Location: Scotland

INTRODUCTION

Helen Mayer Harrison (1929-2018) and Newton Harrison (1932-2022)

HELEN MAYER HARRISON AND NEWTON HARRISON are pioneers in the creative development of art and ecology. It was Helen who read Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, a critical influence in their decision in the early 1970s to do no work that did not in some way benefit the ecosystem. This commitment became a compass throughout their lives as artists, shaping a practice unique in its focus and complexity. Helen was an English Major with a Masters in Psychology who had worked in education extensively and to a senior level before becoming a full-time artist and Professor at the University of California San Diego. Living in New York in the early 1960s she had also been the first New York Coordinator of the Women’s Strike for Peace. Newton, in contrast, had been apprenticed to the sculptor Michael Lanz from a very young age, and trained in figuration. He graduated from Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1952 and thereafter pursued a career as a sculptor. He took his MFA at Yale (1963-65) alongside Chuck Close and Richard Serra, and, Helen helped him learn Joseph Albers’ color theory. He went on to be one of the founding members of the new Department of Visual Arts at the University of California, San Diego CA where they both later became Professors Emeriti.

I. GREENHOUSE BRITAIN: LOSING GROUND, GAINING WISDOM (2006-2009)

Greenhouse Britain, Helen Mayer and Newton Harrison Greenhouse Britain 2006-2009

AS AUTHORS WE COME from the perspective of practice-led researchers. Over 30 years our research has been concerned with artists and their action in public life. Our research encompasses both attention to exemplary practices such as that of the Harrisons, as well as experimental work through live projects. We had the privilege of being able to do both from time to time. We first met Helen and Newton in 2005 at the Darwin Symposium, Shrewsbury, thanks to David Haley, a UK based artist and ecologist. We had the privilege to spend the next three years working with them to realize Greenhouse Britain: Losing Ground, Gaining Wisdom (2006-9), a project which prefigured their more recent work through the Center for the Study of the Force Majeure. It was through Greenhouse Britain that they first talked about the ‘form determinant’ which later became the ‘force majeure’.

We suggest that the existing plans for greenhouse emissions control will be insufficient to keep temperature rise at 2° or less. In this context, the rising ocean becomes a form determinant. By ‘form determinant’ we mean the ocean will determine much of the new form that culture, industry and many other elements of civilization may need to take. (Harrison and Harrison 2007, p.12)

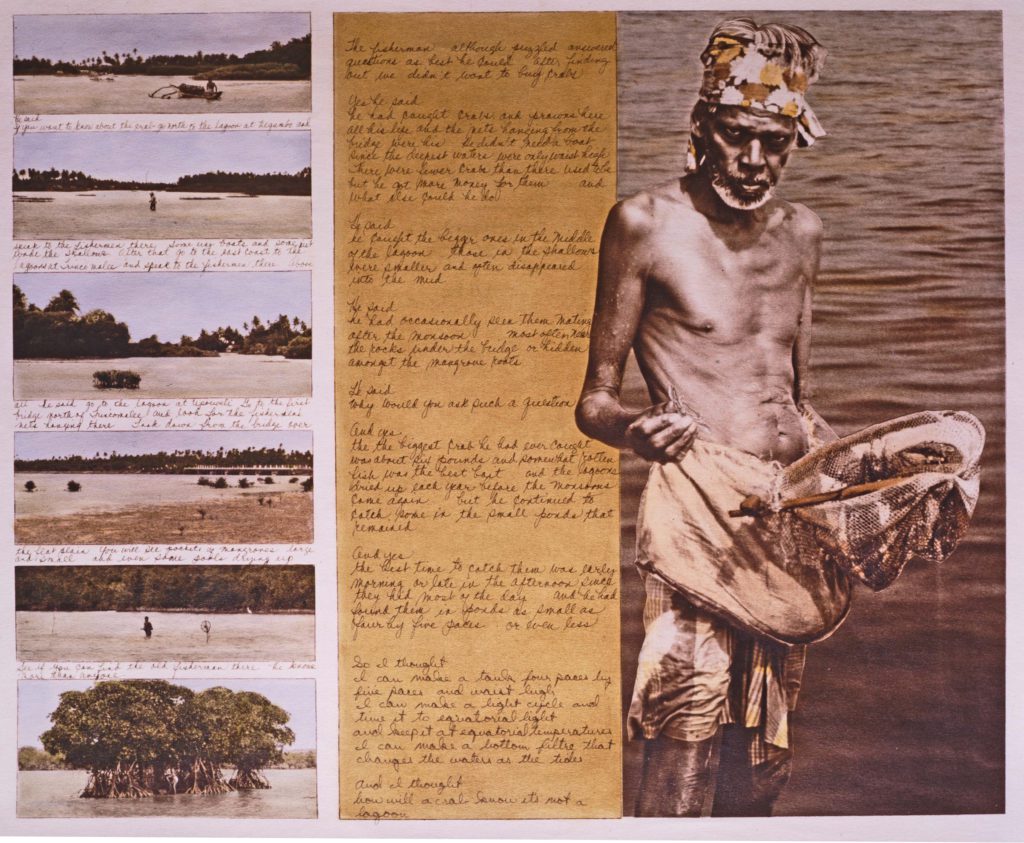

II. THE LAGOON CYCLE

The Lagoon Cycle, Helen Mayer and Newton Harrison, 1985.

THROUGHOUT THIS PERIOD we heard Helen read from the end of their magnum opus, The Lagoon Cycle, many times, in meetings, events and performances.

And the waters will rise slowly

at the boundary

at the edge

redrawing that boundary

continually

moment by moment

all over

altogether

all at once

It is a graceful drawing and redrawing

this response to the millennia of the making of fire

And in this new beginning

this continuously rebeginning

will you feed me when my lands can no longer produce

and will I house you when your lands are covered with water

so that together

we can withdraw

as the waters rise?

(Harrison and Harrison 2006, np)

Sometimes Helen started slightly earlier in the text, with the list of rivers around the world, but she always read this last section and it always drew a deep silence. The drawing and redrawing of a boundary aptly evokes the sustained rhythm of ocean and land at the littoral. The poem gently discounts the option to do nothing in response to an encroaching sea. As they discuss in the Seventh Lagoon in The Lagoon Cycle (Harrison and Harrison 1985, p.93), it is easy to fall into a monologue of ‘continuous approval’ and ‘continuing applause’, but this depletes energy. Dialogue conversely is ‘self-nourishing, self-cleansing, self-adjusting’, but dialogue is also difficult when there are no points of similarity. The Harrisons offer the following proposal: ‘Entertain empathy/and build patterns of similarity/thereby’ (authors’ emphasis). Conflicting interests are at the heart of the question being asked by sea level rise. In this article we will explore the role of empathy in the Harrisons’ work as evoked in this passage and indeed practiced throughout their career: that is the self-conscious effort of arriving at shared understanding across difference and through conversation.

III. CONVERSATION AS STRATEGY

CONVERSATION IS A KEYSTONE of the work of the Harrisons, conversation between each other as artists, with many scientists, and with inhabitants of the places in which they have made work. Helen highlights the distinctive perspectives and experiences that have enriched their joint practice and that continue to animate and deepen their commitment to the web of life.

One of us-who had been an artist from early adolescence on-had to change completely to do this. The other of us-who had been a lifelong teacher, researcher, educational philosopher, and student of psychology and literature- had to change completely to do this. We were convinced that neither of us had the capability to become eco-systemically empowered without the help, encouragement, and dramatically different talents, experience, and tolerance of ambiguity of the other. We began to imagine that there was a third party, a unique co-creator, and that we were assistants to this entity-the real artist only visible to us.

We were teaching each other to be each other, but not completely each other. (Harrison and Harrison 2016, p.51)

What does this approach, and its centering of a space of exchange across difference, tell us about empathy?

Helen’s description of their separate histories and processes of adaptation resonates with the way that Edith Stein defines empathy (Stein 1989). For Stein, a philosopher and phenomenologist working in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century, empathy is a process. Often reduced to mean ‘a feeling of oneness’, empathy is in Stein’s understanding, an experience in which we are faced with the unfamiliar or foreign. In making the effort to reach out to the ‘not I’, we reflect and learn to assess ourselves, to become clear who we are and what we are not. We uncover and develop those other selves that may be asleep in us. Although a feeling of oneness may be made possible through empathy, it is not a given and indeed may not even be desirable. As Helen comments above, ‘We were teaching each other to be each other, but not completely each other‘ (authors’ emphasis).

Newton recently commented that the web of life itself is beyond the human imagination, unattainable, but this does not diminish the importance of attempting the task (Harrison 2022). The Harrisons’ willingness and effort to be open to the unfathomable characterizes their work. This matters to the discourse in ecology in emphasizing the importance of moving beyond what we are comfortable with knowing and seeing.

Although the Harrisons are often referred to as this unified entity, their work, in particular The Lagoon Cycle, is built around two voices, the Lagoon Maker and the Witness. These characters are a very powerful evocation of the potential for two people to combine action and reflection. The Lagoon Cycle opens with a backwards and forwards sequence of ‘I said’ and ‘you said’ statements about what it means to tell the story of making something, anything. Two key ideas become clear – one that in making something you start in the middle and need to figure out where you began and where you are going. The second is that every telling of the story is different. The introductory text then moves on to a meditation on the transition from two people in their own worlds to some form of mutual recognition

An experiment……a bargain

A transaction of sorts

To discover if we are

each other’s invention

(Harrison and Harrison 1985 p. 26)

IV. UC SAN DIEGO

IN SAN DIEGO THE HARRISONS were close friends with David and Eleanor Antin and connected with Jerome Rothenberg and the ethno-poetic movement. Ethno-poetics is concerned with the power and beauty of the spoken word. It is concerned with breaking out of the dominance in the Western tradition of the written word, but not just the written word. It challenges Western ways of thinking and acting through ways of living that are closer to the natural environment and therefore crucial to ecological thinking. Rothenberg pointed out

The suspicion came to be that certain forms of poetry, like certain forms of artmaking, permeated traditional societies ∓ that these largely religious forms not only resembled but had long since achieved what the new experimental poets & artists were then first setting out to do. (Rothenberg 1994)

Helen, bringing a certain quality of literature and performance into their practice, opened up the possibility that the ‘social- spiritual as well aesthetic’ (as Rothenberg puts it) can become intertwined. Newton brought scale and the power of the visual and material to create space and time. Through his deep understanding of the sculptural, the works locate us physically and haptically in ways in which the ‘here’ of a particular place and ‘now’ of a moment in time focus on our experience of place and the combination connects us to the dynamics of the Earth’s ecosystems (Fremantle and Douglas 2020, pp.92-4).

During the early 1970s, when Helen and Newton were negotiating the working relationship that would become ‘the Harrisons,’ Helen was active in the feminist art scene on the West Coast. Her involvement was documented by the esteemed feminist writer/critic Arlene Raven in the At Home catalog (Raven 1983). This exhibition traced feminist art in the US from 1970 through to the early 1980s. The Lagoon Cycle, amongst other works and events involving Helen, is included in this chronology. Raven defines the work of feminist art of the time in ways that correspond to our exploration of empathy. Feminism, as developed by Raven, extends empathy from a purely interpersonal experience into one that is concerned with building a world in common.

Feminist artists, especially, search for forms which can reach from one’s own experience to embrace the varied circumstances of other people’s lives. Conversely, new forms continually emerge from the gathering of people to share with one another and to work together. (Raven 1983 p. 29 italics in the original)

The essay goes on to highlight how the Harrisons gather a support system to create works which enact the ‘ return of natural resources or urban viability to these same groups ‘ This ‘ makes the people who experience their art the constituency sponsoring a project, the participants in the project, the audience, and the custodians ‘ (Raven 1983 p. 33). A new and more complex relationship between artist and audience is made possible involving the audience in becoming ‘custodians’.

Workplace, Helen Mayer and Newton Harrison, 1983.

Helen and Newton’s contribution to At Home is Work Place, an installation representing the front room of their own house. They inhabited the installation, beginning ‘ their day at the museum just as they normally do in their home in San Diego – with a ritual or coffee, meditation, and dialogue’ (Raven 1983, p. 50). They give time and attention to the process of working together, and The Lagoon Cycle tells us why this time matters and what happens. In the Seventh Lagoon the Witness recounts

Let me tell you a dream

.

I awoke knowing that the business of the universe

is conducted in an odd kind of dialogue

.

I see the Ring of Fire

as a discourse between fire and rock

taking place mainly at the water’s edge

V. “A DYNAMIC ONGOINGNESS”

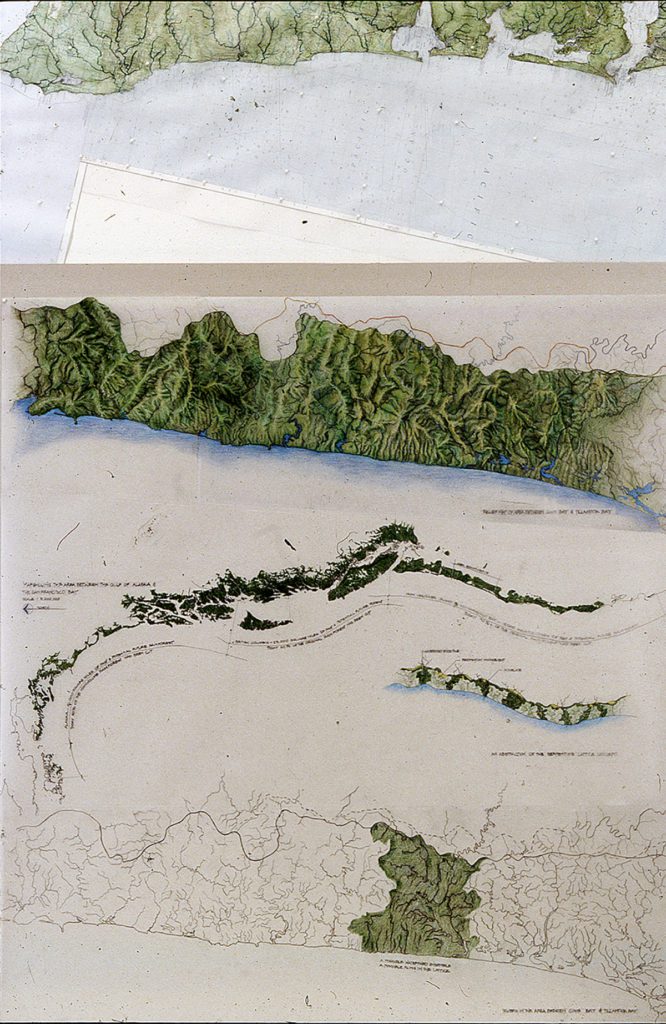

THE LAGOON MAKER RESPONDS with a series of intuitive leaps, saying three times ‘And in less than a second / I can visualize ‘, ‘ I can shrink the Pacific ‘, ‘ I can imagine / a corresponding simplification / of biocultural complexities’ (Harrison and Harrison 1985, pp. 91-92). This dream/intuition relationship of building on each other’s insights is a critical part of the reason we need to understand the Harrisons as a dynamic ongoingness, one in which empathy as a process is integral. There are indeed several instances in the works of the Harrisons where they narrate this process of intuitive building on each other’s insights. It is at the heart of The Serpentine Lattice (1993) (Figure 5) in the discussion of the two forms– the serpentine form and the lattice form and the truths embodied in both. It is in Casting a Green Net (1998), a work in which David Haley was their project manager, where they ask in the same intuitive leap ‘Can we be seeing a Dragon?’

The Serpentine Lattice, Helen Mayer and Newton Harrison, 1993.

Casting a Green Net, Helen Mayer and Newton Harrison, 1998

VI. “THE FORM DETERMINANT”

HELEN AND NEWTON PERFORMED their works, both as a way to start discussions at the beginning of projects, during projects and as part of the exhibition of projects. During these performances they frequently had disagreements. In fact, the disagreements might have been part of the performance, or from time-to-time indicative of more serious arguments. By reflecting multiple voices, they keep contradictions alive and present, often with humor and a sense of irony. One example of this can be found in Casting a Green Net in one of the sections entitled ‘ and stories were told’. This starts

He was a forester. He said wilderness areas had to come into being by themselves or not at all and he was against the manipulation of things. We asked if with that laissez-faire view, he was an optimist or a pessimist. He said that he was just a fatalist. (Harrison and Harrison, 1998, np)

In this handling, conflict and contradiction becomes a generative force and a place from which to move forward rather than a battle to be won or lost.

We began with the Harrisons’ concept of ‘the form determinant’, a set of environmental conditions that we are unable to change or control. The Harrisons have responded to these constraints imagining life itself as a process of co-creation, a process of continuously building points of similarity where there are apparently none, a process of improvisation in which constraints become generative. This is how they understand empathy and their poetics of practice unfolds through this understanding. In the Seventh Lagoon of The Lagoon Cycle they juxtapose this view of life with ‘the business of today’ that

does not encourage continuous empathy

not spaciousness of mind

Rather the business of today

encourages replacement

and change

It is conducted as a technological monologue

spoken so rapidly

that the consequences of an improvisation

most times

cannot be seen

(Harrison and Harrison 1985, p 93)

The tractor replaces the water buffalo in Sri Lanka, disturbing the ecosystem in ways that necessitate the increased use of pesticides. The water buffalo and its co-dependents were in dialogue with the land, the tractor is not. As The Lagoon Cycle comes to a close, the land and the ocean begin to speak back and the implications of temperature rise on sea levels, of garbage in the ocean confronts us as humans with the question of who and what becomes responsible in the change – who will feed whom? Who will house whom? The Harrisons map the consequences globally of land becoming uninhabitable as the sea encroaches.

This is a political issue, one that demands a plurality of perspectives and imaginations to recover our humanity and agency in the light of the overwhelming challenge of environmental devastation. By developing a practice built on empathic dialogue and exchange that is responsive to real situations, the Harrisons forge a pathway that is unusual in its clarity of purpose and transparency, one from which we can learn to judge the cost of our current ways of being.

WRITERS’ NOTE:

An earlier version of this piece was published by way of an obituary for Helen Mayer Harrison on ecoartscotland in 2018. In that writing David Haley provided the final word,

I hear the warmth of her words

the passionate chill of her poetry

such fearless insight

such good fun

such a pleasure

such grace

(Haley 2018)

REFERENCES

Fremantle, Chris and Douglas, Anne, 2016. Inconsistency and contradiction: lessons in improvisation in the work of Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison. In: J. Brady, ed. Elemental: An Arts and Ecology Reader. Manchester: Gaia Projects.

Fremantle, Chris and Douglas, Anne, 2022. Figure Ground Reversal: The Ecological Epistemology of Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison in Eds. Diana Villanueva-Romero, Lorraine Kerslake, and Carmen Flys-Junquera. Imaginative Ecologies: Inspiring Change through the Humanities. Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill. pp 81-106

Haley, David, 2018. Helen. Unpublished.

Harrison, Helen Mayer, and Newton Harrison,

- The Lagoon Cycle. Ithaca, NY: Herbert F Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University.

- Casting a Green Net: Can It Be We are Seeing a Dragon? Catalogue for Artranspennine98. San Diego: The Harrison Studio.

- Seventh Lagoon: The Ring of Water. Structure and Dynamics: EJournal of Anthropological and Related Sciences. Available from: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/45z287n2#main [Accessed 1 Jun 2018].

- Greenhouse Britain: Losing Ground, Gaining Wisdom [published proposal]. Santa Cruz: The Harrison Studio

- In The Time of the Force Majeure: After 45 Years Counterforce Is on the Horizon? Munich, London, New York: Prestel.

Harrison, Newton, 2022. The Deep Wealth Conversation [interview with Colin Campbell]. 14 June 2022. Available from: https://www.thebarnarts.co.uk/artist/newton-harrison [Accessed 22 Jul 2022].

Raven, Arlene. 1983. At Home. Long Beach, California: Long Beach Museum of Art.

Rothenberg, Jerome, 1994. Ethnopoetics at the Millennium. Available from: http://www.ubu.com/ethno/discourses/rothenberg_millennium.html [Accessed 26 Mar 2018].

Stein, Edith, 1989. On the Problem of Empathy. 3rd rev. ed. Translated by Waltraut Stein. Washington, D.C: ICS Publications.

ENDNOTES

- http://davidhaley.uk/

- We further discuss the Harrisons’ use of inconsistency and contradiction in an essay of that title (Douglas and Fremantle 2016).

List of Figures: All courtesy of the artist

Figure 1 Helen Mayer (1927-2018) and Newton Harrison (1932-2022)

Figure 2: Helen Mayer and Newton Harrison Greenhouse Britain 2006-9

Figure 3: Helen Mayer and Newton Harrison. The Lagoon Cycle 1985

Figure 4: Helen Mayer and Newton Harrison. Work Place. 1983.

Figure 5: Helen Mayer and Newton Harrison. The Serpentine Lattice. 1993.

Figure 6: Helen Mayer and Newton Harrison. Casting a Green Net. 1998

WEAD MAGAZINE ISSUE No. 13, THE ART OF EMPATHY

Published November 2022