In This Issue

-

Jourdan Imani Keith ● Your Body

-

Jackie Brookner ● Valuing Dirt + Water

-

Stacy Levy ● Working Earthworks

-

Daniela Corvillon ● Wastewater In Cuba

-

Linda Weintraub ● Tragedy of Wild Waters

-

Chris Drury ● Heart of Reeds

-

Betsy Damon ● 25 Years On Water

-

Basia Irland ● The Ecology Of Reverence

-

Suzon Fuks ● Waterwheel, Women & Collaboration

-

Susan Leibovitz Steinman ● DIRTY WATER

Working Earthworks: Revisiting the Spiral Jetty

I. REVISITING THE ICONS

ROBERT SMITHSON’S SPIRAL JETTY is one of the most frequently referenced works of environmental art. This huge spiral has been an icon in environmental art since it was created in 1970 on the Great Salt Lake in Utah. Spiral Jetty is the Mona Lisa of environmental art. This large earthwork berm helped spawn the ‘earthworks’ environmental art movement in the 1970’s that continues today. Smithson’s genius was to use a base material of no previous aesthetic value, the salty rock and earth of the dry lakebed, and manipulate it into a classic form of great beauty, at a scale commensurate with that enormous open landscape.

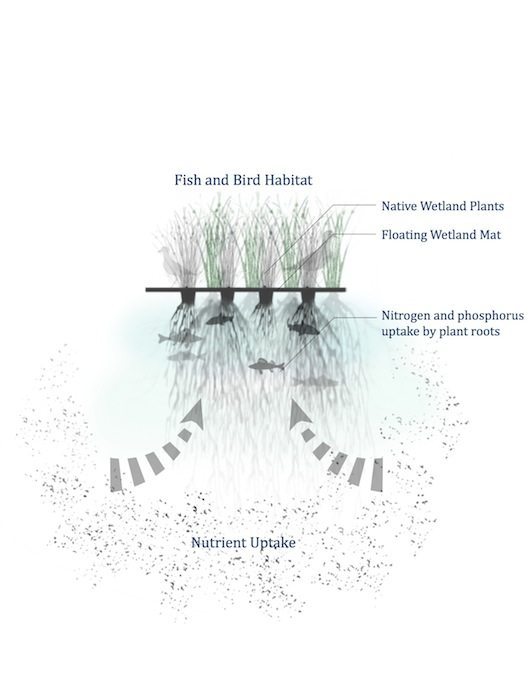

Spiral Wetland follows in the tradition of Smithson’s great piece, but it breaks new ground as living environmental art that participates in the processes of nature and heals the earth. This spiral is composed of floating mats of recyclable synthetic material and native wetland plants. Throughout the world, floating wetlands are used to extract excess polluting nutrients from urban lakes and ponds leaving cleaner water that benefits the entire ecosystem. Floating wetlands also create habitat for a wide range of ecologically important species from micro-organisms that process excess nutrients to game fish and frogs and amphibians who use the shade and hiding places the wetlands create. The opportunity to use these prosaic, malleable forms to create a sculptural object on the scale of the open surface of a lake, a sculptural object of beauty that also processes pollution and makes the lake a healthier living place, immediately intrigued me.

I have tried to express the hidden processes of nature to a broad audience through art. My goal has been to reveal the flowing patterns of water, the transportation of sediments, the growth of plants and the presence of micro-organisms – amongst other phenomena – to people in places where they live, work and travel. My work is also very committed to making places for people – creating art in communities, schools, rail stations, airports and neighborhoods. I often work with community engagement in the creative process. Art historical references did not consciously contribute to the generation of my ideas and projects until recently.

In fact The first time I incorporated historical references in my work was Straw Garden (2012) at the Seattle Center, Seattle, WA. Straw Garden was constructed of straw and coir (coconut fiber) wattles, materials which are typically employed to control sedimentation at construction sites or to repair eroded stream banks. The wattles, long, netting tubes stuffed with straw or coir, provide temporary, physical stabilization. Plants are usually inserted into or around the wattles to grow and permanently stabilize the site with their roots while over time the wattles decay and disappear. I was attracted to this material because of its interesting form and the temporary but critical role it plays in the process of healing damaged sites.

I was given a site of a large open lawn area beneath the Space Needle. Perhaps it was the lack of inherently meaningful space or the two overhead views available from the Space Needle and the monorail that got me thinking of the Baroque gardens of Andre Le Notre in Versailles where endless geometric ornamentation was the object of design. These formal gardens are typically seen from above. Reaching back to those parterre forms, Straw Garden took an immense Baroque pattern and recreated it with a modern material, planted with native plants. This temporary piece thrilled visitors to the Space Needle and travelers on the Monorail with its complicated scrolling pattern seen from above and gave the visitors on the ground a flourishing display of flowers and foliage for nine months. Upon deconstruction sections of the wattles, now filled with mature perennial plants, were adopted by the Seattle P-Patch Community Gardens and Seattle Public Utility Lands and live on today in gardens and landscapes across the city. There was not a plant that did not find a permanent home.

II. DEATH BY ABUNDANCE: THE EFFECTS OF NON-SOURCE POINT POLLUTION

LAKE FAYETTEVILLE IS A 194-acre lake situated on the edge of the city of Fayetteville in Northwest Arkansas. The town is fortunate to have its own lake where people can fish, boat and kayak. But the lake is suffering from the impact of non-point source pollution. Rain that falls on lawns and farm fields washes fertilizer and pesticides from those land surfaces into streams and ultimately into the lake. Non-point source pollution is diffuse and difficult to trace. It does not come from a single identifiable source like a waste pipe from a factory. It comes from all of the lawns and fields of the community. The most problematic pollutants contained in this runoff are the fertilizers nitrogen and phosphorus that are used to make lawns grow green and field crops produce abundantly. When nitrogen and phosphorus reach the warm waters of Lake Fayetteville they stimulate the rapid growth of enormous masses of algae. Instead of greening up lawns, these lawn and agricultural chemicals ‘green up’ the lakes and ponds with an overabundance of algae that then dies. As this dead algae decomposes, it uses up the available oxygen in the water. This process is called eutrophication. Eutrophication starves other organisms of oxygen and ultimately contributes to the biological death of the lake.

The best way to address this problem is to reduce or eliminate the sources of nitrogen and phosphorus that are washed off the land into the lake. But because those sources are so diverse and diffuse – lawns, gardens, agricultural fields, and faulty septic systems – this can be very difficult to achieve. Another way to reduce the over-abundance of nutrients is to absorb the nitrogen and phosphorus into alternative food chains, so that species other than algae can utilize the nutrients for growth. Wetland plants like rushes, reeds, sedges and cattails use the nitrogen and phosphorus to grow their roots, stems and flowers. On their roots they also nurture large colonies of periphyton, a living mix of microscopic cyanobacteria bacteria and hetereotrophic microbes that absorb enormous quantities of nutrients. The more nitrogen and phosphorus metabolized by wetland plants and their periphyton, the less is available to feed the algae masses.

III. BIOMIMICRY AND THE BENEFITS OF FLOATING WETLANDS

WETLANDS ARE EXCELLENT AT processing nutrients. But many disturbed waterways no longer have any functioning wetlands along their shores. Sometimes the shore has been urbanized or invasive species have driven out the diverse native communities of plants that are so effective at nutrient uptake. Another problem are water levels that fluctuate wildly due to increased rain-water runoff from impermeable urban surfaces like streets, parking lots and building roofs. Water level fluctuations can alternately drown wetland plants during storms and strand them without water in drier periods. Floating treatment wetlands (FTW) are one way to replace the missing natural wetlands. These floating mats of wetland plants mimic nature, and provide concentrated areas of wetlands to absorb nutrients and provided missing habitat for fish and amphibians — just what a water body needs. Floating wetlands are frequently used to extract nutrients from polluted lakes, ponds and slow moving rivers in Europe, Southeast Asia and China. They ‘biomimic’ the ecology of natural wetlands. They are indeed wetlands, but inhabit the surface of the water rather than the edge/shore line, and are not deleteriously affected by changing water levels, so they do not dry out in droughts nor get inundated in high water the way shoreline wetlands do. This kind of considered artifice seems a natural fit for sculpture.

The sculptural potential of floating wetlands first occurred to me when I was collaborating with Biohabitats Inc., a restoration ecology and design firm based in Baltimore, MD. We were working on the Washington Avenue Green project on the Delaware River in Philadelphia, PA. Biohabitats Inc. was testing floating wetlands in the river as a possible application for tidal situations. Unlike constructed wetlands on shore, floating wetlands are not eroded by the river. They simply float on the surface and move with the flow of water. Though wetlands installed on the edge of water bodies eventually become resistant to erosion, they are very fragile until the plant roots develop and interlock with the soil. But floating wetlands—a composite material or coir mattress with inserted plants—are resilient from the moment they are installed. When I saw Biohabitat’s square, floating wetland mats riding the surface of the Delaware River, I recognized the sculptural possibilities of this living material. Interesting and intricate forms could be employed to both function and have a compelling presence on the water. As I watched the wetlands grow over time, I thought how Smithson’s Spiral could be revisited with a new, living material.

IV. FLOATING THE SPIRAL

THE PERFECT PLACE TO CREATE the new wetland spiral arose when The Walton Art Center of Fayetteville, AK commissioned an artwork for Artosphere — an annual festival focused on arts, nature and sustainability for Northwestern Arkansas in 2012. The idea fit the mission of sustainability and art. Getting the project underway required extensive community consultation with natural resource organizations such as the Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission, Arkansas Fish and Game Commission, Beaver Water District, Beaver Watershed Alliance, Lake Fayetteville Watershed Partnership and the Lake Fayetteville Parks and Recreation Board. Fishing and boating concessionaires on the lake were very enthusiastic about the improved fish habitat that Spiral Wetland created. It was an important understanding by these organizations that art could do some ecological work. After many meetings and memos, this large scale art installation on the lake became a reality.

Volunteer kayakers, cave divers, surveyors and Walton Art Center staff all helped to assemble and install the project. The pattern was first laid out by surveyors on a grassy patch near the shore of the lake. The foam mat was cut to the giant pattern and stitched together with plastic hardware. The same spiral shape was then laid out on the surface of the lake using surveying equipment and anchors marked with buoys. The spiral mat form built on the lawn was then taken to the shoreline in smaller sections. While floating in shallow water, the mats were planted with 7,000 plugs of Soft Rush Juncus effusus, a native plant that inhabits the edges of lakes and ponds.

The planted sections each got towed out by kayak and attached to the 23 anchors in the lake. After a basic layout was anchored, Cave divers worked in the murky water to adjust the anchors so that the spiral shape would hold. Then strips of spikey bird wire, to prevent geese from getting on the spiral from the water and eating the young plants, was carefully sewn onto the perimeters of the spiral. Shore birds could land on the narrow mats but the ‘landing strip’ was too narrow for flying geese. The installation process, from land layout to final anchoring and attaching of anti-goose wire, took place over a three-week period and the spiral was completed in early May 2013.

Even in a small way, the spiral had immediate impact on the lake environment. Within days, common sandpipers and the rare to this region Dunlin (Calidris alpina) appeared on the mats while turtles swam nearby, attracted to the plant roots. The fishing community appreciates the addition of shaded habitat for fish. Though this size of floating treatment wetlands is too small to have a major impact on the overall chemistry of the water, it does create an example of how the lake water could be treated using plants to do the work of taking up excess nutrients. The piece works as a suggestion of the possibilities for a new kind of visually exciting, aesthetic engineering to improve the environment.

The Spiral Wetland is not permitted as a permanent installation. The piece can be moved around the lake or removed entirely with no disturbance to the local conditions. This flexibility and impermanence made the floating wetland much more acceptable to the stakeholders. But growing temporary installations can be similar to a Flower Show—a sort of plant- based spectacle that can be very wasteful of the living materials. I wanted the project to be sustainable, not disposable. So, as in Straw Garden ‘adoption’ became the essential step to complete the project. When the time comes to remove Spiral Wetland from Lake Fayetteville, the floating wetland will be divided into segments that will be transported to other water bodies, like retention basins and backyard ponds. The plants can survive a quick trip to a new site, where they will continue to live out their days providing beauty and ecological functions in new venues. Disseminating the artwork is like spreading the creative seeds to the community and the local environment.

V. FROM SPIRAL JETTY TO SPIRAL WETLAND: THE MORPHING OF EARTHWORKS

SMITHSON’S SPIRAL JETTY WAS a powerful tour de force for its generation: one man’s gigantic vision, a berm of basaltic stone deposited on the yielding floor of the Great Salt Lake. And so as a monument it endures.

In a way Spiral Wetland takes the next step.

Spiral Wetland floats on the surface of Lake Fayetteville, anchored but flexible, laced with living plants breathing life into the water. Not permanent but transformative, a knitted part of nature, not something extracted from the Earth by machines. Spiral Wetland will live on not as a monument, but as a thousand leaves of grass.