Location: Rhinebeck, New York

INTRODUCTION

WATER HAS A SPLIT personality. On the one hand, it is gregarious, continually absorbing and dissolving other materials. Water’s remarkable versatility is epitomized by its capacity to dissolve both acids and bases. On the other hand, it is meddlesome, actively seeping into the tiniest crevices of the Earth and permeating the greatest expanses of the atmosphere. Its all-powerful influence on Earth’s conditions is exemplified by its ability to transport any particle or chemical it encounters throughout the globe. Thus, on the one hand, water serves as an agent for cleansing, purifying, protecting, synthesizing, nourishing, combusting, and delighting. It is the unique liquid that enables life and is essential for health and vitality. However, water also transmits death, disease, and deformity. Thus, water shortages are not the only cause of stress on humans, plants, animals, insects, and bacteria. They are at risk even in regions of the globe with access to water. According to a UNESCO report, ‘Water-related diseases are among the most common causes of illness and death, affecting mainly the poor in developing countries. They kill more than 5 million people every year, more than ten times the number killed in wars. These diseases can be divided into four categories: water-borne, water-based, water-related, and water-scarce diseases.”

The massive scale of squandering and abuse by humans has stripped water of its powers to heal and nourish. Once honored as the sacred source of creation among the ancient Babylonians, Pima Indians, Hebrews, Greeks, Aztecs, Egyptians, East Indians, Chinese, etc., the waters that course through contemporary lives has either been demoted to a formless, colorless, tasteless, and odorless liquid that flows predictably from a tap, or it looms into consciousness as a fearsome toxic menace. An arsenal of purifying treatments has been developed to decontaminate this former symbol of purity. They include filters, ultraviolet zappers, ionization, chlorination, etc.

Joseph Beuys addressed humanity’s skewed relationship with the Earth’s waters in a 1971 when he performed ‘Bog Action.’ The performance survives as a photograph depicting Beuys, fully clothed in his signature thick-soled shoes, dark slacks, white shirt, and felt hat, leaping joyfully into a murky brown bog. It requires no stretch of the imagination to realize why the word ‘bog’ is slang for ‘toilet’ in Britain. The squeamish ‘Yuk!’ response is evoked because the thick, brown, boggy waters, that consist of decaying plant and animal matter, resembles the contents of a toilet. Beuys’s blissful leap reveals a contrasting attitude. To Beuys, the wetland was misjudged, maligned because it did not conform to aesthetic measures of beauty. But it functioned beautifully by maintaining the ecological health of the watershed. His immersion honored the valuable role that bog waters play in producing oxygen, sinking carbon, cleansing water, producing organic molecules, and supporting diverse plant and animal organisms.

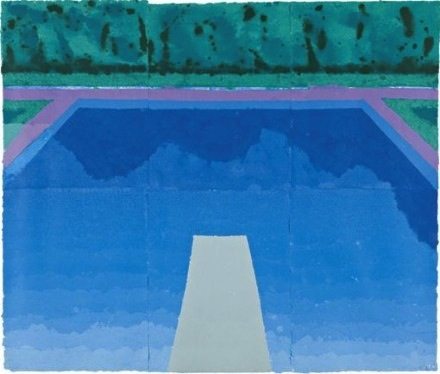

The public’s squeamishness regarding natural bodies of water factor into David Hockney’s popularity. Hockney earned renown in the 1970s by creating paintings depicting sylvan swimming pools, not ponds, lakes, or bogs. The water in these paintings is crystal-clear and cobalt-blue. It not only accounts for each painting’s visual appeal, it reinforces viewers’ preferences for water that is a product of engineering, not nature. Pool water is pumped through filters, treated with chemicals, and otherwise sterilized to remove the forms of organic matter that Beuys relished in the bog. It seems that the water that is desired today is ‘treated’ and ‘domesticated’, not ‘natural’ and ‘wild’. The waters in Hockney’s renowned paintings are stripped of their sacred power to foster health and growth. These works of art epitomize an era in which natural bodies of water are suspected of containing unsavory concoctions of effluents from sewage and industrial processes, and teeming with unidentified populations of micro organisms.

Each of the works of art discussed in the accompanying essays reveals a particular contemporary water calamity. Tainted water that falls as acid rain in Nigeria is the topic of Bright Ugochukwu Eke’s community project. A severe water shortage in Australia inspired Gerda Steiner and Jorg Lenzlinger’s mournful installation. The engineered social and environmental atrocity known as the Great Gorges Dam in China is lamented in a narrative scroll by Yun-Fei Ji. Together, they explore the theme of water in terms of lack, excess, and mismanagement, all reasons why distress now accompanies such elemental functions as drinking and bathing for many people across the globe.3

Before embarking on these disturbing narratives of abuse, let us pause to take note of water’s remarkable attributes as a precious resource:

– Water distributes the substances that it dissolves or suspends.

– Water erodes, etches, and carves hard substances.

– Water conducts heat.

– Water cleans by dissolving loosely bonded compounds.

– Water softens many materials.

– Water evaporates, condenses, freezes.

– Water creates clouds, fog, rain, snow, mist, dew, sleet, hail, flood, etc.

– Water flows downward due to gravity and it creeps upward due to capillary action.

– Water is the habitat that supports the greatest concentrations of species.

– Water cleanses and uplifts the spirit.

– Water is essential for life.

– Water can kill.

I. BRIGHT UGOCHUKWU EKE – ACID RAIN CHECK

Born 1976, Nsukka. Nigeria

THE NIGERIAN ARTIST Bright Ugochukwu Eke laments the wholesale corruption of much of the planet’s waters which are endangering life and sabotaging water’s time-honored role as an embodiment of life, birth, and renewal. He asks, ‘How do we understand ourselves? I thought of a common language in nature. Water is a precious natural medium/resource with a universal language. It occupies the largest part of the earth, but has been disrespected, polluted, and contaminated with the advent of industrialization. It has been forced to lose its spirituality and purity.’5

Eke sought a way to translate his lament into the language of art. He explains his dilemma,

‘All the actions of water pose problems to man and society. How can my expressive engagement deal with these problems? So in trying to come to terms with some of these questions, I have to think of what man has done to water, what water has done to man. That led me to question the relationship between man and the environment. I see water as a water medium with a water language. I thought it would be necessary to use water as a metaphor to articulate my ideas about man’s relationships. I’m using a small part to talk about a whole phenomenon, of which one is acid rain.’6

Rainwater becomes noxious when water molecules dissolve acid particulates in the air. The particles originate from effluents emitted from factories, waste treatment plants, automobiles, fertilizers, and pesticides. They fall back to earth as acid rain. These events instigate a litany of environmental woes that include deforestation, reduced soil fertility respiratory and skin diseases, and ecosystems that can no longer support biological diversity. Most alarmingly, acid rain poisons drinking water. Just at a time when population growth is increasing the demand for potable water (which normally amounts to only 1% of the Earth’s total water store), acid rain is causing supplies of this essential liquid to shrink.7

Eke narrowed the aperture of his perception and attended to a single location (his homeland, Nigeria), a single water hazard (acid rain), a single jeopardy (contaminated drinking water), a single culprit (petroleum refineries), and a single indicator of the problem (packaged potable water).

A personal experience in Port Harcourt, a major industrial center in Nigeria, provides evidence of this regrettable state of affairs. He explains, ‘I was working outside in the rain. In two days I discovered skin irritation from toxic chemicals that go into the atmosphere from the industry. The emissions from the industry come down when it rains. I was not surprised as Port Harcourt has a lot of industries, especially in manufacturing and oil production. Then I came to think about not just myself, but the people who live in the area. What about the aquatic life? What about the vegetation?’8

Eke had this experience in the delta of the Niger River in Nigeria, which is blessed with abundant fresh waters that support one of the highest concentrations of biodiversity on the planet. Yet these waters are now among the most contaminated, due in large measure to the fact that the region is also rich in oil. Since 1958, the petroleum industry has accounted for more than 90 percent of the nation’s total export.9 In Nigeria, productivity and contamination are linked because the country does not have a pollution control policy. There is nothing to prevent oil companies from spilling oil (which pollutes groundwater), and burning natural gas flares (which contaminates the atmosphere). Acid rain is so severe that the shelf life of the corrugated iron sheets used for roofing in most Nigerian villages has decreased from twenty years to five.10

Runoffs from petroleum processing and petrochemical plants dump tons of toxic wastes into nearby waters. This problem is compounded because few regions in Nigeria have ‘pipe-borne water’ that is treated. As a result, even the very poor who live in this rain-rich country must purchase drinking water. Throughout Nigeria, thousands of water vendors push heavy water carts around the rutted streets to sell water. It costs consumers approximately $480/year, a sum that is far greater than the cost of water in advanced countries.11 But even these waters may not be safe. Some water vendors sell surface water from scummy rivulets that may contain sewage. Others get their water by drilling boreholes that, in areas of mining and oil drilling activities, is often contaminated.

In Nigeria, both surface water and borehole water is packaged in cheap plastic bags called ‘sachets’. A disconcerting paradox emerges from this container because it is the petroleum industry’s negligence that makes the manufacture and purchase of these bags a necessity for survival. These bags are made of petroleum-based plastic! Ironically, drinking packaged water intensifies the demand for petroleum, which increases petroleum production exacerbating acid rain and groundwater contamination. As a result, the industry profits from the worsening the conditions that require water to be packaged.

Eke identifies yet another aspect of this troubling scenario by commenting, ‘The problem is that people buy the water in plastic bags and after use they throw them away and they become litter in the environment. You find plastic bags all over the place.’12 Besides being unsightly, discarded plastic bags pose a serious and enduring hazard to wildlife. Most plastic bags take centuries to decompose. They break down into toxic particles that mix with soil and endanger the food chain.

The proliferation of discarded sachet bags provided Eke with a compelling medium for conveying Nigeria’s water crisis through art. He and assistants gathered thousands of sachet water bags from the littered streets to create Shields (2005/06). The bags appear in this an installation in their soiled states so viewers can discern their source as discarded waste, which is familiar to them. At the same time, he contrived a way to present the sachet bags to convey the environmental perils they pose and the culprits responsible for this water plight. Eke explains how he accomplished these twin goals. ‘Now we need something that stops the same water from going in. So I picked up some plastic water bags and made out of these raincoats and umbrellas.’13 The work’s title, Shields, dramatizes the need to protect the body against the dangers of rain that is laden with hazardous acids instead of healthful nutrients.

The rain gear was fabricated by tearing the sachet bags open and laying them flat so they could be ironed together along the edges. The resulting sheets of plastic were then cut and assembled into raincoats and umbrellas. The coats are long, hooded, unfitted, and unembellished. Stripped-down in this manner, they announce to viewers that the reason for their existence is exclusively functional. They reference emergency survival gear, not fashion or commerce.

The scale of the installation was determined by the scale of the water crisis it conveyed – both are large! 120 coats and 60 umbrellas filled the exhibition space to its limit, indicating that the enormity of the toxic effects of acidified rainwater. When the work premiered in Senegal, the raincoats were suspended from the ceiling and hung on the walls of the gallery. The umbrellas were scattered on the floor. These elements have assumed different configurations in shows in Nigeria, Germany, Algiers, and Greece. Eke added a community component in Lagos by involving local residents in the labor-intensive process of fabricating the coats and umbrellas. He explains, ‘My idea is about the connection with people, the societies/cultures, and the environment, how one affects the other. So I will not feel fulfilled even when I can do the work all alone.’14 Community members paraded through the streets wearing the coats and holding the umbrellas, a public demonstration of the depreciated state of the source of life on Earth. Shields was a parade of grief, not celebration. It featured vulnerability, not power. It was designed to warn the onlookers, not entertain them.

For Eke, the linkage between packaged water, raincoats, and umbrellas signals crisis that my be even more dire than tainted waters. This defensive triad is a symbol of numerous dangers that now beset humans. Formerly care free, productive engagements with water, soil, sun, and wildlife are now ruled by fear. When they occur, they often involve protective clothing and other defensive barriers. Humans are the victims and the perpetrators of these calamities. Eke ponders the gravity of such issues by commenting, ‘We have continued to produce and consume a lot of toxic and dangerous chemicals that cause the deterioration of the Earth: water and air pollution, deforestation, acid rain, endangered species etc. simply because we do not care. I just wonder why it is in the nature of man to be ruthless, and I am afraid he does not seem to be scared of this impending ecologic crisis.’15

Eke seeks the source of this quandary by posing three questions on his blog, ‘Who am i? Who is the Other? Where is the meeting point?’16 His answers are implied by breaking two rules of written English. First he used the lower case to write the word ‘I’ which diminishes the significance of the individual. Then he capitalized the word ‘other’ which augments the importance of community, consisting of other humans, other species, and other forms of matter. ‘I’ has not always been capitalized in the English language. Significantly, ‘capitalization’ emerged at the same time as ‘capitalism’ — when Britain and the United States ascended into world powers in the 18th and 19th centuries. Like the capital ‘I’, the economic construction of capitalism endorses private ownership, private investments, private property, and private profits. While the comforts and conveniences generated by these systems are enjoyed by many, Eke directs attention to the stresses and hazards they also engender. He comments, ‘It is high time we changed our notion of ‘Modernist individual freedom’, which only meant freedom from community, freedom from obligation to the world, and freedom from relatedness.’17 He offers a poignant confirmation of the ethics of ‘eco centrism’, the belief that suppressing the dominant ‘self’ can avert many environmental calamities and social inequities.

Eke sums up his artistic enterprise by noting how water reestablishes bonds between individuals, cultural traditions, community, resources, and habitats: ‘Water is a universal medium. It’s common to everybody, no matter who or where you are. Whatever I do with water is what every other person does with it in every part of the world. The most interesting part is that we are bound or connected by [water.]’18

II. GERDA STEINER & JORG LENZLINGER: THE PERIL OF SCARCITY

Gerda Steiner born 1964 Ettiswil, Switzerland

Jörg Lenzlinger born 1967 Uster, Switzerland

A GOOGLE SEARCH OF ‘Gerda Steiner/ Jörg Lenzlinger’ is rewarded by a deluge of postings by bloggers who were dazzled by the visual wonderlands the artists construct, especially those that function like giant living systems that conduct nutritional cycles, via a network of tangled tubes and cables, among and around the visitors to their massive installations. These installations are created collaboratively by Gerda Steiner who is known for creating room-sized wall paintings, and Jorg Lenzlinger who uses crystallization as his artistic process.

This ambitious practice is channeled into a searing indictment of contemporary human interventions to the Upper Yarra Dam, which was constructed to remedy the seriously dwindling water supplies around Melbourne, Australia. The Water Hole (2008-2009) evokes the crisis of scarcity, the consequence of overgrazing, climate change, and the general the squandering of water resources to generate industrially induced abundance. It captures the distressing scene the artists observed when they visited Australia. They provide a vivid accounting of this experience: ‘The dammed water shoots down a thick pipe into the thirsty, booming city below, branching off into millions of smaller pipes until it is swallowed up in wash basins, showers and bathtubs – the urban water holes. Between the ferns and the dripping car wash sponge there lies a dried out landscape. The people of the city barricade themselves in little rooms, mostly alone, to celebrate the urban rituals of the water hole, after which the water is always dirtier than it was before. It is time to turn this situation around.’19

Evidence of the severity of this water shortage accumulates as visitors move from station to station within the meandering installation. The first sign that this journey will be ominous is the distinctive sound of rustling leaves. Trees are arrayed near the entrance, but their branches are bare. This essential component of living trees is replaced by silver foil, a synthetic material that leads visitors into a territory that is not functioning according to the biological patterns. The foil is supported by the trees’ branches to form the entrance tunnel. Visitors navigate this long passageway until they arrive at an opening that is filled with a chaotic heap of water-related items – bottles, buckets, funnels, toilets, wash basins, shower caps, drainage pipes, umbrellas, and bathtubs. Their overwhelming presence emphasizes the missing element. The entire collection is grievously dry. A disorderly clutter of contemporary bric-a-brac dangles from strings and lies scattered about. The artists’ description of a single detail conveys the abnormality of the situation, ‘Alongside the farting beans, hairy mobile phone spiders hatch from mutating eggs and play with the bones that are scattered around.’20

Liquid appears in only two locations within this parched landscape evoked by the installationo. A pool of waste motor oil, with its rainbow colored swirls, is disconcertingly beautiful, even as it signals the role of petroleum in diverting and fouling great quantities of water, which it does during manufacture, use, and disposal. Its distressing counterpart is a water hole. But instead of offering refreshing pure water, it is represented by a mud-splattered depression in an old worn mattress. This site resembles a miniaturized version of a muddied, half empty dam in a barren landscape. To augment the pitiful condition of this reservoir, a medical pouch hangs from above, presumably providing emergency treatment – one drip at a time. Steiner and Lenzlinger explain this component of their installation: ‘The network of pipes links all the urban water holes and is ready to channel the eagerly awaited rain into the clay pit which lies on the golden bed.’21

Visitors are then directed to a dark area where windows look out on to the tower of dry water implements and the water hole they have just passed through. Binoculars are provided, allowing people to ‘gain perspective’ on these recent experiences. A water dispenser in this area offers visitors a refreshing drink as they contemplate the probability of water deprivation. Steiner and Lenzlinger refer to this station as an ‘observation room’ because it provides ‘the opportunity to study your own species and your behavior in a reversed environment.’22

The next stations offer opportunities for visitors to lie on water beds and watch videos of rain and spurting water to add emotional resonance to evidence of its absence. This bleak, drought-ridden journey culminates at the end of a narrow corridor where a desk is installed. Glass tubes, vials, flasks, candles, and a microscope are laid out on it. A sign announces their intended use. This is a ‘Desalination plant for tears.’ All the equipment needed to conduct the desalinization process is provided. There is even a diagram illustrating how to use these items. It describes a ‘tear system’. The artists offer a wry conclusion, ‘And if the rain truly never comes again, we can still drink our tears.’ 23

III. YUN-FEI JI: FAILURES OF AN ENGINEERING TRIUMPH

Born 1963 Beijing, China

‘WHEN YOU SEE THAT THE people have been treated badly, you can be sure that nature is being treated even worse. When you defend one, you defend the other.’24 This declaration by Yun-Fei Ji was also expressed with brush strokes that chronicle the sorrowful plight of 1.5 million Chinese. This number represents entire populations of three cities, 140 towns, and 1,350 villages that have been expelled from their homes and their homelands to make room for the largest, and potentially the most destructive, hydroelectric dam in the world. The Three Gorges Dam was designed to boost China’s mad dash race to catch up with power-consuming industrialized nations. Yet recently, even Chinese officials have ceased boasting about this technological venture. The dam is inundating the habitats of countless species of mammals, amphibians, birds, and plants, along with myriad sites of archeological treasures and family legacies. In addition, concern grows about the people who have not been evicted, but whose homesteads surround the 370 mile-long dam. Despite importing 350 billion cubic feet of rock and earth to construct this massive structure, this population now lives in jeopardy of landslides, waterborne diseases, fish die-offs, and water contamination from the submergence of hundreds of factories, mines and waste dumps. Ji painted Migrants of the Three Gorges Dam, a ten-foot long narrative scroll, to document the hardship to these people and their lands.

Beyond feeling sympathy for the victims of the dam, Ji perceives the project as an affront to the beliefs that guided the Chinese people for thousands of years – that nature was the source of wisdom, the ‘Mother of All Things’. By balancing the yin and the yang, it assured eternal renewal. Ji decries the fact that this mediating balance sheet has been overtaken by abuses committed in the name of progress: ‘I want to develop a new set of metaphors, a new way of looking to reflect the condition on the ground today. We do not see nature as something nurturing as in tradition. Scholars used nature as a way to purify themselves. They learned cosmic law from meditating on nature. But today, our way to nature is cut off. We see nature as something to yield profit and exploit. It is a place to dump garbage we don’t want.’25

Ji’s indignation is bolstered by verifiable information and historic facts about the nation where he spent the first 26 years of his life. He states, ‘My job is to see the reality clearly. That is why I travel and research. That is part of my work.’26 This statement may seem unremarkable in countries that encourage independent research, but in China during the Cultural Revolution, it was a punishable offense. Even as a student, Ji questioned what he learned in school because it excluded the rich traditions of folktales, religious beliefs, and cultural achievements he learned about from his elders. ‘When I came to the States later, I became more aware that I was lied to in China. You can’t get true information by going to school in China because the history is rewritten. I wanted to find out what really happened. Through my art project, I’m trying to understand.’27

Ji’s research is less an academic pursuit than a journey of personal discovery. One of his first discoveries was that China’s rush to industrialize followed its defeat during the Opium Wars. Until then, China isolated itself, believing it was so superior there was nothing to gain by interacting with ‘barbarians’. Ji remarks, through this humiliating war ‘China gained the knowledge that you have to be modern so you are not beaten down. The goal was to catch up with England in fifteen years and US in twenty. Its traditional belief systems, Confucius and Taoism, had to be pushed aside to create this new China. The Maoist Revolution was radical. It meant smashing the old to meet these high goals. This includes building a major dam on the Yangtze River.’28

Ji came to realize that, in order to pursue progress and profit, the Chinese people were being robbed of traditions rooted in intimate interactions with the soils, waters, plants, and animals. To learn about these traditions, he visited surviving remnants of agriculture life styles in China’s ancestral lands. That is when he discovered disturbing evidence of forced relocations of masses of people into hastily constructed cities hundreds of miles away. The relentless churning of factories, not the seasons, suddenly determined the rhythms of these peoples’ lives. Migrants from the Three Gorges Dam documents these discoveries and their ethical and emotional fallouts. ‘Chemical companies dump their pollution into poorer areas. People can’t see the sun. The sky is a perpetual grey. They can’t even breathe the air. In the village where my grandmother lived, they built a mine up the mountain where rivers were fast and self- cleaning. Now rivers become static. Rich fertilizers from agriculture cause algae blooms. The new geological environment creates mudslides. Now the people can’t get water and the fish die.’29

These social and environmental concerns are embedded in Jo’s art medium, format, style, and technique. His artistic choices defy the broad policy of suppression during the Cultural Revolution that had not only crushed ancient cultural traditions; it landed fiercely upon modern art. Social Realism was the one permissible form of artistic expression when Ji was a student. Thus centuries of Buddhist art and decades of vanguard art were both missing from his education.

Ji began the project by traveling, creating drawings and then assembled them to construct scenes of stragglers, scavengers, and ghosts occupying lands slated for the flooding. These composite compositions formed the basis of the painting’s narrative which reads from right to left in the manner of traditional Chinese scrolls. Migrants from the Three Gorges Dam was also reproduced as an artist’s book by the renowned Rongbaozhai studio (‘Studio of Glorious Treasures’) that was once part of Beijing’s imperial enclave in the Forbidden City. The book version of the painting also takes the form of a scroll. The printed imagery was produced in the traditional manner with over 500 hand-carved, pear wood blocks.

The opening image presents trees, branches, and mountains. It would constitute a delightful landscape except for the inclusion of a tractor — an ominous sign of impending changes.

The final scene consists of five uniformed soldiers seated in rows on a raft patrolling a vast expanse of water, presumably the dammed Yangtze River. Their postures convey authority for maintaining order. The scenes in between portray masses of people situated among a clamorous disarray of carts, bicycles, and trucks heaped with bundles of belongings and furniture. They are dejected but calm, seemingly resigned to a fate they cannot resist. Two men wearing Western-style suits appear in one chilling scene. Their heads are covered with cloth hoods, the kind that is placed on criminals just before hanging or execution, suggesting that the actions of these Western investors are comparable to crimes that are capitol offenses. A monstrous rat also makes an appearance. According to Ji, its bloated belly, long snout, grizzly fur, and beady eyes resemble corrupt Chinese officials who prosper as citizens suffer. This grotesque figure towers over the people who appear to have grown accustomed to its presence in their lives.

Scene after scene evokes the current loss of land and its wildlife, of ways of life and connections to ancestors – all casualties of modernization. In order to resuscitate homeland traditions, Ji emulates the elegance of the Golden Age of Sung landscape painting 1,000 years ago. But instead of sublime transcendence, Ji’s version exposes the current government’s ruthless policies and actions.

Calligraphy is one way Ji revives a threatened tradition. It appears in the areas beyond the pictorial component of the Migrants scroll. However, instead of an inspirational poem as is the custom, Ji’s calligraphy enumerates China’s longstanding ambitions to tame the Yangtze River and the regrettable outcomes of these efforts.

The hand-painted scroll format connects Migrants to the five-thousand year history of Chinese art. Ji explains, ‘I learned scientifically correct anatomy and one/two/three point perspective. When I went to see old art in China, I discovered a different way that was not backed by scientific knowledge; it was backed by tradition. The artist was moving, not standing in a fixed place. That way is closer to experience. Things gradually unfold while we are walking, looking and seeing.’30 This compositional device perfectly suited a painted portrayal of the plight of an estimated 1.9 million people and hundreds of miles of land. Scenes merge, overlap, and stack.

Techniques used to render these scenes with brush and pigment provided another entry into China’s cultural legacy. Ji comments, ‘The process of applying ink with the flexible hair of the brush is an elaborate culture. Minute differences have ritual clarity.’ The particularities of each kind of stroke used to depict the migrants are as expressive as the subjects they convey, and as the words that denote them – withered, moist, gathering, dismissing, serious, free, young, old, quiet, busy, vigorous, charming, etc.31 ‘When you study traditional Chinese painting,’ Ji recalls, ‘you learn that even a simple horizontal line is made with the image of a layered horizontal cloud formation in mind. A dot should be like a suspended rock about to roll down the hill.’32 Ji uses the word ‘meditate’ to explain that the painting process goes beyond thinking and copying. He says, ‘It brings real life experience into painting. The energy is alive.’33

Ji’s material choices affirm that ancient cultures were more sustainable than their modern replacements. They are all indigenous to the Chinese mainland. Inks and pigments, for example, derive from local mineral and vegetables. The mulberry and rice papers were made in the traditional manner from local trees. They were mounted on silk woven from native silkworms. Native sheep, fox, goat, wolf, and horse provided the hair for his brushes. Ji summarizes the challenging cultural assignment he has chosen by stating. ‘To serve the country means bringing knowledge into human relationships. Poetry and art have to change. They have lost their sources of inspiration. We can still go to surviving pristine mountains, but we have to face the problems today. As artists, we need to find new metaphors to address these problems. My The Three Gorges scroll is a meditation on a ruin. That is our legacy.’34

IV. LINKS AND VIDEOS

Bright Ugochukwu Eke

Video of Bright Eke discussing his work in 2009

Video of Bright Eke installating a work in 2011

Gerda Steiner and Jorg Lenzlinger

Website of ‘Water Hole’ , 2008

Educational publication related to ‘Water Hole’, 2009

Video of Jorg Lenzlinger and Gerda Steiner presenting an overview of their projects, emphasizing ‘The Water Hole’

Nano Art: Controlling or Nurturing? Technology or Growth?

Yun-Fei Ji

Video of Yun-Fei J i ex plaini ng ‘Mi gr ants of the T hree Go r ges D am’, 2008

Video of Yun-Fei Ji describing his life and his career

Video of Yun-Fei J i ex plaini ng the d etails o f ‘Mi gr ants of the Thr ee Go r ges Dam’

END NOTES

2 David Hockney, ‘Autumn Pool (Paper Pool 29) http://megancerullo.blogspot.com/2010/12/artist-david-hockney-autumn-pool-paper.html

3 Versions of these essays appear in TO LIFE! Eco Art in Pursuit of a Sustainable Planet, University of California Press, 2012 by Linda Weintraub. http://www.ucpress.edu/book.php?isbn=9780520273627

4 Benedict Okereke, ‘Nigerians’ Forced Romance With Boreholes: Associated Hazards,’ http://www.nigeriavillagesquare.com/articles/benedict-okereke/nigerians-forced-romance-with-boreholes-and- their-waters-associated-hazards-starting-from.html

5 Bright Ugochukwu Eke, Artist’s statement, (October 29, 2008), http://u-bright.blogspot.com/search?updated-max=2008-12-08T08%3A43%3A00-08%3A00&max-results=7.

6 ‘Bright Ugochukwu Eke: Presentation,’ posted by ubrek2, (Nov, 15, 2009), http://www.youtube.com/user/ubrek2.

7 Matt Murphy: ‘Global Water Cycle & Supplies. http://academic.evergreen.edu/g/grossmaz/murphymw/

8 Bright Ugochukwu Eke, Telephone interview with the author, (March 30, 2010).

9 Jonas E Okeagu et al, ‘ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT OF PETROLEUM AND NATURAL GAS EXPLOITATION IN NIGERIA’, Journal of Third World Studies, (Spring 2006), 3, http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3821/is_200604/ai_n17179247/pg_3/.

10 Ibid

11 Andrew Walker ‘The water vendors of Nigeria,’ BBC News, (Abuja, Nigeria: February 5, 2009), http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/7867202.stm.

12 ‘Bright Ugochukwu Eke: Presentation,’ posted by ubrek2, (Nov, 15, 2009), http://www.youtube.com/user/ubrek2.

14 Bright Ugochukwu Eke, ‘BRIGHT UGOCHUKWU EKE: FLUID CONNECTIONS,’ by Celeyce Matthews, (delivered in a graduate seminar on modern African art at San Jose State University, May 13, 2009), http://u-bright.blogspot.com/2009/05/bright-ugochukwu-eke-fluid-connections.html.

15 Bright Ugochukwu Eke, Artist’s statement, (November 2,2007), http://u-bright.blogspot.com/search?updated- max=2008-09-29T08%3A55%3A00-07%3A00&max-results=7.

17 Ibid

18 Bright Ugochukwu Eke, ‘BRIGHT UGOCHUKWU EKE: FLUID CONNECTIONS,’ by Celeyce Matthews, (delivered in a graduate seminar on modern African art at San Jose State University, May 13, 2009), http://u-bright.blogspot.com/2009/05/bright-ugochukwu-eke-fluid-connections.html.

19 Gerda Steiner and Jorg Lenzlinger, The Water Hole, ACCA, Melbourne, (2008),

http://www.steinerlenzlinger.ch/eye_waterhole.html.

20 Ibid

21 Ibid

22 Ibid

23 Ibid

24 Yun-Fei Ji, Interview with the author, April 7, 2010.

25 Ibid

26 Ibid

27 Ibid

28 Ibid

29 Ibid

30 Ibid

31 ‘Chinese Painting’, Orientalgiftshop.com, http://www.orientalgiftsshop.com/seo/55/1/chinese_painting.htm.

32 Yun-fei Ji, ‘Artist Yun-fei Ji on how he paints,’ The Observer, (September 20, 2009). http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2009/sep/20/guide-painting-yun-fei-ji.

33 Ibid

34 Yun-fei Ji, Interview with the artist April 7, 2010.

SPECIAL BOOK DISCOUNT FOR WEAD MEMBERS

To Life! : Eco Art in Pursuit of a Sustainable Planet by Linda Weintraub

Go to ucpress.edu and save 25% with discount code 14W1529 at checkout. Discount expires July 31, 2014 and does not apply to e-books or books shipped to East or Southeast Asia.