In This Issue

-

Jourdan Imani Keith ● Your Body

-

Jackie Brookner ● Valuing Dirt + Water

-

Stacy Levy ● Working Earthworks

-

Daniela Corvillon ● Wastewater In Cuba

-

Linda Weintraub ● Tragedy of Wild Waters

-

Chris Drury ● Heart of Reeds

-

Betsy Damon ● 25 Years On Water

-

Basia Irland ● The Ecology Of Reverence

-

Suzon Fuks ● Waterwheel, Women & Collaboration

-

Susan Leibovitz Steinman ● DIRTY WATER

WEAD ARTISTS PORTFOLIO

This issue inaugurates the first WEAD Magazine Artists’ Portfolio. Open only to WEAD listing artists and members, each Portfolio is curated by the Editorial Committee to showcase artists whose work reflects diverse approaches to the issue’s theme. Here they respond to ‘Dirty Water.’

ARTISTS

Fereshteh Alamshah

Navot Altaf

Liza Behrendt

Christina Bertera

Erika Fielder

Michele Guieu

Keti Haliori

Patricia Johanson

Sant Khalsa

Bobbi Mastrangelo

dominique mazeaud

Perdita Phillips

Aviva Rahmani

Rulan Tangen

Shai Zakai

Humans, fish, trees, water, river, wind, and sun are all from the same chain. Humans are a very powerful link and can protect or destroy the chain.

Humans, fish, trees, water, river, wind, and sun are all from the same chain. Humans are a very powerful link and can protect or destroy the chain.

Humans and fish are metaphors for nature while the plastic symbolizes the polluters. No matter which element of the chain gets contaminated each link will eventually be infected.

I enjoy the feeling of performing and integrating with nature. The audience of my performances also experiences this unity. It is an immediate recognition of the anxiety, fear, joy and the ecstasy of nature.

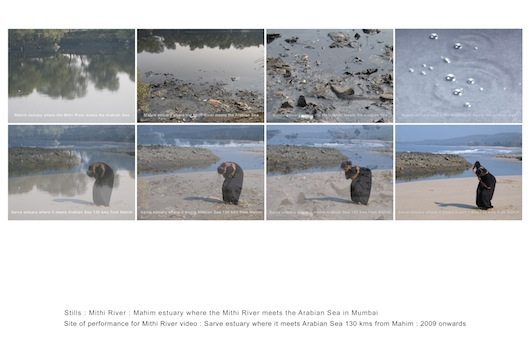

From its Origin in Borivali Park, 18 km long Mithi River and its tributaries flow through the suburbs of Mumbai and finally merge in Arabian Sea in Mahim . The irony is that more than half or 1000 acres of the most important part of the Mithi in estuary has been reclaimed by Bandra-Kurla complex and recent Worli-Bandra sea link project. The river is compelled to flow like a gutter by putting ‘bund’ on its sides through the estuaries which is against the basic characteristics of estuaries – These atrocities on Mithi River, which nourished the people for hundreds of years along the banks, have destroyed the work pattern and the soul of the mother river. This estuary which was the kidney and lung of the city cannot perform its role. It cannot accommodate the rainfall as well as the tides of the sea – hence the stability and protection of the shoreline is ‘LOST’ This buffer from many angles in between island city and its suburbs had to perform life saving role for Mumbai . The question is how far a man will be able to disturb nature’s plan and to what extent nature responds to man’s interference in her plan ? State of Mithi River made me understand ‘Occurrence of design in nature, and how we design devices for human use’. According to Constructal law ‘design in nature is flow Not all changes are improvements, but those that stick measurably enhance flow. It applies to the river deltas, arteries and veins of our bodies and tree branches Everything that moves, whether animate or inanimate is a flow system It defines what life means’.

On the shores of the Bharathapuzha in Kerala, India, where indiscriminate sand mining is among the threats to life of this 130-mile river and its adjacent communities, Beauty of Water offered a painting camp from June 26-28, 2009. Camp director Baiju Laxman and a dozen local artists painted on the theme of appreciation for water. The camp was held at the ancestral home of host Udayashankar. With a sense of adventure and experimentation, and artistic guidance from P.S. Radhakrishnan, we collaboratively created an abstract composition on one canvas, shown here. Beauty of Water was founded in 2006 by Liza Behrendt.

EMBRACING OUR PLACE IN THE NUTRIENT CYCLE,

porcelain, plywood, found metal, plant material, Corian, flex hose, 2007.

Human urine is wreaking havoc in waterways around the world– creating “dirty” water that is uninhabitable for many beings. The nitrogen and phosphorus in urine are difficult for treatment plants to fully remove. When released into rivers, lakes, and estuaries, they cause algal bloom and dead zones.

Urine separation at source is being promoted worldwide by a variety of organizations as a way to capture the nutrients from our human ‘effluent’ and avoid polluting our waters. Phosphorus in particular can be returned to the soil rather than lost in dilution to vast bodies of water. (With peak phosphorus looming the extraction of phosphorus from wastewater will become more and more of a priority.)

This ‘prototype’ urine separating compost toilet seat suggests that our toilet could be a ‘sculptural destination point’ while reminding us that we too are part of the grand cycle: what comes in goes out, back around, and in again through our food. Or in this case, through a flower that graces the vase at the rear of the seat.

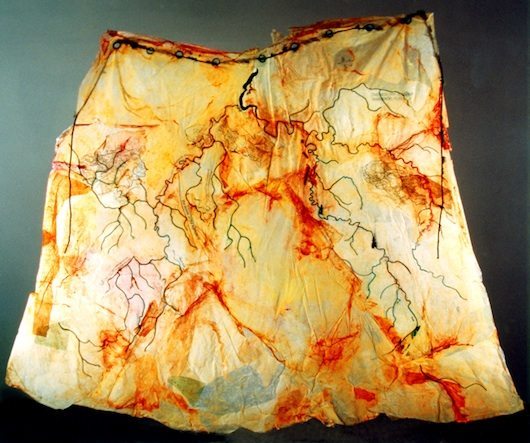

What does it mean to wear one’s own watershed like a cape? How does our watershed reside within us? The fluids within our bodies are replaced within 7 days of drinking from our home tap. We thus become a tributary of our watershed’s stream. Where does our section of stream go? What conscious gestures of return to our watershed do we perform each day? Where is your watershed? Are you a tributary?

Granted just won the best Environmental Award at the SF Bay Area Women in Film and Media (BAWIFM) Short Film festival 2013.

Abundance of clean water is not everywhere. Even in California where I live there are water problems, but compared with places where people do not even have access to clean water, we are spoiled and we take it for granted. We do not have to go fetch your clean water every day. It is something we simply do not think about. When I lived in Senegal in Africa, I was amazed to very often see lines of women walking to get some clean water and take it back home. It is a sight I never forgot. Water is the most precious liquid we have on our planet and having access to clean water should be a basic right for any human being.

The “World Water Museum” installation by Keti Haliori focuses to alert people on the challenges of clear, potable water on the planet. It approaches surrealistically the vast environmental problem, presenting water as “museum item”. The installation is constructed gradually through the participations of volunteers who send samples from rivers and lakes. The samples are chemically analysed, therefore each one gets a profile of physical characteristics and afterwards are safely kept in laboratory vials. A portion of each sample is mixed with portions of all the others, in a separate vessel, and sample by sample is increased the “Earth’s Water” level.

Thirst http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I4SvYc7pxm0

Ilissos River http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FEu4ZD1A4nE&feature=related

“I am currently working with Carollo Engineers on a new $140 million dollar water recycling facility for the city of Petaluma, California. The project includes oxidation ponds, sewage treatment wetlands, and polishing ponds for the removal of heavy metals, as well as a new 272-acre tidal marsh and mudflat, PETALUMA WETLANDS PARK. As a designer I have always been interested in enmeshing human needs within the larger patterns and purposes of nature. In Petaluma, art and infrastructure, ecological nature and the public landscape, are unified within the image of one of the area’s smallest inhabitants– the “Salt Marsh Harvest Mouse”. More than three miles of public trails and interpretive sites trace the patterns of the creature, while revealing the intricacies of wastewater treatment, the tidal cycle, ever-changing patterns of land and water, and the complex relationships between microhabitats and ecosystems.

http://patriciajohanson.com/timeline/ellis_creek_petaluma.html

The Santa Ana River is the life source that nourishes the earth and every living cell in my community. I have photographed the 96-mile-long Santa Ana River and its expansive watershed for nearly three decades. The photographs create a contemplative space where one may sense the subtle and profound connections between themselves, the natural world and our constructed settings. My work addresses complex environmental and societal issues and reflects upon my ideas concerning my/our relationship with the river — as place of community, economic resource, natural habitat, sanctuary, and both source of life and destruction.

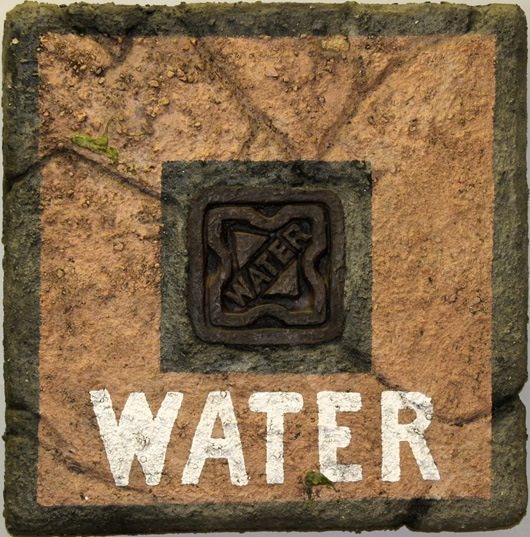

‘Grate Works:’ transformations of manhole covers, sewers and grates into wall relief street-scapes and embossments on hand made papers. The message of her manhole art is to conserve and protect our precious resources.

In 1979, I knew that my calling was to find the spiritual in art. The Santa Fe river, a tributary of the Rio Grande, initiated me. ‘The Great Cleansing of the Rio Grande,’ a seven-year monthly ritual performance taught me that there was no separation between art and life. My story: walking, cleaning the river, speaking on her behalf through various projects over the years… basically listening. Like all rivers, the Rio Grande is the clearest of teachers; one of many rivers that form a web encircling the Earth with life and love. In 1986, my heart broke when I saw what was happening to the Earth. Today I am a heartist, walking in meditation with the waters of the Earth.

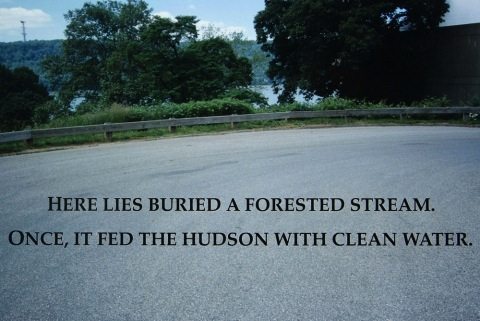

SINAGE, Installation detail from “Through the Glass Darkly” for “Imaging the River” 2003- 2004 at the Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, New York.

Rahmani’s current work reflects her interest in the application of mapping analysis, to “explore potential solutions for urban and rural water degradation in large landscapes.” Rahmani has taught, lectured and performed internationally, and is the recipient of numerous grants and fellowships including two from the Nancy H. Gray Foundation for Art in the Environment in 1999 and 2000.

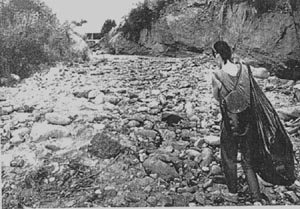

DANCING EARTH’s performance – WALKING AT THE EDGE OF WATER – is an inter-tribal contemporary dance expression of Indigenous water perspectives. Every creative aspect of this eco-production reflects cultural and environmental worldview, with Indigenous collaborators in movement, musical composition, language, video imagery, costume and visual art. This work is motivated by the urgings of Native grandmothers and invokes powerfully relevant water themes of creation, destruction and renewal. WALKING AT THE EDGE OF WATER parallels ancestral healing rituals in a dance of inter-disciplinary Native expressions that is both primal and futuristic.