Location: Sussex, UK

I. BACKGROUND

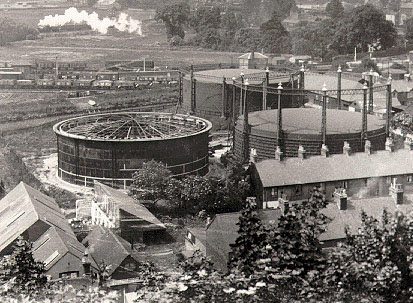

IN THE TOWN OF LEWES in East Sussex, UK, there is a piece of wetland sandwiched between the river and the town, which 50 years ago used to be industrial land – a major railway marshalling yard– and which now due to the dismantling of the railway line in the ’60s has reverted to wild scrubland. At some point the land was saved from development by the creation of a small local nature reserve managed by the Lewes Railway Land Wildlife Trust. The land is both wetland and woodland, has a natural spring running through it and is overlooked by a steep hill on the far side of the river Ouse.

II. PLANNING HEART OF REEDS

IN 1998 THE TRUST WERE planning on increasing the biodiversity of a part of the land by creating a reed bed, but were struggling to find the funds to do it. In January of that year the river flooded, and as I stood on the hill overlooking the land, I noticed that the scrub grasses poking through the flood water formed a kind of pattern. I realised then that if you planted reeds in a pattern you would get a drawing on the land visible from the hill. Excited by this idea, I took some drawings to the trust and suggested that if they let me design the reed bed, we might pull in arts lottery funding to create their biodiversity. The trust agreed if I would work in close collaboration with them and that we do it in three stages:

- Design and consult with Trust and the public

- Fund raise for the construction, education, website etc

- Fabrication.

III. PHASE ONE

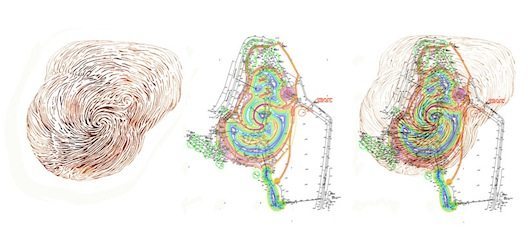

FOR PHASE ONE WE WERE ABLE to use some money given to the town for the making of public sculpture, and I worked closely with environmental scientists and Lewes District Council who owned the land and oversaw the project. The finished design with model and plans were exhibited in the town in 2000 and comments sought. Ultimately we had overall support. It then took 5 years to raise the money from charitable sources and Arts lottery. The work was excavated in 2004 and opened in 2005. It took a further three years for the reeds, planted a metre apart to become fully established.

Heart of Reeds is a dynamic living sculpture. Its purpose was to increase the biodiversity of the Railway Land by creating a reed bed. The idea therefore was that it should be visible as a pattern from within the work and from adjacent Chapel Hill, and that in the microcosm it should provide habitat for as diverse a range of species as possible. Biodiversity tends to occur at the borderlands– in this case between water and land– so a complex pattern of islands was what was needed. The pattern had to be both relevant and practical.

IV. DESIGNING HEART OF REEDS

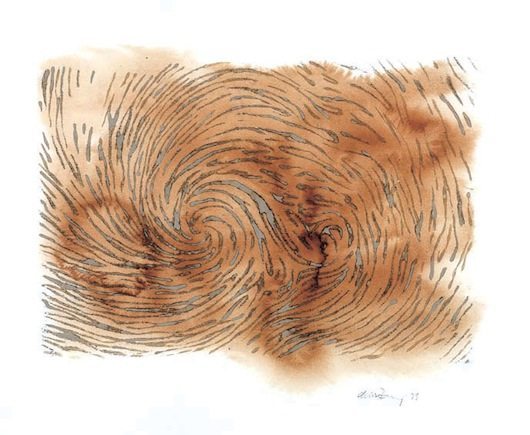

BLOOD FLOW IN THE HEART IS a complex system. The heart pumps blood in a twisting motion – like wringing out a wet towel. This is known in medical terms as a Cardiac Twist. The fibres of the heart muscle are arranged in a helix pattern so in a cross section at the apex, these fibres look like a double vortex, the same pattern you get in river flow, weather systems and even the formation of galaxies. It is in effect energy made visible.

Simplified, this was the pattern that was chosen. Emotionally it went to the heart of the matter and practically it allowed for a series of twisting islands. Its form also has two chambers or ventricles, enabling the reed bed to be divided into two halves with sluice gates (valves) for clearing detritus, one side at a time, and also to allow for raising and lowering of water levels and to flush spring water through the whole sculpture.

V. THE COMMUNITY

THE COMPLEXITY OF BOTH AN ecosystem and blood flow in the heart follows the same laws of nature. Complexity Theory proposes that as a system becomes more complex, instead of tipping into chaos, it tends to create coherent patterns. This can apply to a natural system like a reed bed as well as a human system like a city or corporation.

When Heart of Reeds was first created in 2004 every kind of creature appeared in both the water and on land, but slowly with time, things have evened out into a coherent pattern. Darwin predicted how this happens in an elegant experiment on his lawn, where he removed a yard of turf and observed the subsequent colonisation by various species of plants over a period of years. The community of Lewes’ relationship to the Railway Land, facilitated by the RLWT, could also be seen as an evolving system.

VI. MANAGING HEART OF REEDS

THE DESIGN WAS THE RESULT OF many conversations about biodiversity and the practicalities of managing a semi- natural system. During the construction, nothing apart from reeds was added and nothing removed. The Railway Land is industrial land reverting to wild. It can never be a totally natural system because the river which created the flood plain has been canalised. This means that what a wild river would naturally do in scouring the wetland in annual flooding now has to be managed by man. But this is the reality of our world; we too are nature and play a part in all natural systems.

Heart of Reeds has been designed to facilitate scouring of detritus on a 5 -7 year cycle, without destroying the species which have colonised it. It is managed, not as a work of art but only to maximise biodiversity; so there is an element of human choice in this.

VII. A LIVING SCULPTURE

HOWEVER, AS A WORK OF ART THIS is a living, changing, complex dynamic sculpture. In the summer it is a wild and seemingly chaotic organism. In the winter, as plants die back, the bones of the sculpture are re-revealed. With the changing seasons and weather, in both the microcosm and the macrocosm, Heart of Reeds reveals something different every day. Eight years on it continues to thrive, and is much used by both people and wildlife.