In This Issue

-

Jourdan Imani Keith ● Your Body

-

Jackie Brookner ● Valuing Dirt + Water

-

Stacy Levy ● Working Earthworks

-

Daniela Corvillon ● Wastewater In Cuba

-

Linda Weintraub ● Tragedy of Wild Waters

-

Chris Drury ● Heart of Reeds

-

Betsy Damon ● 25 Years On Water

-

Basia Irland ● The Ecology Of Reverence

-

Suzon Fuks ● Waterwheel, Women & Collaboration

-

Susan Leibovitz Steinman ● DIRTY WATER

Art as Indictments of Global Water Abuses

INTRODUCTION

WATER HAS A SPLIT personality. On the one hand, it is gregarious, continually absorbing and dissolving other materials. Water’s remarkable versatility is epitomized by its capacity to dissolve both acids and bases. On the other hand, it is meddlesome, actively seeping into the tiniest crevices of the Earth and permeating the greatest expanses of the atmosphere. Its all-powerful influence on Earth’s conditions is exemplified by its ability to transport any particle or chemical it encounters throughout the globe. Thus, on the one hand, water serves as an agent for cleansing, purifying, protecting, synthesizing, nourishing, combusting, and delighting. It is the unique liquid that enables life and is essential for health and vitality. However, water also transmits death, disease, and deformity. Thus, water shortages are not the only cause of stress on humans, plants, animals, insects, and bacteria. They are at risk even in regions of the globe with access to water. According to a UNESCO report, “Water-related diseases are among the most common causes of illness and death, affecting mainly the poor in developing countries. They kill more than 5 million people every year, more than ten times the number killed in wars. These diseases can be divided into four categories: water-borne, water-based, water-related, and water-scarce diseases.”

The massive scale of squandering and abuse by humans has stripped water of its powers to heal and nourish. Once honored as the sacred source of creation among the ancient Babylonians, Pima Indians, Hebrews, Greeks, Aztecs, Egyptians, East Indians, Chinese, etc., the waters that course through contemporary lives has either been demoted to a formless, colorless, tasteless, and odorless liquid that flows predictably from a tap, or it looms into consciousness as a fearsome toxic menace. An arsenal of purifying treatments has been developed to decontaminate this former symbol of purity. They include filters, ultraviolet zappers, ionization, chlorination, etc.

Joseph Beuys addressed humanity’s skewed relationship with the Earth’s waters in a 1971 when he performed “Bog Action.” The performance survives as a photograph depicting Beuys, fully clothed in his signature thick-soled shoes, dark slacks, white shirt, and felt hat, leaping joyfully into a murky brown bog. It requires no stretch of the imagination to realize why the word ‘bog’ is slang for ‘toilet’ in Britain. The squeamish ‘Yuk!” response is evoked because the thick, brown, boggy waters, that consist of decaying plant and animal matter, resembles the contents of a toilet. Beuys’s blissful leap reveals a contrasting attitude. To Beuys, the wetland was misjudged, maligned because it did not conform to aesthetic measures of beauty. But it functioned beautifully by maintaining the ecological health of the watershed. His immersion honored the valuable role that bog waters play in producing oxygen, sinking carbon, cleansing water, producing organic molecules, and supporting diverse plant and animal organisms.

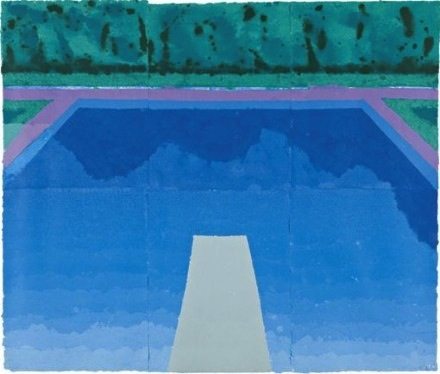

The public’s squeamishness regarding natural bodies of water factor into David Hockney’s popularity. Hockney earned renown in the 1970s by creating paintings depicting sylvan swimming pools, not ponds, lakes, or bogs. The water in these paintings is crystal-clear and cobalt-blue. It not only accounts for each painting’s visual appeal, it reinforces viewers’ preferences for water that is a product of engineering, not nature. Pool water is pumped through filters, treated with chemicals, and otherwise sterilized to remove the forms of organic matter that Beuys relished in the bog. It seems that the water that is desired today is ‘treated’ and ‘domesticated’, not ‘natural’ and ‘wild’. The waters in Hockney’s renowned paintings are stripped of their sacred power to foster health and growth. These works of art epitomize an era in which natural bodies of water are suspected of containing unsavory concoctions of effluents from sewage and industrial processes, and teeming with unidentified populations of micro organisms.

Each of the works of art discussed in the accompanying essays reveals a particular contemporary water calamity. Tainted water that falls as acid rain in Nigeria is the topic of Bright Ugochukwu Eke’s community project. A severe water shortage in Australia inspired Gerda Steiner and Jorg Lenzlinger’s mournful installation. The engineered social and environmental atrocity known as the Great Gorges Dam in China is lamented in a narrative scroll by Yun-Fei Ji. Together, they explore the theme of water in terms of lack, excess, and mismanagement, all reasons why distress now accompanies such elemental functions as drinking and bathing for many people across the globe.3

Before embarking on these disturbing narratives of abuse, let us pause to take note of water’s remarkable attributes as a precious resource:

– Water distributes the substances that it dissolves or suspends.

– Water erodes, etches, and carves hard substances.

– Â Water conducts heat.

– Â Water cleans by dissolving loosely bonded compounds.

– Â Water softens many materials.

– Â Water evaporates, condenses, freezes.

– Â Water creates clouds, fog, rain, snow, mist, dew, sleet, hail, flood, etc.

– Â Water flows downward due to gravity and it creeps upward due to capillary action.

– Â Water is the habitat that supports the greatest concentrations of species.

-Â Â Water cleanses and uplifts the spirit.

-Â Â Water is essential for life.

-Â Â Water can kill.

I. Â BRIGHT UGOCHUKWU EKE – ACID RAIN CHECK

Born 1976, Nsukka. Nigeria

THE NIGERIAN ARTIST Bright Ugochukwu Eke laments the wholesale corruption of much of the planet’s waters which are endangering life and sabotaging water’s time-honored role as an embodiment of life, birth, and renewal. He asks, “How do we understand ourselves? I thought of a common language in nature. Water is a precious natural medium/resource with a universal language. It occupies the largest part of the earth, but has been disrespected, polluted, and contaminated with the advent of industrialization. It has been forced to lose its spirituality and purity.”5

Eke sought a way to translate his lament into the language of art. He explains his dilemma,

“All the actions of water pose problems to man and society. How can my expressive engagement deal with these problems? So in trying to come to terms with some of these questions, I have to think of what man has done to water, what water has done to man. That led me to question the relationship between man and the environment. I see water as a water medium with a water language. I thought it would be necessary to use water as a metaphor to articulate my ideas about man’s relationships. I’m using a small part to talk about a whole phenomenon, of which one is acid rain.”6

Rainwater becomes noxious when water molecules dissolve acid particulates in the air. The particles originate from effluents emitted from factories, waste treatment plants, automobiles, fertilizers, and pesticides. They fall back to earth as acid rain. These events instigate a litany of environmental woes that include deforestation, reduced soil fertility respiratory and skin diseases, and ecosystems that can no longer support biological diversity. Most alarmingly, acid rain poisons drinking water. Just at a time when population growth is increasing the demand for potable water (which normally amounts to only 1% of the Earth’s total water store), acid rain is causing supplies of this essential liquid to shrink.7

Eke narrowed the aperture of his perception and attended to a single location (his homeland, Nigeria), a single water hazard (acid rain), a single jeopardy (contaminated drinking water), a single culprit (petroleum refineries), and a single indicator of the problem (packaged potable water).

A personal experience in Port Harcourt, a major industrial center in Nigeria, provides evidence of this regrettable state of affairs. He explains, “I was working outside in the rain. In two days I discovered skin irritation from toxic chemicals that go into the atmosphere from the industry. The emissions from the industry come down when it rains. I was not surprised as Port Harcourt has a lot of industries, especially in manufacturing and oil production. Then I came to think about not just myself, but the people who live in the area. What about the aquatic life? What about the vegetation?”8

Eke had this experience in the delta of the Niger River in Nigeria, which is blessed with abundant fresh waters that support one of the highest concentrations of  biodiversity on the planet. Yet these waters are now among the most contaminated, due in large measure to the fact that the region is also rich in oil. Since 1958, the petroleum industry has accounted for more than 90 percent of the nation’s total export.9 In Nigeria, productivity and contamination are linked because the country does not have a pollution control policy. There is nothing to prevent oil companies from spilling oil (which pollutes groundwater), and burning natural gas flares (which contaminates the atmosphere). Acid rain is so severe that the shelf life of the corrugated iron sheets used for roofing in most Nigerian villages has decreased from twenty years to five.10

Runoffs from petroleum processing and petrochemical plants dump tons of toxic wastes into nearby waters. This problem is compounded because few regions in Nigeria have ‘pipe-borne water’ that is treated. As a result, even the very poor who live in this rain-rich country must purchase drinking water. Throughout Nigeria, thousands of water vendors push heavy water carts around the rutted streets to sell water. It costs consumers approximately $480/year, a sum that is far greater than the cost of water in advanced countries.11 But even these waters may not be safe. Some water vendors sell surface water from scummy rivulets that may contain sewage. Others get their water by drilling boreholes that, in areas of mining and oil drilling activities, is often contaminated.

In Nigeria, both surface water and borehole water is packaged in cheap plastic bags called ‘sachets’. A disconcerting paradox emerges from this container because it is the petroleum industry’s negligence that makes the manufacture and purchase of these bags a necessity for survival. These bags are made of petroleum-based plastic! Ironically, drinking packaged water intensifies the demand for petroleum, which increases petroleum production exacerbating acid rain and groundwater contamination. As a result, the industry profits from the worsening the conditions that require water to be packaged.

Eke identifies yet another aspect of this troubling scenario by commenting, “The problem is that people buy the water in plastic bags and after use they throw them away and they become litter in the environment. You find plastic bags all over the place.”12 Besides being unsightly, discarded plastic bags pose a serious and enduring hazard to wildlife. Most plastic bags take centuries to decompose. They break down into toxic particles that mix with soil and endanger the food chain.

The proliferation of discarded sachet bags provided Eke with a compelling medium for conveying Nigeria’s water crisis through art. He and assistants gathered thousands of sachet water bags from the littered streets to create Shields (2005/06). The bags appear in this an installation in their soiled states so viewers can discern their source as discarded waste, which is familiar to them. At the same time, he contrived a way to present the sachet bags to convey the environmental perils they pose and the culprits responsible for this water plight. Â Eke explains how he accomplished these twin goals. “Now we need something that stops the same water from going in. So I picked up some plastic water bags and made out of these raincoats and umbrellas.”13Â The work’s title, Shields, dramatizes the need to protect the body against the dangers of rain that is laden with hazardous acids instead of healthful nutrients.

The rain gear was fabricated by tearing the sachet bags open and laying them flat so they could be ironed together along the edges. The resulting sheets of plastic were then cut and assembled into raincoats and umbrellas. The coats are long, hooded, unfitted, and unembellished. Stripped-down in this manner, they announce to viewers that the reason for their existence is exclusively functional. They reference emergency survival gear, not fashion or commerce.

The scale of the installation was determined by the scale of the water crisis it conveyed – both are large! 120 coats and 60 umbrellas filled the exhibition space to its limit, indicating that the enormity of the toxic effects of acidified rainwater. When the work premiered in Senegal, the raincoats were suspended from the ceiling and hung on the walls of the gallery. The umbrellas were scattered on the floor. These elements have assumed different configurations in shows in Nigeria, Germany, Algiers, and Greece. Eke added a community component in Lagos by involving local residents in the labor-intensive process of fabricating the coats and umbrellas. He explains, “My idea is about the connection with people, the societies/cultures, and the environment, how one affects the other. So I will not feel fulfilled even when I can do the work all alone.”14 Community members paraded through the streets wearing the coats and holding the umbrellas, a public demonstration of the depreciated state of the source of life on Earth. Shields was a parade of grief, not celebration. It featured vulnerability, not power. It was designed to warn the onlookers, not entertain them.

For Eke, the linkage between packaged water, raincoats, and umbrellas signals crisis that my be even more dire than tainted waters. This defensive triad is a symbol of numerous dangers that now beset humans. Formerly care free, productive engagements with water, soil, sun, and wildlife are now ruled by fear. When they occur, they often involve protective clothing and other defensive barriers. Humans are the victims and the perpetrators of these calamities. Eke ponders the gravity of such issues by commenting, “We have continued to produce and consume a lot of toxic and dangerous chemicals that cause the deterioration of the Earth: water and air pollution, deforestation, acid rain, endangered species etc. simply because we do not care. I just wonder why it is in the nature of man to be ruthless, and I am afraid he does not seem to be scared of this impending ecologic crisis.”15

Eke seeks the source of this quandary by posing three questions on his blog, “Who am i? Who is the Other? Where is the meeting point?”16 His answers are implied by breaking two rules of written English. First he used the lower case to write the word ‘I’ which diminishes the significance of the individual. Then he capitalized the word ‘other’ which augments the importance of community, consisting of other humans, other species, and other forms of matter. ‘I’ has not always been capitalized in the English language. Significantly, ‘capitalization’ emerged at the same time as ‘capitalism’ — when Britain and the United States ascended into world powers in the 18th and 19th centuries. Like the capital ‘I’, the economic construction of capitalism endorses private ownership, private investments, private property, and private profits. While the comforts and conveniences generated by these systems are enjoyed by many, Eke directs attention to the stresses and hazards they also engender. He comments, “It is high time we changed our notion of ‘Modernist individual freedom’, which only meant freedom from community, freedom from obligation to the world, and freedom from relatedness.”17 He offers a poignant confirmation of the ethics of ‘eco centrism’, the belief that suppressing the dominant ‘self’ can avert many environmental calamities and social inequities.

Eke sums up his artistic enterprise by noting how water reestablishes bonds between individuals, cultural traditions, community, resources, and habitats: “Water is a universal medium. It’s common to everybody, no matter who or where you are.  Whatever I do with water is what every other person does with it in every part of the world. The most interesting part is that we are bound or connected by [water.]”18

II. Â GERDA STEINER & JORG LENZLINGER: Â THE PERIL OF SCARCITY

Gerda Steiner born 1964 Ettiswil, Switzerland

Jörg Lenzlinger born 1967 Uster, Switzerland

A GOOGLE SEARCH OF ‘Gerda Steiner/ Jörg Lenzlinger’ is rewarded by a deluge of postings by bloggers who were dazzled by the visual wonderlands the artists construct, especially those that function like giant living systems that conduct nutritional cycles, via a network of tangled tubes and cables, among and around the visitors to their massive installations. These installations are created collaboratively by Gerda Steiner who is known for creating room-sized wall paintings, and Jorg Lenzlinger who uses crystallization as his artistic process.

This ambitious practice is channeled into a searing indictment of contemporary human interventions to the Upper Yarra Dam, which was constructed to remedy the seriously dwindling water supplies around Melbourne, Australia. The Water Hole (2008-2009) evokes the crisis of scarcity, the consequence of overgrazing, climate change, and the general the squandering of water resources to generate industrially induced abundance. It captures the distressing scene the artists observed when they visited Australia. They provide a vivid accounting of this experience: “The dammed water shoots down a thick pipe into the thirsty, booming city below, branching off into millions of smaller pipes until it is swallowed up in wash basins, showers and bathtubs – the urban water holes. Between the ferns and the dripping car wash sponge there lies a dried out landscape. The people of the city barricade themselves in little rooms, mostly alone, to celebrate the urban rituals of the water hole, after which the water is always dirtier than it was before. It is time to turn this situation around.”19

Evidence of the severity of this water shortage accumulates as visitors move from station to station within the meandering installation. The first sign that this journey will be ominous is the distinctive sound of rustling leaves. Trees are arrayed near the entrance, but their branches are bare. This essential component of living trees is replaced by silver foil, a synthetic material th