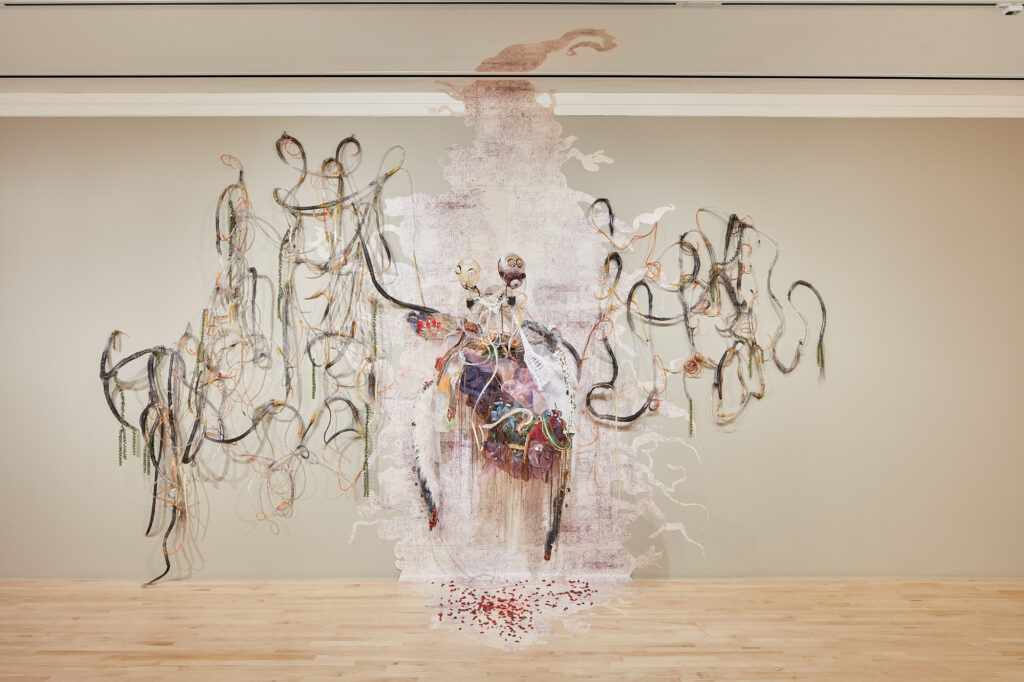

Installation view of Rina Banerjee: Make Me a Summary of the World at San José Museum of Art, May 16–October 6, 2019. Photo by J. Arnold, Impart Photography.

Kumkum, turmeric, Indian blouse gauze, fake fingernails and eyelashes, foam, feathers, fabric, Spanish moss, light bulbs, wax, quilting pins, plastic tubing, latex and rubber gloves, acrylic and dry pigment, cowrie shells, gourd, horn, urchins, silk, bone

Installation view of Rina Banerjee: Make Me a Summary of the World at San José Museum of Art, May 16–October 6, 2019. Photo by J. Arnold, Impart Photography.

Wood rhino, Chinese umbrellas, sea sponges, linen, beads, pewter soldiers, grape vines, glass chandelier drops, acrylic horns, wire, nylon and bead flowers, 7 × 4 ft.

Installation view of Rina Banerjee: Make Me a Summary of the World at San José Museum of Art, May 16–October 6, 2019. Photo by J. Arnold, Impart Photography.

Black synthetic horns, wire, netting, lightbulbs, scale, ostrich eggs, textiles, cowrie shells, pebbles, coins, feathers, fish vertebrae, greenery, coral, glass birds, miniature human and animal figurines, plastic cups, and red thread,

132 x 234 x 128 in. 2013

Installation view of Rina Banerjee: Make Me a Summary of the World at San José Museum of Art, May 16–October 6, 2019. Photo by J. Arnold, Impart Photography.

Beads, shells, fabric, metal, mirrors, plastic, thread

119,4 × 39,4 × 34,3 cm

Image courtesy of the artist.

mice was eaten by a world hungry for commerce made these into flower, disguised could be savoured alongside whitened rice

Oyster shells, fish bone, thread, cowrie shells, fur, deity eyes, copper trim, ostrich egg, epoxy American buffalo horns, steel, fabricated umbrella structure, steel stand, pigeon-feather fans, 21⅝ × 61 × 78⅜ in., 2009, Installation view Fowler Museum at UCLA

Installation view of Rina Banerjee: Make Me a Summary of the World at San José Museum of Art, May 16–October 6, 2019. Photo by J. Arnold, Impart Photography.

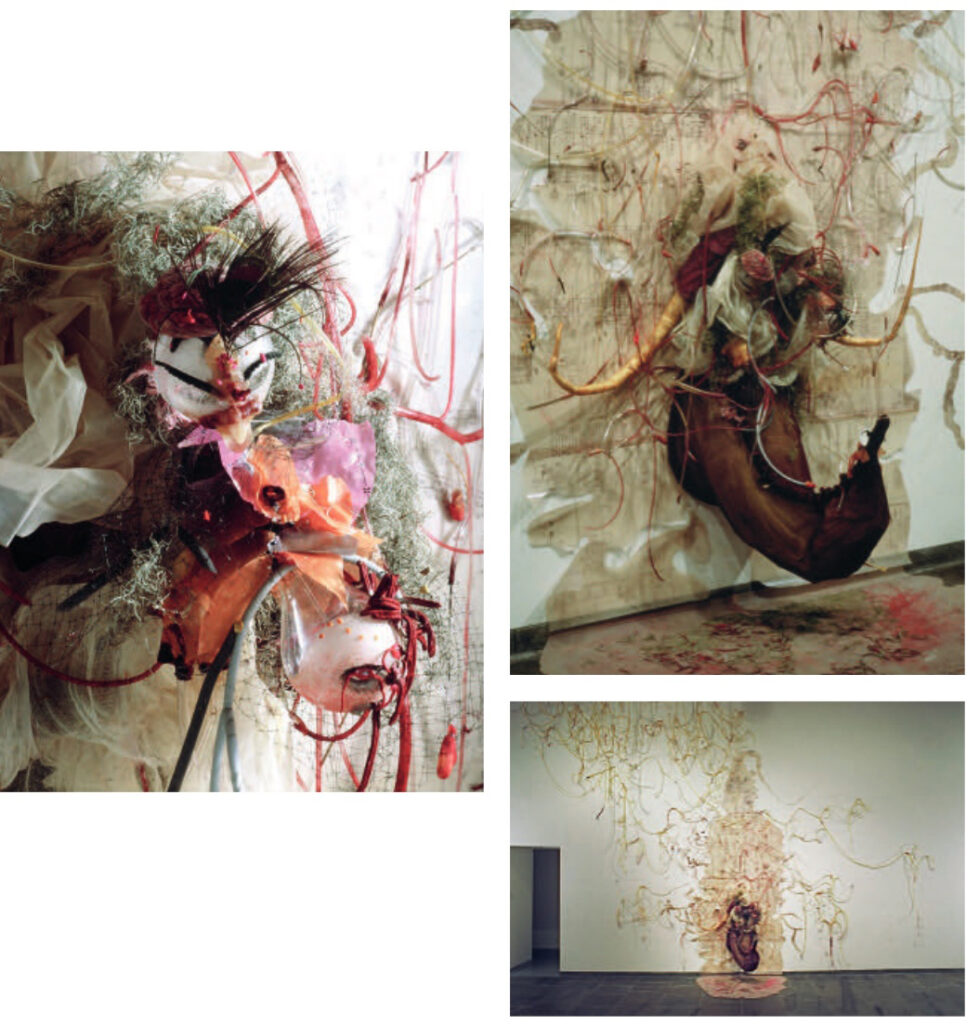

Incense sticks, Kumkum, vaseline, turmeric, Indian blouse gauze, fake fingernails and eyelashes, chalk, foam, feathers, fabric, Spanish moss, light bulbs, wax, Silly Putty, quilting pins, plastic tubing, latex and rubber gloves, acrylic and dry pigments, dimensions variable. Installation: The Whitney Biennial 2000, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 2000

Images courtesy of San José Museum of Art

Incense sticks, kumkum, vaseline, turmeric, Indian blouse gauze, fake fingernails and eyelashes, chalk, foam, feathers, fabric, Spanish moss, light bulbs, wax, Silly Putty, quilting pins, plastic tubing, clay, latex and rubber gloves, acrylic and dry pigment

Dimensions Variable

Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin Gallery

The production of the Contagious Migrations originally began in 2000 with an older iteration of the sculpture titled Infectious Migrations, which was part of the 2000 Whitney Biennial. Originally conceived in the aftermath of the AIDS crisis, the piece critiques the construction of a disease-ridden ‘other,’ and the intercorrelation of illness with systemic oppressions, such as homophobia, racism, and xenophobia.

The background of the piece is composed of found hand-drawn exhaust and ventilation maps from the Columbia University Center of Disease and Control from 1968, and points to another historical moment in which fear of disease was imbued with systemic oppression. 1968 was a year of a flu pandemic in the United States, which was caused by a flu strain derived from China and led to a surge of racism and violence toward East Asian peoples.

The piece is ripe with medical residue: plastic tubing, latex and rubber gloves. The tubing underscores the phenomena of transmission, referencing both the transmission of medicines, as well as the global movement of people, goods, and disease via colonization, enslavement, immigration, or trade. The piece also contains elements of or associated with the human body such as fake fingernails and eyelashes, highlighting the human beings impacted by both disease and persecution.